Episode Transcript

Cal: we will get started with the FAST five.

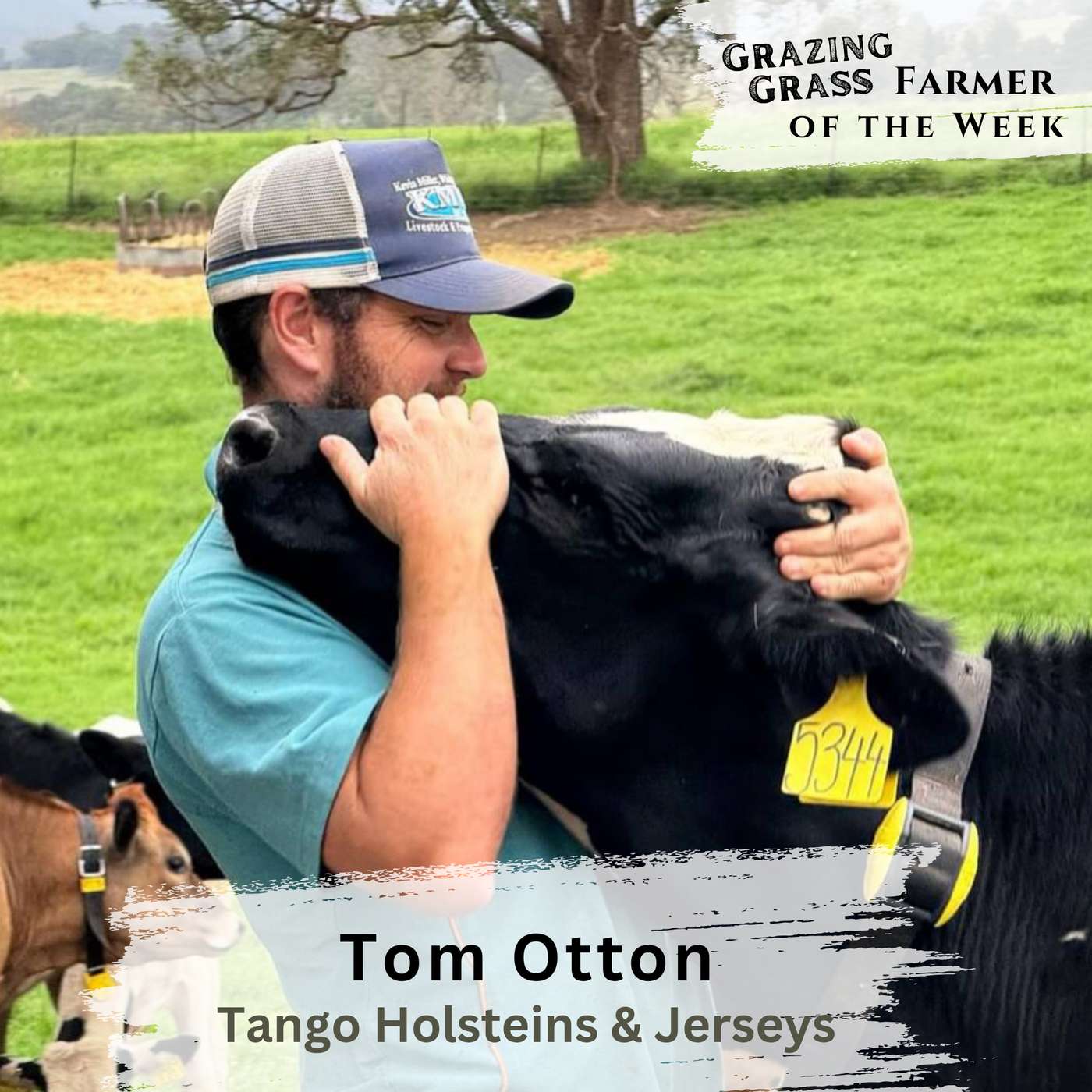

Our first question, what's your name?

Tom: Tom Otton Cal: And Tom, what's your farm's name?

Tom: uh, Well, we go by Tango Holsteins.

The farm doesn't actually have a name, but our sort of business name.

Our, our stud name is Tango Holsteins.

Cal: Oh, very good.

And where are you located?

Tom: We are in Candelo on the far south coast of New South Wales, Australia.

Cal: Oh, very good.

I'm glad you added all that else in there.

Or we were gonna have to say, our geographically challenged Northerner Northerners needed some help on that, but what species do you graze?

Tom: Uh, We grow a uh, sort of our more native grass.

That's probably more common to, to the east coast of Australia's kaiu.

Um, That's a summer in autumn pasture.

And Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: it can be very, very good for us.

A lot of farmers hate it.

A lot of farmers call it a weed, but um, I love it.

It's just grows Then through winter we do a lot of pasture cropping with all different types of cereals uh, rye grass.

And I mean, I'm a, I'm a big user of multispecies mixes, so I could rattle off 20 or 30 different plants I've planted over the years.

Um, But yeah, kaku, you rye grass and then some sort of cereal with clover is predominantly what we graze.

Cal: and just FYI for our Northerners listening, it's the middle of winter for you while we're, it's stuck in summer.

Tom: Yeah.

Yeah.

It is very cold.

It was minus one, ugh, minus one Celsius.

Another thing I'm gonna have to try and convert, I should have uh, should have done some Googling beforehand, but um, it was below freezing this morning, which is not, I mean, it's cold for us, but it's not cold for you, you guys up north there that really Cal: yeah.

Yeah.

And what year did you start grazing animals?

Tom: Uh, I've been a farmer my whole life, so I grew up on um, 1500 acre beef farm.

And uh, when I left school, I, we went dairy farming.

We left that farm, we left the family farm and went dairy farming.

So I've been grazing animals basically my whole life.

Cal: Welcome to the grazing grass podcast.

The podcast dedicated to sharing the stories of grass-based livestock producers, exploring regenerative practices that improve the land animals and our lives.

I'm your host, Cal Hardage and each week we'll dive into the journeys, challenges, and successes of producers like you, learning from their experiences, and inspiring each other to grow, and graze better.

Whether you're a seasoned grazier or just getting started.

This is the place for you.

Ranchers, farmers and landowners, if you're looking to optimize your grazing operation and boost your bottom line, Noble Research Institute can help the noble approach to education pairs their own infield research with the expertise of ranch managers and advisors to find practical solutions to your unique challenges.

In July, Noble's in-person courses will head into new areas.

Join them in McKenzie, North Dakota, July 15th through the 16th for Noble Land Essentials.

And in Pendleton, Oregon, July 30th through 31st for Noble Profitability Essentials.

The expansion doesn't stop there.

Later this year, they'll be in Winter Garden, Florida with the Business of Grazing.

And right now, each of these two day courses is $50 off the regular price.

The pricing is available for a limited time, so take advantage of the savings and visit noble.org to learn more about the courses and enroll today.

For 10 seconds about the farm, July is here.

I would say finally here, but man, it's happened quickly.

In the first six months of the year, we've had a tremendous amount of rain.

I wanna say the second highest, maybe the third highest.

I know 1973 was on the list.

2019 was on the list in 2025.

I wanna say it was second.

A lot of rain.

Like 32 inches worth.

And normally we get about 44, so you can see where we are this early in the year.

Because of that, we've kind of changed our plans up a little bit.

We had no intentions of belling any hay.

However, with the ample rain we've had this year, uh, we've got plenty of grass and.

We're thinking we're gonna go ahead and use the opportunity to bell some hay, put it in the barn so we have it.

Um, and next year we'll get back to not bailing any hay for 10 seconds about the podcast.

I think I told you last week.

Don't use grazing grass resources.com.

It's not working.

Well, I tested it last Wednesday and it's working.

I thought I had the settings right, but it wasn't showing up right.

But I did talk to a lady in Texas and she went to the Grazing Grass Resources to look for a mentor near her.

And I know the Grazing Grass resources are young, but if you're interested in being a mentor, if you're a consultant, you should be listed there.

She went there looking and we do not have anyone from her area in Texas listed.

So I told her I'd put it out there.

Let you all go to grazing grass resources.com and put your listing there or list your farm that way if someone's looking for a regenerative farm in their area, they can find it.

I have my farm listed there and.

Maybe we can help each other build a, a tool that's beneficial to the community.

With that said, once you finish listening, go make your account and get your listing there.

And let's talk to Tom.

I.

Cal: Growing up on a beef farm.

What made you switch to dairy cows?

Tom: Well, I'm not sure whether the northern hemisphere knows this, but Australia went through a horrible drought from 2000 to 2010.

Um, The millennial drought, I guess they'd Um, There was horrible water.

Lot of farms closed down because of it, and.

I finished school in 2010 and the farm was, it was in the recovery stage of that drought, but it was still doing it very, very tough.

And I, my then girlfriend, now wife and I were working on the family farm and realized that there was no opportunity there for Um, We were living there and sort of working on it, but not really getting paid.

And um, I wanted, I wanted to stay there and, and do lots of things there, but it was pretty obvious that there was no money for us to stay there.

Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: um, I put a few feelers out and a local dairy farmer uh, lives now lives very close to us at the time, was maybe an hour away from us.

Um, He said, come and work for me and.

Get to know the dairy industry a little bit.

And I thought this was a fantastic opportunity.

The job come over the house and uh, at the time it was pretty well paid.

And so we, we jumped into dairy farming and that was in 2012?

2011.

2012.

And we've been milking cows ever since.

Cal: Does she have a history in grazing animals?

Tom: She, her parents have a hobby farm.

Uh, We had horses when I was growing up, we had show jumping horses and in a pretty big, in a pretty big way when I was younger and we both met through with horses and yeah, we got.

Well, yeah, to skip over a few years, 2015 we got married and we decided to leave the farm we were working for and, and start leasing or share farming share farm.

I'm not sure if you know what share farming is, but we started share farming in 20 uh, very early 2016, January, 2016.

Yep.

Cal: Oh, very good.

With, with that first dairy, were they practicing what we would consider reti practices?

Tom: Yeah.

So this is, this is what I've been thinking about for a long time now, that, so the word regenerative, I'll go into a bit of a deep dive here.

The word regenerative has only really come about for me in the last four or five years, and I actually employed a bloke that said regenerative.

And it was the first time that I've heard that word.

And when I started looking into it, I thought, we've been doing regenerative practices forever without knowing that we're doing regenerative practices.

We do it because I.

We think it's more profitable.

Well, it is, you know, we know it is more profitable.

I dunno whether that's just a uh, a Southern Hemisphere Australia and New Zealand thing.

But you look at all the farmers in New Zealand, all the dairy farmers in New Zealand, and, and they're doing multiple shifts a day and they're using all sorts of organic composts and they're doing all sorts of cool regenerative practices, but they don't know that they're regenerative farmers.

Um, So yeah, it's, it's interesting when I started going down this rabbit hole of regenerative farming and, and found people like you and, and John Kemp and Gabe Brown and um, those sorts of guys, and then I went, you know, we've, we've been doing this forever, but we didn't really know that we were doing it.

Yeah, it's interesting.

Cal: You, you know, I can remember my first exposure to the word regenerative and that's because Greg Judy started his YouTube channel and he put on the regenerative g grazier Greg, Judy.

And I'm like, what's regenerative grazing?

And you know, I'm like, oh, that's what I've been trying to do or attempting to do for decades.

Tom: just because it's more profitable and it grows more grass.

We didn't know that we were doing this cool, trendy, regenerative practices.

We just knew that it was more profitable.

Cal: Right?

I was trying to lower cost, make more money.

Tom: that's right.

Yeah.

Cal: Yeah.

And, and I've always been fascinated by the New Zealand dairy industry because I grew up on a dairy.

And for us, we were, I hate to use the word grazing.

Our cows were own pasture.

But we had two pastures a day, pastor and pasture And if you don't understand what those were during the day, they went to the day pasture And during the night, they went to the night pasture And that's, that's the way my, my grandparents did their cattle, you know, and we fed a concentrate as they came through the dairy barn.

And we just, when I went to college, I worked on a dairy and they were completely confined.

So, you know, I hate to use the word grazing, but they were on pasture a little bit, but not ative at all.

Tom: so we're um, so we're doing minimum two shifts a day.

When we have time, we do four shifts a day.

Um, But we're, we're sort of sitting at around 150,000 pounds per acre to put it into American And yeah, it's not highly dense.

That's on uh, two shifts a day.

But when we go more density, when when we've got the grass to go more dense, then we'll push it up to sort of three, 400,000 pounds per acre.

Cal: Oh yeah.

At what point did you start looking at your density per acre?

Tom: Uh, We sort of always um, I'm not sure I ever started doing it.

Um, Yeah, I've been doing it forever.

Really?

Cal: and with your, your two shifts up to four shifts, are you?

Are you going out there running a new break for him or do you have any automation to go with it?

Tom: No, no.

We're doing, we're doing it very manually with uh, polywire and, and It sucks.

But yeah, it's the same thing.

We've been doing and we know that it grows more grass by doing it this way.

The virtual fencing thing, we could go down that rabbit hole.

It's incredible.

I love, I love the idea of it.

It's only just become legal where we live in the last two months and I dunno, of anyone around us that's even thinking about putting it in.

But I think that it's the future.

I think for, especially for my operation, it's exactly what I need.

Cal: Now, you mentioned something there, you said just became legal there.

Why was it illegal?

Tom: So is it fully legal in America?

I, I assume there would be lots of states that would, where it's still, there's still some states in Australia where it's illegal.

South Australia and Victoria, I think.

Cal: I didn't even think about there being any regulations to keep you from doing it.

Tom: Yeah.

Yeah.

Cal: my mind, and, and I haven't dove into it.

I mean, I've talked to people on the podcast that's doing it, but it never crossed my mind that it might be illegal Tom: Yeah, well, the animal activists love to keep that sort of thing illegal.

But yeah, I think it was in, maybe May, may this year it become legal.

I actually did a interview with a local radio station about it about the benefits for local dairy farmers using virtual fencing.

Cal: Oh, okay.

So it's, it's illegal due to animal welfare concerns.

Tom: And that was the, during the interview that the interviewer asked me, are you worried?

You know, many times he was pushing me almost to say, yes, I'm worried about the animal welfare issues.

But no, it's not.

It's not.

If you know any people with virtual fencing, there's, there's no animal welfare issues with it.

Cal: Is that because of the potential shock the cow gets,?

Tom: It's because of the shock.

Yeah.

We've got collars on cows at the moment.

We've got the data.

Mars collars, heat detection and, and rumen rumination activity collars.

We've got them on.

We've had them on for one eight months.

Cal: Oh, yes.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I don't know.

So for the states, you know, the state most likely to have some kind of regulation on that would be California.

Of course there's some other states, but California seems to be the first for animal welfare.

And I don't know anything like that here.

I wonder how it is in Europe because they're, they're pretty concerned about a animal welfare there as well.

Tom: I'm not sure it Cal: Not, not that we aren't, but you know.

Tom: yeah.

The, it's just an overreaction, you know, the, the shock that they get is so small, you know?

That's just silly, even to think that it's an animal welfare issue.

Cal: Oh, yeah.

Yeah.

So does that have the potential, and this is more a question for listeners, is electric fence legal everywhere or is that a problem for some Tom: Well, that's what I've often wondered that too, because, you know, you're, you're always trying to get your fence to run at 10,000 volts and, Cal: Right.

Tom: and we're putting a collar on a cow and I, I think it's half a volt or 0.3 of a vol or something.

So Yeah.

Why haven't energizers been made illegal if colors have been made illegal?

Yeah, I dunno.

Cal: Years and years ago, actually, if you go to my, my old YouTube channel, I say my old one for the farm, I haven't updated it in years, but I got a shock collar for one of my livestock guardian ducks.

She just didn't wanna stay in with the sheep.

And it was one, I had to run a wire around the pasture where I had 'em.

So I had 'em in a small pasture and I was trying, and I thought, you know, for good YouTube tv I might as well get shocked by this thing.

And of course, so I did that and I, I dropped it because I didn't like getting shocked.

But I would rather get shocked by that than my electric fence when it's running pretty.

'cause it makes my funny bone hurt.

And when my funny bone hurts, I know my electric fence is in good shape.

Nothing's gonna bother it.

So with your cows and talking about let's just talk about your cows.

What breed are you milking?

Have you always been that breed?

Tom: So we milk Holsteins.

We have got a few jerseys maybe a dozen.

So we milk around 220 Holsteins, and then we've got about 10 or 12 jerseys.

My wife loves jerseys.

My kids love jerseys.

I, Cal: Everyone loves Tom: yeah, I think they're cute.

They are, they are.

I mean, I, I admit it.

They're cute.

But now when we started off, we bought a very mixed herd.

So in 20, when we bought our first herd in 2016 we pretty much just bought the cheapest cows we could find.

And then I knew that by value adding to the herd, I had to breed the herd to a more Holstein herd.

Yeah, I'm not sure if it's the same everywhere, but here our whole state cows, just commercial grade, whole state cows worth double the price of a, of a decent jersey.

Even though they might be exactly the same, profitable, just the, the resale value on a Holstein cow compared to a Jersey cow is double.

So, so I knew that the banks, you know, I'd look better to a bank if I had 200 Holsteins compared to 200 jerseys.

It was just pretty common sense to go that way.

Not that I really, I don't really like one breed over another.

That was just the way we went.

Cal: Are you AI in all your cows?

Tom: So we used mostly US genetics, north American genetics.

We, we put an emphasis on type and we don't want sort of, we don't want the big show cows.

They've still gotta fit into our grazing system and they do a lot of walking.

So they've gotta be medium stature and they've gotta have good legs and good ERs and wide chest wide muzzles.

I.

Yeah, we put a lot, a lot of emphasis on confirmation in our Holstein cow and, and make sure we get it right.

We don't want, we don't want a bad line of heifers that all come in.

They're all narrow chested and they're all too tall and they break down.

They don't go in calf.

Yeah.

So we put a lot of effort into that.

Cal: Yeah.

Oh, continuing on that, are you using sex semen or are you just using conventional semen?

Tom: Yeah.

So one of the things one of the sustainable things that we tried to do when we first started farming was to go down the sex semen route.

I would say we're one of the very early adopters of sex semen in Australia.

So we use sex se on our best cows and, and beef on our.

Worst cows, I guess they bottom half cows.

We haven't actually used a conventional Holstein bull or a conventional dairy bull since 2017, and I would say we are one of the, the longest, if not the longest, in Australia for, for never, for not using any conventional semen.

Cal: Oh yes.

What beef breeds are you crossing on your dairy cows?

Tom: we try to use Angus a lot just 'cause of the resale value.

But the Angus straws, I'm not sure if they are where you are, but Angus Siemens straws have gone through the roof the last couple of years.

So we actually found some cheap now I wanna get this wrong limb, flex limb.

Limb flex Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: which is a Angus liers in, I think.

Cal: Yes.

Tom: So we, we are using that at the moment.

We'll see.

See how that goes.

I.

Cal: Years ago when we dared neighbor had limousine and then we, we had a few beef cows and stuff, but the great thing was he would give me old limousine semen he didn't wanna use anymore 'cause they were just trying to keep up with the times.

It worked out really well I wanna talk about your infrastructure a little bit, but before we go back and talk about that, you're breeding some of your cows to beef calves, I assume you're bottle feeding them and selling them at how big?

Tom: Sort of six to 12 months.

It depends a bit depends on the market a bit.

But we get 'em to past we stage and, and until they're, there's a lot of inner areas, a lot of I wouldn't call 'em hobby farmers.

They're better than hobby farmers, but they're people that as soon as it gets dry, they don't really care for their animals that much.

So they, or, or they don't understand.

It's not that they don't care.

They, they don't understand that cattle need to be fed.

So we try and get 'em big enough for that market, for those people that have got maybe 50 acres or a hundred acres.

So they're bigger than a hobby farmer, but they're not a, a full-time farmer that would understand.

And so we try and get 'em big enough so that if it does get dry, because where we are, we're we are the epitome of feast and famine in our area.

We have very low rainfall, but we can get 80% of our rainfall in a week.

And so people will be buying, buying, buying.

They've got lots of grass, but then inevitably we'll get a severe drought within a couple of months of that big flood.

Cal: Yeah.

I, I like to say in May everyone hears a great grass manager.

Tom: that's, that's Cal: when it dries off, we, we really see how good people are.

So how much rain do you all get each year?

Tom: So where we are, we're, we're in the Bega Valley.

If you look up on a map, the Bega Valley is a beautiful part of Australia.

I think, I think it's I'm definitely not biased at, at all.

I think it's the most beautiful part in the world.

We're on the western edge of the Bega Valley, and so we have about a 550 mill rainfall, which helped me out 20, 20 inches.

20 10, yeah, 20 inches.

I think rainfall.

Cal: Or Boy, I was gonna let Google help me and I typed the wrong deal and it thought I meant miles.

Why is it Tom: I think it's, I think it's, well it's 25 mils an inch.

10 10 inches.

250, 20 inches is 500.

So let's say 22 inch rainfall.

Cal: Yeah.

About about 20 inches of rain.

Yeah.

Tom: And we get very hard.

Winter's cold, not snow.

We don't, we don't get snow.

We get snow maybe an hour from us or less than an hour from us Cal: okay.

Tom: But we get very hard frosts like the ground and everything will just be frozen for three or four hours in the morning.

And we'll get that nearly every day through winter.

And so, so yeah, Cal: Do you get, do you have periods of time where you guys are below freezing for a week or Tom: nah, no, our, our midday temperatures even, even, it might get to minus five, which again, I'm talking Celsius, I dunno what that is in Fahrenheit, minus five Celsius.

Our midday temperatures will get Cal: What is that?

10, 15 degrees, something Tom: yeah.

So our midday temperatures will get to sort of 15 to 20 degrees, which is, you know, a nice, Cal: Oh, okay.

So pretty mild.

Tom: Yeah.

Cal: Yeah.

And you mentioned your rainfall has the potential to come in a very condensed time of the year.

When do you typically get rain?

Tom: whenever, where it's autumn, autumn is probably the most reliable time of year, which is our February, march, well I'll say February, February, March, April is our, typically our autumn or your fall, which is I guess your springtime.

But that, that's most common time to be getting rain then.

But we could get 400 mils in July and then get 150 mils for the rest of the.

11 months.

That's, it's very common.

We get, it's called an East Coast low, and it's just a low forming off the east coast of Australia around Sydney.

And we're, we're about five hours south of Sydney.

And it'll sort of follow the coast down of Australia and then just dump it on us.

And, and I'm not exaggerating.

We'll, we'll get 400 meals in two days and then, and then we'll get four meals for the next five months.

It's quite extreme.

Cal: yeah, with those extremes, that, that requires some creative management, I would think.

With grazing your animals, Tom: Yeah.

Cal: are you, when you get a lot of that rain, are you worried about pugging in your pastures or do you do anything different with your cows during that time?

Tom: no, not really.

We don't have the sort of soils that pug, well, when we, we do, but what, what I've been trying to do for well forever is trying to build soils and build pasture mixers to hold that water in the soil for longer.

I, I've got a funny saying, it's called bipolar farming, that we, we say a lot around here, bipolar farming.

It's the highs and lows of farming where you know, we can be going really, really, really good this week, and then next week it's terrible.

And then the week after it's really good, the next week it's terrible.

So I've been trying to farm with a simple approach, whereas the, the extremes, the highs and lows, the bipolar farming isn't so extreme.

We're, we're trying to build soils to hold moisture in soil for longer and trying to grow different pasture mixes that will l last longer through those more extreme dry periods that we get.

Cal: so with your pasture mixes, are you broadcasting those in or No.

Tilling them Tom: No till.

We've got a, a Duncan Triple disc which again, very different to Northern Hemisphere farmers.

I would say 80 to 90% of farmers in the southern areas of Australia are using no till or minable till no-till.

So it's just a disc, a disc seater, like I assume they're popular in, in America, like a, a double disc or a triple disc seater, just runs it straight sort of puts the seed two inches under the ground and then a press wheel goes over the top of it and closes the, the grass over the top of it.

So we'll do cover crops as well as.

Minimal till or, or zero till.

I guess it's zero till.

I don't really know the difference, but yeah, we, well have, I've never used a plow.

I don't own a plow.

I have no intentions of using a plow.

I think a plow is a good garden ornament.

And that's about it.

Cal: yeah.

Well, I'd love to do a look out my window.

The rain finally hit here.

I'd love to have a pasture drill, but I'm not that rich yet.

Those, those things are Tom: They are, yeah.

This one we bought probably 10 years ago for 20,000, and I think if I sold it now 10 years old or, well, it was probably 20 years old when I bought it, so now it's 30 years old.

I think it's worth about 50,000.

So Cal: Oh, Tom: it's crazy.

Cal: I, I had a neighbor live up the road from me.

He passed away, but before he had, he purchased a no-till or pasture drill that caught on fire, Tom: Yeah, Cal: and he was very mechanically inclined and really good welder and fabricator, and he went through that thing and fixed it all up at his estate sale.

I thought, oh, maybe we can get our hands on a pasture drill no-till drill, so we could go a few thousand for it.

It went for like 23 or 26,000, so it didn't come home with me.

Tom: Yeah, it sounds similar to here.

Cal: Yeah.

But, but he did a great job of refurbishing that.

I just need to look for a, a pasture drill that's caught on fire, except I don't have his talent to rebuild it.

Tom: I've often thought about broadcasting and I'm not brave enough to do it.

Plus we own the drill, so, but I, I'd love to, I'd love to broadcast and just nail the time in, you know, during a sort of a, a rainy period and just see what happens.

But I haven't been brave enough to try it yet.

Cal: Oh yeah.

I, we broadcast some because we don't have a, a no-till drill.

And I have to say in defense of the government, there is one at our county extension office.

We just have to rent it from 'em and get it out here.

And we've not done that, but we broadcast from time to time.

And I, and I have to say, sometimes I think I'm smart when I broadcast and sometimes I think I am one of the dumbest people around because it, I don't see any results from it.

Tom: I think the timing is crucial, even with a drill.

I think the timing of of getting seed in the ground is, is very important.

Cal: With your, your drill, what kind of grasses are you putting in?

You mix?

You mentioned some mixes Tom: Give me one second.

I'll, I'll bring up what I put in this year because Cal: Oh, okay.

Tom: So we.

Cal: And also what's your timing on that, Tom?

Are you, I think you mentioned cereal grains earlier.

So is that a cool season crop for you?

So you're putting it Tom: So it's all, Cal: in Tom: all cool season.

Okay, you ready?

So this, this is the mix we did on about say 220 acres of ground we sewed this year.

So we did a cereal, which is Sayer oats.

We put Concord two, which is a rye grass.

We'd put some prairie grass chicory.

We did a leafy turnip.

We did three types of, no, two types of clovers.

I'm not actually sure what that is.

And there's another thing that I'm not sure what that is.

And then a, a type of plantain.

So, Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: yeah.

And then we also broadcast also I did broadcast.

I broadcasted, loosen on top of that with a type of fertilizer.

Afterwards.

Yeah.

Cal: Oh yeah.

That worked pretty well for you.

I, Tom: The multi-species mixes Yeah.

Have worked really well for us.

Yep.

Cal: yeah.

Are you planning annuals there?

Is that better milk production than your grasses you already have in place?

Tom: Yeah.

Although, because we have such a, such a good ous, summer native grass base, we plant annuals through the winter, and then the, the native summer grasses go dormant through winter, and then by about November, December when the, the annuals, the winter annuals are dying off the summer perennials, I guess you'd call 'em, start growing again, just naturally.

Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: yeah, we, we just do that year after year, so about March every year we try and sew the whole farm to winter annuals.

Then by November the winter annuals are dying off and the, the summer annuals, or summer pastures are growing.

And we go into that.

Cal: Are you feeding any hay or hay leads or silage to your Tom: Yeah, we do it.

We are pretty conventional in the way we grow silage and, and hay.

What, what a silage.

What a bale.

Silage.

Silage.

We have done pits in the past when we've had a really good spring.

But yeah, most, mostly just bale silage and, and through winter, like at the moment, we'll feed silage out with the cows in the, in the paddock and just when we're a little bit short on grass.

But yeah, I, I would like to get to the point where I'm not so reliant on silage, but it's a bit like a few other things.

I'm just not quite brave enough to, to do that just yet.

Cal: You know, we're all on this journey and there's things we have to do along the journey we'd like to not do, but you're just not quite far enough along yet to go there.

Yeah, just keep working towards it.

Let's talk about your infrastructure a little bit for your dairy.

So what kind of barn do you have?

Tom: We don't have a barn.

We, we have a, we have a milking shed.

We call it a dairy which is where the Cal: Oh, okay.

Tom: But yeah, we, we never put cows inside.

The cows are outside 365 days a year.

24 hours a day.

We have a, a dairy, it's a little tenic side.

Dairy takes us about three hours to milk, 220 cows.

We milk them twice a day, 5:00 AM and 3:00 PM it's a, yeah, it's a very small, we call it a dairy, but I think you call it like a parlor or milking parlor or something like that.

Yeah.

Cal: Yeah.

Dairy Barn parlor.

Milk barn.

Yeah.

Tom: Yeah, so, Cal: So tend to the side.

Are you using swing, I assume rather than low line.

Tom: So we're double up.

So we have 10 cups on each side.

We can milk 20 cows at Cal: Oh, okay.

Yeah, we were.

W we just had a double four herring bone when we were milking.

I, I dreamed of a bigger barn, but we never got there.

Tom: Yeah.

Well, this started as a six and then it went to an eight, and now it's at a 10.

And I'm, yeah, I have, I'm very excited for the day we pull this one down and just build something else because it's, I, I spend more time in that parlor than I do at home, I think.

Cal: I, I know when we, when we got started and was daring with my uncle and grandparents they were milking a lot of cows through a old double four swing.

And it was, they were milking like five and six hours.

It was, it was a crazy ti period of time there trying to grow the herd and figure out what to do with your, with your double 10 are, do you have automatic takeoffs and are you pretty computerized in the Tom: I would say so.

I wouldn't, I mean there, there's some very flash, fancy parlors in Australia because, you know, people don't like to spend more than sort of an hour in there.

We've got too much to do.

So there is some very fancy ones.

Ours is, ours is a very, very old parlor with some lipstick on it.

That's about it.

Cal: Yeah.

Well, you, you gotta be careful.

Those parlors can get really nice and really expensive and you're, you're like, they can do what?

Tom: They're, yeah.

Very expensive.

It's incredible the price of a, just to build a new dairy.

Here we are looking at millions and which is why I've put up with our little dairy for so long.

Cal: Just on, on the subject of milking, have you ever thought about a robot milker?

Is that popular?

Tom: It, it's becoming more popular.

I'm not against the idea.

And if, if, and when we decide to build a new parlor, we'll be looking at robots.

Definitely.

I'm not sure it will happen.

I, I don't know.

Yeah.

It, it'll be an interesting case study anyway for if and when we go down that path.

Cal: Yeah.

I, I think they're very interesting and I've seen some, some discussion about them on grazing dairies, and I know there's a dairy not too far from me with a robot, like an hour away, and I really want to go visit it.

I haven't convinced my wife that I can just stop in and talk to 'em, but.

Tom: I'm sure they love it.

There's one near me, they milk 400 cows.

They've got six robots.

But they, they do have a feed pad, a concrete feed pad.

So the cows are yeah, they, they go on grass a bit, but, but not a lot.

If I was to do it, I'd try and have the cows on grass sort of 95% of the time.

So yeah, I'm not sure how that works.

I know there's a lot of farms in New Zealand and Tasmania that have, that have robots and do what I'm trying to do.

So yeah, I'd go and look at them whenever we go down that path.

Cal: Yeah.

And, and I think with virtual fencing, the ability to, to auto move those cows and it, it, it'll be interesting where all that Tom: You're talking my language now.

I'm, I'm excited about that.

Cal: yeah.

Not, probably not something I ever have to worry about, but man, I, I could just I.

They can bring the cows in, you can have your robots going and you're there providing tech support.

Tom: Yeah.

That's it.

Yeah.

Power's a power's a bit of an issue.

I'm not sure.

Our power in Australia has gone through the roof in the last five years pretty much since Cal: Oh, yes, Tom: and robots are very heavy on power.

So I'm not sure whether there's a more sustainable way with solar panels or something like that to, to ease the load of power.

But that's probably one issue with the robots.

Cal: Oh yeah, of course.

You wait another decade.

It'll be amazing what they can do.

And Tom: Yeah.

Cal: on both ends of that, generating the power as well as what the robot requires.

Of course, if you'd like me, I'm gonna buy a robot in 10 years.

That's 20 years old, so it's, it's already out there working with your.

Your infrastructure, get cows out to where you need to graze, and they're coming back to that barn twice a day.

How have you done your infrastructure, so that works well for you?

Tom: We've, we've got laneways, so we've got central laneways all over the farm sort of thing.

They're, they're not great.

They're, they're, they're actually very bad laneways.

But I'm trying to make them better without spending too much money, I guess.

Probably one interesting part of our farm is that we're divided by a very big road.

So our cows actually go across the road.

We go over the road.

Once a day or, or twice a day.

We go across the road.

We are looking at putting in un underpass at the moment, but damn, those things are expensive too, so, yeah.

So yeah, our, our road is our bit of an obstacle to our central Laneway, I guess.

I'd like to, yeah, I'd, I'd like to be a lot more efficient in the way our cows walk to and from paddocks.

But the road is a bit of an obstacle there.

Cal: Oh yeah.

For your, your lanes, do you have anything down on the surface of the lanes or are they just where you made the lanes and they've been your Tom: Yeah.

Yeah.

We, because of our, you know, we, we don't have those really long wet winters like a lot of Southern Australia does.

Our winters are actually pretty dry and cold, so our layaways are.

They hold up very well.

They might get a bit messy for maybe two weeks when we get a massive downpour of rain, but after two weeks they're, they're fine.

Again, Cal: Oh yeah.

Are your lanes are they just like high tensile wire, single wire, or are they more elaborate?

Tom: bit of a mixture, depends where they are.

If, if it's only where the herd will walk, then they're just single wire electric fences.

If they're sort of towards the back of the farm where there's dry cows and heifers and things, then we have maybe three barbs and one electric wire.

trying to, trying to keep bulls away from the herd is always an issue, so we have to have sort of half decent fences to stop the bulls getting in the herd.

Cal: Oh yeah.

What's your watering situation?

Tom: So we have a really beautiful river called the Tenter Welo River.

I won't spell it for you 'cause I don't even know how to spell it.

Cal: Yeah.

Tom: Then we, yeah, we pump to a water tank and then gravity feed to water troughs.

The cows drink outta the river a lot.

And we also have a, a couple of dams.

I don't know if you if dams are popular there, but everyone has dams around here, sort of we're, we're fairly hilly topography, so that's very easy to put in a dam and, and cows drink from it.

Cal: Oh, yes.

So, so basically a pond.

But what do, do you have a a different word for that?

Tom: A, a pond like a, a dams just like an excavated hole in the ground at the bottom of a hill.

Cal: Yeah.

Oh, okay.

So not as big as what we would consider a pond.

Tom: It might be one or two megs.

I don't know what Cal: Oh, yeah.

Yeah.

When, when do you normally keve your cows?

Are you a year round keever, or do you keve a couple times a year, or you're seasonal?

Tom: We, we carve once a year.

I wouldn't say seasonal because we don't really have seasons.

We're quite unique in that we can be cut in silage in the middle of winter, in the middle of summer.

Anytime.

Anytime it rains, pretty much we can be, we can have the best time of the, you know, the best grass of the year at any time of the year.

But from a management's perspective, we carve once a year, we carve in our, in our autumn or our fall, which is we start on the 1st of March through till, well, I, I say June, but I've actually still got cows carving at the moment just 'cause we got a bit slack.

But so 1st of March till about mid-June is when I ideally want to have all the cows in the dairy.

Cal: So, so they're freshening and then they're going to be grazing those annuals and other Forbes you planted.

So they're gonna be on that nice high plane of nutrition when they're earlier in their lactation.

Tom: Yeah, so I try and have the whole herd dry when I'm planting.

So February, march is when I'm planting.

Then I try and have the majority of the herd dry during that period.

And then by the time they're in peak milk production, they're on the new grass, they're on the new multi-species mixes.

And then through sort of April, may, June, we can really get a lot of meal care that cows.

Cal: Oh yeah.

How does that work from a selling your milk perspective?

I assume you, you have a bulk tank, come take it to a cooperative or a Tom: Yeah.

Cal: processing plant.

Tom: So Be Cheese.

I don't know.

I dunno if Be Cheese is popular, the, the name brand, but in Australia Be Cheese or, or Bega Foods I think they're called now is a huge I'd call them a multinational maybe, I dunno, a huge company in Australia.

Anyway all started from a little tiny cheese co-op in Bega, which is about half an hour from me.

In 1899, they started bega cheese and all the local dairy farmers set their milk.

There.

And then Bega cheese has just grown and grown and grown and grown.

I think they're worth a $4 billion company or something at the moment.

Cal: Oh yes.

Tom: so all our milk goes to Bega Cheese.

We only have one cooperative in our area, so we, well, it's not a co-op anymore, it's a publicly listed company, but we only have one processor in our area.

So all our milk goes to Bega cheese.

We produce around four or 5,000 liters a day.

Our milk tanker comes.

Picks up.

We have a bulk tanker, a vat we call it.

A milk tanker comes and picks it up every day and, and takes it back to the bigger cheese factory and turns it into cheese.

Cal: Is, you know, growing up on dairy, we milked every day of the year and we had cows ke year round so that we could be shipping milky year round.

I know in New Zealand it's that very seasonal.

All your cows are dry, they're all freshening.

What's the main way in Australia?

Do they follow more of that New Zealand type where most people have time off because cows are dry or are there some that's milking year round?

Tom: I would say the, the most popular way of carving cows would be two batches, a batch in the Otto and a batch in the spring.

Which is what we were about only a few years ago before we decided to go to one batch.

There is still a lot of farms that carve year round and they'll have cows carve in every single day of the year.

It's still fairly popular, but the New Zealand system, I would say is becoming less and less.

I, I would say 1% of Australian dairy farmers actually stop milking through winter, like the Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: New Zealand system.

Yeah, it's becoming a lot less and less, and that's just because our winters here in Australia, well, they're not nearly as hard as they are in New Zealand, so we can actually, Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: we can actually grow grass and we can actually keep cows on grass through winter.

Whereas in New Zealand, trying to milk cows in winter is just insane.

And I dunno how they do it.

It's just raining every single day of the year and yeah, it'll be impossible.

So.

Cal: Well, I, I know when we dar it, I always looked at that and thought.

How great would that be to turn your cows dry for a couple months before you kick back in gear?

Tom: Yeah, I, I'd like to get to that eventually with the way we are doing it.

But yeah, we, we, we'll probably never get there.

We've still got bills to pay.

It's very hard to sort of just shut down the dairy and say, I'm not gonna have any income for two months.

It's nearly impossible.

We'll, we'll get down to maybe 60 milking cows at our lowest point.

Maybe 50 milking cows.

Cal: Yeah.

With your, your heifers and your dry cows, are they getting moved as often as you move your milk Tom: No, I, I'd love to do it.

It's just too hard.

So we, we had dry land paddocks, so, so the milking platform is all irrigated.

We run, Cal: Oh, okay.

Tom: We run three soft hose travelers and plus we have some little bike shift sprinklers.

I'm not sure if anyone knows what that is, but they're fairly common in Australia.

So we have big, big boom sprayers and we irrigate around 70 hectares of, of pasture for the cows.

The heifers and dry cows run on dry land and it's very marginal as you can imagine, 20 inch rainfall with hard winters.

It's a fairly marginal country.

I think if I could move them multiple times a day, I could grow a lot of grass.

The time and effort is not really worth it.

So they do get moved every couple of days.

I put in a, you know, I put in the basic effort of moving them every couple of days and but if I could get some really high density stocking rates with heifers, I think I could grow a lot of grass on the, on the marginal dry land paddocks.

Because just by doing what we're doing.

We've turned paddocks that were just bare with no grass into, you know, somewhat, somewhat pasture paddocks, dry land, pasture paddocks.

Yeah, so I, I am seeing a huge difference by doing half a job.

If I could do a proper job, I'd think I'd see a huge Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom: Yeah, Cal: Yeah.

It gets down to that time issue because you don't have the ability to run them as all one mob Tom: No, yeah.

No, we can't.

We, we run all our heifers in one mob 'cause we're only carved once a year, which is a, back to the reason I do that.

So all our heifers running one mob.

So at the moment I've got, I got 90 rising two year olds and I've got about 70 or 80 calves.

And they all, they all run as one mob.

Cal: Oh yeah.

Tom, before we move to the famous four questions, do you have anything else you'd like to add?

Tom: I don't think so.

I think we've touched on most things.

There's, there's a lot of Cal: I, I, I tried to.

Tom: there's a lot of things I say that I'm not sure whether many people understand, but we'll see how we go.

It might be something different for your listeners.

Cal: But yeah.

We'll, we'll see how it goes.

for our famous four, same four questions we ask of all our guests.

At Redmond, we know that you thrive when your animals do.

That's why it's essential to fill the gaps in your herd's nutrition with the minerals that they need.

Made by nature, our ancient mineral salt and conditioner clay are the catalyst in optimizing the nutrients your animals get from their forage.

Unaltered and unrefined, our minerals have the natural balance and proportion to help that your animals prefer.

This gives your herd the ability to naturally regulate their mineral consumption as they graze.

Our minerals won't just help you improve the health of your animals, but will also help you naturally build soil fertility so you can grow more nutrient dense pasture year after year.

Nourish your animals, your soil, and your life with Redmond.

Learn more at redmondagriculture.

com Cal: And our first question, what's your favorite grazing grass related book or resource?

I Tom: Good question.

So, I employed a guy, I think I mentioned this before, about five years ago, and he put me on the.

Regenerative word that I'd never heard before.

He put me onto a book called Call of the Read, warbler by Charles Massey.

Um, Charles actually lives not far from me.

He's probably only an hour or a bit, bit over an hour from me, and I'd never heard of him until I read his book.

And that put me on this journey of realizing that there's this massive group of farmers, particularly in the Northern Hemisphere, on the same journey that I'm, that I've been on forever.

So Gabe Brown's book, dirt to Soil, another Easy read that between them two books, they've yeah.

That I would highly recommend them if I, I assume most people have read them, but if you haven't read them Cal: Yeah.

Or they're on there to read list.

I've read parts of both of them, but I haven't read 'em both completely.

Tom: Yeah, they've got a Charlie's books are they're fairly different style of books, but Charlie's book is good pretty much the whole way through Gabe's book.

I found that you sort of gotta take bits and pieces out of it.

There's a lot of stuff in there that probably wasn't relevant to me and but I still, it's an easy read and, and it's good to Cal: Yeah.

Yeah.

And both excellent resources.

What's your favorite tool for the farm?

Tom: Oh, good question.

I knew this was coming and I actually forgot about it.

I was thinking about books instead of tools.

I will say that I.

When?

When I first started farming, this is a bit of a story here.

When I first started farming, I used to have these cheap gumboots, right?

And I would lie in bed at night and my calves would ache, and I never knew why it was.

And then Gemma, my wife, decided to buy me expensive gumbo from New Zealand.

I can't remember the brand of them, but they had lots of cushion in them.

And when I hopped in bed, my calves didn't ache.

So I would say my number one tool is these comfortable gum boots.

They are, yeah, they've been a bit of a game changer for me.

Cal: I don't think we've ever had them listed as the favorite tool on the farm, but I would have to say it makes a world a difference.

Just depending upon what shoes I've got.

Or I had two pairs of tennis shoes and I, I bought one and it's supposed to be good for my foot, so it wouldn't bother me, and I wore 'em on the farm, and then I had my good pair.

And I've been wearing my good pair, which is actually the cheaper, the two brands, because I paid more for the one that I wear out and about when it's dry.

'cause I, I want it to not hurt, but I went and painted in a house on concrete and those shoes I wore on the farm, I could barely walk the next day.

And it's just awful when that happens.

That may be speaking to my age, but man, it was awful.

So in fact, I got rid of those shoes and I've been wearing the others all the time now.

Tom: Yeah, these are a game changer, especially you spend so much time walking on concrete as a dairy farmer and, and you don't really think about looking after your feet and your legs, but yeah.

Cal: Yeah.

That's, that's so important.

I know when I came home from college to dairy, I know my, my parents, they were about down with their feet and legs from standing on the concrete all the time.

Tom: Yeah, Cal: Our third.

Our third question, what would you tell someone?

Just getting started?

Tom: don't look at what other people are doing.

Worry about your operation, worry about what works for you, what you enjoy.

I got, when I first started farming, I got very caught up in trying to follow the norm, I guess.

And, but I didn't really particularly like farming like that.

I, I've.

I enjoy growing grass.

I enjoy cows on grass.

There's a push in Australia for for more feed blotting cows and putting cows on feed pads and things like that.

And then there was times during my farming career, I sort of went down that path trying to milk too many cows and trying to put cows on ous feed, but it wasn't really my skill level and I didn't enjoy it.

So I've gone back to particularly the last six or eight years, I've gone back to what I enjoy and what I'm good at.

And that is growing grass and having cows on grass for as long a period as I can.

Cal: Excellent advice there.

Yeah.

Just even when we look at people on the same journey, we believe we are on, we gotta be careful about they're in a different spot on their journey than we are.

So don't get caught up in that either.

Tom: especially there when, when you look at finances too and you see someone that's just bought a new mixer wagon and you think, oh, I should be buying a new mixer wagon.

But, you know, it's completely different financial situations.

Cal: Oh yeah.

Yeah.

And, and I get caught up in that sometimes.

My wife's like, Nope, quit worrying about that.

Yes ma'am.

Where can others find out more about you and what you're doing?

Tom: Yeah, I'm not really on social media.

I, I have social media, but I don't really go on it that much.

I'm in the, I'm in your group, but I rarely Cal: Right.

You're in the Grazing Tom: I mean, yeah.

Yeah.

And I've posted in there a couple of times, but yeah, I don't really, I don't particularly like social media.

So my wife runs, my wife runs a Facebook and Instagram account for our stud cows.

I, I think it's called Tango Holsteins.

She puts up very cute calf photos and photos of our kids with cows at shows and things like that.

So that's probably where you can find their business.

Cal: Oh, very good.

Very good.

Before we finish today, Tom, do you have a question for me?

Tom: I do, and I've been thinking about this for a while actually.

I would like you to describe your, if you were to go back into dairy farming, I would like you to describe what it would look like.

Cal: If I, if, if I had the money, could go back into dairying obviously I'd have a newer barn and a bigger barn because like you mentioned earlier about milking for an hour, that would be my goal.

That if my, if I'm getting to choose, I'm deciding how many cows I'm milking and that's gonna be based upon how much grass I have.

And I would get a barn that I can milk them in an hour, or I'd figure out about the robot milker.

And I've always loved, you know, moving the cows, doing the.

The lane to the barn.

You know, we never had a lane to the barn.

The cows went out in this pasture during the day.

Another pasture at night in that area where that pasture met the barn area where the gates they went through was always a mess.

And we, we put down so much rock.

Of course, if you put down that geo textile fabric, now you can hold that rock on the top, which is a game changer for our corrals.

But I wouldn't even worry about that now because of the virtual fencing and talking to people about the virtual fencing and halter being able to automatically shift your cows to the dairy barn.

I, I mean, I, I can always remember going out and going to get the cows or someone had to go get the cows.

Well, someone else is getting the barn ready.

If the virtual fence can do that for you, bring the cows up get you a nice.

You know, herring bones was all the fashion back then.

The parallels para bone, I think one, one company's got para bones that set 'em not quite a herring bone, but not 90 degrees to you, whatever.

I guess I would get used to that.

I actually love the side, the, the full side and single entry exit, but you can't milk very many cows through there.

But I like seeing the whole cow, so I guess I just have to get used to a, a parallel or a herringbone to do it.

I do a swing over barn.

We did low line milkers, but I think you can get more through there if you've got a bigger barn and swing.

Then the grass is for the breeds of cattle.

If, if this is all make believe, I would choose some unknown breed or some.

Rare breed to milk.

Granted, I, I think you, I have to, depending on your market, I mean, you got hostings, but you gotta get 'em moderate size so they can handle grazing.

If you're doing more of the specialty market, the jerseys really excel there.

But you know, if I'm gonna do hostings, it's gotta be red hols.

It's gotta be a little bit different.

Well, of course I like the air shires and the Milky Shore horns.

I've always loved Dutch belted.

The line backs are always great.

Probably have to do a hosting base and then just play with those breeds some you all have milking shore horns down there, the auroras Tom: Yeah.

Yep.

There's a few farmers around here, a few farms around here with full Illawarra herds and they date back to genuine Illawarra cows from 150 years ago.

It's very, very old stud breeders have the Illawarra cows.

Ca Cal: And I think those genetics have been brought into the us.

Of course, they're, I'm pretty sure just absorbed into the milking shore horns here.

And and, and that's one thing, since all the genetics have been host of Holified, you know, they've, they've added a hosting genetics to milking shore Horn, air Shire, all these breeds to increase their production.

I definitely would prefer the older type and not worry about producing so much.

But that, that's all depends on how much money I got in a bank account, because you gotta make money.

Tom: it's always good to dream.

I always have these dreams about if if I was to start again, what would my farm look like if I didn't have any debt and things like that.

Cal: yeah.

Yeah.

Have, yeah.

I, I do, I I love the New Zealand type of milking sheds that's just got the roof.

Our environment's not real conductive to that, but that'd be, you know, if you had garage doors on the side of it that you could open up during the time of year, you, that is possible.

That'd be really nice.

And yeah, I have a flush system to clean it all quickly.

Yeah, it, you know, I remember high school, obviously this doesn't make me very popular.

I'd read so many dairy magazines and I'd designed parlors all the time.

I, I had notebooks full of parlors and different types and different layouts.

I can remember telling my parents about it, and I'm sure they thought I was crazy at the time.

And I'm even shocked.

They listened to me for however, how many different parlors and then I even.

This is really going back.

I had a in television video game system, but they came out with a keyboard and you could run, no, actually I had to take that back.

We had a Vic 20 keyboard that would plug into the TV that you could write programs for.

So I wrote a program so I could cross breed dairy cattle and it'd draw me a pedigree of, of the breeds that in there.

And then it averaged all their expected milk production and butter, flat fat and stuff to come up with this composite.

That was the, the dairy cow I'd breed.

Yeah.

Yeah.

I, I love that exercise, Tom.

That's a question I haven't been asked.

And I, I love the aspect of dairy.

You know, of course I'd like to have a little store at the road that I could sell all my products through.

Tom: we, yeah, that would be one thing we'll venture into one day is being able to process our own milk or, or even just a, a small portion of our own milk.

'cause we live on this main road.

We get lots of people that would, I, I believe, would love to call in and just buy two liters to Cal: Oh, I, I think so.

And I, I love the idea of making cheese as well, and other dairy products.

Tom: Yeah.

Yeah.

Cal: Yeah.

Well, that's a good question, Tom.

I really hadn't thought about it, and I'm thinking I didn't, I gotta round out my answer Tom: I know you've got a deep love for dairy farming and milking cows and things like that, so I knew you'd enjoy that.

Cal: oh yeah.

That, that was a good one.

I did enjoy it.

Tom, Tom, I really appreciate you coming on and sharing with us today.

Tom: No worries.

Thanks for having me.

It's good to, I dunno, I like these sort of podcasts.

They're, they're easy to listen to and it's lots of different, lots of different angles at regenerative farming, I think.

Cal: we good.

We, I hope people enjoy it.

Tom: I'm sure they do.

I enjoyed the conversation with Tom.

I always enjoyed the opportunity to talk about daring, especially in a place I've never been.

It's very interesting.

We gotta talk a little bit about breeds.

As you know, I always love breeds.

The other thing that I think was interesting, he brought up the fact when he heard about Regenerative and looked into it, he's like, oh, this is what.

I've been doing for all these years.

You know, I can remember when Greg Judy named his channel Regenerative Grazier, Greg, Judy.

I'm like, what's that even mean?

Then dug in deeper and it's what I'm trying to do here, trying to be regenerative.

And as we mentioned on the podcast, Tom and I mentioned lower inputs, lower costs, uh, make more profit and.

The leave that land in a better shape than we've had it before.

And I think it all goes hand in hand, which it's amazing that it does.

But I did think that part was really interesting and I really appreciate Tom coming on and sharing.

Cal: Thank you for listening to this episode of the grazing grass podcast, where we bring you stories and insights into grass-based livestock production.

If you're new here, we've got something just for you.

Our new listener resource guide.

Is packed with everything you need to get started on your listening journey with a grazing grass podcast.

It gives you more information about the podcast about myself.

And next steps.

You can grab your free copy at grazinggrass.com slash guide.

Don't miss out.

And Hey, do you have a grazing story to share?

We're always looking for passionate producers to feature on the show, whether you're just starting out or have years of experience your story matters.

Head over to grazing grass.

Dot com slash guest.

To learn more and apply to be a guest.

We'd love to share your journey with our growing community of grazers.

Until next time.

Keep on grazing grass.