Episode Transcript

[SPEAKER_00]: Welcome to the Core AM5 Pearls podcast, bringing you high-yield evidence-based pearls.

[SPEAKER_00]: I'm Dr.

Marty Freed, a general internist and addiction doc at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

[SPEAKER_00]: Today we're back with hyperquagibility, hard to, the clock, Dickens.

[SPEAKER_04]: That's right.

[SPEAKER_04]: We're back.

[SPEAKER_04]: With even more plot-related nuance and questionable puns.

[SPEAKER_04]: Hey.

[SPEAKER_04]: I'm Sam, a he-monkin palliative fellow at the Beth Israel-Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Math.

[SPEAKER_04]: In our last episode, we focused on hyperquigal ability testing.

[SPEAKER_04]: A rather, lots of reasons not to test, along with a few reasons to maybe test.

[SPEAKER_00]: But this time, we're going to get our hands dirty.

[SPEAKER_00]: We're focusing on management today, and we're not alone.

[SPEAKER_00]: In just like last episode, we're joined by Dr.

Rebecca Carpleef, and Dr.

Jean Connors, hail from some incredible institutions around Boston.

[SPEAKER_03]: So hi, everybody.

[SPEAKER_03]: My name is Rebecca Carplief, and I'm a classical hematologist.

[SPEAKER_03]: I am on staff at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

[SPEAKER_02]: I'm Jean Connors.

[SPEAKER_02]: I'm a hematologist and adult hematologist at Brigham Young Women's Hospital and Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

[SPEAKER_04]: We are also joined by our very own Dr.

Ken Bauer from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

[SPEAKER_04]: If you haven't listened to hyperquigal ability part 1, listen to that first.

[SPEAKER_04]: It provides the foundation for today's episode.

[SPEAKER_04]: And once you've got that under your belt, join us for some high-ild pearls about clot management.

[SPEAKER_04]: Are we ready?

[SPEAKER_04]: Try quizzing yourself on the following pearls.

[SPEAKER_04]: Remember, the more you test yourself, the more learning you'll get out of this.

[SPEAKER_00]: Pro one, managing the higher risk-provoked clots.

[SPEAKER_00]: The provoked clots with irreversible risk factors.

[SPEAKER_04]: As a reminder from episode one, we're calling these clots provoked irreversible for short.

[SPEAKER_04]: So, how long do we anti-quagulate for these?

[SPEAKER_04]: Are we really treating them like unprovoked clots?

[SPEAKER_04]: indefinitely?

[SPEAKER_04]: Can we ever de-escalate therapy?

[SPEAKER_00]: Pro two, managing provoked reversible clots.

[SPEAKER_04]: These clots have a lower risk for recurrence, so we usually treat these short term, but when and how do you decide to stop?

[SPEAKER_00]: Pearl 3.

[SPEAKER_00]: Antequaguant failure When do we step it up?

[SPEAKER_00]: And Pearl 4.

[SPEAKER_00]: The antifospholipid antibody syndrome.

[SPEAKER_04]: The wild card.

[SPEAKER_04]: The exception to everything we've talked about so far.

[SPEAKER_04]: This is a do not misdiagnosis.

[SPEAKER_04]: And that's it for the episode.

[SPEAKER_00]: Now, usually our episodes have five pearls.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's the name of the segment, you know?

[SPEAKER_00]: But these are pretty hefty pearls we've got here and we're covering quite a bit of ground with just the four.

[SPEAKER_04]: You won't miss that last pearl, promise.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, let's dive in.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's clot-busting time.

[SPEAKER_04]: You'd think, but the devil's in the details, how long do we treat?

[SPEAKER_04]: What dose?

[SPEAKER_04]: What else do we think about?

[SPEAKER_00]: So the traditional teaching is three to six months of anti-quagulation therapy for a quantum quote, provoked clot.

[SPEAKER_00]: And then we talk about indefinite anti-quagulation for a quantum quote, unprovoked clot.

[SPEAKER_04]: But it's not as simple as provoked or unprovoked, is it?

[SPEAKER_04]: Quick throwback to episode one, whenever you see a provoked clot, think to yourself, [SPEAKER_00]: So a provoked reversible risk factor like after surgery is generally treated short-term.

[SPEAKER_00]: A provoked but irreversible risk factor, let's say an inturable cancer, or that Crohn is probably not going to go away for most people.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's often treated like an unprovoked clot, we treat this with long-term anti-quagulation.

[SPEAKER_04]: But still, it's not so simple.

[SPEAKER_04]: Even with this framework, theoretically, you'd treat unprovoked and provoked irreversible clots the same, with lifelong anticoagulation.

[SPEAKER_04]: But in practice, we don't always do that, so the question is, why not?

[SPEAKER_00]: To get to the bottom of it, let's walk through a couple cases.

[SPEAKER_04]: Totally.

[SPEAKER_04]: We're going to talk through three cases, which, by the book, could all be managed the same way, but they won't be.

[SPEAKER_04]: Let's start with the softball case, the classic.

[SPEAKER_04]: You've got a 60-year-old woman with metastatic pancreatic cancer on palliative chemotherapy, and she develops a clot in her superior mesenteric vein.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, this is totally not reversible.

[SPEAKER_00]: Her cancer is the provoking factor, and unfortunately for this person, the risk factor is probably never going to go away.

[SPEAKER_00]: So she's on life on anticoagulation for sure.

[SPEAKER_04]: Roger that.

[SPEAKER_04]: And by the way, do Axe were just fine in cancer-associated clots, even though in Oxuparen was the prior standard of care.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, that wasn't so bad.

[SPEAKER_00]: Let's move on to case two.

[SPEAKER_04]: Yeah, let's try the other end of the spectrum.

[SPEAKER_04]: Let's say she's still 60, but this time, no cancer history, totally healthy.

[SPEAKER_04]: She gets a calf DVT on a three-hour plane ride.

[SPEAKER_00]: Ooh, okay, this is a throwback to episode one.

[SPEAKER_00]: I got this.

[SPEAKER_00]: We learned that the data for travel associated VTE is stronger after five to six hours of travel.

[SPEAKER_00]: So three hours just isn't enough to provoke a cloud.

[SPEAKER_00]: So she's really in that unprovoked category.

[SPEAKER_04]: But at the same time, it doesn't really feel like we should treat her like unprovoked.

[SPEAKER_00]: Right, so for this little distal plot, I really don't want to be anti-quagling this person forever.

[SPEAKER_04]: How risky would it be to not anticoagulate forever?

[SPEAKER_04]: What's her risk of recurrence?

[SPEAKER_01]: There is pretty solid data that are current risk.

[SPEAKER_01]: After, let's say an unprovoked, proximal EVT is, you know, plus or minus 10% in the first year and 25% in four years and 35%, 40% out to 10 years, if you will, the risk of a distilled EVT is half of that.

[SPEAKER_04]: So basically, a distal clot, aka clot below the knee, has half the recurrence risk of a proximal clot.

[SPEAKER_04]: That does make me feel a little better.

[SPEAKER_04]: And if we follow Dr.

Bauer's numbers here in one year, 5% of people might have a recurrence of their calf DVT, but it's also a calf DVT.

[SPEAKER_00]: And I guess that invalidates my instincts actually, it sounds like the takeaway here is for unprovoked clots that are clinically low-risk, like the dislocation here, it's probably very reasonable to anticoagulate just for the short term.

[SPEAKER_04]: Totally.

[SPEAKER_04]: And right here, you see the discrepancy, right?

[SPEAKER_04]: Case one, our patient with cancer, is provoked irreversible and is treated for the rest of her life.

[SPEAKER_04]: Case 2, distilled DVT after a little plane time, is unprovoked, but is treated short-term.

[SPEAKER_04]: And why are these two treated differently?

[SPEAKER_04]: The devil's in the details, right?

[SPEAKER_04]: It all depends on two risks.

[SPEAKER_04]: Number 1, how clinically risky the cloud itself is, and number 2, the recurrence risk.

[SPEAKER_04]: And as we've just heard, the data shows us that a distilled DVT just isn't as risky in either sense.

[SPEAKER_00]: So when we're thinking about clinical risk assessment, mostly we're looking at where that clot is and how much of it we're talking about.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's right.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, so let's use that risky risk framework in the third case.

[SPEAKER_04]: All right, third case, let's go.

[SPEAKER_04]: Let's say she's still 60.

[SPEAKER_04]: This time, she doesn't have cancer.

[SPEAKER_04]: She's actually immobilized after a spinal cord injury.

[SPEAKER_04]: and...

[SPEAKER_00]: Direct forever.

[SPEAKER_04]: Well, hold on a second here.

[SPEAKER_04]: I wasn't done yet.

[SPEAKER_04]: And let's say she's got a little chronic GI bleeding.

[SPEAKER_04]: Some AVM's no one's been able to zap maybe.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, so...

[SPEAKER_00]: This one you got me a little bit.

[SPEAKER_00]: I no longer want to direct forever.

[SPEAKER_00]: I'm legitimately stuck.

[SPEAKER_00]: You either continue the blood thinner or you don't.

[SPEAKER_00]: It seems like those are my two options.

[SPEAKER_04]: What if we said there was a middle ground?

[SPEAKER_00]: Wait a minute, but how anti-cargulation is sort of a binary thing, either are anti-cargulated or you're not?

[SPEAKER_04]: So, there's a secret third option, half dose, indefinite dough act.

[SPEAKER_00]: Wait a minute.

[SPEAKER_00]: Is this like a-fib?

[SPEAKER_00]: Because in a-fib, we know we can use dose-reduced a-pix-a-band if your patient has two of the three following categories, you know, age older than 80 years, weight less than 60 kilograms, or a creatinine of greater than equal to 1.5.

[SPEAKER_04]: Well, that's true, but the situation is a little different, because you're still giving your patients the initial three to six months of full dose treatment for VTE.

[SPEAKER_04]: But then, after, you can dose reduce your doughach for secondary VTE prophylaxis.

[SPEAKER_00]: Ooh, okay into a sauntay.

[SPEAKER_00]: Tell me a little bit more about this dose-reduce trickery.

[SPEAKER_04]: This is thanks to two international randomized clinical trials.

[SPEAKER_04]: These trials both looked at what you do after you complete initial clot treatment.

[SPEAKER_04]: Amplify Extend, the first trial, looked at continuing Lodos of Pixivan, 2.5 BID.

[SPEAKER_04]: And Einstein Choice, the other trial, did the same thing with Lodos Riveroxaban, 10 milligrams daily.

[SPEAKER_04]: And both these trials found that the half-Jose Blut thinner did just as well at reducing clot recurrence as full-dose Blut thinner long-term.

[SPEAKER_03]: There was a slight reduction in bleeding risk in the patients who are on the 2.5 versus the 5 milligrams BID.

[SPEAKER_03]: And actually the rate of bleeding on the 2.5 milligrams BID was actually about equivalent to placebo in this study.

[SPEAKER_03]: Sort of implying that, you know, a piece of M2.5 milligrams BID really is a safe drug from a bleeding risk perspective.

[SPEAKER_04]: Wow, that's really something.

[SPEAKER_04]: To see that the bleeding risk of a half-dose blood dinner is not significantly different from placebo, kind of great news.

[SPEAKER_04]: And it's helpful that amplify extend look to the broad set of patients.

[SPEAKER_04]: Basically, the folks who had sticky situations where you could make a good argument to either continue or stop anticoagulation.

[SPEAKER_00]: And our case certainly is one of those, right?

[SPEAKER_00]: We have a six-year-old woman with a provoked, but non-modifiable DVT.

[SPEAKER_00]: So, on one hand, we'd want to anti-quagulate indefinitely.

[SPEAKER_00]: But, on the other hand, she's a bleeder, so we could argue to stop after a short course of anti-quagulation.

[SPEAKER_00]: Totally.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, mind is officially blown.

[SPEAKER_00]: I am curious though, how does a hematologist apply this in practice?

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, even if the trials included a broad selection of patients, who should we be thinking about for those reduced candidates?

[SPEAKER_03]: I don't know that one size sort of shits all for patients.

[SPEAKER_03]: If someone is young, they have normal kidney function, normal liver function, they're doing well, they had a large clot.

[SPEAKER_03]: I typically will keep them on full-dose anticoagulation if somebody had a clot that wasn't completely a new pathic work, especially if they're older, we do know that older patients metabolize the dox to this rapidly, it clears less rapidly than patients who are younger.

[SPEAKER_03]: I have a very low threshold to reduce the dose.

[SPEAKER_04]: One gap in these two trials is neither of them had very many cancer patients.

[SPEAKER_04]: So initially, we didn't know if this strategy applied safely to the malignancy population.

[SPEAKER_04]: But good thing that just changed, there was a trial published this March, the Ape Cat trial, which looked specifically at patients with active cancer.

[SPEAKER_04]: And just like Amplify Extend and Einstein's choice, this Ape Cat found dose-reduced a [SPEAKER_04]: It also found a reduction in its composite bleeding outcome compared to the full dose.

[SPEAKER_00]: So we can use this strategy in cancer patients.

[SPEAKER_00]: That is definitely good to know.

[SPEAKER_00]: I still am probably going to be asking hematologist for help.

[SPEAKER_00]: But for now, it really does seem like these trials give us a reason to think about dose reducing as a viable option.

[SPEAKER_04]: There's a lot of nuance in these cases, and we kind of just want you to be aware of dose reduction as an option, but just remember you're not alone in making these decisions.

[SPEAKER_00]: I do feel comforted by that warm, fuzzy blanket of a game console here.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, Sam.

[SPEAKER_00]: Let's wrap up these cases into some practical take-home points.

[SPEAKER_00]: So the duration of treatment really depends on two risk factors.

[SPEAKER_00]: How risk is the cloud itself and for that we think about size and location.

[SPEAKER_00]: And then what is the risk of recurrence of that cloud?

[SPEAKER_00]: The old risky risk framework.

[SPEAKER_00]: And we've got three options for the truly unprovoked or irreversible cloud.

[SPEAKER_00]: First, anticoagulate forever, this is the traditional teaching, and this is for really that high-risk patient, like a patient with metastatic cancer, where the risk is never going away.

[SPEAKER_00]: Option 2, we get anticoagulate short-term.

[SPEAKER_00]: This is for patients with the lowest risk clot, like distal dvTs.

[SPEAKER_00]: The risk of harm is low, and the risk of recurrence is also low.

[SPEAKER_00]: Remember that distal dvTs have half the recurrence rate of proximal ones.

[SPEAKER_00]: And finally, third option is I quietly short-term and then continue long-term dose-reduced dough act.

[SPEAKER_00]: This is for the patient clearly has a high risk of recurrent clot, but is also maybe older or has a high bleeding risk or maybe has poor kidney or liver function.

[SPEAKER_00]: Consider this one together with your local friendly hematologist.

[SPEAKER_04]: All right, now let's move on to the other bucket of clots, but clearly provoked reverse of clots.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, Sam, we're finally catching a break here.

[SPEAKER_00]: We got an easy one.

[SPEAKER_04]: Provoked reverse of all clots are kind of nice like that.

[SPEAKER_04]: Short-term anticoagulation and your done.

[SPEAKER_00]: by the boom, but the question that I have is what counts as short-term anti-coagulation?

[SPEAKER_00]: Is some people say three months?

[SPEAKER_00]: Some people say six months?

[SPEAKER_00]: Is there anyone splitting the difference here with that rare four and a half month anti-coagulation?

[SPEAKER_01]: Studies haven't really shown any different outcomes in three versus six all up and go six for a first major proximal DDT or pulmonary embolism and then decide where they need long-term therapy but some people might make that decision three as I say the evidence is three is as good as six months for that initial treatment.

[SPEAKER_00]: Hmm, kind of interesting that three months six months it doesn't seem to make a difference.

[SPEAKER_04]: I have seen some practice variation around here.

[SPEAKER_04]: I think the takeaway here is, while the evidence doesn't show much of a difference overall, some hematologists like Dr.

Bauer will prefer six months for a big clot, and three months for a smaller clot, like a distal DVT.

[SPEAKER_02]: So you might not want to stop at three months if people still have significant swelling and have not yet had clot resolution.

[SPEAKER_02]: And it's kind of interesting because remember, anti-coagulants do not dissolve clots.

[SPEAKER_02]: They prevent clot propagation.

[SPEAKER_02]: They prevent them from getting bigger.

[SPEAKER_02]: And you actually have to allow, you know, natural, [SPEAKER_04]: And that adds another layer to the logic.

[SPEAKER_04]: This is kind of why the three versus six month debate probably doesn't make a huge difference overall.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's because that high-risk period is really the initial six or so weeks where you have the highest risk of a clock propagating.

[SPEAKER_04]: And after that, it's a little bit less critical.

[SPEAKER_04]: Of course, like Dr.

Connor says, if your patients still having symptoms at three months, that's different, and I think most clinicians would not be inclined to stop at that point.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, one thing I've always wondered is how about that plain travel situation?

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, not this three hour flight, but let's say someone really got a DVT after a 12 hour flight.

[SPEAKER_00]: And now they're planning on getting on a plane again and worried about that provoking factor coming back again.

[SPEAKER_00]: I've heard people pop in a river oxaban or maybe giving themselves an inoxyparin shop before a flight if they've had a clap before, but I'm not sure that's exactly the data driven.

[SPEAKER_02]: There are no data.

[SPEAKER_02]: There will never be any data for DOX for travel prophylaxis.

[SPEAKER_02]: I harassed the people who wrote the Ash, VTE treatment guidelines when they came out in 2018 and said, guys, there's a perfect opportunity to give guidance on using DOX for air travel prophylaxis.

[SPEAKER_02]: They're like, well, we couldn't, because there's no data.

[SPEAKER_02]: I said, but you all do it.

[SPEAKER_02]: No, oh, yeah, okay.

[SPEAKER_02]: So sometimes what the data say and what we do are not congruent.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, good to know.

[SPEAKER_00]: I like to tell one of our peer reviewers put it.

[SPEAKER_00]: We're basically just negotiating what feels right to our patients.

[SPEAKER_00]: Practice is all over the place.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm not a huge believer in prophylactic lovin' ox, a single dose, sometimes the question comes up and putting them on dough ax, I sometimes say I think these are more angelitic than yellowing what I'm doing, but I have to work with patients and come up with the best solutions for them for these kind of things, especially if they're not a long-term therapy, they're really flying back to Asia or something like that, it's not our reason to prophylax them.

[SPEAKER_00]: Alright, so it sounds like there is a healthy amount of practice variation here too, good to know.

[SPEAKER_04]: Wow, that pearl really flew by.

[SPEAKER_04]: Let's summarize what we talked about.

[SPEAKER_04]: Key point here is the management of the provoked reversible clot is subject to some of that practice variation more than you'd think about duration.

[SPEAKER_04]: Studies haven't really shown a difference between three or six months of anticoagulation to start, and so that comes down to the clinician.

[SPEAKER_04]: Some hematologist might favor six months for bigger clots and three months for smaller ones.

[SPEAKER_04]: about travel.

[SPEAKER_04]: When thinking about clots provoked by travel, the idea of travel profile access often comes up.

[SPEAKER_04]: And there's huge variation here, too, in the absence of any data to guide it.

[SPEAKER_04]: Some hematologists really don't support it, while others leave it open to a risk-benefit conversation with their patients.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, everyone.

[SPEAKER_00]: We've covered a lot of ground, and there are lots of therapeutic approaches.

[SPEAKER_00]: Let's move on to what happens next when anticoagulants fail.

[SPEAKER_04]: Oh, yes, the dreaded doughach failure.

[SPEAKER_04]: Join us in the next pro for a shout about it, as well as some assorted tips and tricks.

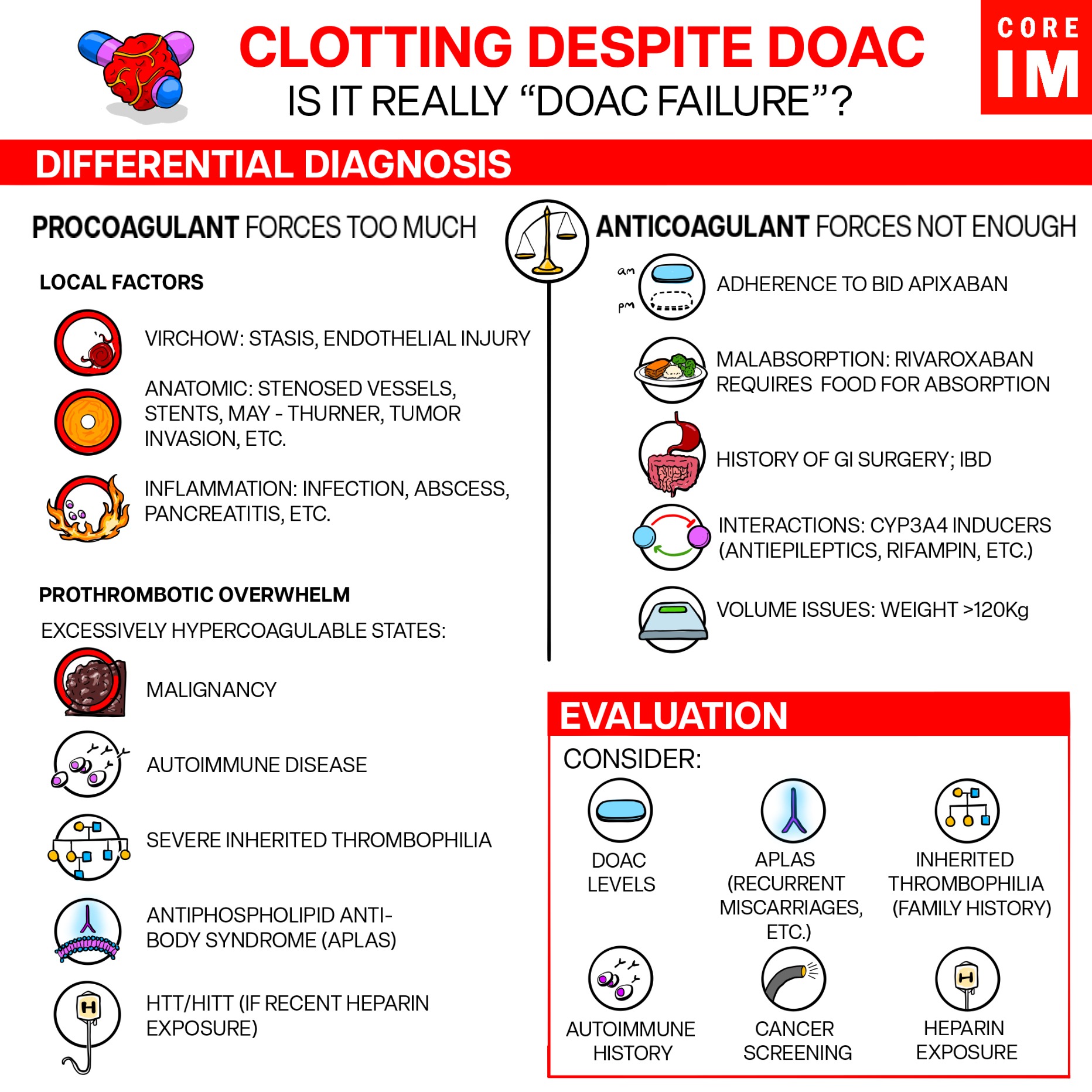

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, so here we're talking about anti-coigulation failure.

[SPEAKER_04]: Yeah, let's get into it.

[SPEAKER_04]: I feel like we're usually talking about doughach failure.

[SPEAKER_04]: You know, lovely 80-year-old on a Pixivan is another calf dbt.

[SPEAKER_04]: And you were really trying not to escalate in meaning?

[SPEAKER_03]: So, really, underlying risk factor, why did that cloud happen?

[SPEAKER_03]: The most common situation in which ICM, techawagulate failure is really in widespread malignancy, especially in solid tumors that are responding to treatment.

[SPEAKER_03]: It's really our frontline treatment now for patients with malignancy associated with rembosis, and we're all using them.

[SPEAKER_03]: It's not that a big suban is a bad drug, or a rock suban is a bad drug.

[SPEAKER_03]: It's just we can't control these tremendous production of tissue facts are, [SPEAKER_04]: Thinking about Verkau's triad again, the cancer could also cause direct endothelial injury, or stasis if blood flow is blocked by tumor.

[SPEAKER_04]: Anticoagulants aren't really going to do anything about that mechanical risk for clot.

[SPEAKER_04]: You can throw all the doughaxe you want at that, but thinning the blood is not going to completely get rid of that clot risk.

[SPEAKER_00]: So it's not a doughaxe failure per se, but either way, what do you do?

[SPEAKER_03]: If they're on a direct oral anticoagulant, I typically will switch them to low molecular weight haprine.

[SPEAKER_03]: We do know that haprine drugs you have some anti-inflammatory effect as well.

[SPEAKER_04]: Right, so if someone's clotting through a doughach, we switch to a different mechanism of blood thinning.

[SPEAKER_04]: Maybe one that has a little anti-inflammatory effect like the haprines.

[SPEAKER_04]: So working up recurrent clot, I always make sure people are up to date on their cancer screenings.

[SPEAKER_04]: But what else do the experts consider?

[SPEAKER_03]: at check patients for anti-fastful of the antibodies, so if somebody's doing, if somebody has a PE and they're on a doughnut, you want to make sure that you're ruling out anti-fastful of the antibodies in general, because again, that's one of those conditions where we really don't want to use the direct or early anti-clreds.

[SPEAKER_00]: Ah, yes.

[SPEAKER_00]: The anti-fossil lipid antibody syndrome or APLIS.

[SPEAKER_00]: We're going to get into that with our next pearl.

[SPEAKER_00]: But for now, we'll say that APLIS is rare.

[SPEAKER_00]: Not everyone who clots through a DOEC needs anti-fossil lipid antibody testing.

[SPEAKER_00]: But it's a good thing to keep on your differential.

[SPEAKER_00]: Is the reason your patients clotting through a DOEC is because they may have APLIS, and they need warfring instead.

[SPEAKER_04]: Whether it's APLAS or not, whenever I get one of these consults for DoAq failure, sometimes I find the location of the clot can be a big clue.

[SPEAKER_04]: One of the things that points me to think about an underlying issue is specifically Splanknik thrombosis, meaning clots in the Splankniks, the portal vein, or mesenteric veins.

[SPEAKER_04]: These are kind of yellow flags to me.

[SPEAKER_04]: I think of things like gastric bypass surgeries, GI cancers, cirrhosis, hemalignancies, other [SPEAKER_01]: It is a feature, particularly of the mile of proliferate disorders to develop either budciari, which is, you know, the paddock deans from boces or portal deans from boces, as well as, I mentioned the mile of proliferate disorders, as well as a rare hemologic disorder, P&H, but it can be seen even with a dominal surgery.

[SPEAKER_00]: So basically, if you see a weird clot location, we should think about surgeries as solid tumor in the region or some weird hematologic thing.

[SPEAKER_00]: Probably not a bad idea to get a hematologist involved at that point regardless.

[SPEAKER_04]: Thinking again about our differential for doughach failure, I always like to make sure, was it really failure to begin with?

[SPEAKER_03]: They have given Riverox bin the benefit of the doubt patients really have to take it with food.

[SPEAKER_03]: There was a small study showing that it is absorbed in the stomach and that there's better absorption with food so let's say somebody was taking it every morning, that eating breakfast and then they had distilled DVT else they were, they weren't taking it appropriately.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's always on my list to ask patients if they're taking their river rocks to bandwidth food.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's on the package and start to take it with dinner and why is that?

[SPEAKER_04]: Because it's usually people's biggest meal with the highest fat content, meaning the most absorption.

[SPEAKER_03]: Of course, Cliff, we're a friend.

[SPEAKER_03]: You want to make sure that Ariana is actually therapeutic and that they have good.

[SPEAKER_03]: It's called time in therapeutic range, which means, what is the percentage of time that their INR is between two and three or whatever your range is?

[SPEAKER_04]: So, if we see an INR time and range is, say, less than 60%, we start thinking, that might be the issue.

[SPEAKER_00]: Let's say we've confirmed that they were taking their meds, and our patients were taking them appropriately.

[SPEAKER_00]: How do humans all just decide about switching anti-quagulation therapy versus stay in the course?

[SPEAKER_03]: I think it's sort of a risk benefit with the patient.

[SPEAKER_03]: How big was the clot?

[SPEAKER_03]: How long were they off of anticoagulation for?

[SPEAKER_03]: How severe was their infection or inflammatory response that you're saying was the ideology of the failure?

[SPEAKER_03]: If it's a small clot and there's a good compelling reason why somebody may have clotted despite anticoagulation, then the patient is willing to take the risk to remain on a direct oral anticoagulant because there's so much more convenient.

[SPEAKER_03]: Then we'll have a good sort of risk benefit conversation.

[SPEAKER_04]: So, it comes down to our provoked unprovoked discussion again.

[SPEAKER_04]: Is that risk factor for the recurrent clot reversible?

[SPEAKER_04]: If so, maybe we stay with the current drug.

[SPEAKER_00]: Now, something we really toyed about whether to include in this episode or not was repeat labs or imaging to help with that question of DOAC failure.

[SPEAKER_03]: And I use D-Dimer as day-thines and to help me figure out if somebody has new clots, that's actually the same way I use repeat ultrasound.

[SPEAKER_04]: So that's pretty cool.

[SPEAKER_04]: We often think of D-Dimer as these much maligned tests were never supposed to order them.

[SPEAKER_04]: But, you'll occasionally see a hematologist order a D-Dimer, and this is one reason why, to see if the clot burden is increasing.

[SPEAKER_04]: If that D-Dimer is rising, it might actually push us to consider another anticoagulant.

[SPEAKER_00]: Right, and we should say this isn't exactly an evidence-based approach.

[SPEAKER_00]: The American Society of Humanity Guidelines suggest against using D-divers, and for that matter, it also suggests against using repeat imaging and prognostic scores to guide into a coagulation duration.

[SPEAKER_04]: But in the fine print, it does say, in the right circumstances, if there's uncertainty, I have seen the D-Dimer be used as one piece of information that helps guide us one way or the other.

[SPEAKER_04]: And again, it's all about trying to get a sense of whether the amount of clot is increasing or not with your current anti-quakeelation strategy.

[SPEAKER_00]: And with that, we'll wrap up our final pearl with the quick summary.

[SPEAKER_00]: First of all, confirm it's actually a dough-act failure.

[SPEAKER_00]: Riveroxid man is going to be a problem for your patients who skip meals or maybe our NPO for other reasons.

[SPEAKER_00]: The core message here is you really want to work up anti-coragulation failure like you would with any other clot.

[SPEAKER_00]: Do they have an underlying provoking risk factor that isn't being addressed?

[SPEAKER_00]: Don't forget about cancers, or APLS with recurrent clots.

[SPEAKER_00]: Do they have clots in weird bascular beds that can be a clue about hematologic malignancies, or solid tumors, or prior surgeries causing issues.

[SPEAKER_00]: For example, gastric bypass has that classic association with splankmic thrombus.

[SPEAKER_04]: Now, it's time for Pearl 4.

[SPEAKER_04]: We promise to talk about it so here it is.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's APLS time.

[SPEAKER_00]: So, the anti-fossil lipid antibody syndrome, the elephant lurking in the room, that's right.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's APLAS.

[SPEAKER_04]: I think we're all afraid of missing this one.

[SPEAKER_03]: Anti-fossil lipid antibody syndrome is own unique beast.

[SPEAKER_03]: Patients can have a risk as high as 40% of recurring clad at over 10 years.

[SPEAKER_00]: Wow, that is a very high recurrence risk.

[SPEAKER_00]: And let's remember, these are some pretty morbid clots too.

[SPEAKER_00]: Strokes and other arterial clots which can be really life-limiting.

[SPEAKER_04]: To suspect APLAS, your patient needs to meet clinical criteria first.

[SPEAKER_04]: That said, these are pretty broad.

[SPEAKER_04]: Basically, any unexplained clot could count.

[SPEAKER_04]: That could be in a stroke, an MI, pregnancy outcomes like pre-eclampsia with severe features, even, or any pregnancy loss before 34 weeks.

[SPEAKER_00]: And let's just paint the picture.

[SPEAKER_00]: APLS doesn't follow any of the rules we've talked about so far.

[SPEAKER_04]: Here are some examples of the way APLS can present.

[SPEAKER_04]: I've actually seen a couple of these.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's pretty humbling.

[SPEAKER_04]: For example, the patient with the unexplained arterio-clot, say acute mesenteric ischemia in a 20-year-old without any risk factors, no embalic source.

[SPEAKER_04]: Maybe it's a young person with a stroke under age 50, or numerous miscarriages.

[SPEAKER_04]: I've seen a teenage patient permanently bedbound due to recurrence strokes despite anti-quagulation.

[SPEAKER_04]: Might even be a high burden or recurrent VTE, like an extensive or saddle PE and a young patient with no risk factors, or an extensive clot recurrence in a patient who's already on a doughach.

[SPEAKER_00]: That is a pretty sobering list.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's a good reminder, APLS is a bad actor.

[SPEAKER_04]: One tiny little clue, and it's by no means perfect.

[SPEAKER_04]: If I see someone coming in with a suspicious picture and even before starting them on anticoagulation, their PTT is elevated, even just a little bit, I think, you know, that's odd.

[SPEAKER_04]: And it might just push me towards sending APLA S testing.

[SPEAKER_00]: And if your spotty senses go up with any of those in a patient's history, you really should test for it.

[SPEAKER_00]: Unlike the take home of episode one, that was testing rarely changes your management, APLAS is the exception.

[SPEAKER_00]: Testing will definitely affect your anti-quickly strategy, he can follow up and counseling.

[SPEAKER_00]: Honestly, Sam, I think it makes sense to do a quick refresher on APLS testing itself.

[SPEAKER_04]: Totally.

[SPEAKER_04]: There are three big tests we think about.

[SPEAKER_04]: Anti-cardiolipin, beta-tugalicoprotein antibodies, and the Lupus Anticoagulant.

[SPEAKER_04]: Big picture?

[SPEAKER_04]: These are all tests for antibodies against different types of phospholipids, which make up our cell membranes.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, shoot!

[SPEAKER_00]: I was today years old when I learned that you'd test with the anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome by looking for antibodies against phospholipids.

[SPEAKER_04]: Yeah, it's funny how that works.

[SPEAKER_04]: Now, phospholipids are everywhere in our circulatory system, and in particular, they're all over platelets, so antibodies against phospholipids can lead to platelet activation in clot.

[SPEAKER_04]: Of these three tests, anti-cardiolipin and beta-2 glycoprotein are two very specific antibodies we can test for directly.

[SPEAKER_04]: And for these, we test for both the IGG and the IGM form.

[SPEAKER_04]: Doesn't really matter to us because both of them lead to clots.

[SPEAKER_04]: One important and really common confusion point here is that it's easy to confuse beta to glycoprotein and beta to microglobulin.

[SPEAKER_04]: They sound very similar, but are two totally different things.

[SPEAKER_04]: Antibata to glycoprotein is the APLAS antibody, beta to microglobulin is a prognostic marker in my aloma.

[SPEAKER_04]: And we sometimes see people accidentally ordering a beta to microglobulin when they need to order a beta to glycoprote an antibody.

[SPEAKER_04]: And props for trying to diagnose this, but remember, with microglobulin, the M is for myeloma.

[SPEAKER_00]: Alright, so, anti-cardiolipin and beta to glycoprotein are the two antibodies.

[SPEAKER_00]: What's the third test?

[SPEAKER_04]: The last is the so-called lupus anticoagulant.

[SPEAKER_04]: And that one's actually not a specific antibody.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's referring to a whole group of antibodies that finds it phospholipids, and we collectively call them the lupus anticoagulant.

[SPEAKER_00]: Hmm.

[SPEAKER_00]: Why lupus?

[SPEAKER_04]: Patients with lupus are at an increased risk of APLAS, but don't let the name fool you.

[SPEAKER_04]: There are plenty of APLAS patients who don't have lupus, so it's really not that great of a name.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, but why the lupus anti-quagulent?

[SPEAKER_04]: Because this group of anti-phospholipid antibodies will bind up all the phospholipids in your clotting assay, which prolongs the PTT and makes it look like an anti-quagulent.

[SPEAKER_04]: The irony is, these antibodies are actually pro-quagulent.

[SPEAKER_04]: That's the whole problem.

[SPEAKER_00]: Geez, that's a bit misleading.

[SPEAKER_00]: We're calling it the lupus anti-quagulent.

[SPEAKER_00]: Maybe it really should be the lupus pro-quagulent.

[SPEAKER_04]: hematologists have been mad about the so-called lupus anticoagulant for a while now.

[SPEAKER_04]: One of our peer reviewers actually calls it the worst name thing in all of medicine.

[SPEAKER_04]: Anyway, don't be fooled by anticoagulant in the name or the long PTT.

[SPEAKER_04]: These patients clot.

[SPEAKER_00]: Man, so last episode we talked about the hyperquagulability tests and which ones are affected by blood thinners.

[SPEAKER_00]: What if this patient is the ED and was already started on a hepper injury?

[SPEAKER_00]: Can you still send off all three of those tests?

[SPEAKER_04]: The only one that is impacted by being on blood thinners is the lupus anticoagulant.

[SPEAKER_04]: The test just works differently because it's a test for a whole group of antibodies.

[SPEAKER_04]: You might ask why, and it's kind of a long story, but the punchline is that it's a less direct test.

[SPEAKER_04]: And when you're on blood thinners, you can't really trust the result.

[SPEAKER_00]: But at least I can send those two antibody tests, right?

[SPEAKER_00]: And if they're positive, they probably have a epilias.

[SPEAKER_04]: Sadly, it's not that simple.

[SPEAKER_04]: The anti-cardiolite bin and the anti-Batitude leg protein tests have a pretty high false positive rate, so you have to repeat them 12 weeks later to confirm that they're still present, to confirm a diagnosis of APLAS.

[SPEAKER_00]: Jeez.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's a tough three months while you're waiting to see if those anti-fossilipid antibodies are false positives or not.

[SPEAKER_02]: Exactly.

[SPEAKER_02]: The presence of an anti-fossil lipid antibody does not mean that someone has anti-fossil lipids syndrome, okay, and so if you walk [SPEAKER_02]: 5% to 10% of healthy blood donors walking around have the presence of an anti-fossilipid antibody.

[SPEAKER_02]: They have never had a clot in the vast majority or never going to go on to develop a clot.

[SPEAKER_02]: If you look at children and even teenagers and college students who get strep throat, they will have a positive anti-carry lipid antibody that prolongs their PTT, but they do not usually develop thrombosis.

[SPEAKER_00]: All right, that sure complicates things, so even 12 weeks out, the antibodies aren't cut and dry.

[SPEAKER_04]: And that's sort of why this is a spectrum of risk, and the number of positive test matters.

[SPEAKER_04]: Patients with all three tests being positive and confirmed 12 weeks later are in a whole different bucket of risk for clots.

[SPEAKER_04]: We call these patients triple positive.

[SPEAKER_01]: the dough acts in people who turn out to be triple positive are inferior to warfriend therapy.

[SPEAKER_01]: So it has an implication both on long-term anti-quagination decisions as well as the issue of potentially what anti-quagant you should use if you're triple positive.

[SPEAKER_04]: Driving at home, the scary APLAS cases tend to be the triple positive ones.

[SPEAKER_02]: We kind of want to identify up front, someone who might be triple positive, and those are usually younger patients that come in with an arterial event that worry me the most.

[SPEAKER_02]: And even some older patients who don't have any of the traditional risk factors for stroke from body stroke, they don't have bad hypertension, dyslipidemia, [SPEAKER_02]: diabetes and obesity and smoking.

[SPEAKER_02]: So if they're none of those things and they come in with a stroke and they don't have, you know, crowded, after all, sclerosis and they don't have anything else, I do think in many of those patients it's worth checking to see if they're triple positive.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, I'm getting the triple positive folks are the ones who tend to be more severely affected, but what if you aren't triple positive?

[SPEAKER_00]: Say it's just one or two antibodies.

[SPEAKER_02]: We don't know whether or not we could safely give a do act to patients that are single positive or double positive.

[SPEAKER_02]: There was a much smaller study done with re-rexban in the United Kingdom of a hundred patients.

[SPEAKER_02]: None of them were triple positive.

[SPEAKER_02]: Most of them were single, persistently positive.

[SPEAKER_02]: They had no recurrent DTE events after a year.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, so maybe we can get away with do act in the single positive folks.

[SPEAKER_01]: And we'll also add that the arterial group are the ones that particularly did badly on a doughach more so than the people with BTE.

[SPEAKER_01]: So on these again, we're the triple positive.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think in general, people have become very cautious, even in single-positive APLS, about periphery.

[SPEAKER_01]: And certainly, if they are of arterial events.

[SPEAKER_04]: The number of antibodies really matters, as does the clinical picture.

[SPEAKER_04]: Triple positive means warfare in for sure.

[SPEAKER_04]: Single or double positive?

[SPEAKER_04]: It's harder to say, though I think a lot of people will play it safe.

[SPEAKER_04]: And, reminder, this does require confirmation 12 weeks later.

[SPEAKER_00]: And I guess that begs the question, what do we do in the meantime?

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, salmon bidding this patient, I'm thinking about APLIS and sending the antibodies, but we know the antibodies aren't gonna come back for a couple days, so do I start wherfering like ASAP, just in case?

[SPEAKER_04]: Really, that's in the hematologist's hands.

[SPEAKER_04]: Generally speaking, in a high risk clot, like a bad stroke, or if you find out your patient's triple positive, wherfering is probably the move, [SPEAKER_04]: On the other hand, if it's a lower risk cloud and there are maybe one or two lower tighter antibodies, they may not need Warfarin right away.

[SPEAKER_04]: The upside is you generally have a second to think here and call on your friends.

[SPEAKER_04]: It's not like Warfarin would be immediately therapeutic anyway.

[SPEAKER_02]: So it's not like you have to start on day one because it is risk over time.

[SPEAKER_02]: I often see people three to four or five months after they've had their client in many of them are on a do act and someone might have done the testing and they were positive but by the time they got to me, you know, they were positive and I laid out the data to some people.

[SPEAKER_02]: But then they have some things going on, right?

[SPEAKER_02]: Like, I'd one patient as son was getting married and the timing just didn't work to transition to war-friend and make sure the INR was okay and test because they were traveling.

[SPEAKER_02]: And so we waited until the wedding was over.

[SPEAKER_00]: Interesting.

[SPEAKER_00]: So maybe not every one of those patients needs war-friend right away.

[SPEAKER_04]: Let's summarize this pearl because APLAS pretty much breaks every rule we talked about before.

[SPEAKER_04]: APLAS testing really does change management in a big way.

[SPEAKER_04]: APLAS often presents as young patients with bad clots.

[SPEAKER_04]: These can be big arterial clots, strokes, recurrent pregnancy loss, really bad VTE.

[SPEAKER_04]: These might also be the triple positive patients, the ones you really want to catch and put on war for it.

[SPEAKER_04]: Remember that triple positive here refers to the three tests that we can send.

[SPEAKER_04]: The two antibodies, anti-cardi-lipin, and anti-bated two glycoprotein, and one functional assay, the Lupus anti-coigulent.

[SPEAKER_04]: You should send all three of these early if you're going to test, but remember, only check the Lupus anti-coigulent if you can draw it before you start a blood thinner.

[SPEAKER_00]: And to make a diagnosis, we need to repeat testing in 12 weeks.

[SPEAKER_00]: The key is consistent, high-title positivity over time.

[SPEAKER_00]: So if your initial test shows that your patient isn't triple-positive, time is probably on your side.

[SPEAKER_00]: Of course, involve a hematologist if you're concerned enough to test.

[SPEAKER_00]: It helps to have an expert help you interpret all those results.

[SPEAKER_00]: Alright, I think it's a wrap for Pearl 4 and the episode.

[SPEAKER_04]: That's right.

[SPEAKER_04]: We covered a lot of ground this episode, so we're letting you all add a class early this time.

[SPEAKER_00]: As always, thank you so much for joining us.

[SPEAKER_00]: If you found this episode helpful, please share it with your team and colleagues.

[SPEAKER_00]: Give it a rating on Apple Podcasts or whatever podcasts that you use, it really does help people find this.

[SPEAKER_00]: Tweet us and leave a comment on our website or on Instagram or on Facebook.

[SPEAKER_04]: As always, we love your feedback.

[SPEAKER_04]: Email us at hello at coreimpodcast.com.

[SPEAKER_04]: Opinions express to our own and do not represent the opinions of any affiliated institutions.

[SPEAKER_04]: Thanks for listening.

[SPEAKER_00]: See you next time.

[SPEAKER_04]: Are we really treating them like unprovoked clots?

[SPEAKER_04]: indefinitely?

[SPEAKER_04]: Can we ever de-escalate therapy?

[SPEAKER_04]: I'm going to re-record because my phone buzzed.

[SPEAKER_00]: Welcome to the Kaurai M5 Pearls podcast, bring you high yield evidence-based pearls.

[SPEAKER_00]: I'm Dr.

Marty Freed, general internist and B-addiction assorties.

[SPEAKER_00]: Alright, gosh.