Sidedoor

·S12 E2

A Mold with a Grudge

Episode Transcript

Sidedoor (S12E02) – Penicillin Man final web transcript

Lizzie Peabody: This is Sidedoor, a podcast from the Smithsonian with support from PRX. I'm Lizzie Peabody.

Lizzie: A lot of scientists from the early 1900s were known for being ... quirky. Albert Einstein famously didn't like to wear socks. Marie Curie hated public speaking so much she almost skipped her own Nobel acceptance ceremony. Nikola Tesla refused to speak to women wearing pearls, and would only stay in hotel rooms divisible by three. And then there was this guy, Alexander Fleming.

Kevin Brown: This was a man who could stand and stare at you for an hour without saying a word. He didn't feel uncomfortable—you would.

Lizzie: This is Kevin Brown, trust archivist at St. Mary's Hospital in London, and curator of the Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum. He says Fleming was a bit of an odd duck.

Kevin Brown: To his colleagues at St. Mary's, he was known as 'Flem.'

Lizzie: Flem was short, wore a bowtie, and smoked three packs a day. And he had an unusual hobby.

Kevin Brown: He was interested in art. He didn't use oils of watercolors, he did what he called germ paintings.

Lizzie: Fleming was a bacteriologist, so he studied and taught about bacteria for a living. But bacteria often grow in bright colors, which he liked to use to create artwork—germ paintings.

Kevin Brown: Basically, painting by numbers with bugs.

Lizzie: And that is why, in the summer of 1928, Fleming went on vacation and left a bunch of Petri dishes sitting out in his lab at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School. You know, just in case some grew into cool colors while he was away. And when he returned at the end of the summer, he opened the door and went "Ah! Exactly how I left it."

Kevin Brown: Cluttered. It's musty. It's dusty.

Lizzie: But not exactly as he'd left it. As he peered into the Petri dishes he'd left out, he noticed something strange.

Kevin Brown: One of them he looked at and he said, "Hmm, that's funny."

Lizzie: What was he seeing?

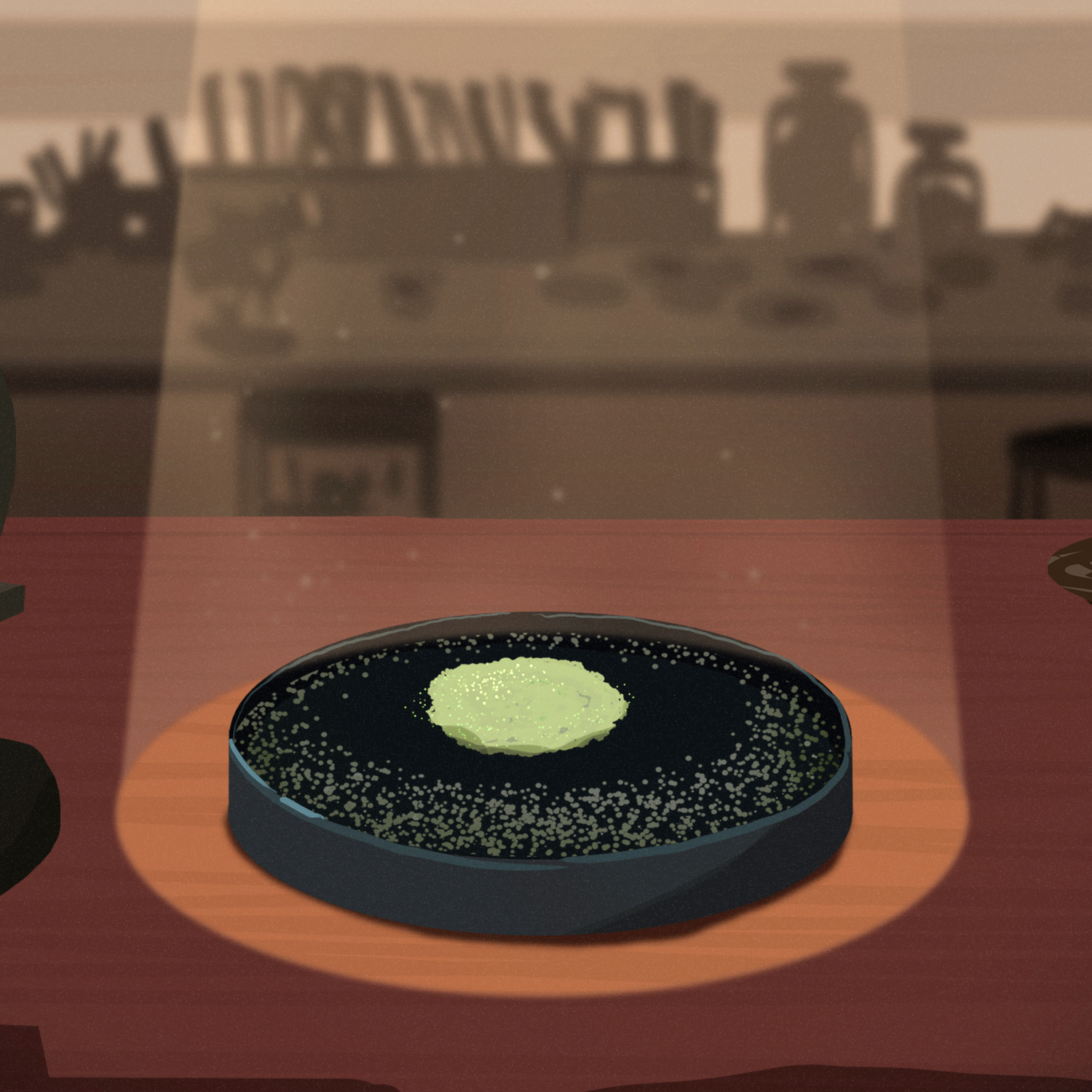

Kevin Brown: What he saw was that the Petri dish had become contaminated by a fungus.

Lizzie: But it wasn't the fungus that interested him.

Kevin Brown: What interested him was not what was there, it was what was not there.

Lizzie: Fleming was studying the growth of staphylococcus bacteria, which should have covered the entire Petri dish.

Kevin Brown: Close to the mold, though, there was nothing.

Lizzie: Surrounding the mold, there was no bacteria at all. And Fleming thought, "No. No, could it be?"

Kevin Brown: The fungus had produced something that stopped the growth of the bacteria.

Lizzie: It was some sort of anti-bacteria. And Fleming had the perfect name for it.

Kevin Brown: Mold juice.

Lizzie: The mold was penicillium notatum. And as Fleming began to study the effects of the mold on bacteria, he wrote a paper to present to his colleagues, at which point he figured, "I gotta workshop this name a bit."

Kevin Brown: "How about no, not mold juice. How about penicillin?"

Lizzie: This time on Sidedoor, the fungus that would become a humungous discovery, but not without a monumental effort—and a little luck. It would take a sick policeman, a world war, transatlantic collaboration, private industry and a market cantaloupe to turn mold juice into the modern medicine that would affect all of our lives. That's coming up, after the break.

***

Lizzie: It smells like—it smells like my biology classroom in here during the era when we dissected cats.

Diane Wendt: Oh that's terrible.

Lizzie: Like formaldehyde.

Diane Wendt: Well, I actually love the way most of our collection smells.

Lizzie: Really?

Lizzie: I'm in the medical history collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History with curator Diane Wendt.

Lizzie: Can we look at the mold that we have?

Lizzie: We can look at the mold we have.

Lizzie: She's showing me a little glass case containing the mold penicillium notatum, the same mold Alexander Fleming saw in his Petri dish nearly a hundred years ago in 1928.

Lizzie: So can you just describe what it looks like?

Diane Wendt: It does look like mold. It's ...

Lizzie: [laughs]

Lizzie: I mean, Diane is not wrong. It looks like something you'd recognize: fuzzy, gray and white, like mold you'd find growing on an overripe peach.

Lizzie: It's got little almost like wrinkles, the way that you see with the rind of cheese wrinkle sometimes.

Diane Wendt: A little bit, too. Yes.

Lizzie: Yeah, it's got a little bit of a brainy waver to it.

Diane Wendt: It does.

Lizzie: It wasn't even a hundred years ago that Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. Today, it's such an important medicine, it's hard to imagine a world without it—but let's give it a try. In the early 1900s, before modern antibiotics, people died of all kinds of things.

Diane Wendt: Pneumonia, tuberculosis. Those were both very big killers.

Lizzie: But so were ear infections, tooth infections, eye infections.

Diane Wendt: Any kind of infection, the kind of staph or strep.

Lizzie: Strep throat could be fatal. Even falling off your bike and skinning your knee, or pruning a hedge and scratching your arm could lead to an infection that could kill you. Think about that. Have you ever had a sore throat or a deep cut or an earache? Any one of those might have killed you a hundred years ago.

Kevin Brown: There wasn't much that doctors could do to deal with infectious disease.

Lizzie: Archivist and curator Kevin Brown again. He says if you were unfortunate enough to need surgery at a hospital ...

Kevin Brown: And then got an infected wound, you were just as likely to leave dead as you were alive.

Lizzie: And fatal infection after childbirth was so common in hospitals that in most cases it was safer for women to deliver a baby at home.

Lizzie: But the turn of the century marked a changing point in modern medicine, because germ theory, the idea that specific germs cause specific illnesses, was becoming increasingly accepted. Scientists were beginning to develop treatments for specific germs, like a serum to treat diphtheria, a deadly childhood disease.

Diane Wendt: Which killed a tremendous amount of young children. And so to have a therapy that was actually effective against it, you know, seemed pretty miraculous.

Lizzie: Suddenly, long-time killers like smallpox and typhoid were treatable with vaccines that worked. The lab coat was the new superhero cape as the public got swept up in the potential for miracle cures.

Diane Wendt: You got this idea that conquest of disease is—it's not here yet, but maybe, you know, it's just over the horizon.

Lizzie: Hmm.

Lizzie: But when it came to fighting infection, doctors still only had a few options.

Diane Wendt: So one of 'em I pulled out, which is pretty standard, is carbolic acid.

Lizzie: Oh!

Lizzie: Diane holds up a dark brown bottle from the museum's collections.

Lizzie: It looks like a whiskey bottle.

Diane Wendt: It does look like a whiskey bottle.

Lizzie: Except across the top is written ...

Diane Wendt: "Poison."

Lizzie: [laughs]

Diane Wendt: Not to mistake it for a whiskey bottle.

Lizzie: Under that it says ...

Diane Wendt: "For use in disinfecting cesspools, stables, water closets, hen houses, sheds, barns, hospitals and privies.

Lizzie: Wow! Cesspools and hospitals in the same sentence.

Diane Wendt: Well, closer than you probably want to think of the kinds of germs they have to deal with.

Lizzie: Carbolic acid was one of the most common tools for fighting infection around the turn of the century. It's an antiseptic used to kill bacteria, viruses or other bad stuff in living tissue. It's typically used outside the body, but the problem with an antiseptic like carbolic acid is that, well, it kills everything!

Diane Wendt: So the idea that you can kill a germ, or at least keep the germ from replicating is one half of it, but the other half when you're talking about the human body is will that substance do irreparable harm to the human body? So it's that balancing act.

Lizzie: You want to kill more of the unhealthy things like bacteria than you do healthy human cells.

Diane Wendt: That's really where the difficulty lies. So you had earlier drugs that were effective, but they were limited also by their toxicity.

Lizzie: Effective, but at what cost?

Diane Wendt: You know, what doesn't kill you, makes you stronger. Or ...

Lizzie: [laughs] Is that—is that always true?

Diane Wendt: [laughs]

Lizzie: It's—it's not always true. And nobody knew that better than our guy Alexander Fleming. Remember ol' Flem? During the First World War, he'd worked in battlefield hospitals in France, treating soldiers wounded in the brutal conditions of trench warfare. There, he saw countless soldiers die, not from their wounds, but from the infections that followed. Deep, dirty shrapnel wounds from the trenches were breeding grounds for bacteria like staph and strep, and antiseptics like carbolic acid were making things worse. The acid killed the bacteria on the surface of the skin, sure, but it couldn't penetrate deep enough into the wounds, and often damaged the tissue, making it harder to heal.

Lizzie: Fleming left the war determined to find a better way to fight infection, a way to target the bad bacteria without harming the healthy tissue. And he knew that microorganisms in nature are constantly competing with each other to survive.

Diane Wendt: So this is basically what you're getting at when you're getting at the antibiotic and the antibiotics that we use today is that you're taking advantage of a natural property of a micro-organism to fight another microorganism.

Lizzie: To establish its domain and fight off any competing microorganisms.

Diane Wendt: Right. Right. Competition, natural competition between microorganisms.

Lizzie: So when Fleming stumbled on penicillin years later, in 1928, what he'd found wasn't just mold, it was a mold with a grudge—specifically, a grudge against staphylococcus bacteria. Think of it this way: If carbolic acid was like a carpet bomb, destroying everything in its path, bad and good, then penicillin was like a company of trained foot soldiers, adept at weeding out what they perceive to be enemy agents, while for the most part leaving the city streets intact.

Lizzie: But the penicillium notatum mold wasn't yet a well-trained company of foot soldiers. Fleming had some work to do. After discovering this bacteria-fighting mold, Fleming knew the next step was to isolate and stabilize the active ingredient in the fungus, which he'd named penicillin. So he set out trying to extract enough mold juice to be able to experiment with.

Kevin Brown: Effectively, he's got the idea of penicillin as an antibiotic. He's got the idea, he publishes the idea ...

Lizzie: And nobody pays any attention.

Diane Wendt: It just didn't make a big splash with, like, his colleagues or anything. And I'm sure, you know, part of it is his own character and personality.

Lizzie: For all his lovable idiosyncrasies, Fleming was not known to be a very charismatic speaker—to say the least.

Lizzie: I heard him described by students as, quote, "The worst lecturer they'd ever had."

Kevin Brown: That's a good description of him.

Lizzie: Fleming was a dazzling, shining beacon of a model of what not to do.

Kevin Brown: He mumbled. He assumed his audience knew as much as he did.

Lizzie: Oh dear.

Kevin Brown: And so he didn't explain a word.

Diane Wendt: I've heard that most people couldn't hear him. [laughs] That he was so soft spoken that even some of his students said that they just didn't hear what he said.

Kevin Brown: Also, he thought that if there were no questions at the end of a lecture, it was because he'd explained everything perfectly clearly so there's nothing more to be said.

Lizzie: So his colleagues at St. Mary's are like, "Oh, Flem. There he goes mumbling about bacteria again. Cool story, bro." But Fleming ups the ante. He arranges to give a lecture at the Medical Research Council Club, an elite scientific society in London. And ...

Kevin Brown: Again, that lecture goes down like a lead balloon.

Diane Wendt: [laughs] I don't even think it was a lead balloon, because that seems like that would go thump, anyway.

Lizzie: Oh, it didn't even make a sound.

Diane Wendt: Yeah.

Lizzie: [laughs]

Lizzie: There was another reason the scientific community wasn't exactly leaping out of their chairs at Fleming's findings. They were like, "Well, we literally just developed an effective antibacterial: sulfas." Sulfa drugs were new on the scene in the early 1930s. Developed in Germany, they were one of the first antibacterials that could be taken internally and fight infection from within.

Diane Wendt: And they were a wonder drug.

Lizzie: Really?

Diane Wendt: Yes.

Lizzie: In 1936, the New York Times reported that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's son, FDR Jr., was dying of strep throat when he was treated with a brand new sulfa drug that cured him.

Diane Wendt: So there was a tremendous amount of attention on that at the time. And again, you know, if you have something in hand that's sort of working and everyone's focused on it, it's very easy not to jump to what seems to be like the new idea that's a little bit unproven, right?

Lizzie: The weird mold.

Diane Wendt: Yes, the weird mold.

Lizzie: With sulfas getting all the attention, Fleming and his weird mold were sidelined. And despite his best efforts, he couldn't isolate or stabilize enough to perform experiments to prove what he saw as its clinical potential. He'd taken it as far as he could on his own. So he went back to his regularly-scheduled classes and research, chain smoking alone in his lab. But unbeknownst to him, a team of researchers outside of London were conducting their own experiments with Fleming's mold juice.

Lizzie: Some scientists at Oxford were building on Fleming's work, and within a few years, they had successfully extracted enough penicillin to inject it into mice. These mice had been infected with a deadly disease and then separated into two groups. The first group was the control group. They got no medicine. The second group got penicillin.

Kevin Brown: Dramatically, within a few hours, all of the control group were dead, but all of the mice who'd been given penicillin were still alive.

Lizzie: Finally, proof of the clinical potential of penicillin. The team, which included Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley, published their findings in 1940.

Kevin Brown: And their success was down to the fact they were working as a multidisciplinary team of men and women scientists bringing different approaches to solve a common problem.

Lizzie: If Florey was the strategist and Chain was the chemist, then Heatley was the engineer. He'd designed new ways to extract and purify the fragile mold compound, stabilizing it into an injectable form.

Lizzie: By now, World War II had broken out. England was at war, and the need for antibiotics would soon be greater than ever. But as bombs fell on London, the Oxford team kept calm and carried on. They spread mold spores in the lining of their coats, so that if the lab got bombed or they needed to leave quickly, they could continue penicillin research abroad. They prepared to test penicillin on their first human subject: a policeman with an infection that had gone septic.

Kevin Brown: According to one story, he was injured in a bombing raid on Southampton.

Lizzie: His face was covered in abscesses, he'd lost an eye and there were abscesses on his lung. He was clearly dying. There was nothing to lose and everything to gain by trying penicillin. And at first, it seemed to be working well. The man began to recover.

Kevin Brown: But there were two problems: One was the only penicillin they had was what they could make in the lab themselves.

Lizzie: So there wasn't enough to treat a grown adult. The second problem was that the penicillin they gave him didn't stay in his body very long.

Kevin Brown: So they would station someone at the foot of the man's bed.

Lizzie: And collect his pee.

Kevin Brown: Cycle with it back to their labs, extract any usable penicillin and reinject it.

Lizzie: But even with the team recycling urine around the clock, soon there wasn't enough usable penicillin left to fight the infection and the policeman died.

Kevin Brown: So the next patients they used it on were children or people with less severe illnesses who didn't need as much.

Lizzie: A 15-year-old boy with an infection after a hip operation made a full recovery. A six-month-old baby with a urinary tract infection was cured. Four patients with eye infections were successfully treated. In the context of the day, these recoveries were miraculous, but as excitement in penicillin was growing, so was the scope of the war.

Diane Wendt: England is at war, so they're working at a very difficult time with very limited resources.

Lizzie: At Oxford, the team was using anything they could find to grow as much penicillin as possible as quickly as possible. But it wasn't easy. Lab technicians known as penicillin girls would fill bowl-like vessels with liquid broth—food for the mold. And the mold would grow on top of the broth.

Diane Wendt: The bedpans were some of them that worked best.

Lizzie: The bedpans?

Diane Wendt: Bedpans.

Lizzie: Bedpans made good penicillin vessels because they were shallow and wide. And as the penicillin mold would grow across the top of the broth like foam on a latte ...

Diane Wendt: The penicillin itself is being deposited in all that liquid underneath. That's the mold juice, if you will.

Lizzie: Then a chemical separation process would extract the actual penicillin from the juice. It was small-batch brewing, super time intensive. And the war was interfering. Regular German bombing meant production needed to be spread out so no single bomb could take out all of penicillin production. But that meant they were brewing this precious medicine in teacups—or bedpans—when they needed to be brewing it in swimming pools. So what was Britain to do? It was time to call on the Yanks.

Lizzie: Penicillin production leaps the pond—after the break.

***

Lizzie: We're back, and here's where we are: In 1928, bacteriologist Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. In 1940, scientists Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and Norman Heatley were part of the team that unlocked its potential to become a miracle medicine.

Lizzie: But WWII had crippled Britain's ability to manufacture penicillin at any kind of scale. So in July 1941, Florey and Heatley hopped on a plane bound for America, carrying with them samples of mold. The United States hadn't entered the war yet, but preparations were afoot.

Kevin Brown: That year, Roosevelt had set up the Office of Scientific Research and Development to prepare scientifically and medically for what was seen as inevitable involvement in the World War. And penicillin was one of its major projects.

Lizzie: Norman Heatley headed straight to the Ag Lab—the US Department of Agriculture's Northern Regional Research Lab in Peoria, Illinois, smack dab in the middle of the corn belt.

Diane Wendt: It was suggested to him that, you know, that's the place to go for government research. And indeed that turned out to be very fruitful. [laughs] Literally very fruitful.

Lizzie: [laughs]

Lizzie: You'll get the joke in a second. The Ag Lab had been set up as part of the New Deal, and it had big tanks for fermentation.

Kevin Brown: And there they developed a new production method.

Lizzie: This new method would make use of the lab's deep fermentation tanks. Instead of growing mold along the surface of the liquid, they wanted to grow mold inside it, basically creating those swimming pools of mold juice. But first, they needed to find the best possible food for the mold, and being in the corn belt, surrounded by fields and fields of corn ...

Diane Wendt: They were also always looking for ways to use agricultural byproducts.

Lizzie: And one of the byproducts of cornstarch production was this thing called "corn steep liquor." So they figured why not throw that in the tank?

Diane Wendt: You know, they always say, like, "Well, we would've tried it, because we tried it on everything, you know?"

Lizzie: [laughs]

Lizzie: But it just so happened that the penicillium mold loved that sweet, sweet corn stuff! It boosted penicillin yield twelvefold. But there was a problem: The Fleming mold didn't like growing in deep tanks, so they needed to find a different strain of penicillin that could grow submerged, not just along the liquid surface.

Kevin Brown: So there was a worldwide search to find a better strain of penicillin.

Lizzie: Mold samples came flying in from hither and yon.

Lizzie: So people sent in moldy bread, moldy fruit.

Kevin Brown: Moldy jam juice.

Lizzie: Moldy shoe leather. Like, all of it.

Kevin Brown: Yes.

Lizzie: But sometimes what you're looking for is in your own backyard. The winning mold came from a local market.

Diane Wendt: The mold that, you know, really took off was found on a moldy cantaloupe that was brought into the lab. And who exactly brought it in is, you know, cloaked in mystery a little bit.

Lizzie: The story goes that it was a woman named Mary Hunt who worked at the lab.

Diane Wendt: She kind of got renamed "Moldy Mary." And thus, you know, kind of a myth is born, I guess, you know? "Moldy Mary."

Lizzie: Whoever brought in the cantaloupe, it was a fruitful find—see? The joke makes sense now. Supported by the federal government, all the research pieces were now in place. They had the right variation of mold, and they had a new way of growing it in these much bigger batches. Now all they needed was the industrial capacity to get penicillin to every Allied soldier on the battlefield.

Diane Wendt: So that's where the American companies come in.

Lizzie: In the fall of 1941, the US government reached out to all the major American pharmaceutical companies and said, "All right, guys. Time to start making this penicillin stuff, stat." And ...

Kevin Brown: They met with polite interest, but nothing more. It wasn't commercially viable for these firms.

Lizzie: It wasn't gonna make them money.

Kevin Brown: It wasn't. [laughs] Not at all. No money in it for them to produce from the mold.

Lizzie: See, American pharmaceutical companies thought making penicillin from finicky mold was a fool's errand. They figured they could wait until they'd figured out the chemical structure of penicillin, and then synthesize it from scratch. But just a month later, in December, 1941, the US government convened another meeting with these companies. And this time, pharma couldn't wait to get involved with penicillin.

Kevin Brown: Now what made the difference was this was 10 days after Pearl Harbor. But don't think it was just wartime patriotism that motivated these hardheaded industrialists.

Lizzie: Overnight, penicillin became profitable.

Kevin Brown: The military wanted penicillin. They wanted the benefits of it. They didn't care if it came from a mold or if it was synthesized. What they wanted was something that would give them a military advantage. If you could get your sick and wounded back into action more quickly than your enemy, it did give you a distinct advantage over that enemy.

Lizzie: Allied forces would soon be losing an estimated 2,000 people a day, many to infections. And the federal government did everything in its power to usher penicillin production along: tax advantages, special access to materials and labor. It even exempted penicillin from antitrust laws so that companies could freely share information. This was the reverse side of the horrors of war.

Diane Wendt: It creates teamwork that you would never find at any other time, and the government helped pave the way for that.

Kevin Brown: That was one of the wonders of penicillin, the fact that people were working together that would be commercial rivals.

Diane Wendt: In the end there were about 20 companies or so involved, but the big ones were the Squibb company, Pfizer company and Merck. Those were probably the first big three that were really working together. Pfizer had more experience with fermentation.

Lizzie: You probably recognize the name Pfizer today—they're a pharmaceutical giant. But back in the '40s, they were not in the pharma game. Pfizer actually made citric acid for soft drinks. That, however, made them experts in fermentation—exactly what penicillin production needed. But they didn't want to risk contaminating their citric acid with—well, mold. So they built a whole new facility just for penicillin.

Kevin Brown: Ironically, that's how Pfizer became a big player in the pharmaceutical industry. They hadn't been involved in pharmaceuticals before that!

Lizzie: And they're like, "Well, now we have this custom-built lab for pharmaceuticals, we might as well just double down?"

Kevin Brown: Yes.

Lizzie: They might as well keep making the medicine, right?

Diane Wendt: Indeed. They were probably producing, like, half the penicillin, really, in the US, which would mean really the world.

Lizzie: Wow!

Diane Wendt: For some time. They were the big ones.

Lizzie: And in 1944, 16 years after Fleming discovered it in his lab, penicillin was finally ready for the battlefield.

Diane Wendt: They had enough by D-Day for the wounded on British and American soldiers.

Lizzie: Tiny glass vials of bright yellow powder traveled to medic bags and field hospitals across Europe and North Africa.

Lizzie: Oh my gosh!

Diane Wendt: These were some of the earliest ones. This is 44.

Lizzie: Like this one.

Lizzie: It's almost like—it's like a little test tube.

Diane Wendt: Yes. Well, this is an ampule, and it's a pretty common kind of drug container for anything that has to remain aseptic.

Lizzie: Inside is freeze-dried penicillin from 1944.

Lizzie: How did they get it out? It's like a sealed glass. Do they have to break the glass to use it?

Diane Wendt: You do have to break the glass to use it.

Lizzie: The powder could be sprinkled on a wound or mixed with liquid and injected. And as penicillin made its way to troops overseas, at home, a kind of penicillin-mania was taking hold. The drug was still in short supply, reserved for soldiers, but its miraculous powers were known far and wide.

Diane Wendt: This is actually an advertisement from a company that was making penicillin.

Lizzie: Diane shows me a full-page magazine ad from 1944 in Collier's Magazine. It shows an injured GI in a tropical forest with a medic kneeling, of him injecting something into his arm.

Diane Wendt: It says, "Thanks to penicillin, he will come home." And then down here, "From ordinary mold, the greatest healing agent of this war."

Lizzie: From ordinary mold!

Lizzie: This ad wasn't selling penicillin. It was basically just PR from one of the makers of it, Schenley Labs, basking in some of the good vibes surrounding this new medical marvel. And it wasn't just drug companies cashing in on the good press.

Diane Wendt: Everyone got on board in this story, if you can. This is from Crane Valves and Plumbing.

Lizzie: Diane holds up another magazine ad. This one shows the inside of an industrial penicillin plant, snaked with pipes and valves.

Diane Wendt: "Penicillin manufacturing depends on a good valve."

Lizzie: Oh, right. And pipes!

Diane Wendt: And good pipes.

Lizzie: [laughs]

Diane Wendt: The public saw a lot of this. It's just everywhere in the media. I mean, this is just the wonder drug.

Lizzie: While it's hard to measure the total impact of penicillin on the war ...

Kevin Brown: It's estimated that there was a third less mortality amongst casualties in the Second World War compared to the First World War.

Lizzie: Over 400,000 American soldiers died during World War II. But without penicillin, that could have been more than half a million fatalities.

Kevin Brown: The overall effect was both more people were surviving, but also there were less people with injuries and long-term disabilities.

Lizzie: But the world didn't forget Alexander Fleming, the lone bacteriologist who'd seen potential where others just saw mold. He became the ambassador for medicine. When the war ended, he was knighted by King George VI. He was invited all over the world to give lectures, and in at least one way he did appear transformed by his celebrity.

Kevin Brown: He was voted the best British council lecturer to visit Vienna.

Lizzie: What?

Lizzie: That means he beat out T.S. Eliot.

Kevin Brown: Fleming was the most popular.

Lizzie: Wow!

Kevin Brown: Now I think that was because he was somebody at this stage in his life people could relate to. Penicillin was a lifesaver, but Fleming was down to Earth, modest, unassuming, and it was a time when people were a bit sick of the larger-than-life figures of wartime.

Lizzie: And almost everywhere he went, he brought little medallions of the penicillin mold sealed in glass—a little keepsake like the one we have at the Smithsonian.

Diane Wendt: He would make these, and he would give them to a number of people. He gave them to royalty, to celebrities.

Kevin Brown: One to Churchill, one to Roosevelt. The Pope, even though Fleming wasn't a Catholic he still got one. Queen Elizabeth got about four. Prince Philip got two, and he said that when he was given the second one, he handed it to his equerry with the words, "Every time I meet this fellow Fleming, he gives me another of these bloody things!"

Lizzie: In 1945, Fleming, Florey and Chain were all awarded the Nobel Prize for their work on penicillin. But it wasn't all high-fives and chest bumps. In his speech, Fleming issued a surprisingly prescient warning.

[VOICE ACTOR: There may be a danger, though, in underdosage. The ignorant man may easily underdose himself and make microbes resistant.]

Lizzie: What doesn't kill bacteria does actually make it stronger. Fleming warned that overuse and improper use of antibiotics would lead to bacteria that was immune to penicillin. And what happened after the war proved that he was right to be worried.

Kevin Brown: Well unfortunately, Fleming's warnings about penicillin were ignored. People saw it as a miracle cure. It was the wonder drug of the age.

Lizzie: And the "wonder drug" was everywhere.

Kevin Brown: Antibiotics were being given out for anything.

Lizzie: Got a cut? Penicillin! Got a little cold? Try some penicillin! How about some penicillin toothpaste for that squeaky hygienic mouthfeel!

Kevin Brown: They were being abused, they were being misused. And the thing is, these are powerful weapons against infection, and should be used wisely.

Lizzie: Penicillin became so cheap it went into animal feed as a safeguard against illness in livestock. Then worked its way into food products. In the 1950s, cheesemakers started noticing that antibiotics in cow's milk were preventing milk from curdling in the usual way.

Kevin Brown: However, as long as new antibiotics were developed or existing ones could be modified, the problem could be kicked into the future. The thing is is we know only too well, the future is now.

Lizzie: By the 1960s, the term "superbug" had entered the national lexicon. MRSA outbreaks followed, and today antibiotic resistance is a global concern. It's hard to imagine in the age of gene editing that we could go back to dying from a skinned knee—but it's not impossible. Fleming warned us: use antibiotics wisely, or risk losing them.

Lizzie: The story of penicillin is often told as a medical miracle—and in many ways it was. But it's also a reminder that history is not inevitable. The mold could just as easily have stayed mold. It took one scientist to recognize the potential of this discovery, others to refine it, patients willing to be guinea pigs, governments investing in research, private companies shifting their entire business model, and citizens scrounging for mold.

Lizzie: The discovery of penicillin may have been accidental, but turning it into one of medicine's greatest achievements was very much a purposeful human endeavor.

***

Lizzie: You've been listening to Sidedoor, a podcast from the Smithsonian with support from PRX.

Lizzie: For some cool photos of the penicillin paraphernalia in the medical collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, check out our newsletter. Subscribe at SI.edu/Sidedoor.

Lizzie: For help with this episode, we want to thank Kevin Brown and Diane Wendt. Thanks also to Valeska Hilbig and Sam Robinson.

Lizzie: Our podcast is produced by James Morrison, and me, Lizzie Peabody. Executive producer is Ann Conanan. Our editorial team is Jess Sadeq and Sharon Bryant. Episode artwork is by Dave Leonard. Transcripts are done by Russell Gragg. Fact-checking by Nathalie Boyd. Extra support comes from PRX. Our show is mixed by Tarek Fouda. Our theme song and episode music are by Breakmaster Cylinder.

Lizzie: If you want to sponsor our show, please email sponsorship [at] prx [dot] org.

Lizzie: I'm your host, Lizzie Peabody. Thanks for listening.

***

Lizzie: "Let it remind you of how much Crane flow control has contributed to the American way of life." This is a good ad. I feel rather grateful.

Diane Wendt: Yeah! I'm gonna go get a good valve. [laughs]

Lizzie: I'm gonna go appreciate my faucet.

Diane Wendt: [laughs]

-30-