Episode Transcript

Josh Hutchinson: Welcome to The Thing About Witch Hunts.

I'm Josh Hutchinson.

Sarah Jack: And I am Sarah Jack.

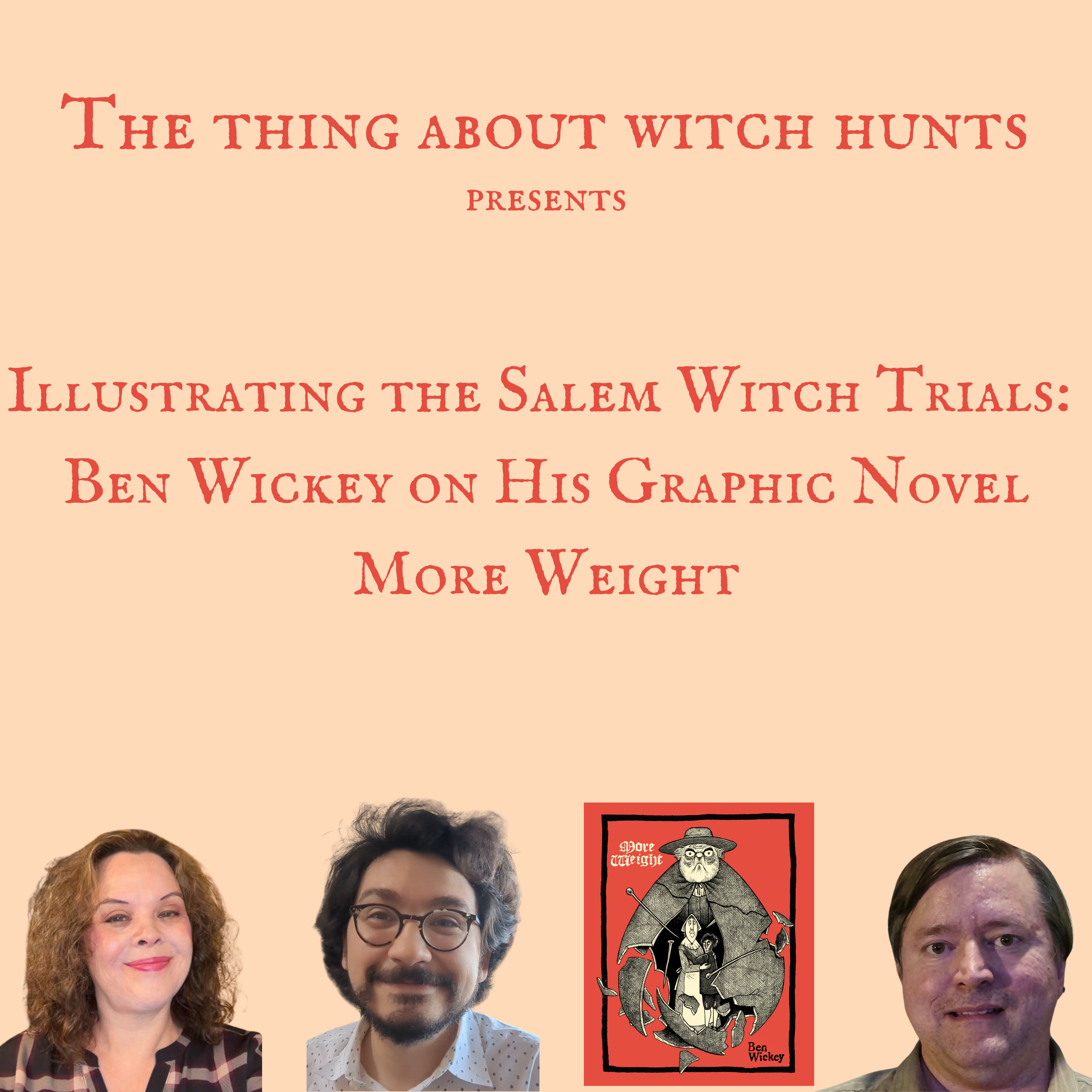

Today, we speak with author and illustrator Ben Wickey about his amazing new graphic novel, More Weight: a Salem Story, which focuses on the story of Giles Cory, the only victim of the Salem Witch trials to be pressed to death under large stones.

Josh Hutchinson: Let's welcome Ben to the podcast.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: Welcome to The Thing About Witch Hunts podcast, Ben Wickey.

Today, we get to talk with you about your new graphic novel, More Weight.

Please tell us a little bit about you and your work.

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Thank you.

I'm a Massachusetts-born illustrator and comic book artist and animator.

I'm originally from Cape Ann of Rockport and Gloucester, about 30 minutes north of Salem, but all my friends live in Salem, so I grew up, you know, going there constantly and soaking up slowly over my whole life the history of that place.

I am a graduate of CalArts.

I did a stop motion animated version of the House of the Seven Gables by Hawthorne as a short, 30 minute short film.

That premiered at the Gables in 2018.

I have been an illustrator.

I worked on a book called The Illustrated Vivian Stanshal, book with Ki Longfellow in 2017.

I'm a contributing artist of Alan Moore's and Steve Moore's grimoire The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic and for 10 years I've been working on this depressing behemoth, More Weight, which is finally out and I'm very relieved.

Thank you for having me.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: So I understand that we're actually all cousins through Mary Easty.

Is that true?

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Yes, and I didn't actually know that I was a dis descendant of Mary Esty until I was halfway through the book doing this.

It was 2018 or something like that.

My cousin Holly in Michigan messaged me out of the blue and said, oh, did you know that we're related to to somebody, somebody from the Salem Witch Trials?

She didn't even know that I was doing this book.

It was under my hat for so long.

It was just this little thing I had on the back burner, little passion project.

And so I think that really changed my attitude towards what I was doing.

It heightened my convictions in what I was doing.

And then we talked a little bit more, and then she provided the genealogy.

I guess I'm her 10th great-grandson.

Josh Hutchinson: Sounds right.

Ben Wickey: On the Ellis side.

So yeah.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: Cool.

Ben Wickey: It was very, it was very moving, very moving revelation.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: Yeah.

I had known that I descended from Rebecca Nurse since I was a teenager, but then about six years ago or seven years ago, I discovered that Mary and Rebecca had grandchildren that married, and then that's the line.

It's all these Russells out of Massachusetts that ended up in Iowa when I was born.

There's something about Mary, because of her petition.

It was such a proclamation and such, you know?

So I can imagine since she was the one that you found yourself tied to, and you're giving such a message with your project, how that must have struck you.

Yeah.

Ben Wickey: It really struck me.

I mean, I hadn't drawn, thankfully, I hadn't drawn her scenes until I found that out.

So it really infused a lot of emotion and yeah, I really felt like I was portraying a family member, you know.

It's kind of, it might seem silly to some people, 330 years on, but no, I really identified with her, and, yes, the book is about Giles and Martha Corey, and I still think they're such an interesting duo to focus on when you consider Giles' obvious flaws and his sort of arc, semi path to redemption, and his death, which I still think is one of the first documented protests in American history.

I think that's very important to, to to look at.

Just drawing Mary Esty, I kind of based her a little bit off photographs of my great-grandmother, Bessie, who I never met, but I gave her her nose and her cheeks and I based Mary Esty off of Bessie.

Sarah Jack: That's awesome.

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Yeah.

Sarah Jack: That's great.

Ben Wickey: And her petition never fails to make me very emotional and teary eyed.

Sarah Jack: Yeah.

Ben Wickey: And it's very similar to, I mean, in the book I do have quotes side by side of Mary Bradbury's petition with her descendant, Ray Bradbury's, message to the Republican party that he put in a, he paid a for a page in Variety in the 1950s at the height of the McCarthy years, where he said let's send McCarthy and his goons back to Salem in the 17th century.

The ripples in time of generations trying to say the same thing, of let's not accuse the innocent, let's protect people.

Let's not give into fear and hysteria and paranoia.

Yeah.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: Yeah.

What do we need to know about the early life of Giles Gory or about him?

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: That was fun.

That was very fascinating.

It's only really Upham's book that kind of touches on the records of Giles' 50 years in Salem before the witch trials.

I went into the now digitized quarterly court records of Essex County, and I just went through the index.

I found all the references to Giles Corey, and I just made lists of all the shenanigans that he was getting into.

And I am pretty much convinced that he did murder a guy 1670s.

Like this isn't a sugarcoated version of Giles in my portrayal of him.

But there is a character composite, a kind of character profile that I created over time of, oh God, this is a guy that got away with practically everything except for the one thing that he didn't do, which was sorcery.

Very colorful, fascinating guy.

You look at his times as a watchman in Salem Town, which is now the city of Salem, above the Salem Town meeting house, which I think would probably be where Rockafella's is, the restaurant is, now in in Salem.

And he's part of a firewood heist on the South River and all this crazy stuff.

Stealing from George Corwin, Jonathan Corwin's father, the sacks loads of household goods and owing people and just debt and just all these sort of things that really create a, colorful, entertaining rogue, a roguish figure and then obviously, a murderer, obviously somebody who had a very dangerous and checkered past that sort of, it all came to a head by the time he was accused of witchcraft.

It was almost as if it was the one thing that they could finally use to dispose of him, because, and this is the same in where witch hunts still exist, India and Africa the moment, as we're sitting here talking.

Accusations of witchcraft have been easiest way to dispose people for the petty, not for supernatural reasons, not for sorcery, not for anything, for the petty, mundane human reasons of jealousy, land lust, petty vengeance.

It always happens in times of socioeconomic pressures and bad economy and things like that.

It was sort of, you know, matter of time for all that to come biting Giles in the bum.

My own version of Giles Corey.

The whole beginning of this book was just simply a kind of graphic novel adaption of this play that I found by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow called Giles Corey of the Salem Farms, in which he gives a portrayal of this man, this Giles Corey is very, very unlike any character that you see anything from Longfellow.

Even his version of Miles Standish is more, you know, Miles Standish, who impaled the heads of indigenous people on pikes, is less grim and angry than this version of Giles Corey.

Part of what the book became was an examination into why did this character of Giles Corey speak to Longfellow and this very tumultuous decade of the 1860s, which had not only the horrific death of Longfellow's wife, but also the Civil War, which his son had enlisted in and barely survived, and the social issues of slavery that he was very, very publicly immersed in.

And so the book became over, at the beginning, it was sort of me going, oh, well, I'll just do a historically accurate version of Longfellow's play, because as I was looking at it, I was thinking, oh, well, I have access to all sorts of historical material that Longfellow didn't have in the 1860s, when all he had was Upham's book, Witchcraft by Charles Wentworth Upham.

And so I I was going through and I thought, well, Giles didn't live on the Ipswich River.

Well, I'll just change that.

And then over time, the Longfellow bits got smaller and smaller.

My own bits got bigger and bigger, thanks in no small part to realizing that Mary Esty was my ancestor.

And the more you research, the more you have an opinion of the facts, which are extremely troubling and relevant and infuriating.

You read the facts, and you're infuriated the basic human level, the injustice and the atrocity of it all, and the ways in which it's still still extremely politically relevant to these despotic times.

That's my rambling answer to very simple question.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: Thank Sarah Jack: We don't consider that rambling, so thanks.

Ben Wickey: I've been working on this book without talking about it, so it's kind of weird talking about it, but Sarah Jack: Yeah, I bet.

I bet.

Josh Hutchinson: Yeah, Ben

WickeyWickey: A lot of fun.

Josh Hutchinson: I really loved what you did with time in the book, how you handled, just weaving back and forth from one period to another, and I just loved that you included the Salem history at the end.

I love Salem, so it's good to see all that history in there.

And it's just so fun time traveling with you.

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Yeah.

And I think that was a, that was really something that I wanted to do because part of the, I I think a big message of the book is that history doesn't happen in a vacuum.

There is such a disconnect, I think, between 1692 and the modern city of Salem that you'll walk through.

So I wanted to, I have a kind of psychogeographical sense of place, wanting to really show that no, everything happens.

History doesn't happen in a vacuum.

It happens in our backyard, and all you need to do is dig, and you need to do the necessary donkey work of getting your pick and shovel and researching and finding all sorts of things, beneath all the hype and beneath all the sort of glittering distractions and the spooky wallpaper and everything.

No.

Beneath that is something really real and human and relevant.

But I did really wanna include these scenes between Longfellow and Hawthorne walking through 1860s era Salem, just not violently thrown back and forth between modern 2025 Salem and 1692 Salem.

There is some midpoint where you can recognize the street corner, recognize how the street layout has remained the same, recognize buildings that still exist from the 17th century, but buildings that still exist from the 19th century and see really see?

itself, how the landscape has changed.

see how the Jonathan Corwin House, now known branded as the Witch House, how that has changed, how that looks completely different in the 19th century and how it was brought back, and understanding people to understand when they visit that city, why they're seeing what they're seeing, why why they look, looks, the way it looks.

because I don't really think there's not enough plaques in the city to tell you.

People are obliged to do their own research, and not everybody has the time or interest to do that.

I wanted to do the book that I looked for in that city but couldn't find, a book that was honest about, oh no, no, this is why this is the way it is, this is why this is the way it is, this changed, this didn't, and you can use it as a guidebook.

You can walk around not only the city of Salem, the whole area of the whole geography of Danvers and Topsfield and places like that to see where these things happened and the traces still left behind, the echoes, the ghosts, the shadows.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: And that's something that you can do with your style of art.

Graphic novels allow for that type of storytelling where a regular piece of literature isn't gonna do that.

Ben Wickey: Yeah.

You can do anything in comics.

I mean, it really allows you a huge canvas of time and space.

You can have as many characters as you want.

You can have as many locations as you want.

A thing that always bothered me, even with very high budget, pristine movie or TV adaptions of the Salem Witch trials, what happened?

Everything happens in the same building.

All of the examinations happen in Salem Village meeting house.

All the trials seem to happen in the Salem Village meeting house.

They never have another location change.

You never see how things get bigger.

You never, once the court of Oyer and Terminer gets put in place, everything moves to Salem Town.

You're moving from the very rustic, rural Salem Village to the more cosmopolitan, opulent, mercantile Salem town.

It's a bigger room, and it's the most sophisticated court.

It's not a kangaroo court.

It's not a, it's not a New Yorker cartoon, where everyone's got buckles on their hats and pitchforks and torches.

No, it is the most sophisticated court that you could be standing in front, albeit an emergency court after return of the charter and a kind of return, because of course, the Massachusetts government had been languishing in legal limbo for a few years.

William Phips comes in, and May of 1692, okay, we have a government now.

We have a new charter.

We're not gonna wait for the general court to assemble.

We're gonna create an emergency court of Oyer and Terminer, let's get these very prestigious, wealthy, land-owning, albeit, but Harvard educated people to stand in judgment of these people that have been accused of witchcraft and to have it in Salem town, the kind of ground zero, if Tad Baker is correct, and I think he is, the ground zero of the Puritan hegemony itself.

It may very, very well may be the place where John Winthrop first made his city upon a hill speech.

It is the first town.

It really was, Salem really was this, a kind of sentimental place for the Puritan hegemony, which was in, by the 1690s, in this kind of visible decline.

And so you see this kind of idea of, okay, not only has Satan obviously declared war upon us, but he's done it, he's really hit it at the heart of, he hasn't done it in Boston.

He's done it at the heart of the Massachusetts Bay colony, in Salem, the first town, the beating heart of the colony.

We can't have the mother country knowing about this.

We've gotta really nip this in the bud.

And so the, not to get too conspiratorial, but of course the priorities shift.

It's less about finding out who is guilty and who is innocent and more about preserving the Puritan hegemony, which was already in a perceived decline, when you consider this new charter, which recognized Baptists, Quakers.

Quakers, we've been boring holes in the tongues of Quakers for generations, and now they are recognized in this new charter.

What next, the antichrist?

What next, atheists and Catholics.

This was a real outrage.

They were just happy to have any charter at all, but of course, Puritanism in New England was perceived to be on tender hooks.

And so this, there's this idea of, okay, if Satan has declared war on us, on New England, then Puritanism has to be visibly winning that war, visibly on top of things.

Of course, William Phips, an illiterate treasure hunter, who has now become governor of Massachusetts, scampers off to Maine to fight the French and indigenous combatants.

And he leaves the government in charge of William Stoughton, not only the Lieutenant Governor, but the chief justice of this new court.

You don't often see this in pop culture portrayals.

You don't often see this in miniseries or movies or things like that.

The whole political catalyst for how this thing was able to reach the heights that it did.

We're always focusing on the afflicted girls.

We're always just trying to figure out why did they, what was their fits about?

Was it Ergotism?

Was it actual fraud?

Was it actual possession?

I'm less interested in that, because I don't really think that the girls are that, I mean, obviously they allowed, they kept this up, but they only had so much agency.

They're little girls in 17th century New England.

They can't admit that this has all been for attention or fraud or whatever, or post-traumatic stress disorder in the cases of some.

You consider some of them were war refugees from King Phillips War.

I'm mostly focusing on the adults in the room, these Harvard-educated people who allowed it to go the lengths that it did.

And no one's talking about that, at least in pop culture.

You see it often, of course, you see the truth in the works of Emerson Baker and Marilynne Roach and Daniel Gagnon and all these amazing people.

Richard Trask.

These are the giants upon which I'm perched as a little vulture with my little pen and ink, drying and scribbling my little drawings.

My hope was to do something that at least in pop culture, which is, comics is a pop culture medium, to do something that was honest about at least the sociopolitical catalysts for everything and how it was all able to happen and how that's still relevant to today, whether in America or whether in places in, as I said, India and Africa, where witch hunts are, actual witch hunts, are still happening.

Yeah.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: In More Weight, I love in the scenes, in the examination scenes, the courtroom scenes at the Salem Village meeting house, you have the characters speak in words that are actually documented in the records that survive.

And I just love that they're speaking in their, basically their own voices.

So thank you for facilitating that.

It really adds something to the story.

Ben Wickey: That for me was one of the most, I hasten the word to say, use the word fun, but it was always a wonderful, challenge and way of working, 'cause I would just go through all the transcripts and highlight the bits that I thought really brought home the gravity of every situation.

And I focused mostly on the examinations of people who had become the victims.

Some non executed people, as well, like Tituba or Mary Black or or Abigail Hobbs or people like that, people that weren't executed, but what they had to say in court is still very interesting.

You read those documents, and they do read like a play.

You wonder why Arthur Miller made up as much as he did.

It's all, the material is itself more riveting than anything he could make up or invent, you know?

And I thought, well, I'm not gonna make anything up.

Why should I?

The truth is here and it's speaking to you.

You read any of the documents, I've, I've been to Rowley, I've handled some of the documents myself.

I handled Martha Corey's examination, which is this giant, parchment folded six ways, and, you really do get very emotional holding it.

This was in the room, and it's thanks to amazing people like Margo Burns.

I mean, they're an amazing, not only an amazing historian, but a linguist.

They were able to study the handwriting and figure out who was in the room and who wrote what, and gave so much more information and insight into what was going on in that room.

It helps people like me who has to draw everything, and I was constantly redrawing so many things.

I started drawing everything in 2017.

I constantly had to go back and redraw things.

Oh, no, no, no, John Hale wouldn't have been in this room or so-and-so wouldn't have come to Salem until this month.

I got to redraw this, or I'm going to replace this person with Nicholas Noyse or whatever.

A ton of redrawing went into this, really because I researched as I went along, which I thought was the wrong way of doing it until I read an interview with David McCullough, who wrote the John Adams biography, lots of great history books about the American Revolution and the Wright Brothers.

And he said, no, no, no.

It's always good to research as you write, because that means that you are working from a perspective of curiosity.

You're asking questions as you go, and so therefore, you are encouraging your reader to also ask, be asking questions, different from doing all of your research and going, this happened because I said so, because I've spent all these years research you know?

So part of the thing that, the effect that I like about what I did is that it does have a Maysles brother inquiring eye documentarian effect, because I'm also looking around the room trying to figure out what's going on and who's in the room and what's happening, as much as anybody else.

And I didn't think that I was in any way an expert on what I was doing.

Even after I finished the book, I thought, I, God, I still barely understand this, it's so confusing.

It's such a insane episode of our history.

Until I had dinner with Margo Burns and they patted me on the shoulder and they were like, no, no, no, no, no, you're one of us.

No, no, you're not a historian.

I tell people, I'm not a historian.

I'm just a cartoonist who cares.

If I've gained any expertise in this subject, I, I'd be very happy to say so, but I'm glad I left it up to someone else to say that.

It's one of those bits of history where there's still so much that we don't, not so much that we don't know in, in terms of the innocence of people accused is not, it's not as if there's still room for doubt as to whether there was actual witchcraft or blah, blah, blah.

That's very well established that no such thing happened.

But it's still a thing where you, you do a whole, you do a 500 page book like this, and you're still rubbing your chin going, oh God, I still wanna know.

I still have questions, but thankfully, the thing about this book that I am proud of is that there are about, at least like 30 pages at the end of research notes that say exactly what I invented, what comes from primary source documents, what comes from Longfellow, what comes from, you know, who said what, what is a theory from such and such a historian, where this building is now, what happened to this, what this person later went on to do, when did this person die?

It's a book in and of itself.

He just sat, I sat in this chair writing out all these research notes.

I wish I took notes while I was researching so I wouldn't have to go through all the research books in the shelf behind me and going through the index, trying to figure out where I got all the things that I got, but just to show, just to be, what's the word, upfront and transparent with people.

There's some things that happen behind closed doors that I can't prove, but I'm going to at least tell you that, this bit is something that I wrote this bit is something that somebody else wrote this bit is, this bit comes from actual documents because the truth is so much crazier than fiction.

There's some bits, what is it, the death of Daniel Wilkins?

You read that and you're like, no, I, there's no way that that could have actually happened.

It did.

And, yeah.

it's a bizarre episode of our history that you need to back up with some sources.

Sarah Jack: Yeah, I just wanna say as a podcaster on the subject of witch hunts, as a descendant, and then just as a enjoyer of literature and comics, coming from all those perspectives, when I got to view your work, the first thing, I was so excited because I could see it was gonna be a journey that I was gonna like go to Salem, like back through time, although you see the layers of time in it, and right away I was like, I wanna be in the space.

I wanna see how Ben tells the story.

And you just, as you mentioned, it's a big book and it has all of this art and the words from the past and your notes and the input from the historians.

It's all there, but you go through it a panel at a time, a page at a time.

Plus all of your storytelling with your visuals is so incredible.

It's just really phenomenal.

And it's enjoyable to spend time in More Weight.

It's enjoyable to go to this space that is like, it's a raw space, it's a truthful space.

And, yeah, I'm so grateful that you put the work in and gave it to the world.

We need it.

We've needed it.

More pieces of history need to be done like this and, but I'm so grateful that it's our ancestors' history, and it is such a essential part of understanding American history and American present.

Ben Wickey: Yeah.

I thank you so much for that.

It's very, very, very kind of you.

I finished the book.

I didn't know what people were going to think of it.

It's been very gratifying to just look behind my shoulder occasionally and see people behind me.

I get a kick outta that.

It's very rewarding for me, especially after just having this on the back burner as just a 10-year labor of love of, just doing other things and then always going back to this book and just taking as much time and effort as I could into just trying to make it as good as I could and as accurate as I could.

Yeah.

And I think every generation, I think it's a story that should be told with every new generation.

I think every new generation should have some new way of telling the story.

The way I think about it is that it really is America's best example of a, what happens to all theocracies, ultimately they will crumble.

With the very first hint of anything from the invisible world, you're going to of course get demonization and people at each other's throats, and who said it?

Cotton Mather, mauling each other in the dark.

And it is also, of course, America's best example of what happens when a society can of course, tear itself apart from the inside with intolerance and blind faith and petty vengeance and hatred.

I think Gore Vidal was right, that we do live in the United States of Amnesia.

We tend to remember episodes of our history that we're comfortable with, ones that make us look good.

And the Salem Witch Trails, this whole pandemic of fear is a blight.

It is not something that is easy to swallow.

19 men and women hanged and one man pressed to death and five people dying in jail, including a newborn baby.

That's really tough to swallow.

It's especially really tough when you look around at modern day Salem, where all this stuff happened, and you say, actually none of this spooky stuff would be going on if there weren't 19 men and women hanged and one man press to death.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: Yeah.

Ben Wickey: It, I don't think people are asking enough questions.

I think there's a cognitive dissonance.

I think that a vital point has repeatedly been lost, and I think there's a lot of really good opportunities to tell the story, especially in these, as I said, despotic times.

I mean, these times where you've got families being torn apart and people being deported and children being arrested and all that.

I don't see anybody walking around Salem making that connection.

I also don't see many people in Salem talking about how witch hunts are still happening in the world as we're sitting here comfortably in our chairs, in our homes, in our secular democracy, in our post enlightenment times with our enlightenment values and our secular laws.

We're not really talking about how this is all still going on.

And because of that, we are failing to recognize repeatedly that our brothers and sisters across the Atlantic, their present nightmare used to be ours.

And if we don't understand what witch hunts actually were and meant in America and in Europe, then, in the West, then we can't really empathize with what's going on in India and Africa.

We sit back and we buy our $80 wands, and we think, they're, that's just how they do things over there.

That has nothing to do with what happened in Salem in 1692.

No, it has everything to do.

Witch hunts happen for the same reason.

And it's the kind of boring, human, mundane reasons, as I said, of land lust and jealousy and somebody refuses my sexual advances, or I want that guy's land, or whatever.

There's always going to be the button to push for the invisible world, for witchcraft.

That's how it existed in history.

The word witch, it developed through Christianity as a way for Catholics and Protestants to demonize each other and for all of them to demonize Jewish people.

That's how the word witch grew over time.

I think we've kind of lost that.

I think a really, troubling and, to me, depressing mixture of pseudoscience and pseudo-history has stunted not only Salem's progress towards perfect hindsight, but America's.

And this book, yeah, it's a little angry at, at the end.

I didn't expect to do a polemic.

I didn't start this book setting out to do, you know, I'm going to pierce the magic bubble of modern Salem.

I didn't think my pen was going to be that sharp to pierce that bubble, but the more I researched, the more I, of course, empathized with these people from history.

The more I drew them, mean, drawing them is a completely different wor, I mean, that's an experience, you know.

The more angry I got.

The more I had an opinion.

If you set out to draw a Giles Corey for a graphic novel, you're, most people would probably, the first thing they would draw is him being pressed to death, or you're gonna draw people being hanged or that kind of thing.

I wanted to know who these people were.

I set out to draw these people as they were.

I was putting off for many years of this project any drawings of these people being executed or suffering slowly or the agonies of these people because I didn't feel like I had that range when I started out.

I thought this is gonna be something I'll have to draw, but I will take absolutely no pleasure in doing so.

So I started out drawing Giles Corey.

By the time I drew Giles Corey being pressed to death on September 19, 1692, I had been drawing him for nine years, and I had drawn his entire life.

I had drawn his baptism.

I had drawn all three of his marriages.

I had drawn all the shenanigans and things that he had gotten up to in Salem.

I had drawn his crossing across the Atlantic.

I had drawn his children growing up, and that's different, and so it, it meant something more, when it finally came time to saying goodbye to him, to Martha, of course, to Mary Easty, to everybody.

I had tried as much as I could to empathize and humanize these people, to get to know them, to not just look at them as collateral damage or witchcraft fodder or as saints or martyrs, but to look at them as human beings who senselessly suffered.

I just really wanted to get this right on a human level, on an empathetic, compassionate level, and to convey that to readers of yes, these people may have had buckles on their shoes.

Yes, they may have practiced, to our minds today, a kind of extremist form of faith.

But they still had jealousies and they still had love and they still had the fear of death and they still wanted to avoid pain and to achieve some kind of happiness and fulfillment in life the way that any of us do today.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: It's so important to show the humanity, to allow the reader to empathize with the subject, because that's how you get into understanding somebody is seeing them as a human, and you can relate more to the experience, and maybe it moves you to change your own behaviors or something of that nature.

Ben Wickey: Yeah.

And also to show the antagonists not as mustache-twirling villains, but as people who think they're doing the right thing.

Everyone has their own reason for doing what they're doing.

I mean, okay, my portrayal of Thomas Putnam is a bit mustache-twirling Snidely Whiplash, I gotta admit.

But, no, it's good to always just remember be, you gotta remember why people do these things, because that's your only real insight into understanding how they still happen, how they happen at all, what happened in Salem wasn't the first witch trial or witch hunts in American history, wasn't the last either, but they are the biggest, they are the most documented or well-documented.

And, because of that, you can really look into people's lives and look into letters and look into writings and trying, just trying to figure out how people were feeling about what they were doing and why they were doing it and what they were doing.

Yeah.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: How does it feel to know your work will inspire a new generation of artists and storytellers?

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Oh my gosh.

I haven't really thought of that.

It wasn't really my thought while I was doing it.

I think my process for doing it was so isolated, and so it's just trying to exercise something out of myself, trying to get something off my chest so that I could understand it.

But of course then I finished it, and a really estimable guy in Canada has created a whole study guide for the book.

So it could be syllabilized and taught in schools and things like that.

I really do hope that it is a tool, a learning tool.

My quarrel with the Crucible is not the fact that it is fundamentally historically inaccurate.

Arthur Miller at the time said, this is not meant to be a historically accurate play.

My beef with the Crucible is how it is taught in high schools instead of the actual history.

If you're gonna be teaching American history in public schools in America, you're gonna be talking about what the Pilgrims, you've got the Mayflower, and then you're just jumping to the Revolutionary War there's this whole, like 70 years between, that is very fascinating.

You've got not only the witchcraft trials, but you've got King Philip's War, which was one of the catalysts, I would say, for what happened in Salem.

You've got all these events that happened in between, and my hope is that, if you're gonna be teaching a class and the works of Baker or Roach are perhaps dense for a high school class or something like that, I hope this can offer something, some, with young people or just anybody who picks up the book.

I, I hope that it helps people and that it encourages people to think.

I am a cartoonist.

It's not my job to convince people of my own convictions and my own opinions.

It's not also my job to BS people or to give people what they want.

It's my job to just be honest about how I feel about things and to just allow people to think differently.

And if the book does that, then I've done my job as a cartoonist.

And it is also my hope to, I guess, make the jobs of historians a little easier, to have a book in pop culture that dismisses the ergot theory or puts The Crucible in context with the actual history, just so that historians can go about their days not being asked really weird questions.

If you have this kind of book in pop culture, in the bloodstream of American pop culture, then that can't hurt.

But as to its impact, I have no clue what's gonna happen.

I hope it'll help.

Josh Hutchinson: I think it will.

And I think that More Weight is a must have for any home of anybody who's interested in Salem to any degree.

It's great for beginners.

It's great for intermediates.

I loved it myself for being taken back visually to see the things that I've been reading about for years, to be there.

So I definitely recommend it to everybody.

It's available September 23rd?

Ben Wickey: September 23rd.

Yep.

And I'm gonna be starting a book tour on the Northeast of different places, where I can give talks and sign a copy of the books if anybody's interested.

Oh, September 26th, I'm going to be at the Sawyer Free Library in collaboration with the Bookstore of Gloucester.

I'll be in Gloucester, Massachusetts that day kicking off the Massachusetts book tour.

October 4th, I'm going to be doing a talk at the House of the Seven Gables in Salem.

So far, it's the only place in Salem where I will be doing this book, as a tour and q and a and book signing.

October 18th, I'm gonna be at Jabberwocky Books in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

October, I think 10th to the 12th, I'm gonna be at New York, New York, ComicCon.

And in November 15th, I'm going to be a keynote speaker at the Festival for Nonfiction Comics in Brattleboro, Vermont.

So far that's the book tour.

I'm doing a bunch of stuff.

I'm bracing myself for, Sarah Jack: gonna be a blast.

Ben Wickey: Yeah, I'm very looking forward to it and engaging with people when, yeah.

Sarah Jack: Yeah, that'll be a blast.

When you're at the House of the Seven Gables, take a look at their little walkway brick project.

We haven't been there ourselves to see, but we, were able to have a brick placed for Tituba that says In memory of Tituba.

Ben Wickey: Ah.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: And so that, that's there, I believe, behind the facility, near the parking lot, but Ben Wickey: Yay.

I have a brick for my friend David Frankham there, who was the voice of the, the narrator for the House of the Seven Gables that my, my short film got a, he's got a brick there, and he's gonna be 100 years old this February and still going strong.

Sarah Jack: Awesome.

Great.

Ben Wickey: Yeah.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: Great.

Thank you so very much.

Ben WickeyBen Wickey: Oh my gosh.

Thank you both so much.

Oh my God, this was so much, this was so great.

I've been a long admirer of everything that you guys do on this podcast and the detail and the commitment that you both have on a day by day basis.

Oh my goodness.

You guys are definitely after my own heart, and it's been really great manifesting among you today.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: Great.

I've enjoyed it so much.

I could carry on for hours talking about this, so thank you.

Ben Wickey: Me too.

Sarah JackSarah Jack: Thank you for joining us.

Josh HutchinsonJosh Hutchinson: This interview is also available in three parts at The Thing About Salem podcast, and More Weight is available for pre-order now.

Sarah Jack: Order your copies today at bookshop.org/shop/endwitchhunts.

More Weight is intended for mature audiences.

Josh Hutchinson: Have a great today and a beautiful tomorrow.