·S14 E10

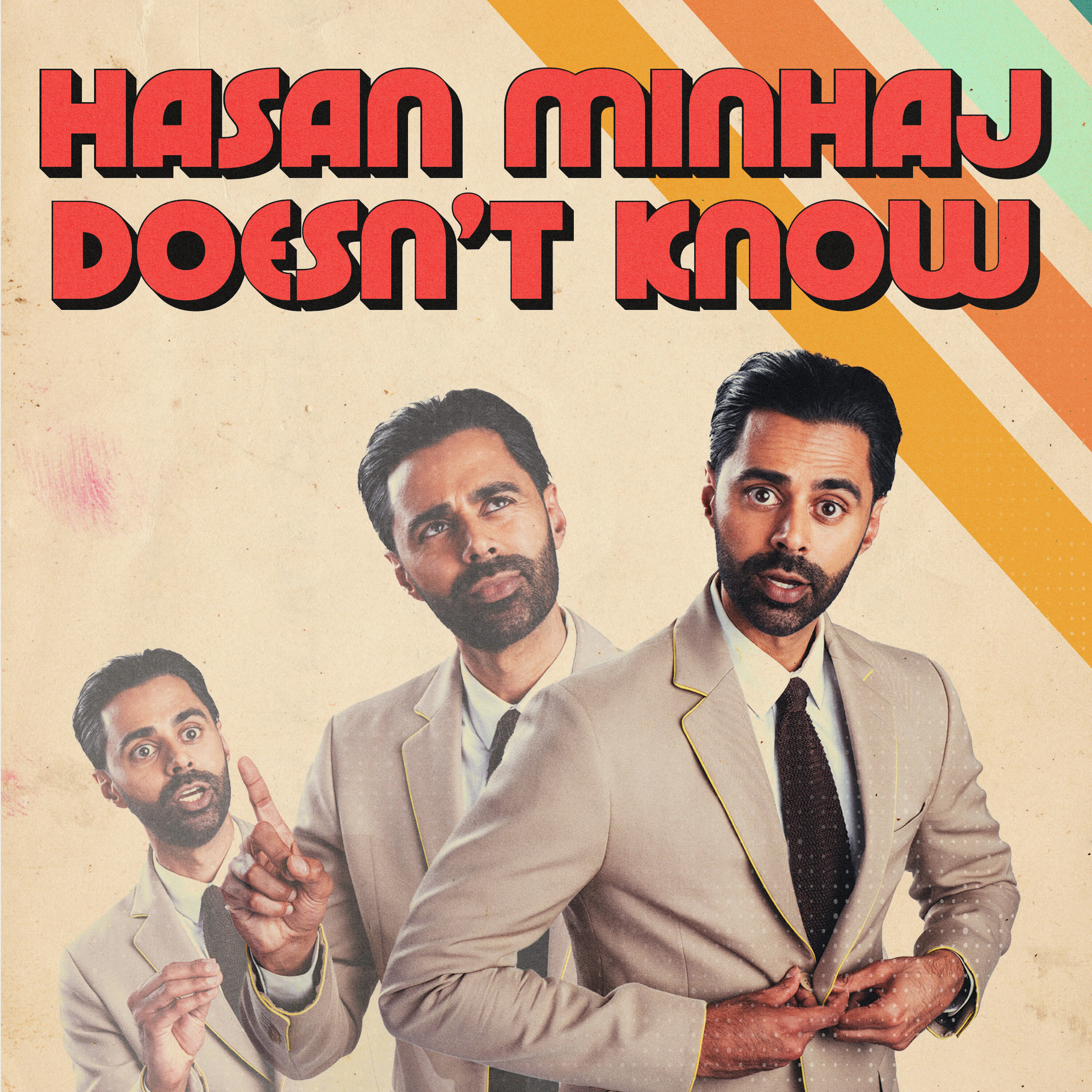

Malcolm Gladwell Doesn't Mind Being Wrong | From Hasan Minhaj Doesn't Know

Episode Transcript

Pushkin.

Hey everyone, I recently went on the podcast to one of my very favorite comedians Asan Minaj, and we had so much fun together, I thought we'd drop our conversation into the revisionist history feed.

My only regret is that we didn't talk more about basketball, since he's a fanatic and I'm kind of a phanatic too.

So have me back Asan and we can correct the oversight.

Here you go, enjoy the conversation.

Speaker 2Last thing, and I don't know if you got your pep and your step to do this, but you are very famous for giving people blurbs on the back of their book.

Oh yeah, Now, first things first, what is a blurb?

Because it sounds like a slur that you would hear in Harry Potter.

Speaker 1You bloody blurb two cents three cents endorsement goes on the back of a book which says I read it, I liked it.

You should read it too.

Speaker 3Do you mind giving a blurb for this interview?

Kim?

Speaker 1Oh my god, you're the master of blurb.

Speaker 3I've seen your blurbs on many different books at.

Speaker 1Niz Hassan got me to cry.

I wasn't expecting it.

I wasn't expecting that to happen.

Anyone who can make their guests cry deserves a shout out.

I would listen to Hassan doesn't Know on a regular basis from now on.

Speaker 3How are you prepared to be dazzled?

Speaker 1Pare to be dazzled?

Speaker 2Maybe no other writer epitomizes popular nonfiction like Malcolm Gladwell.

He literally made nonfiction popular.

Millions and millions of people have read his books, and that has gotten him in trouble with two groups, one snobs who hate popular things, and two people impacted by some of the ideas that Malcolm Gladwell helped make popular.

So I sat down with Malcolm to talk about the incredible new season of his podcast, Provisionist History and the profound impact that it had on him.

We shook me why his books have had such a wide appeal.

Speaker 1What my books do is allow you to play with the world of ideas.

Speaker 3And we get into his hot take on working from home.

Speaker 1I'll never live that one down.

Speaker 3I also asked him about that Blink cameo and White lotus.

Was it a compliment or a snake diss?

I mean, Mike White, what are you doing here?

Are you coming from?

My boy?

Speaker 2Malcolm, and more importantly, are you casting me in season four or what?

Because I am available?

Do you prefer writing books or do you prefer podcasting?

Speaker 1Well?

I like them both because it's so different.

It's like saying, do you prefer chicken to shrimp?

I mean, I like them both, but there are hard to compare because there's things you want to do with podcasting that you can't do with writing, and vice versa.

The thing I got tired of in writing books, I'm tired of it was too strong a word, but I wanted to get away from was I didn't like the insistence of my own voice.

So the thing that's lovely about podcasting is or the kind of narrative audio storytelling that I do, is that I get to recede and what I'm doing is collecting other people's voices.

Speaker 2I mean, your books have permeated culture in a way that is so It's so Hudson News Stand deep Like, there is not a year that I have traveled where I have not seen a Malcolm Gladwell book at an airport in the United States of America.

Did you see the cameo of Blink You on season one of White Lotus?

Speaker 3Oh?

Yes, how'd you feel about that?

Speaker 1That's hilarious.

Speaker 3Shane was reading it.

This is a moment.

Speaker 1I did love that.

I love that show.

Speaker 2How did you feel about the way Mike White described this moment?

So this is what Mike White said about it.

Blink just felt like such a Norman book.

It seems like he's stoking his curiosity, but it hasn't gone very deep.

Gladwell's the kind of writer that makes you feel smart while you're reading it, whether you are or aren't.

Speaker 1Oh, I love that.

That's a very sweet thing to say.

Speaker 3Don't you think some people think of this as a desk.

Speaker 1I don't think.

Speaker 2I see this as a compliment.

So he was writing that, like, that's why Shane is reading the book in it.

But I think I'm like, hey, you create egalitarian, accessible stories that people can read.

Speaker 1Yeah, and it's but it's I think if I maybe reading too deeply into that.

But the way I would phrase it is most people, as part of their daily lives, don't have a chance to engage in the world of ideas.

People's lives are full, they have kids, jobs, responsibilities.

They're not reading the Journal of the American Sociological Society at night right, or they're not getting exposed to the latest theory about this or that and the other.

There's no place for it.

They don't and so they don't get them.

They don't get a chance to quote unquote, if feeling smart means being able to play in the world of ideas, they have limited opportunities for that.

What my books do is allow you to play with the world of ideas.

I say, I'll go out and find cool ideas for you, arrange them, let you just indulge in them, see whether you like them, try them on for size, reject them if you want like.

And that's the thing.

The books have been successful because people have a They recognize the fact that once you leave college, you don't have easy access to right.

Speaker 2Right yeah, yeah, just hours and hours of kind of free, open, guided time to explore big ideas, explore big ideas.

Speaker 1I have the luxury of doing that for others, and that I think is a I think of that as a noble calling.

Speaker 2How do you feel when people put what you do on this huge pedestal that you go these Malcolm Gladwell books are these seminal books for intellectualism.

Speaker 3Do you feel like that's too big?

Speaker 2Of a title because I had this with with my Netflix show as well with Patriot Act.

People feel like these enfotainment shows are the same thing as being deep experts.

Like if you watch Patriot Act and you see our episode about fentanyl, you're not a fentanyl expert.

I'm not a fentanyl expert.

Like I'm literally reading off a prompter and I learned about this like a month and a half ago.

Speaker 1Yeah, I mean, I think I do think that's too much, But I think what to the extent that what people are doing when they say that is expressing their enthusiasm.

I'm happy because what they're what they're really saying is wow, I got to play in this world of ideas and it is way more fun than I thought.

That's cool, That's what they're saying.

Yeah, and they don't, and you're capturing that a moment in time, because usually what happens then is they feel emboldened to go on on their own and discover other stuff.

And so the moment when they think that, you know, Outliers, was the be all end all, it passes because they then start to discover on their own other ideas that complement their understanding of the world and they fall in love with some other thing.

I'm the gateway drug.

I'm not.

I'm not the addiction.

Speaker 2Is is your dream that it gets them on a path to being Like I need to access scientific research.

Speaker 1But I want to be the first thing.

I want to be the first thing you read, not the last thing you read on that subject.

Speaker 2I think one of your greatest gifts is probably your gift and ability to passionately tell a story.

I feel like you could tell a story literally about anything and get me engaged, Like could you do a revisionist history about W twos and W nine's.

Speaker 3Like how would you attack that?

Speaker 2Like give us a little bit of that Gladwell juice of Like how do you take these very mundane topics and make them super duper interesting.

Speaker 1You know, that's a tough one.

I have to look into it a little bit.

I've been doing this a version of this right now because I've been working on this project about American gun violence, and i want to tell a story about American gun violence and not talk about guns, not at all.

You got to talk about kinds of sumptions.

I'm interested in exploring all the all the peculiarities of the way America and think about gun violence that have that aren't the ones we normally think about.

And so there's one.

There's one where I do an entire chapter on the Second Amendment, which is all about this is the grammar of the Second Amendment and understanding in the eighteenth century if you wrote a sentence like that, which is it's a sentence that begins with an absolute clause and then has the operative clause, and the absolute clause is what's called it an initial being clause.

Particular kind of absolute clause, and initial being clauses loom really large in the grammar of the eighteenth century in a way they don't now.

And so the whole thing is all about eighteenth century grammar.

And it is like, I don't know if I pulled it off because no one else has read it.

It's a draft, no one else has read it.

Speaker 2But this, essentially, this is like a funk masterflex.

Can we get a bomb on this?

Can we get a bomb drop a hot ninety something bomb drop on this?

This could be the next this could be the exclusive, This is your jay Z hot ninety something, this, this is me, this is this could be the next book.

Speaker 1Well, this is a chap during the next book, Well.

Speaker 2Just drop a bomb on a flex.

Go ahead, did a bomb?

Just drop We're gonna do it in a post.

Speaker 1Okay, but it's possible.

I did not succeed in this, But I got so deep into eighteenth century grammar.

And what's interesting about it is that you realize the whole point of going on this incredibly nerdy grammatical path is to make you understand that when the Supreme Court passes opinions on the Second Amendment, they are making shit up.

They have no clue what they're talking about, and anyone who knows what they're talking about is like, oh my god, this is nuts.

To pass a ruling about gun rights based on our understanding of the Second Amendment requires it to interpret the Second Amendment because it's a sentence that actually makes no sense.

It's a pre modern sentence.

It's like not a sentence we'd ever write today, right, And they presume to interpret the sentence without knowing any thing about linguistics, in particular, without learning anything about historical linguistics.

That's ridiculous.

You can't read a sentence from seventeen eighty three or whatever it was in as as someone living in twenty twenty five and makes sense of it.

You've got to talk to people who knew what the way people phrase things.

In seventeen eighty three got it right.

And they didn't do that.

They just thought, oh, I can pull out Websters the Dictionary off the shelf and just tell you what the words mean.

Speaker 3This is.

Speaker 1If you did this for a paper in college, you would get a C minus.

Speaker 2You are very good at coining particular terms that catch like wildfire, tipping point for example, obviously your super popular book that came out in two thousand, Tipping Point.

I read it, many people read it.

What is it about certain terms that make them just catch on like wildfire?

Like I'll give an example.

Speaker 3You know the.

Speaker 2Term bucket list?

Okay, that term came from this movie.

There was a movie called The bucket List with Jack Nicholson and more startment with it starts with this.

Speaker 1It was not used.

Speaker 2It does not pre date this movie.

Yeah, like in social lexicon, it's not crazy.

But my question is is how do you know that something is going to catch like that?

Speaker 1You don't, I mean, how could you know?

I mean you can, you can.

It can sound good.

Speaker 2To you, but but picking a title is pretty big, like picking a title.

Speaker 3You know this.

Speaker 2You're sitting with this PDF, you're reviewing it, you're revising it.

It's like naming an album.

Speaker 3You go, okay, this is this is the phrase.

Speaker 1I mean.

I have a theory about what a title, what the perfect title is, although none of my books have ever had the perfect title.

The perfect title is a oxymoron.

So there has to be some tension between the two kind of operative words in the title.

So the famous environmental book for the sixties, Silent Spring, is to my mind, to perfect title.

Silent and spring are in opposition to each other, Right, it's an oxymoron.

No Spring is silent, and she's giving us she's that with two words, we instantly know that there's stakes, something has been right.

She's taken two very very very sure, familiar simple words, and by pairing them has just created this whole understanding of what's going on.

Right, So I've always That's what I've always strived for.

The title of my podcast, Revision's History is not quite that, but it's a it is.

The tension is that that term is something that's usually used as a term of disparagement, and so I am suggesting that something that's usually disparaging is actually worth listening to.

Speaker 2Can you help me coin some terms these things that I've been feeling.

As a comedian, I use comedy as a way to, in a healthy way, chance all my add and internal feelings into something that is useful and possibly provides people joy and comfort.

Can you help me come up with a term that describes the urge that men above forty have to want to engage in devour history, you know how, like dads who are forty four years old and they're like, I'm super into Ken Burns.

Now, what is that.

Speaker 1So true?

Speaker 2But yeah, yeah, the bad term I have is dad stalgia.

But that like that, it's not it's not singing.

It's not singing, baby, help me make it sing.

You know what I'm talking about.

Speaker 1I know exactly what you're talking about.

It never occurred to me till now.

It makes me happy that you have identified this thing and you're what's right about this is that it is absolutely the case that like there's a moment when they're all the species of dad.

It's like there's suddenly it's all about General Patton.

Speaker 2It's a species of dude.

Yes, it is a species of heterosexual man.

Speaker 1Second, war is all.

Speaker 2I'm going to keep giving you the exposition.

Hopefully this sparks something.

I'm talking about A type of guy.

See, here's what happens is in your childhood, your teens, your twenties, your thirties, you're like, how does the world work?

Okay, shit, that will hurt me?

Speaker 3All right?

Speaker 2What is a bank account?

Wells Fargo, got it?

This is a checkbook?

Checks are stupid.

This is a credit card, Holy shit, interest rates are high.

Finally got a job.

This is how you talk to people.

I think I'm awkward.

I should probably go to therapy.

You do all these things.

Then you come of a certain age and you're like, whoa, I kind of get the world and then you're like, how the fuck did we get here?

And then you dive into civil war by ken Burns, nineteen ninety.

Speaker 1That's right, it's like, but also it's about then that word what's that word?

Speaker 3Because it is.

Speaker 1You're also hearkening back to at the moment that you're beginning to lose your grip on your own masculinity kind of physical force, you're HARKing back to a time when those were the things that mattered the most.

Right, It's like it's like, you know, it's Testoster gone.

It's like it's I don't know what to it is, but that's part of it.

It is longing for not just longing for a lost era, but it's a longing for a lost version of yourself.

At the time when you could no longer be a soldier, you are starting to sort of indulge the stories and lives of soldiers.

Right.

You don't do it when you're twenty five because you realize, oh, that's me, like being slaughtered in the trenches or whatever.

But when you're forty five or fifty, it's safe.

It's like, oh, no, I wouldn't I wouldn't be called up if we went to war.

So now I can kind of I can stay home and watch Saving Private Rhine for the third time.

Speaker 2Sorry, I'm just like, I'm just still dwelling on Testospy.

Okay, let's move on to the next concept, because I don't want to dwell on this.

What I love about you is that you are willing to be proven wrong, and you talk about this in Revenge of the Tipping Point.

Dude, your Ted talk was nuts.

How did you feel about that Ted talk where you basically were like my bad.

Speaker 1I know.

The thing is, it's a flips that I was saying earlier because I don't have it.

Because I get such delight in personal delight in finding out that something I thought was one way is another.

It never occurs to me that there's any public cost to speaking about that out loud.

Right, It's like, it's fine, Like and if you're someone who likes my writing, you're used to that, and you're you understand that what the game we're playing here is we're playing in the world of ideas.

Ideas change, So we're gonna every now and again we're going to pull up states.

Speaker 2You know, I got to give you credit, man, It was really it's very cool of you to say, hey, I was wrong about this, yeah, and then also add that into the blockchain because we also live in a society where it's deny, deny, defend, deny, deny, deny die.

Speaker 1I don't understand this, because my understanding this is this, there's a whole series of cases where the perception of people at the kind of who have public roles and the perception of the rest of society are completely at odds.

I honestly don't think the average American is at all distressed to learn that an author whose books they've read would stand up and say, you know what, that twenty five years ago and I wrote about that change my mind.

I think I was wrong.

I think most people are like, oh, that's great.

You know why, because the common experience of most people in the world is that you have to change your mind all the time.

Anyone who's had kids, all you do is change your positions.

Used to be you're going to bed at seven, then all of a sudden at seven thirty and you're forced to confront the fact that the body of work that was devoted of parental work, that was devoted to seven PM as a bedtime, has gone out the window, and like there's no going back.

Yeah, that's it, right, So we're you like, but this there continues to be this perception among people in the public eye that if I do that, I'm somehow jeopardizing my credibility, which is so nonsensical to me.

Why wouldn't it jeopardize your credibility if you refuse to change your mind in the face of a rapidly changing world, Like that's credit that someone who's like saying the same thing today as they said twenty five years ago.

That is a threat to their credibility.

Speaker 2I think that is a byproduct of people saying, in certain particular circles, you cannot say you're sorry.

It will fuck up with your credibility.

That's because I think people have noticed some of the most powerful people on planet Earth are psychopaths that do not apologize, and we live in their ecosystem.

The shrapnel of their ideas affect us.

Yeah, Elon Musk, Donald Trump.

Speaker 3Et cetera.

Speaker 2Right, it's their ideas that they then push notification to the entire world, and we have to deal with it.

Speaker 1Yeah.

I interview these two people to the most impressive people I've ever met the other week Secretary of the Air Force and former Chief of Staff of the Air Force.

So Secretary is a political appointe.

Chief of staff runs the place.

They knew each other.

They were friends and when they were both running the Air Force.

There's a mass shooter I forget where Oklahoma goes in and kills twenty five people in like a church.

They get a call or in the morning that guy is an ex Air Force person, and then they get another call and by the way, he was drummed out of the Air Force dishonorably for committing some kind of act of violence involving a gun.

And it was your responsibility to notify the FBI so that he would be on a list that wouldn't allow him to buy a gun.

And you didn't do it right, Like shit, my institution screwed up, and as a result, this guy went out and killed twenty five people.

So they have a meeting, and everyone in the meeting, all the top brass in Washington there, tells them go slow, let's work the South.

There's maybe a weigh, some loopholes.

And they're like, no, we screwed up.

We're gonna just hold a press conference and say we screwed up.

And so they go, they say we screwed up.

They go towards Congress and they say, we blew it.

We made a mistake, Like we've got to have better.

We're going to find out all the people who are accountable.

We're going to fix this thing.

Speaker 2BA.

Speaker 1And then there's a funeral for some of the people killed by that shooter.

And the guy who's the chief of staff of the Air Force puts on his uniform, flies down to Texas, flies down to Texas and attends the funeral of the people who were killed because of ant of an air by his institution.

And I said to him, Jesus, did you what did you think was going to happen?

I didn't know what was going to happen, but it was my responsibility to go.

And I was so it was so anithetical to everything about the way public servants behave popular expectations in popular culture.

And it was two these two incredibly decent people who, by the way, they weren't personally responsible.

It wasn't like they personally didn't report it.

It was like something they run an organization with like one hundred thousand people.

But they took responsibility.

They took the heat before Congress.

And then the guy puts on his uniform and flies to Texas and goes to the funeral and goes up to the guy who just who was one guy there who lost six children, goes up and gives the guy a hug, right, just like And.

Speaker 2So you were blown away by the empathy, the humanity, and by the fact that he.

Speaker 1Didn't sure, he was not afraid to say I fucked up, right, And he said, at the end of the day, they were way better.

They were way better off for doing that.

Said when they went to for Congress, everyone was expecting them to deflect, deny, and delay.

And when he said no, no, we screwed up as the first thing out of his mouth, He's like they were completely shocked, right, And it's like sometimes the hardest thing is not just the best.

Speaker 2And maybe it's so refreshing because people and especially adults in corporate American in their day to day life, hear it.

Never hear that from those who are in power, from their manager all the way up to the sitting politician.

Speaker 1Or beer do Why is it?

I listened to that story and I was like, how can you listen to this story and still believe it's a good idea too?

Speaker 2I mean, this is such an inspiring thing that you're describing.

Just so our listeners are aware, Can you describe what you talked about in Revenge of the Tipping Point and in your ted talk in regards to the broken windows theory that you had in two thousand book.

Speaker 1In my twenty book twenty five years ago I made I was trying to describe why crime fell in New York City madically in the nineteen nineties, and I spent a lot of time arguing that it was the result of what was called broken windows policing, which was this idea that relatively trivial signs of disorder are sent a signal to would be criminals that behavior, misbehavior is possible.

More than that almost welcomed, right, no one's in charge.

That idea was then taken by the NAYPD, and that was the basis for the stopp and frisk program, where the NAPD went out and over the course of many years stopped hundreds of thousands of young black men on a street looking for weapons.

Because that was broken windows policing.

It's like, all right, if we crack down on gun carrying, we'll send a message that people will I At the time, like many people in New York thought that stop and frisk was a really good idea.

It's like, yeah, that's a good extension of this idea.

That's the way we keep the crime rate down.

A court stepped in and threw out as unconstitutional stop and frisk policing, and YPD went from stopping hundreds of millions of young black men every year to almost none.

And what happened, crime continued to fall.

So if you wrote it if you endorse stop and frisk, and then you were suddenly faced with the empirical reality that once stop and frisk went away, things did not get worse, but rather better.

You have to re examine your position, right, got it?

Wait, didn't work the way I thought it was going to work.

In my heart when I read that court case that throughout stopping frisk, I'm forgetten.

When it was two thousand and something, Like many New Yorkers, I was like, this is the end.

It's all coming back.

Speaker 3Oh you thought New York would turn into Gotham City.

Speaker 1Oh my god.

I thought the crime was coming back.

And so did.

I mean, if you read editorials in all the papers in New York and early aughts when that court decision went down, everybody was like glooming and dooming, We're bringing back the battle days.

Didn't happen.

The reverse happened.

Crime accelerate, the crime drop accelerated.

So I just gave a ted talk when my book came out, my last book, Criben's a tipping point where I talk about this, where I just said I was wrong, you know, and I have to take ownership of this.

And here's the thing that I have come to understand about that explanation I gave of why crime fell in New York I was wrong.

I wrote a book that was read by a ton of people, millions of people in two thousand, arguing that the way to explain New York City's crime drop was essentially some version of aggressive policing.

Speaker 2How did you feel when you found out that, oh, the NYPD used your book as literary or intellectual justification to stop in frisk.

Speaker 1I mean there were many I wasn't the sole source of there, but it was a biography, right, Yeah, but my book became part of this kind of zeitgeisty discussion, discussion about how aggressive policing was the way to cure crime.

I mean, if I think back to that time, I think I was flattered.

How could you not be, because we were in the middle of this extraordinary urban experiment where Neil goes from being one of the most dangerous big cities in the world to one of the safest.

And the idea that I was part of a movement that kind of helped justify this crackdown on crime was like made me feel good.

And then find out oops, at.

Speaker 2The end of the Ted talk, a woman comes on stage and thanks you for your mea Kalpa, And then you guys get into an interesting discussion about the way your work was interpreted for Did you.

Speaker 3Ever think about what if they got it wrong?

Speaker 1What if it was wrong and innocent people were going to have to experience this?

Speaker 3What were your thoughts about that back then?

Speaker 1Well, I wasn't thinking about that.

Speaker 3After that experien operience.

Speaker 2How do you now see your work in the way it's received by others?

Do you want to put addendums that hey, this could change or has it fundamentally how has it changed the way you approach your work?

Speaker 1Well, the over the course of my career, I think one of the changes that I've made is I have slowly come to the understanding that if you are going to play this game with ideas, you have to not temper your enthusiasm, but temper your certainty.

You have to make it clear that this is what we're talking about right now, and that ideas, by their very nature are based on evidence, and evidence changes, we learn more things.

Criminology is a great example.

Criminology last twenty five years, the feel of criminology has, I mean, so much has happened, We know so much more.

I mean, we were in retrospect primitives in two thousand.

We know like that one hundred years of advances and understanding have happened in the last twenty five years.

So we need to be remind people this is a knowledge is a moving target, and I think I need to do I've realized I need to do a better job of communicating that just because I'm saying this now doesn't mean it's going to be I'm going to be saying the same thing a generation now or five, or even next year.

Speaker 2By the way, by the way, hey, I've been caught in comedy crime before as well.

Yeah, as a drifting charlatan.

And I think the adjustment that I've made is you have to lead with.

Speaker 3I don't know.

Speaker 2That's what I make it very clear on our little microphones here, just in case if anyone is using micro content as a way or vessel to truth, I just want to make it very clear that the title of the show is awesome MANAJ doesn't know.

Speaker 1Don't get me started on what happened to you, which I'm still angry about.

Speaker 3No, don't.

Speaker 1Nothing is more tiresome than people who fact check stories.

These are not like you weren't writing a history of your life that was going to be published by Harvard University Press.

Speaker 3I was condensing many stories into seventy minutes.

Speaker 1That's you're a performer, forgetness sake, do we forget what a performer is like.

Part of what's funny about comedians, like the universe of good comedians, is that when we are listening to you, the thing that's that draws us to you is is the idea that you guys have a distorted lens like It's that's what we don't have.

We don't have a distorted lens.

We don't see the comic possibilities in looking at the world from a slightly different angle.

And the delight we get from listening is, Oh, that person's not looking at something straight on.

They have this completely you know this surprising wacko.

Never would have thought about it in a million years perspective.

That's the punchline.

That's what a punchline is, sure right.

So like to sit to fact check a story like that is to essentially undermine the very basis of what we want in a comedian.

And if you're getting your history from a from a from a comics routine, then you're so intellectually impoverished.

I have no time for you.

Speaker 2Welcome, don't do this already put out I put out a twenty three minute YouTube video about this.

Speaker 3You can see it in the way below.

But it's fine.

Speaker 1It drives me crazy.

Speaker 2So Malcolm, it's okay.

I'm a race baiting Britain Charlatan.

It's okay.

Speaker 3Meanwhile, you can you can.

Speaker 2And then you can make funny You can make funny jokes about it, and then you can sell out.

Speaker 1Any other people for who this stuff does matter get a pass, okay, Right, the politicians who are telling bullshit stories, they're not comedians, right.

I didn't vote for you to look at the world from a forty five degree angles.

Speaker 3Okay, Malcolm, you can put in comedy jail.

Speaker 1It's fine.

I guess that my sentence about this.

I do not want my comics to be like dryly relating the facts of the day.

Speaker 3Okay, understood.

Speaker 2You want your comics spicy, You want your comics line to you, and that's okay.

You know I got to give it to you, though, But again, you and I we love a hot take literally in your in you know you have revenge of the tipping point and then CBS Sunday Morning does a story on you.

Speaker 3And you've got even more spicy takes.

Let's take a look.

Speaker 1You should never go to the best institution you get into.

If you want to get a science and math degree, don't go to Harvard.

Speaker 3This is nuts.

Speaker 1Well, no, that's part of a complicated argument from my book David and Glythe which just says you should never if you're interested in succeeding in an educational institution, you never want to be in the bottom half of your class.

It's too hard, So you should go to Harvard.

If you think you can be in the top quarter of your class at Harvard, that's fine, but don't go there.

If you're going to be the bottom of a class, no doing stem.

You're just going to drop out.

You just get it.

Now.

Speaker 2You're triggering me because I was pre mad and I was in the bottom third of my class.

They did the whole thing.

Look to your right, look to your left.

Two of you won't make it.

Speaker 1You were one of those, was one of the two.

Speaker 2Yeah, and we don't have to get into this because you're triggering me.

But let me just say, Malcolm, if you do get into Harvard, you gotta go to Harvard.

Speaker 3You have to.

Speaker 1You know, if my daughters knock on Wood get into Harvard and I don't think they're going to be in the top third of their class, I'm gonna say, don't go.

It's too hard.

It's crazy hard.

Do you know how smart those kids are?

I know people who went to like elite public high schools, like you know Stuyvesant in New York.

Yeah, and everyone in Stuvesant basically has an IQ one hundred and eighty.

So the dumbest person in a math class in Stuyvesant can have an IQ of one hundred and whatever seventy.

So they think they're dumb because you measure your that's how you measure your intelligence by looking around the room.

They're not dumb.

They're in the top ninety nine point nine nine nine percent of humanity.

But they are misled by the fact that they happen to be in the most extraordinarily selective group of individuals in the city of New York.

Don't do that to yourself, or.

Speaker 2You should, because I'll tell you why both Ted Cruise.

Ted Cruse went to Harvard and then Donald Trump went to Penn.

So my point is is that there are idiots that go to these institutions and if they can spin it into a win, so can you.

If you get into Harvard, go take your shot of going to the league, if you get drafted, if David Starting gives you the call.

I went to UC Davis, unfortunately.

And the crazy part is I got into UCLA, but I didn't go I went to Davis instead.

Speaker 3This is a longer story for another time.

I got scared.

Speaker 1Your family's from Sacramento.

Speaker 3With it, Sacramento Davis.

I grew up in Davis and I went to UC Davis.

Speaker 1You got you do want to go to you?

Speaker 2I met I met my wife there and so so it was the biggest bles all and it was wonderful.

Speaker 1But you see Subercamp, It's.

Speaker 3Like, Malcolm, I get it.

Speaker 1What were you doing?

Speaker 3I know, I know, I got I got shook, I got shund That is madness that I didn't go to UCLA.

Yeah, I know, I know.

It is a regret.

Speaker 1Were you like an agg major?

Like what were you is?

Speaker 3This is a pre major?

Speaker 2And I ran into somebody when I did my campus visit that said, hey, stem at UCLA is really hard.

Speaker 3You shouldn't go here.

Speaker 1Oh, I see, so you're thinking, and.

Speaker 2That's what got me to not go.

Now, look again, I met the love of my life, the mother of my children.

Speaker 3At UC Davis.

Let's take that reality to the side.

Speaker 2Everything else.

UCLA the wooden center of the history Kareem abdul Jabbar.

Speaker 3And you're in the middle of last would I should have gone?

Speaker 2And so, Malcolm, if you get a call from Adam Silver that says we're calling you up to be one of the four hundred players to play in the league, you got to go to the league.

And if you can't cut it, fine, but you got to go to the l Let's look at another one of your crazy, spicy takes that I don't know how you thought this was cool.

Speaker 3Let's take a look.

Speaker 1It's not in your best interest to work at home.

I know it's a hassle come to the office.

But like you know, if you work, if you're just sitting in your pajamas in your bedroom, is that the work life you want to live?

Speaker 3Is that the work life I want?

Answer?

Speaker 1Yes, so much trouble for that.

I'll never leave that one down.

I can't believe you dredge that one up.

Speaker 3It's one of the top videos of you, Malcolm, What am I wearing?

You're wearing like a great tea shirt.

Speaker 2So the irony here is that you're telling people to not be bums being their pajamas and work at home, and you're wearing a goddamn Haines tea Here.

Speaker 1Here's what I should have said.

I should have said two things, No, one thing.

It depends who you are.

If you're twenty five and you're trying to entering a new field and trying to master it, you shouldn't be at home.

You got to go to the office because you got to learn from other people.

And it's way, way, way, way easier to learn from other people when you can see them face to face.

If you're fifty and you got three kids at home, and you've got an hour and a half commute, and you're really good at your job and experienced, why are you coming in that makes any sense?

You can be way more productive at home.

Depends who you are.

What I was reacting to, I think in that was this widespread belief that every is better off just working from home.

I don't think that's true.

I do think if I had worked from home in my twenties, I would not be here.

You would never have heard of Malcolm Level.

Speaker 2Here's my subway take.

I'm kareem now I have one hundred percent disagree.

I'm not here to tell anybody how they should live their life.

I used to work at Office Max for many years.

I'm not trying to brag, but I wasn't a great employee, and I truly did not care because my first name isn't Office and my last name isn't Max.

Whatever you can to do, you protect your own, get the bag and take care of your family, do your thing.

Speaker 1Yeah, no, that yours is a bunch more evolved position than mine, but I do.

I was simply trying to explain if you've never if you're young and you're trying to, like I said, master something complicated, it can be hard to understand how much richer the learning experience is when it's in a social setting, right, that's all, if you're trying to be a journalist.

So when I started out in journal I got a job at the age of twenty three at the Washington Post, and I was within ten feet of four or five of the greatest journalists of my generation.

And I didn't know any about journalism.

Speaker 3And I whorr you around?

I mean, man, I.

Speaker 1Mean, among others, Bob Woodward was greatest investigative reporter of the twentieth century.

Was as far away from me as you aren't.

There was just a serious a guy named Steve call who was like a legend.

There was a guy next to me called Mike Kisikoff who was another legend.

And I spent like six months, my first six months, almost doing nothing but sitting there and just eavesdropping and like it was a masterclass all these things that I didn't know.

Idea, how to ask a question, how to get how to interview someone who didn't want to be interviewed, how to frame idea, how to extreme I could go on and on and on, how to process things on the fly, how to write.

I just watched them.

Speaker 3You picked up a ton of game from these people in person.

Speaker 1And No, by the way, no athlete would ever say you can master a sport by yourself.

Every would They would never say, oh, I got drafted by the Nickson.

Here's what I'm going to do to work from home over the off season.

No, they would never say that.

Like, no, if Lebron wants to spend the off season by himself.

Absolutely, he's the top of this game.

But if you're a rookie, if you're nineteen and you just got drafted out of wherever, Kansas State, No, you show up with your peers and learn from them.

That's what That's all I was saying.

I don't think that's a I do not think that it's a controversial take.

And I was speaking from my own personal experience because I had become aware, acutely aware, in later life just how much I learned in those early years in journalists.

Speaker 2You know, Malcolm, you were able to pick up game from some legends at some great institutions.

Speaker 3But a lot of people who have jobs.

Speaker 2Their coworkers are a bunch of bums, and so they just want to say, peace out, Carl, Yeah, I'm going home.

Speaker 1I don't know.

You're more of a cynic than me on this.

I actually think that if you're if you are motivated, you can always find in any setting somebody from whom you can learn.

And that's part of That's another thing that is useful about going in your early years, in going to the immersing yourself is making those kinds of social calls, right, there's ten people around here, who's the one that matters and that I should be attaching myself and learning from.

That's a really, really important skill that you can't learn by yourself.

Speaker 2We've had an amazing conversation, but we haven't even gotten to I think one of your best pieces of work.

I'm talking about the podcast revision Is History.

Yeah, Season eleven, Ladies and Gentlemen.

Season eleven of Revisionist History is about the Alabama murders.

Now that's the title of it, But give give me the details of what launched this story about this particular situation in Alabama.

Speaker 1A friend of myn named Stephen I was talking to about a year and a half ago when he goes, I have a friend named Kate who has the most interesting job in America.

You should talk to her.

I was like, okay, And I did this thing which I've started to do more and more and more, where I find someone interesting and I just sit down with them for as many hours as they can tolerate and just talk to them with no agenda.

So Kate was someone.

Kate Porterfield was this really extraordinary woman whose job it was She's a trauma expert, and she started out by treating people who've been started working at the Torture Clinic of Bellevue, treating people who've been tortured around the world.

I'm this world renowned torture clinic there.

Then she went on and she spent a lot of time on Goodtnama Bay working with people who've been tortured by the CIA.

And then she got involved in criminal cases, capital cases where she was brought in by usually by the defense in a death penalty case to try and understand the life and the trauma of the convicted killer.

Right and so incredibly interesting.

So I sat down with her.

We met five times, each time for about three hours, and in the fourth time, fourth visit, fourth session, she started talking about a case she had just finished working on by a guy named Kenny Smith, and I was just floored.

I was like, Oh, my god, that's what I want.

So in our like twenty I was like, Oh, that's what I want to talk about.

Speaker 3Yes.

Speaker 1Kenny Smith was a guy from Florence, Alabama, in the north western corner of the state, who had been convicted in nineteen eighty eight of murdering the wife of a preacher, and it was a murder for hire.

And I'd been sentenced to to death by in a state of Alabama, and I'd been living on death row for forty eight years.

And she got involved in that case as just as Kenny was about to be executed, and so I just said, oh, I wonder to tell that story.

And it is the most I think it's the best thing I've ever done.

It was the most emotionally powerful thing I've ever done.

We ended up doing seven episodes, We ended up expanding it, so Kate, who plays a central role in the story, doesn't even appear until episode five or six.

Speaker 3Isn't it.

Speaker 2It was two men that were two men, Yeah, another guys as well.

So the whole premise of this thing is so interesting.

It almost sounds like a prestige show for FX, which is there's a wife, there's a husband, there's a murder for hire.

The men assault and beats said wife, but then the husband kills the wife.

Speaker 3We think, we think yeah, And then.

Speaker 2It's specifically about the two men that were part of this murder for hire that are then given the death sentence.

And what's really fascinating about it is you think this is almost like true crime, but it's actually an analysis about how crazy Alabama judges are.

Speaker 3Why are they so crazy?

Speaker 1Well, why is Alabama crazy?

I mean, Alabama is the weirdest stay in the Union.

Speaker 3I think that's.

Speaker 1Beyond dispute, also one of the most fascinating.

I mean I say that I actually love Alabama.

I go there.

I've done so many stories there.

I go there all the time.

I find it absolutely riveting place.

The great curse of the United States is of course, to the legacy of slavery, which has persisted.

That curse has lingered longer in some parts of the country than others, and Alabama is a place that is still kind of struggling under the weight of that legacy.

Now, this case involves everyone's white and in this case, so it's not explicitly about the relationship being black and white people.

But what we're describing is a brutal and unfeeling system of punishment that arises in response to the kind of racial realities of the state.

So we have this what we're documenting in this series is the unrelenting, tireless, relentless desire on the part of the state of Alabama to find a way to murder these two guys, to execute these two convicted murderers.

Speaker 2What's so interesting about it is this is an analysis on capital punishment.

So the jury is actually against the death sentence, the judge is for it.

But just for our audience before they dive into the season, can you give me the history of capital punishment in America?

What's the history of capital punishment in the United States.

Speaker 1Yes, so it's compared to our Western European peers, America was very slow to kind of dial back capital punishment.

It's a pretty big deal in this country up through the seventies.

And then the Supreme Court says, We've looked at the way capital punishment is being used in the States and we think it clearly shows signs of racial bias and arbitrary in US.

You know, you get two people convicted of the same crime, one's getting executed one tonight.

You can't do that.

You got to have some kind of rigor.

They put a pause on it on death pedally.

Public support for the death penalty plummets and people think it's going away, and then it comes roaring back, not everywhere, but particularly in the South.

And one of the states in which it comes running back is Alabama.

And Alabama does this thing to ensure that they will to retain their right to execute whoever they choose.

They give the judges what are called what is called override.

So the only one of the state in the Union that does any remotely like this.

But in the state of Alabama, if you are convicted of a crime and the jury votes for life without parole and not the death penalty, if the judge wants it's not been change but for many years, if the judge wanted to, the judge could override the jury and just say, I know you wanted life without parole, but I think this person should be killed.

And which is like a really really weird thing where they basically throw out.

Speaker 2A judge basically gets to have a super veto on a jury, which is nuts nuts.

But have two questions follow up questions.

The first is is that up until the seventies they were like, no, we cannot kill people, we are against the death penalty.

What was it about the Supreme Court that lifted that band?

Speaker 1So everyone's doing it.

The Supreme Court says stop, and then the sweep got comes back a couple of years later and says, you can proceed so long as you ensure they're speaking to the states that there's some rigord of the process.

You gonna have standards you have to say, you know what.

Speaker 3Other standards here.

Speaker 2They're like, look, you can't the guillotines gotta go, we can't have a firing squad.

Some states, by the way, have the firing squad.

Speaker 1Right, Yeah, there's a big week.

I didn't get into it, but I interviewed all these people about you know, one of the standards is the method of punishment must be neither cruel nor unusual.

And so you get into these big definitional things.

Is is lethal injection, for example, cruel And there's a big argument that it is because you suffer.

Actually you think you're not suffering lethal injection, you are, Then the electric chair was clearly cruel.

You did suffer.

So there's a big argument.

One of the reasons that UTAH brings back the firing squad is that as an argument that it's more humane than lethal injection.

Actually, if I had to be executed, I would choose the firing squad over lethal injection.

Speaker 3It's that bad lethal injection.

Speaker 1Yeah, we talked about that in one of the episodes.

Speaker 3So take me through the mechanics of lethal injection.

How does it work?

Speaker 1It's three drugs.

It was dreamt up by this doctor in Oklahoma in the seventies on the back of an envelope.

It's never been subjected to any kind of scientific protocol or medical analysis.

Is the random dude in response to a request from the Oklahoma state legislature which wanted to start putting prisoners down the same way they put down horses.

And so the guy says, Okay, here's what you should do.

Give them a sedative like a barbituate, then hit them with a paralytic that basically kind of freezes you.

Yeah, and then hit them with potassium chloride, which will stop their heart.

I think basically this position is that should work.

I was like, Okay, let's do that.

Speaker 3And Reagan, funny enough, was a big proponent of.

Speaker 1Reg's proponent of it, and so lethal injection which spreads throughout America and then throughout the world.

So you know in many countries now that have euthanasia legalized euthanasia, they're using the lethal injection protocol.

Well, we have a whole episode of the podcast where this really brilliant anaesesiologist from Orlando named Joel Zivitt Barry does all these autopsies of people who have been executed.

He finds that their lungs are filled with blood, frothy blood, and realizes what's happening is that the barbituate that they get at the very beginning is given in such a high dose that it's turned their blood as acidic and it's burning up their lungs.

So what happens is your lungs are on fire, which is, as you can imagine, quite painful because you've been giving a paralytic you can't cry out in pain.

Speaker 2I mean, the way you describe it in the podcast is horrifying.

This is the poll quote.

The last thing that you may know is that you're on fire from the inside and the blood is filling up your lungs as you die.

Speaker 1It's nasty.

The whole point of this is no one who's involved in the death penalty game is even remotely interested in trying to prove that this is a quote unquote humane method of They don't you when Joel Zivitt did the analysis of autopsies to figure out what was going on with lethal injection.

Lethal injection have been used in American prisons for close to fifty years.

So for half a century we've been doing this, and no one bothered in fifty years to ask the question of how exactly lethal injection was doing its work.

That's the level of kind of moral callousness that we're talking about.

Speaker 2It just felt like it was common knowledge when Reagan was like, look, they use it on horses, but now horses are people, so it'll be the same.

Speaker 1Yeah, And we go into this in some detail, and it's the most horrifying part of what is a very long and horrifying story.

It's just like nobody gives a shit.

Speaker 2Well, there's an interesting philosophical discussion to be had here with I call them the revenge heads, the petty police.

Speaker 3There's two camps.

There's one camp.

Speaker 2That's like, there has to be a more humane way to have justice and to understand that you cannot just kill human beings.

Then there are people that are like good, yeah, good.

Speaker 1There's a lot of that.

Speaker 3No, but for real yeah good yeah.

Speaker 1There is that strong which I don't understand.

Speaker 3How do you react to that sentiment?

Speaker 1It seems peculiarly American, it seems peculiarly medieval.

It's part of this weird thing about this country.

Which is that we are simultaneously the most sophisticated country in the world and also the least.

The larger part of it about this is that if you compare the US to say, Western Europe or parts of South Asia East Asia, that we're very interested in the severity of punishment and they're interested in the certainty of punishment.

So if you think about deterrence, about the attempt to dissuade someone from committing a crime, the certainty of punishment, how likely are you to get caught, the severity of punishment, how much you'll suffer if once we catch you, and the celerity of punishment, how quickly it happens.

In Europe, they are super focused on certainty.

If you murder someone in Europe, it's almost one hundred percent certain you will get arrested or someone will get arrested for that.

Homicide certainly super high, but they go really easy on severity.

Prison sentences are fractions a long.

Most people don't go to prison.

We do the opposite.

We have very low certainty the chances of getting arrested for homicide in this country, or less than fifty percent in parts in certain neighborhoods in this country.

They're beholo on the South side of Chicago, it's like fifteen percent.

But if you get caught, you will throw away the key.

Right, So this is part of that same dynamic.

We've decided we're going to put all of our eggs in the severity basket and make we want to make punishment as horrifying as it sounds to try and dissuade you from committing a crime.

The Europeans said, that's don't put your emphasis there, put your emphasis on certainty.

I happen to believe the European approach is far superior.

Speaker 2Why do you think in America there is this obsession, particularly with the severity and the feeling of hey, look, if you kill these bad people.

We're talking about criminals, we're talking about murderers.

If you kill them, now you just have good people left.

Yeah, that was kind of the conversation I had I had with different friends and people at the office before you came in, Hey, how do you feel about this?

And there was again camp of people that were like, this is barbaric.

All of this is barbaric.

The Green Mile electric chair is barbaric.

Yeah, firing squad is barbaric.

Lethal injection.

This is nuts, it's all crazy.

Speaker 3I'm not with this.

And then there's people that are like, yeah, it'd be like.

Speaker 1Mind, this is a total digression.

But my brother was a principle in an elementary school and he was his great struggle was ensuring the quality of his teachers, right, because it's a big difference.

And he would always say, you cannot fire your way to a better school, meaning that like you think your first thought is, oh, I'll just get rid of my bad teachers and hire good ones, and he's like, doesn't worked that way.

You can't you If you're just getting rid of the bad ones and quote unquote hiring good ones, you're not solving the problem that made the bad teacher bad.

Right.

You have to look at yourself and say, am I developing people properly?

Am I supporting them properly?

Am I putting them in the right place?

Those are the questions you got to start with.

You can't just like go in there and willingly get rid of me people.

And I think there's a version of that with that's what's not happening in people who are obsessed with killing off murderers.

They aren't asking the harder question which is, well, it doesn't help.

You're just going to if you don't solve the underlying conditions that create this, you're just going to get another crop taken your place.

Speaker 2You have obviously a high level of empathy and curiosity, and one of the ways that you showed that is the way you end season eleven.

There's this really powerful moment where you speak to the therapist of the man who was sentenced to death, and you do something that is extremely rare in podcasting.

You literally are quiet and choked up and silent for a minute.

Speaker 3Now.

Speaker 2Remember this is a medium where you have to keep yapping, but you are so emotionally moved that you cannot even speak.

Why did you choose to end the podcast in this moment?

Speaker 1Because we've been on this, I'm going to get an emotion about it all over again.

That doing that show was the single most There are a very small number of events that I've been a part of in my life experiences that have shaken me emotionally.

Death of my father number one by far.

I'll never get over that, birth of my children in a positive sense, doing that show is like up there in the shook me, shook me and still does it was incredibly hard to write, to report to like the number of times I found myself after a conducting interview where I couldn't function for the next like, and it seemed the most honest thing to do at the end of the show to communicate the fact that this tore me apart, right like, because what I wanted to do was the whole idea was it was a show about people who looked at these two kids from this little town in northern Alabama who do something insanely stupid when they're nineteen years old and were written off by the state of Alabama and by the rest of society, and the series of people come and see in them some element of humanity, go to the trouble of investing in these kids whose society has thought were worthless and finding something of value in them and learning how to love them, right And I mean, in one case, this guy we talked about, I think episode three, this lawyer visited this guy in prison, drove two hours each way once a month for twenty years to visit this kid in prison, one of one of the murderers in prison, just to spend time with them, and that like, just throw me apart, right I just it just and I needed at the end of that of the of the show to kind of just to tell people that, like, it's okay to like, it's okay to to it, it's okay to feel it is okay to open your heart to someone whose society, to someone whose society's given up.

Speaker 3Thank you for sharing that.

Appreciate it.

Man, It's a very powerful moment and something to think about.

And it's a very.

Speaker 2What I thought was so amazing about It is a very real thing that there are people.

These two men obviously did something wrong, but for you to explore the complexity of despite the fact that people make mistakes and do things that are horrible, we're still human beings and we're some much more than what the state was thinking, where they would literally kill people from the inside as if they were animals.

Yeah, and so I just thought that was a really powerful moment, And thank you for sharing how those interviews moved you.

Speaker 1Yeah.

Speaker 2Do you hope that it makes us as a society more empathetic or it makes perhaps America reflect on our own internal empathy.

Speaker 1It's always it's always a hope with these things, you know, it's very difficult to measure the impact.

But I think all you can do is, like is just join the chorus right of people who are are insisting that we be more human.

Speaker 2I gotta somehow end on a positive note.

We got a button this thing?

Speaker 3How do we do?

Speaker 1I don't know what I did bring us down to, not my ability to kind of like inject a down or note to any room.

Speaker 3I appreciate it.

Speaker 1I was.

Speaker 2It was a rare podcast moment and I think an amazing counterweight to the never ending blabbering that we have through laugh mics.

Speaker 3It was just a really human, beautiful moment.

Speaker 2And so, like I said, everyone, please listen to season eleven of Revisionist History.

Speaker 3Last thing.

Speaker 2And I don't know if you you got your pep and your step to do this, but you are very famous for giving people blurbs on.

Speaker 3The back of their book.

Speaker 2Oh yeah, Now, first things first, what is a blurb?

Because it sounds like a slur that you hear, Harry Potter, you bloody blurb?

Speaker 1Two?

Speaker 3What is it?

Speaker 1Two cents?

Three cents?

Endorsement goes on the back of a book which says I read it, I liked it.

You should read it too.

Speaker 3Do you mind giving a blurb for this interview here you can.

Speaker 1Oh my god, you're the master of blurb.

Speaker 3I've seen your blurbs on many different books.

Speaker 1At Hassan got me to cry.

I wasn't expecting it.

I expecting that to happen.

Anyone who can make their guests scry deserves a shout out.

I would listen to Hassan doesn't know on a regular basis from now on, how.

Speaker 3Are you prepare to be dazzled?

Speaker 1Prepared to be dazzled?

Speaker 2Can you also ad a parenthesis that I didn't bully you into crying?

Speaker 3Holy rne away only lay No.

Speaker 2If you haven't subscribed to Lemonada Premium yet, now's the perfect time because guess what.

You can listen completely ad free.

Plus you'll unlock exclusive bonus content like Halle Berry on how to be a good partner during menopause or Maddie Husson on the dumbing down of media clips you won't hear anywhere else.

Just tap that subscribe button on Apple Podcasts, or head to Lemonade Premium dot com to subscribe on any other app that's Lemonada Premium dot Com.

Speaker 3Don't miss out