·S8 E13

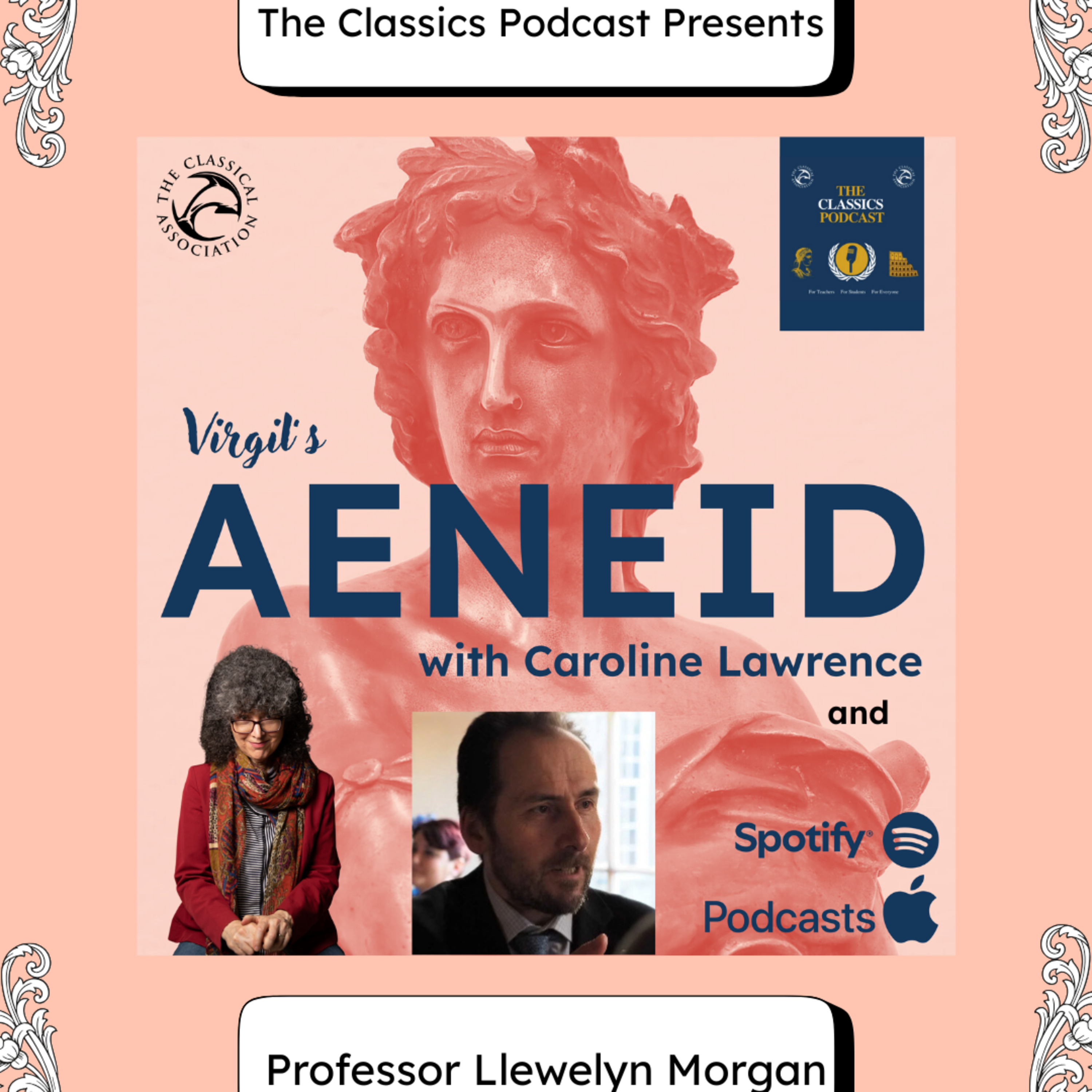

Virgil's Aeneid: BONUS with Prof. Llewelyn Morgan

Episode Transcript

Hello and welcome back to the Classics podcast.

Does Virgils Aeneid with myself Katrina Kelly?

And me, Caroline, Laura.

And welcome, we may have lied in our last episode when we told you that this was the end of the series.

We're back because we have a very special episode for you with a very special guest.

And it is the one and only Professor Llewellyn Morgan.

He's professor of classical languages at the University of Oxford, and he's a fellow with Braes Nose College.

And I know that, Caroline, you're a bit of a Llewellyn fan, aren't you?

You can see by the big grin on my face and the fact that I'm wiping away tears of joy, I'm.

A huge Caroline Lawrence fan too, you know, so this is 11 we're talking about, but.

We are so thrilled and what we're going to do is we're going to ask all the questions that we've been dying to ask and that many of your pupils have probably wanted to ask but maybe not had the courage.

But also it's going to be Virgil centred.

But also a little bit.

You said a bit.

First of all, do your friends call you Llewellyn or Lou?

If I had any friends, Llewellyn normally at Slovelen, if they really were, if they really really into my friends.

But no, Llewellyn is fun, yeah.

OK, so we're going to dive straight in and I, I've been loving your lectures on Massalet.

Little unsolicited plug there because I obviously did not go to Oxford.

So it's a wonderful chance to see great lectures and you are inspirational.

It's just been fantastic listening to your lectures and your love of Virgil comes through so clearly.

And I just wondered, one of my first questions is you've been learning and teaching Virgil for almost your whole life.

Do you remember the first passage that you read and loved and kind of?

I absolutely do.

I don't know whether you have this experience of being much more able to remember stuff that you read when you're about sort of 1516 than than stuff you read 2 days ago.

So, yeah, what I remember very vividly, apart from chunks of Chaucer and and and Shakespeare and stuff is the moment in book two of the Inaid where Inaus is asleep and is about well, and then Hector appears to him in in a dream.

So, you know, tempus erat Co prima queas mortalibus igreis incapit and and so on.

And I remember that because it's it was where my O level Latin prescription started.

I was very lucky I was able to study Latin at at school.

And I think what's most interesting about that is that over time, you know, over studying Virgil for, you know, for my entire life really, I've understood how much richer that passage is in in implications than I'd appreciated at the time.

But the beauty of the poetry I could see, you know, back then.

Fantastic.

What a great answer.

Thank you.

Katrina, do you want to do the next question?

Well, I do it follows on because you say that you've interpreted that passage, you've understood more depth and meaning to it as time's gone on, but have other passages kind of really risen to the fore and and become the one that you love the most?

Has has your feelings changed on that or is Book 2 always something that you go back to?

I.

Mean that is a good question.

I think what I've appreciated I did more and more over time is that Virgil's according to Virgil's plan, the second-half of the poem is much more important than the first half of the the poem.

The second-half of the poem is you know where we really crack on and and and and and set about founding Rome.

I mean, one passage that I, I would, I've thought of, thought about a lot because I'm very interested in Hercules as a mythological figure and specifically Hercules in the innate.

And he's a, he's not a major figure in the innate, but he kind of bubbles along in the, in the background as a kind of model for, for innate.

And there's a really remarkable, I think, passage in in book 10 palace, the young warrior is about to fight Turnus.

And as he sort of moves towards Turnus, he prays to Hercules because Hercules had visited him and his father in in Rome.

We'd heard about that in, in Book 8.

Hercules in the in the interim has become a God, having been a hero who's become a God.

And he's there in heaven and he hears palace praying to him.

And Hercules weeps.

And this is a big deal because Hercules doesn't weep.

Notoriously, gods absolutely don't weep.

But Hercules is both a new God.

He's learning how to be a God.

So he hasn't quite touched it yet, but also it tells you how post this relationship is with with palace that he's weeping.

But then we we hear from Jupiter who says, come on, Hercules, we're gods.

These are heroes, mortals.

They they die.

And Jupiter is essentially sort of teaching Hercules the proper attitude of a God to to mortal mortal suffering.

You know, this passage is about 25 lines long or something.

So much going on there.

It's, it's not, it's not true.

That links in with our Potter episode, doesn't it, Katrina, because we I was talking about that wonderful book Fathers and Sons in the Aeneid by Owen Lee or whatever his name is, and the subtitle is Sick Geni Tornatis.

Thus the father to the son.

I I gave our listeners the clue which father is saying this to which son?

Yes, Jupiter to Heracles, isn't it?

Yes, that's right.

According to certain versions of the myth, Hercules, Heracles is the father of palace.

So it's it's a moment where you could say that the kind of assimilation of Aeneas and Hercules is very strong, but also that that Virgil is kind of exploiting alternative versions of the myth that his his readers knew about.

We can.

We can get glimpses of that.

And it's also fascinating that Aeneas is often a Hercules like character because he's often wearing a lion skin or sitting on a lion skin or riding on a lion skin.

It's that lion skin motif going all the way through.

And when I wrote my book from the point of view of a dog who would smell things, he's always smelling lion skin on his.

No, that's right.

And and the lion skin is over his shoulders typically.

And the shoulders are the sort of characteristic body part of a hero because with the shoulders you you undertake labours or undertake responsibilities.

And of course it's when he has the lion's skin on that he picks up his father on his shoulders and takes him out of Rome symbolically kind of taking Troy with him or taking the past with him.

So the imagery is really kind of interesting.

Yeah, that imagery is is separate.

Katrina, what do you want to say?

Yeah, You mentioned Hercules weeping and we talked, we had an episode where we talked about tears.

Lacrimi and I wondered what your thoughts are on Virgil's own kind of views around what this means for for male heroes in the story around weeping.

And when we think about Augustus as well.

And to him is that message of you know what?

What does being a man mean to the Roman audience?

Well, I think in general in the, in the, I mean particularly well, no, actually throughout, I mean, you're encouraged to expect Aeneas to be a pretty stereotypical Roman ideal, ideal Roman male.

Let's let's put it this way.

When, when he shows emotion, in particular when he's experiencing gun of affection for, for Dido in, in, in, in Carthage, we're sort of sort of encouraged to see that as a distraction from, from, from what he should be sort of concerned with.

I mean, it's, it's more complicated than that.

We're meant to feel sympathy for both of those characters, I think.

But ultimately he must go and, and found Rome.

It's typical of Virgil, though, And, you know, we, we may well get back to this.

He makes us aware of what the consequences are of everything that is being achieved in this poem, everything that Ennius is achieving and and deeply aware of the tragic consequences of much that happens.

So there's much room for tears.

If Hercules is crying, that's a big deal.

I mean, Hercules does not cry.

You certainly shouldn't cry as a God.

As I've said, he's crying because why is Palace die?

Why does Palace need to to die?

It's a question that Virgil insists on us contemplating and and finding challenging, I think.

One thing we noticed reading through is that I counted the times and he is cries it's least 8 or 9 times but always from emotional pain and when he's got the arrow in his thigh then he doesn't cry physical.

The hero doesn't cry but their Achilles cry.

This is weep, so I think heroes are allowed to weep for her emotional pain, but never for physical.

Yeah.

I don't know.

That's absolutely, absolutely right, I think.

Yeah, yeah.

Yeah, and, and, and you were talking about the the deep sadness.

We were We did an episode about the the private voice of regret that.

Perry.

Or Adam Perry talks about the two voices of Virgil.

So and he talks about this whole idea that the Innit, of course, seems like propaganda on the surface, but there's something a lot deeper going on underneath.

A lot.

Everything's undercut.

And we wondered, has your opinion about the function of the Innit, what Virgil was doing?

Has that changed over the years?

Are you an optimist or a pessimist?

Yeah, well, I think the answer is that it hasn't.

My view hasn't really changed over the years, but my view has been since I was quite a young scholar, that one shouldn't be either an optimist or a pessimist.

I'll, I'll, I'll sort of explain that a little bit further because it, I mean, insofar as anybody cares, it's the kind of core of my, my reading of the, the really it's, I mean, on the one hand, there's absolutely no question that we, we're encouraged to note the some intensely negative implications of, of what Ineus specifically is, is doing so to, to worry about the consequences of the project that he's pursuing.

On the other hand, it's it's clear that there is a target in mind that the Roman readers of this poem would would, I mean by definition, would find positive the foundation of the place they they live in.

So what I've always suggested is that what we're dealing with here is an exercise by Virgil in encouraging us to understand that the most disastrous circumstances paradoxically generate the most beneficial outcomes.

It is a a weird and paradoxical idea, but he's writing against the backdrop of the Roman civil wars, which had been the most catastrophic experience of the Romans, and that the passage from civil conflict into what was hoped to be the peace, the Augustan peace.

So actually, the idea that that awful trauma that we experienced was a necessary precursor of a new dawn makes a kind of contemporary sense as as well.

Nobody believed me, by the way, and nobody accepts this reading of the but I'm neither an optimist, an optimist nor a pessimist in general in life.

Actually, I'm neither an optimist or a pessimist.

I mean in a way that's almost a Christian idea that all things work together.

And that's why I mean there is so much of Aneus that that seems to anticipate a Christian worldview that no wonder many people considered him a proto Christian.

But that's my off.

No.

Well, and these these these this text is being is coming out of a not dissimilar cultural circumstance.

And do you feel that Aeneas is therefore closely modelled on Virgil himself with his own experiences of of civil war and and Rome's context?

Or indeed is he?

Is he based on the Homeric version or other versions?

What is that amalgam of Aeneas's character?

Well, first thing I always insist with my students on on saying is that Ineas is firmly based on Ineas kind of thing.

He Ineas has to convince us that he's a he's an independent character who makes sense on his own terms.

Otherwise, you know, we don't, we don't, we don't care enough.

At the same time, yeah, there's there's there's lots of things that are kind of feeding into virtual's representation of Ines.

I think the most important are probably the Homeric hero, not necessarily in this order, by the way, Homeric heroes, including Ines in himself.

He's a obviously he's a character from the Iliad as well as other sources, and Odysseus and Achilles are important models for him.

But aside from that, most importantly, he's every Roman and with a strong element of Augustus, because Augustus is kind of presenting himself as every Roman as well.

Not every Roman in the sense of the, the man on the Clapham omnibus, not that kind of democratic idea, but the the ideal Roman or is aspiring to be the ideal Roman the ideal that Romans aim for?

I think that's that's the most important shaping, shaping influence on him.

So I'm that, that's, that's lovely.

I'm, I'm very into story structure and Hollywood screen writing stuff.

And they often talk about the character arc.

Does the character develop?

They often start off with a flaw.

And the whole point of the hero's journey is that they learn how to be who they're meant to be.

And I and I think in Stedman's commentary, he says he quotes somebody as saying that Eneas completes his arc by the end of book 2 now.

So what's the rest of?

Do you think Eneas has an arc?

Character arc he he does it's a it's a it's a character arc that doesn't resolve the challenges that he presents to the reader.

But I'd say that one important aspect of development of Eneas is is the knowledge that he heat gains.

This is this is probably a feature most of all of the first half of the poem, but it's it's it's relevant also in place like book 8 and shield and so on.

He starts off as somebody who who isn't terribly clear what he's supposed to do.

And, and in particular, when his major source of guidance, his father dies, he's go he goes completely off off piste and and and you know, spends time in Carthage.

You know, this is this is a crazy place for a Roman, the founder of Rome, to spend time by a slow process.

And an important moment is book 6 where he's hearing from his father again.

He meets his father again.

His father says that his is the future.

He learns, he gains the knowledge, he internalises the importance of what he is setting out to do.

And one thing that we're not concerned about in the second-half of the poem is that Ineus doesn't know what he's there.

Whereas in the first half of the poem, we, we are a little bit, I mean, if you're a Roman reader and, and your hero is hanging out in Carthage, something is pretty catastrophically wrong.

You know, hello, what do, what do you do?

You don't have that concern anymore.

You do have concerns, you know, that he's a, he can be a bit of a head case at various points in book book 10 in particular, you, you might well have concerns the Romans could tolerate extreme violence better than we can.

But even even they, I think would have been somewhat concerned about how he behaves the later point.

So yeah, in in some ways, certainly.

So does he actually, I mean, does he change at the end?

Is he different at the end than he was at the beginning?

And if so, in what way?

I mean, we did a whole episode almost on that, the violent ending and all the questions that raises which.

It's an interesting one.

I mean, the way I read the ending, I mean, it's related to what I was saying about optimism, pessimism earlier.

But more specifically, what's happening at the end is that when he sees the the Baldrick that that tennis has taken from Palace, he reverts to the state of mind he had after the killing of Palace in Book 10.

And there's a passage, you know, after the killing of Palace, when Aeneas is as terrifying as its possible to be, where he's committing human sacrifice, where he's giving no quarter, all these kinds of things, which is kind of resolved in Book 10 through Laosus and Mezentius.

And so, you know, everything calms down.

But for some reason, well, at the very end of the pack wants Sinius to revert to that really berserk kind of character that he had in in in book, in book 10.

Now, what we're saying there is that he's totally clear about what he has to do in a in a sense, he has to win the war.

Yeah, no doubt about that.

But how he wins the war and what he does at the end of them, I think Virgil deliberately makes extremely difficult to accept in a straightforwardly ethical way.

You think he was talking to Augustus?

I'm talking to you now.

Don't behave like this.

Well, I mean, yeah.

And the beautiful thing about this is that, you know, Augustus, you know, we have Augustus sort of writing letters to Virgil saying, come on, give us a bit, give us an idea what you're writing in the, in the innate.

And Virgil, you know, like any, any poet isn't, isn't telling him.

He he sort of knows.

I think he's writing something that is can count as sort of as propaganda.

Not, not, not propaganda in the in the sort of standard sense, but something that sort of serves the purposes of Augustus.

But he's doing it his own way and and it's what's made it last as long as it's lasted, I suppose his his own choice.

Oh, there's so much more.

Katrina, have you got a question?

Have still sticking with the nears.

He's going back to this idea that he was perhaps a traitor earlier in the sack of Troy, and whether that then influences how he's trying to redeem himself as he goes through then his later journey.

Do you buy that idea at all?

I certainly buy it in the in the sense that virtual in writing a poem about Ileus has a has chosen a hero who brings huge advantages to him that he's a Homeric hero, but he's also of the ancestor of Augustus.

But Ines also comes with quite a lot of baggage and quite a lot of unfortunate baggage.

So you can certainly see how Virgil's representation of Ines is implicitly designed to answer some of the alternative sort of correct, some of the alternative claims about what Ines did.

I mean, if you think about what he, what Ines does in Troy in too is he criticises himself.

He's describing this to Dido, of course.

He criticises it himself for acting irrationally in defence of Troy.

You know, he's had the dream, but he's forgotten the dream.

So he goes out and sort of kills as many Achilles as he can when he should be skedaddling because because Hector told him to.

So in a way, Virgil is kind of insisting on a particular fault, which is the opposite fault of being a a traitor.

You know, he's he's pushing the devotion of of Ieneas to such an extent because we've got to be convinced that Ieneas did absolutely everything he could to prevent Troy from falling.

There are there are other other things like, I mean, the whole story of Euless, his son, this son, he's got two names.

I mean more sound about, but there's there's lots of complication in the in the back history and alternative stories of.

Which say that, you know, Ineos didn't have any male sons or Ulus didn't have any male sons.

Authorities for people like NES and and Cato, you know, claimed this any of those you believe any of those.

And the whole structure of Virgil's idea falls down.

There's no ancestry between Ineos and and Augustus.

But the right, the important point that is this, that that Virgil tells the story so well, right.

Virgil produces a version of the Aeneas myth that is so powerful that it just wipes away any alternative account.

This becomes the authoritative account.

And it becomes the authoritative account because Virgil has just told it better than anybody else could do.

Yeah.

I was just reading actually 1 alternative account that Aeneas had several sons and that Espanius was the eldest and went off and was really Kingdom for a while.

And but that image of Aeneas with his dad on his back, who's holding the Palladium or whatever it is, and his son, the gender, the three generations, the father, the son, the grandson, is so powerful, isn't it?

Yes, incredible.

And as you say is they're in various places, but they're the previous generation on a coin of Julius Caesar.

If you want to convey your claim to power your claim to authority in, this is the is the way to do it.

So a slightly different question because as part of the podcast, we originally we start each episode with a different word and we often dive into a particular passage or a favourite simile of ours that we then go on to unpack a little bit and discuss and hear the Latin.

Do you have a favourite simile from the whole of the Anir Berlin and would you like to that either share it with us or give us a sense of why you feel Vigil's words are so powerful in some contexts?

Yes, though you'll I mean, I hope you're disappointed in in in what I say because that that's that's kind of the point.

My very favourite simile in the in the the brilliance of which came home to me in a tutorial many, many years ago with Chris Tudor, who's actually the person that runs Massillit.

But he basically said to me, we were reading book 6 and at the point when Ineus starts heading into the underworld, Ebent Obscuri and and so on they went in darkness, there's a simile.

And then I'm not doing Virgil justice here, but basically it goes like this.

Ineus and the Sybil are heading in darkness into the underworld and it was like a man walking in darkness.

So it's a simile that doesn't do the basic work of a simile.

I mean, the whole point of a simile is you've got to be kind of somewhat like what you're talking about, but then sort of different in other respects that really make you think about it.

And Chris said to me, you know, how, how can you justify your claim this this guy's a great poet when he's just he said, you know, the equivalent of words were saying I, I wandered lonely like a bloke wandering lonely.

And I said to him and having said to him, I actually believed myself.

You don't have to believe me.

The virtual such a great poet that he will risk that kind of criticism and what he's trying to do at this point is just bleed his poetry of all colour.

We're going into the the underworld, this place where stuff isn't quite there fully and colours don't quite work.

One of the effects he gets in the underworld is it NIA somehow has gone down to the underworld in sort of armour and he's gleaming, but everything else is kind of wispy and and hard to define.

And at this point he even sort of loses the colour that comes with similes that that light that sibiles bring into poetry.

The poetry loses it's it's in a sense as as as as we're running into the underworld.

It's an incredible.

But it's also good because of course everyone knows what darkness is like, and in the ancient world, darkness would be dark with no electrical lighting, and on a moonless night it would be terrifying.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Powerful in its simplicity.

I thought you were going to do the simile at the very beginning.

I think it's the first simile where the storm was like an orator.

Instead of the orator being like a storm, the storm was.

Or when Poseidon, when Neptune calms it like an orator calming a rowdy audience, which is a kind of reverse simile, is.

No, which is, which is, which is, which is fantastic.

I mean, he's, he's so clever with, with what he does with, with these.

I mean, in, in many ways, the similes of Aneas of the Aneas are doing a lot more than the similes of Homer.

Really, though, I think we'd probably assumed that Virgil thought the similes of Homer were doing more than we think the the maybe, maybe, maybe do.

There we get into the head of Virgil, which is an interesting place of which if.

So Speaking of the head of Virgil, just super quick and you might tell your students, don't try to do this at home, but what can we learn about what do we think about Virgil's life, like this whole attitude to mothers and his whole attitude to fathers?

Can we glean anything about Virgil himself from Leonia?

Do you think anything leaked through of his?

His trauma, his background?

I don't know, I, I, I sort of resist that.

I mean, the poetry that he wrote is so, so I mean, it's not as diverse as some as, as Horace or something, something like that.

But I mean from the clogs, from his pastoral poetry that is early poetry to the innate, it's difficult.

I find it difficult to see too much of the historical virtual there.

And I, I, I do see him as a, an, an astonishing artist that can create poetry that will do what he wants it to do without necessarily the, the element of, of personal, the personal element.

That said, you can't do what Virgil is doing in this particular genre, in the epic genre without implicitly or explicitly claiming to be a very great poet, only a very great poetic power.

He's adequate to tell such a great story, to tell a story that's a continuation of home.

And going back to that moment in book 2 where Hector appears to ineus.

I mean, one of the things I've learned, and it wasn't something I saw is something that another scholar had seen was that at that moment when Hector is, as it were, handing over the baton in Dreams to Ineus, Virgil is alluding to Eneus, the great predecessor epic poet in Rome.

And a point in Eneus where Eneus is explaining how he's writing epic and he's basically saying I'm writing epic because I am homo reincarnated.

So at that point it's there's a lot going on, but at the same but one of the same time, the hero of the hero of the Iliad, Hector, is handing over control to the hero of the ineered Ineus.

But in the background, Homer is handing the battle to Enius, handing the battle to Enius.

So in a very subtle way, Virgil is saying I'm a fantastic poet.

And that's fair.

You know he will.

Between that.

OK, then we have the quick fire round.

Are you ready?

No, but go ahead.

Team Ineos or Team Dido?

You'll know the answer team both team both the the you know it's it's a tragedy he had to leave, but you know, you wouldn't have the Punic walls if Ineos hadn't washed up on on Carthage and and had a love of her.

So, you know, you could say that both, as you would feel as much sympathy for both of them and condemn each of them just as much.

But that's the world as virtual story.

OK, would you trust Ankaeces or Helenus more?

If I were Ankaeces son, which which I might be in this context, I trust Ankaeces more.

He's he's got he's.

Camilla or Lavinia?

Camilla, absolutely every time.

She's an outstanding hero.

Yeah, Juno or Venus.

As as got the best speeches, you know, I mean, you're you're you're there thinking this can't happen, but Blimey, I'm persuaded that this should happen.

Yes, let's have a war in between the future components of of Rome in Italy.

Absolutely, Juno.

I'm completely persuaded.

Juno.

Juno is is is is definitely the the one.

Golden bow or special shield?

Special shield please, with all the sort of the future of my descendants presented on it in in in the finest artistic.

If you're Virgil, would you take more from any S or Apollonius?

In the bits that matter more from any S, but in the bits that people are more inclined to read, like book 4, Apollonius, Apollonius is is provides the material that that turn the pages.

And Professor Morgan, Virgil or of it well.

That's a tricky one.

Really depends.

I was going to say it depends on the day.

It depends on the time of day, really the time of day.

I mean, it's you know of it's offered for fun, Virgil, Virgil when you know, for for serious.

I mean, I can't decide.

I can't decide between those, those there's like, you know, Horace and Lucretius and the rest of them to compete.

There's not much humour in Virgil.

We were trying we we do a podcast on the humour in Virgil.

It would be very.

Short.

Very short.

Very short in indeed.

No, if, if, if we're looking for humour, definitely of it.

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Katrina, can I do the cultural questions now?

Please do.

Leads on quite nicely.

So we love pop culture and we wondered if you were cast on a desert island for your Desert Island Discs, what would be your three?

Well just three favourite songs?

Also your favourite movie that to take because I love movies.

This is the.

Clincher which book from the ancient world and would you take?

As well as, of course, the Bible and Shakespeare.

So your three songs first.

OK, fabulous, right, I'm going to go with Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis by Vaughan Williams and that that encapsulates a huge amount of my life.

And since I've mentioned Thomas Tallis, there's a there's a wonderful Latin setting for Pentecost called Lochway Bantour varies linguists.

They sang in in various tongues by Thomas Telus.

And at that point it was it was tough.

I was thinking between mainly Jonama trading and Leonard Cohen, but I'll go with Leonard Cohen.

There's a, quite a recent song by Leonard Cohen called, uh, Boogie St, which is just so profound.

That's not true.

Favourite film.

Very, very tough indeed.

But I'm going with a matter of life and death, the Powell and Pressburger movie, and I'll correct what I said before.

I, I, I think that, you know, given that it is a desert island, given that I'll, I'll need a, a, an improvement to my mood on a fairly regular basis.

It's going to be Ovid's Metamorphosis taking with me, yeah.

It's a win for Ovid in the end.

That's great.

Excellent choices in our, in our, I think we're drawing to an end.

You'll be cloudy.

No, no, I could go forever.

Ever look at you?

Anyway, in our third podcast based around the word Musa, we each wrote three Lyme epitaphs in the style of Virgil, supposedly self written epitaph.

So what would yours be?

OK, so I come from a place called Saint Helens in Merseyside, so that explains the first bit of it, which otherwise might be a bit worrying.

And I say Saint Helen bore me.

Oxford made me grow up, and I pondered Virgil, Horace, and a bunch of other random stuff.

So Arvidis even mentioned him.

There he could be the other random stuff he's.

Another random he'd take to the desert island.

Thank you so much for sharing.

That's quite personal and we really appreciate it.

And I think we're going to give you the Joan armour training.

Which one would it be?

Down to 0.

OK, brilliant.

Fantastic.

I'm going to go listen to all of those now.

Yes, we'll curate a playlist for everyone to listen to as they read their Virgil and have music blend.

Thank you so much for the well and that's been such a pleasure.

My pleasure.

We just want to say we're massive fan girls.

That's it guys.

That brings this series of the classics podcasters.

Virgils are near to a close.

Thank you for being with us.

There will still be some bonus material I think out there coming soon for you.

But we hope that you have enjoyed it, that you've taken so much away, that you have new thoughts, new opinions.

We'd love to hear them and that you will go away and keep rereading.

I think the key lesson that we have taken from this is that Virgil keeps giving us great things.

There's always new passages to explore, to rethink, to perceive in a different way.

And as Llewellyn says, that you can have the same thoughts that you had many years ago.

You can change them, but you can always revisit and be inspired by them all the time.

And if you get bored of Virgil, you can go to Ovid.

So maybe there'll be some offered content coming soon.

Thank you.