Episode Transcript

I really want to know what inspired you to start the podcast.

Yeah, I wanna get to that in my second deployment.

I'm in this, this war zone and I'm just thinking to myself like, I'm like, I don't know if people in America understand that this is what it's like when you're gone.

This often what it does to families, and I hadn't deployed many times like you have, but I've been gone enough to appreciate it.

And this is 20 16, 20 17, where podcasts are picking up.

Mm-hmm.

And I was like, what am I gonna do if I could sit down and talk to people like this and share their stories so someone understood what it was like, the actual pain that goes into it, not the movies, but like all this time where you're alone and you're missing all these events and you're almost dying and you're watching friends die.

That's what I want to do.

That's where the podcast came from.

Like, I have a very genuine curiosity as I interview people, but I have tremendous respect for guys like you who are on the ground, being in the air, watching you guys do what you did.

I never had to go kick in a door.

I didn't have to get in the stack.

I didn't have to breach for days on end.

And so that it, it is coming from a place of genuine curiosity and admiration as we're doing these interviews.

Um, I mean, for me, I wanted to help people and I, I am positive we have, and I hope that.

People hear those and it makes 'em stick around another day somehow.

I think there's so much is I don't think that people join the military for a, a parking spot at Home Depot.

Right.

You know, like, I'm not, that's not why.

Yeah.

You know, men and women do that.

You know, I think that there is this greater call to service.

There is a, a primacy that we as a society should put on, on serving one another.

I think that really cool how you've done this.

Have you've established that.

Um, and, you know, I just, the impact that you had with this is so crazy.

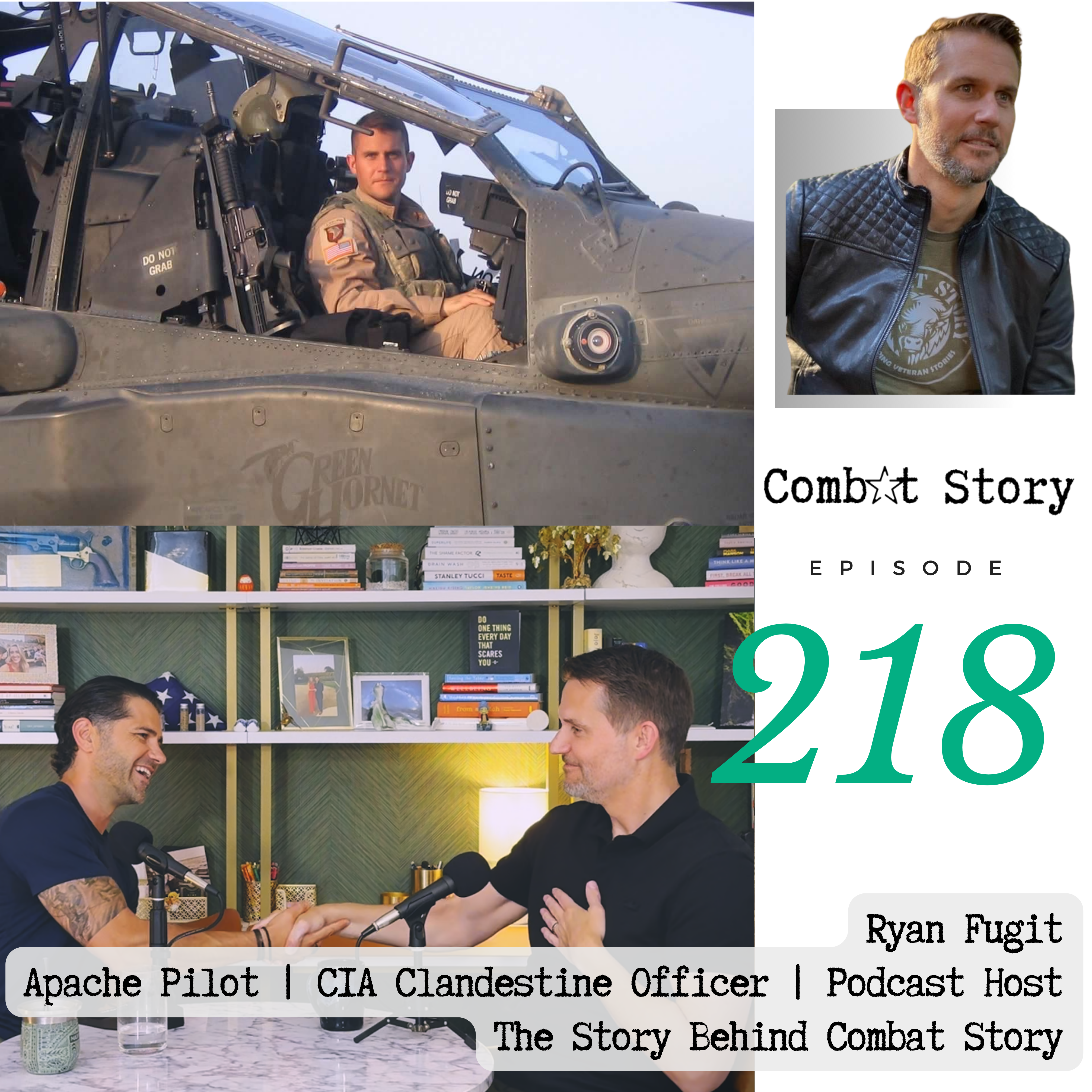

Welcome to Combat Story.

I'm AJ uti, a retired marine force recon scout, sniper, and marine gunner with 21 years of service, multiple combat tours, and a lifetime of lessons learned in the arena itself.

On this show, I sit down with warriors from every front line to uncover what combat truly feels like and how it shapes the way we see life each other and ourselves.

This is Combat Story.

I wanna start this, this interview off with thanking you, um, for really everything, uh, that you've done.

So you and I met, um, at a, a gala where I was speaking up in Los Gatos.

Mm-hmm.

And it was the Los Gatos Veterans Foundation.

Yep.

The Los Gauss Veterans Foundation.

And so I was asked to be a speaker there, um, and, and got all, you know, dolled up, had a little tuxedo on Right.

You know, had my little tie that, which I had to tie my own tie on that, or a text that is really not a click on.

Not easy, not easy.

Had to YouTube that one.

And so we, you know, I give my kind of speech, you know, I go in time to talk to the audience.

I actually feel that I didn't do a very good job on just blown smoke.

Literally, everyone was in tears, literally.

I really appreciate that.

Not me, but, you know, and so, uh, you and Val, uh, came up to me afterwards.

Um.

You are a very different demographic than a lot of veterans organizations that I, I have seen generally the veterans organizations are a little bit longer in the tooth.

Uh, a little grayer in the hair.

More experienced, you have more experience, right?

Yeah.

Um, and so having a couple walk up to Sarah and I at the end of that event, and, um, you, one, you guys had done part of the silent auction and purchased a plain air pastel or plain air oil, uh, or, uh, a paint or a painting, uh, of which I noticed because my mother was an artist.

So I was fascinated by that.

And you came up to me and you, um, you asked me if I, you know, hey, I run a podcast, I run the show.

I would love to have you on it.

And, and you said your story was really impactful and I was really appreciative of that.

'cause I felt terrible.

I felt miserable because when I, sometimes when I go and I give that story and I talk about that, I want to do as much justice to that as possible.

And I totally felt I just didn't do it, uh, enough justice.

And then you came up and said, man, I'm really inspired by this.

I wanna bring you on.

Can I interrupt real quick, please?

Um, I mean, this is in the.

Shameless plug, but like, this is in, in your book, dark Horse.

Right?

But the way that you delivered this story, so this is a veteran annual gala.

Like the one thing, a big event for this veteran foundation.

You're the guest speaker.

This is like prime time for that night.

You deliver this, um, story about losing your best friend in combat.

And it's all framed around the flip of a coin.

And like even the storytelling was so nicely done and well thought out.

And for all the men and women in the crowd, everyone was drawn to it because of the way you told the story.

I think that was very easy for me to see, like how natural you were at storytelling.

And then that happened on the podcast, obviously.

Anyway, I just wanted to, like, that story is in the book, but that hit me hard and it was all about the flip of a coin.

I think that the idea behind that story and the flip of the coin and why I've remembered it and why I've continued to tell that was, you know, yeah, there's some survivor's guilt, right?

Is the idea that something as as, as, um, as easy as a 50 50 chance as to why Matt got the mission and I didn't get the mission.

Um, it, it, it, it shows me, I think the fragility, uh, of it all sometimes how my life is ch is, is a, a series of different chances that we all take.

And then I remember sitting in the interview with you at your home, um, and I was exhausted at the time.

We came over late, over late, later in the evening.

And I remember going through that process with you and you were so welcoming.

And so what I found about you as a interviewer was you were genuinely curious, uh, about the story itself.

And you wanted to know more about not just the story, but what made me tick, why it impacted me, how I wanted to shape the rest of my life because of, of this incident.

Mm-hmm.

And so fast forward, so starting with the end is this took me, you were the one who sat me at the coffee shop and said, dude, I never do this.

You need to write a book.

And I, no, I don't want to do this.

This is, I appreciate that, but you know, I, this is, this is where I'm at.

I've been interested in the idea, but I've never really wanted to take it to fruition.

And you are the person that lined up all of the characters needed in order to, um, facilitate and really empower me to, to tell my story on paper.

And now we are, uh, full circle.

We are sitting where the book is currently at DOD review, uh, and going through the, the right process to be able to publish something in a sensitive environment.

And then you gave me a call.

Uh, I remember I was in Japan.

I was following Sarah around for work.

And so I was in Japan and I got this email from you and you said, Hey, I got some stuff I wanna talk to you about.

And then you sent me this really long email.

And in your most you do the same thing I do is you wrote, uh, in this email, I, you know, you were almost very nervous, it seemed like, in the email to ask.

And you said, Hey, I've been, you know, ruminating over this for a long time.

Right.

And I would like to know your thoughts on potentially taking over as the host of the podcast.

And then you immediately apologized for asking me in the email, right?

Yeah.

And it was very much the same way that like, I'm sorry, you can tell me to go kick rocks, right.

If I need to.

And, and then, and then you went through this.

And I had never ever thought of that before in my entire life.

And so I want to know.

Before I take this thing and continue to run with it and try to do as good of a job as you have done with this, I have so many questions as to what led you to this point.

Um, for me, I want to know about your background.

I wanna know what led you into service, um, and, and where you were at.

So I think the, the, the inflection point for a lot of us was nine 11.

Was nine 11 the same inflection point for you as it was for other service members, or had you already identified that you were going to join the military?

Yeah, I had already identified that.

So nine 11 happened when I was a senior in college in DC so, you know, a little closer to home because of the Pentagon getting hit.

Sure.

Um, but I was already in ROTC for three and a half years at that time.

Okay, cool.

Um, so my old man, as many people listening who have heard me talk about him and he's been on the show and actually that was a really special interview.

Um, you know, he flew Hueys in Vietnam and then he spent decades in the foreign service as a political officer.

But, you know, I just grew up knowing I was going into the military.

That was the expectation.

It was gonna pay for school, good opportunity and a lot of adventure and fun like most young, young men I think are looking for.

So I was already committed, but I will say things changed after nine 11 because on campus.

Going to ROTC pt and like we'd have military science classes.

It was somewhat laughable, I would say, like a little bit of a joke as people saw us walking around.

I think after nine 11 and after like these Green Berets on horseback and the fire power and all of these things happening, things really seemed to change and there was a lot of respect.

And I don't take it for granted after hearing what my dad and his generation went through coming back from Vietnam, which is a very different story, obviously.

So anyway, for me it was nine 11 was more of a, you know, further stoking this interest that I had, did everything.

The way that, if I look back to that timeframe, I, I was only 17, uh, 16 when nine 11 happened and 17 when I started to, you know, the process to join.

It just felt the, the world felt somehow different.

America felt somehow different.

Like we knew it was like, almost like we were, I I, I would always, uh, associate as like, we were like crouching before a jump, you know, before like we knew that we were getting mm-hmm.

We were loading before we kind of leapt into something.

We didn't know what something was, but there was this almost like sense of urgency or sense of duty.

Did you, did that change in you when you were like, Hey, senior in college Right.

You know, cruising through Yeah.

ROTC, it, yeah, it was, there were a couple things that happened right after nine 11.

So I, I played, I, I say this loosely.

I played football at Georgetown, which, um, like I hardly got on the field, but I was part of the team.

Right, right.

And we had, I think we had to postpone our next game after nine 11 and we played it the following week because it was playing a school in Jersey City.

Oh wow.

So like right up in where Ground zero, you know, very close to ground zero.

Um, and a lot of the guys on our team were from New Jersey and New York, and.

You know, the, the fire department hats, the NYPD hats that would come out after that.

But going up to New York shortly thereafter was a big deal watching the smoke come off the Pentagon.

Huge deal for me.

Like I rode my little moped close enough to see it, but then they were kind of stopping people from getting too close.

And then in December of that year, Mike Span, who was a former Marine, and then, uh, CI, a paramilitary officer, was killed in Afghanistan, widely regarded as the first death in the campaign.

And they had his funeral in Arlington Oh, wow.

At the time.

So I saw in the Washington Post that, and I would read this voraciously every day to see what was going on with the fight.

And they announced anybody could come to the funeral.

So I went and it was amazing.

I mean, it was freezing cold like no leaves on the trees in, in Arlington, you know, Northern Virginia, all these people out there, you see his wife.

Um, a lot of people cloak and dagger 'cause of the CIA side and a lot of former military.

Sure, of course.

Um, and I remember asking a, a guy standing next to me, you know, this.

Everybody in the military knows this.

This is when I learned it.

You don't call somebody an ex-Marine, it's no such thing.

And he's like, no, he is a former Marine.

Yeah, yeah.

You know, um, we are a proud bunch.

Yeah.

And, and it wasn't antagonistic at all.

It was just like teaching this young guy something.

But those moments really stuck with me.

Um, post nine 11.

So the crouching moment you talk about, like, I could feel that, but oh my gosh.

The hesitation for me of like having watched the Gulf War and then Bosnia mm-hmm.

And the fear of not getting into this fight and what that would mean for an officer's career in the military scared the hell outta me.

So I really wanted to get into the fight and I had already selected aviation, which has a very long pipeline.

Right.

And you potentially, I could be in this pipeline longer than the war lasts.

Right.

That is everybody's fear at the time.

And mine in particular with aviation, it is one of the most hard to explain, um, phenomenon to people who are saying, well, do you enjoy what you do?

Um, I don't know.

Yes.

But I also like you, but so you willingly want to go to fight?

Yes.

It's what I felt called to do.

It's what we all felt called to do and I would feel terrible if I missed it.

Yep.

And it's weird 'cause we know we're stepping into potential carnage.

We're, we know we're stepping into, you know, loss of life and we're gonna be changed forever.

But there is no way that I'm going to allow this to happen and not be a part of it.

Yes.

It's like this weird calling.

I, I couldn't, I couldn't describe it and some people I don't think have that and that's okay.

That's interesting 'cause doing this show, and I'm sure you're gonna get many more of these questions as you do this, but I'm sure you get a lot already given your background.

But people who will ask you like, Hey, I'm thinking of getting into the military, should I or not?

And there's all different kinds of answers you give them.

Sure.

But I do think that's one of 'em, like, if you feel like you have to get in and do this, that's a pretty good indication.

Yeah.

If it's not like very passionate, I will do almost anything to get in there to that fight.

Maybe it's, you know, it can be right.

Might not be.

But that is something that I think is true for many of us.

The military's, like the Marines had a famous saying for a long time, I think it was seventies and eighties, it was like, we didn't promise you a rose garden.

And it's, and it's, and it was like this tough guy campaign, which I actually think was a very successful campaign.

However, you're right.

If you're not going to, like, that's what I do is when I talk to young men or young women who wanna be able to join the service.

That's great.

And I think it's phenomenal that you sh you should have the apprehension, you should have the fear, the potential desire to do so.

But if you're not going to dedicate every fiber of your being into this and to the service, and to the service of others, and to the profession of your craft, don't do it.

No.

Uh, because it's not going to be a good experience for you, uh, you know, regardless.

No.

Okay.

So nine 11 happens.

Did you get a chance to go to New York City at all during this timeframe?

Yeah, I mean, we went, we went right up to play this game.

Like we were on a bus, um, with the football team from DC going to through New York.

And I, I just distinctly remember that now.

I didn't walk around ground zero or anything, but just you, you know, you could just feel it in the air that the national Anthem was electric.

Um, all these, like, you know, it's a team of 70 guys, at least 30, 35 of 'em grew up in and around Oh yeah.

Jersey and New York City.

So it was personal, so it was really personal.

Yeah.

Uh, one of the former members of our football team was in, so he had graduated in 92 and he died in the towers.

So they've got, his number is, you know, given out every year or two, a standout player.

Oh, really?

Yeah.

It's a, a new tradition that they've had and several guys, this is, this was interesting to me.

Um.

Uh, I was the only one in ROTC at the time of 70 guys, but of my graduating class in the class, maybe one ahead and two behind me, probably seven or eight guys went into the military who, if it weren't for nine 11, probably one and a half.

Interesting.

That would be my guess.

Um, you know, a couple of 'em are still serving, but I, I think that it completely changed so many people's lives.

Not a lot of people go to Georgetown to then go into the military.

Okay.

What's a normal pathway within Georgetown?

Is it Poli sci?

Oh, totally.

State Department, USG Agency.

Um, UN anywhere you can go abroad and not make a lot of money except for the military.

So our ROTC class, we had nine people graduate, um, which is fairly small right.

For, it's a, not a huge school, but that's fairly small.

Okay.

So you mentioned, uh, aviation.

Did you have an aviation contract, uh, when you were in ROTC?

I don't know how the Army works as far as that goes.

I also didn't go to the OCS and ROTC program, so without boring people, the, it's very, it's just a competitive process like anywhere in the military as you're going through ROTC and at the end they rank order everybody in the country, and if you're in the top 10%, you get whatever branch you want.

If you're in the bottom 10%, they're gonna assign you to good branches.

So that.

Good branches, get people who aren't as great.

I have so many jokes before right now.

Gosh, that's that.

I, I'm, I'm being good.

This is the Army Marine jokes.

Alright.

And then in between, it's kind of like needs of the army.

So I, I really wanted to have my choice of, of where I could go.

And in the end, I still remember the night before it was like, am I gonna go aviation or infantry?

And I, I would've regretted it either way.

Like my old man had flown, I have a brother who flew.

Um, but a lot of what I grew up watching and the books I read the Dick Marcenko books mm-hmm.

And Tom Clancy and everything.

It's like, it's infantry guys.

So in the end, I, I chose aviation.

And again, you know, had I gone infantry, I'm sure I would've regretted not being able to talk to my old man in this way.

Like, we both went through very similar experiences.

Really?

Oh, it's super similar.

Just different technology.

Um, so like he and I are closer, I think because of that.

But at the same time, and you brought up the curiosity that I have on the podcast, which I appreciate that it comes through.

Like I have a very genuine curiosity as I interview people.

And I haven't interviewed a lot of Apache pilots because I, I have done that.

Um.

I have tremendous respect for guys like you who are on the ground.

And I never had to do that.

I never had to go kick in a door.

I didn't have to get in the stack.

I didn't have to breach, I didn't have to sit out in the middle of nowhere for days on end and not shower.

Like maybe I went two days without shower in down range.

Uh, this interview was over.

Uh, I mean, serious school for me was like, wow, we really stink.

You know?

Um, but I, I have tremendous admiration being in the air, watching you guys do what you did.

And never having done that, so that it, it is coming from a place of genuine curiosity and admiration as we're doing these interviews.

So, and to, to not get super, you know, you know, self-congratulatory, you know, or, you know, fawning over you.

There is nothing that compares to the feeling.

Um, and I can't speak for everyone, but I can speak for me.

Just a quick word from our sponsor, veterans help group.

We'll get right back to this episode.

Some of you may be struggling with things today that weren't there before you deployed, or maybe you're noticing this in a loved one, a spouse, a son, a daughter who went down range and came back.

A little different trouble sleeping, dealing with pain, stress, mental health issues, and maybe a whole lot more.

The question is, what are you gonna do about it?

Let me tell you, you signed that contract.

You served your country, you earned your benefits, and that's why I want you to do yourself a favor and call my friends at the Veterans Help Group today.

They're here to help you get your benefits.

I've navigated the VA system to get my own benefits, and it can be hard at times, and the Veterans Help group makes it that much easier.

The veterans help group knows the VA because VA disability is all they do.

Whether you've been denied or appealing or filing for the first time, it doesn't matter.

These guys know how to get you approved for 100% of the benefits you deserve.

They've done it for thousands of vets just like you and your loved ones who served.

Go to veterans help group.com or call veterans help group at eight five five two three one.

6 1 4 4.

And tell them your buddy Ryan and AJ from Combat Story sent you.

That's Veterans help group.com.

Veterans Help Group does not guarantee outcomes and past performance does not guarantee future results.

The company is neither a law firm nor affiliated with any part of the US government, including the va.

And now back to this episode.

When we're on the ground and we're in a hairy situation and I hear the of some sort of rotor coming in Yeah.

That we're gonna be okay.

Like that for us does so much to us because oftentimes video games don't cover it.

Like, we can't see bad guys don't stand out in the middle and like wait for you to target them like they don't want to die just as much as I don't want to die.

And they work very hard to remain hidden and clandestine until the moment.

And so oftentimes we can't see these people, uh, you know, it's Bush's or things lighting up or they're maneuvering.

They're a smart enemy.

And so when we had pilots come on and we could hear the wmp w of the rotors, specifically rotors, because you guys can loiter on station and then you guys add this dimension to the battlefield that when I worked with Apaches, or when we worked with Cobras or Hueys, they had this ability to almost hunt with us.

And sometimes I would almost make it akin to, you know, uh, like foxes, like when we were on like a big hunt and we're hunting whatever game it is, and then the foxes or the dogs would go out and, and bring the fox out, right?

You know, and kind of flush them.

For us, that was huge for us because it was this, uh, almost like to make a football reference, uh, that my little ass was too, uh, too small to make like a linebacker you guys would, or a, or a free safety, right?

Is you guys would plug holes in the defense, right?

Or you guys would think at a, at the game at a different level.

Because now I realize hindsight is, it was by design is I'm looking right here in the front and then you guys are able to be, you know, literal angels on our shoulders.

Uh, so thank you again for, for that.

I just really, to any pilot out there, uh, you, there is never a, um, a draw or a comparison, you know?

Yeah.

We give you guys, you know, crap.

'cause you guys can eat ice cream at the end of every day and there's always gonna be that, but it's, it's comes from a place of, you know, jealousy and love rather than absolute animosity.

Yeah.

No, I appreciate that.

And I do feel.

Especially having done this podcast and interviewing 200 vets, like everybody's got one of those stories about, like this one time when I was in this situation and all of a sudden there was air cover.

Yep.

And this is what it was like.

Um, and I also felt there wasn't, um, and I don't know if what this is like for guys who have done this on the ground, like there was no real, uh, competition of machismo between me and a ground pounder.

Like maybe, I don't know if, if a seal meets a recon guy, it's like, yeah, were you really tough?

Yeah.

Like for me it's, I didn't do that.

And then they'll look back and be like, there it was just mutual admiration.

So I feel like I had that, but truly I'd never had to do the, those really hard things of going in and, and looking that closely at the guy that we're about to take out.

Um, fast forwarding slightly, we do these career course, you know, advanced courses through the, our career progression most of the time.

Like I, I learn aviation basics at the aviation basic course, and then I'm supposed to go to the aviation officer or whatever, it's the captain's course.

Mm-hmm.

Um, you could go to different branches.

Uh, for training for your advanced course.

And so I chose to go to the Infantry and Maneuver.

They called it the Maneuver Captain's Career course and Triple C Yep.

At Benning.

Mm-hmm.

So there were probably two aviators in this class of a hundred plus and Marines, which was cool.

So it's an Army class, but you know, there were some Marines we need to bring the physical standards up.

They brought Marine Marines and literally the number one grad was a Marine, which I was like, come on guys.

Um, but I went there so that I could understand how you guys think on the ground, truly just how do you move through, how do you get ready to cordon off a target?

Um, all the logistics that go into it.

And it was so helpful when we were down range for me to just understand that beyond knowing the guy there, which a couple times I was supporting some guy who was in my class, which was great.

But just how you guys did things was so, so helpful.

I think from my perspective when dealing with aviation assets, it was, um, it was really, it was really nice to know that.

When I was working with a pilot trying to solve a problem, whatever that problem was, that it felt like a lot of the pilots wanted to help you get that missile off the rail.

Yeah.

It wasn't like a lot of like, well, we're gonna be risk adverse and make, and, you know, we don't, it was like, and we'll take any excuse to get that thing off the rail.

Correct.

Especially, I think as the war progressed, we got a lot smarter in how we did it later on, but it was very much like, I remember pilots forgive the term, I don't know a better one, but almost like they used to pimp us for information.

Hey dude, you need to tell me this.

Give me, and 'cause stuff's going haywire.

Right.

You know, um, and I'm trying to figure out which way is up.

Right.

And you're over.

You've got space and time, which I think is good.

Yep.

And you're loitering at a, forgive me, is a IP or BP battle position?

An ip, yeah.

Our kind of one of the points as we're coming in, but we, we often wouldn't even use that.

Okay.

Yeah.

So when we're doing a, we're very rudimentary, like we'll have them, you know, Hey, they're off our right shoulder here waiting for snakes to bite, is what we used to say.

Yeah.

Because we have cobras.

Yep.

And so our term was, Hey, we're waiting on snakes to bite.

That was always like, eh, like a super cool thing for us.

That is cool.

Say um, you know, uh, okay.

So.

Absolutely fascinating.

So you go through, uh, you've gone through your aviation program.

How does the selection happen when you're getting your individual platform that is also super competitive?

So, aviation, infantry, armor, typically very competitive branches to get.

So once you get in them, you've got a lot of heavy hitters in there.

And, and there's no special ops track, right?

So it's like everybody's here first before they can go special forces later or ranger.

So within aviation, you all go through the, the basic aviation courses where you just learn literally how to hover, how to fly, how to navigate, how to go up into the clouds, which is pretty scary, um, and not die.

You go through all that and then at the end of that eight, nine months, there's a ceremony where 30 guys are in a class, 30 guys and gals are in a class and they basically on a board, they just put up, hey, the army has these 30 airframe available.

So it'll, at least back then, and it's probably very similar now, it's like two Apaches, one or two kis, a ton of black hawks and a handful of Chinooks.

Mm-hmm.

And then one maybe like, uh.

Fixed wing VIP platform.

Oh, okay.

Okay.

Um, and so they just say, number one in the class, what do you want?

Number two, what do you want?

And they just take it off the board.

So it's very, these are people you've been with now for like eight or nine months, sweat through things with, and, and it's just competitive at the end.

And you have an idea of like, oh, I know Nick over there.

He wants to go Blackhawks.

All right.

Those guys, they want dogs.

Are you like competing in your mind?

You're like, okay, oh, you're all competing through this because you're like, I want whatever that thing is.

And you're like, like, okay, well this guy messed up that thing, so he's probably outta the running.

Right.

You know, so you're all compet, which jockey?

I don't know if that's good or not.

Like, but we're, you know, still very good friends with all these guys.

And then at the end it's like, all right, what do you want?

So for us, Apaches went one and two right off the board.

And then it was a Kiowa, so like guns recon, and then it was Blackhawks and Chinooks throughout.

Like some people want to do Chinooks, like heavy lift.

Mm-hmm.

Other guys wanna do black hawks.

It sets them up nicely for one 60th on the special ops side.

Um.

So I, I was like, I try, I try really hard in that course and got one of the top two picks.

So I was very fortunate.

I feel like a shithead every time I tell this story, but it it, like, it, it was important to me if I wasn't going to infantry that I was as close as humanly possible to supporting guys who were on the ground.

Put yeah, put, put everything into it.

Okay.

So then you, you kind of glazed over it there.

I did, yeah.

We're gonna keep glazing.

So did you take number, I'm gonna ask you to point blank.

Did you take number one outta the class?

I did.

And I'm gonna have Juan edit this out.

Um, no, it was funny 'cause I had two of my friends come up, uh, from two of my friends from high school came to our graduation and then they announced it.

They're like, Hey, our number one grad is gonna speak Ryan Fut come up here.

And they were like, what the, how'd he get that?

So it, it was cool there, but there, you know, I, I had no animosity with any of the other guys and so a couple of 'em now are, uh, full, full bird colonel brigade commanders.

No way.

So it's pretty cool to see them having moved through the ranks.

Random question.

Do you have any, uh, like opportunity to meet up with these guys that you were in flight school with that you can kinda like come and see their squadron and like hang out at their squadron kind of thing and be like, oh wow.

You know, man, this is such a good question.

Like, this is, uh, just to admit this openly, I have so much imposter syndrome and so much guilt for having left the military.

What, um, so.

All these guys, like if they called me right now and they're like, Ryan, I need you.

I would be there in a heartbeat.

But I feel like I left them when I left the military and they, they're 20 years in.

Sure.

You know?

Sure.

Like they did multiple deployments.

I did one in the Army.

Um, so I feel like I don't have the, uh, right.

To be in the same room as them, let alone like go see their squadron.

And I know that is irrational, completely irrational.

I don't think they would feel that way, but humans aren't necessarily rational beings.

Right.

And there are, there are probably three guys who I've not interviewed who were in my unit when I was down range, who I would kill to interview.

And I hope I do one day, but I don't know if I can even ask them to do it.

Wow.

Okay.

I, for being an opposite side of it, um, I think, like the first thing I wanna say to that is you're, you're absolutely high.

Uh, that is not, I, I know that is not, I know as I say it out loud, anybody who understands this, this world knows that you didn't, you didn't take a knee, you didn't, you didn't drop out a formation.

You did your time, you did your service, you did it honorably, and then you moved on.

Yeah.

And then again, like you moved on to the clandestine services.

I did, but not right away.

I had a slight break there.

Yeah, sure.

At the, you still were, were working, you know, towards, I, I don't.

I struggle to, well, I actually have a lot of conversations with veterans who didn't get to combat, um, yeah.

Who, uh, or who got to combat, but were in support roles.

We, my own personal challenge that I face with this is that we have a lot of this, um, societal pressure that we focus a lot of times only on the 20 year special operations guy or gal.

They, and they should be Absolutely, you know, held up and, and respected and revered.

Uh, but I don't want to do that at the point of where we're, where we're discrediting the service of other people.

People.

Totally.

Yep.

One of the things that I learned, now, again, I was a cocky, you know, 20-year-old sniper at one point who thought that he was, you know, God's gift to the infantry.

Um, right.

So I I, anyone that had to deal with me at the time, I, for, you know, please forgive me, I've grown.

Um, but I realize now in hindsight that, and through a lot of mentorship was that we are merely a, a portion of the equation.

There's so many people to it.

Totally.

Yes.

So I have never in my time looked at you and everyone like jumped did one deployment.

Like I've never No, I know.

And I don't think anybody would.

And that's like, it's almost like it's, I suffer from the same imposter syndrome.

Yep.

And again, I, I tell you as taking over this podcast, uh, you know, as the host of this thing, we're co-host however we want to, you know, deli.

Yes.

Thank you.

Uh, as we wanna delineate.

You've mentioned people that you're like, Hey, I wanna get you in the room and interview this person.

I'm like, uh, do you wanna bring someone that's better, uh, more qualified?

Right.

You know, like, I feel the same stuff.

Right.

You like, I actually think that's kind of a good trait.

I think that you, what I, and I, and I know that I'm talking a lot on this, on this subject and kind of making you uncomfortable with it, but that's, to me, I want to really nail down on the fact that it, you should be proud that you took honor grad from that course, or the number one graduate.

I know.

I know.

However, I completely, completely understand the stigma because we all saw the guy that would check in and be like, I'm gonna, you know, like, I'm gonna be number one here.

And you're like, whatever.

Right.

You know?

Yeah.

And so we don't want to be that guy at the same, at the same point.

It's so hard because again, like that's, so first of all, you got selected for ROTC, which is not easy to do.

Then you got, so that's not that hard.

Yeah.

Then you got selected to go aviation, which is not that easy to do.

And then in aviation, you got selected to do one of the two seats for the platform of the age 64.

Mm-hmm.

Do they still call it the long bow?

So I went into the Alpha model, which is slightly older, and then right as soon as I finished that, they sent me to the Delta model, which is the long boat.

Okay, perfect.

Alright, so then they put you in the, like you, the, the, the rare air that you were breathing because of your work ethic, because of your dedication.

Like again, I'm, I think when I look at this is I'm, I'm sure, and I would love to explore, was there a lot of, did your father put any pressure on you or was what like, like actual pressure?

Like, hey, you know, you gotta do this, or you're out of the family, or is it like that you wanted to live up to your father's legacy?

Was there self-imposed pressure?

Yeah.

Do you have, you know, any, were there any physical conversations that happened?

I should disclose?

So if Val were here, my wife, she would say a hundred percent.

Ryan was doing this to make his dad happy.

I, I really don't think that's the case.

And my dad's story and mine are very, very similar.

Even like until six years ago.

So like, he played football at University of Vermont on a scholarship, did ROTC, went to Vietnam, flew Hueys in combat as a platoon leader.

Um, got out career in the foreign service.

I grew up, went to Georgetown, played football, ROTC, um, flew helicopters, went down range as a company commander, so slightly different.

And then went into the CCIA A, which is like my.

Very similar.

Yeah, very similar.

I embassies abroad.

Um, so there is a, I can't discount that that's the case and I don't know how just growing up like that influences those things.

Sure.

But when I was little and we were living in Africa, that's one of our assignments in Zimbabwe, and I had a ton of time to myself as you did in the eighties.

And it's just like, get the hell outta the house.

You're like, all right, let me go.

I wasn't doing other stuff.

I was like dressing up in camo and Oh yeah.

Pretending to attack something.

And the toys I played with were gi jokes a hundred percent.

And during the golf war, I got these baseball cards that were like, different airframes.

Oh yeah.

And seals and marines and like these different units, NN none of that was handed to me.

That was just something in the culture I grew up in that was like that.

I would ask my dad occasionally like, Hey, tell me, tell me about Vietnam.

Like, tell me a story.

And he had some good ones and it was never told to me with this like era of embellishment, he is incredibly rational.

Very rational.

No, uh, not a ton of emotion in there.

So it was just like, this is what it was like, matter of fact.

So I, I guess I can't answer it psychologically.

There's probably something there making my dad happy.

But there was no like, you need to go do this.

I mean, there was a little bit of if I want to go to school, this is gonna pay for it.

Sure.

So there was that, but it was all pre nine 11, like we didn't know we were going to war.

It could have been four years and out.

I want to dig back on something a little lighter.

So you mentioned GI Joes and, and mm-hmm.

Pop culture.

Favorite movie that you think pushed you into this service or, and then your favorite GI Joe.

The two things that pop into your mind, man, probably snake eyes.

That is the Exactly.

Okay.

The question should have been, what is your favorite GI Joe and why is it snake eyes?

And I will, so the movie is Top Gun, which has influenced many people and, and truthfully, I think there's something about the podcast one day we should come back to on the, there's something about pop culture that just influences people.

Like how many people have gone into the military that I've interviewed that it's 'cause of a book that read or a movie they saw.

We do a great job of that Right.

In America.

Um, but I, I have to say with GI Joe, like they came out with a movie in, I think it was oh five and oh six, Channing Tatum, who I went to middle school.

Oh, that's right.

I forgot about that.

Was the lead actor was Duke, wasn't he?

Yes.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Which killed me because we were literally both played football together.

He goes off to be a stripper.

I'm very successful and I love him.

I like, he is such a nice guy.

I am so glad.

But truly like this thing I grew up with, which I was like always gonna go into the military.

He is Duke.

And he gets to do it.

And the dude who gave me the, the CW four later Chief Warrant Officer or uh, CW five Thompson gave me my check ride in Germany is in that movie in an Apache.

And I saw him and I was like, oh my God, that has to be Thompson.

And I stayed around for the, uh, the credits and sure enough, it's this guy.

Like, how, how did this happen where Chan is the, the lead in this movie?

And I like grew up worshiping this, this toy Anyway.

Did it?

Yeah.

Did it almost like pop a bubble for you because, or was it I like know.

Gosh.

So are you, do you, are you still in contact with No, I'm not with Mr.

Tatum.

No, I'm not at this point not, but I would love to be.

Okay.

Uh, Mr.

Channing Tatum, if you're out there.

Yeah.

Uh, we would love to do a full circle interview with you on what Ryan was like in high school.

Audience wants to know.

Ryan does not want the audience to know.

So edit radio silence is okay.

Yeah.

That's fantastic.

Okay.

So now, uh, you know, humility aside, you've been just, you know, just crushing it.

Um, and then you, you graduate you, so do you guys have a wing ceremony and then a platform ceremony?

Is that different?

No, the, the ceremony's, even the, the ceremony of selecting the aircraft, I wouldn't even call it a ceremony, it's just, and I said that earlier, but it's like we sit down in a room, they put the things on the board, you pick and you leave.

How nervous were you?

Super nervous because you're like, this is the rest of my life, super nervous.

The same thing at the agency.

When you get your first assignment at the farm, it's like they hand you an envelope, you open it up, and this is gonna dictate literally the rest of your life.

Oh my gosh.

And, and you see people in the audience, you're like, oh, oh, shit.

Or like, yes, I got this thing.

It's weird being in those moments where, you know, like, this is a moment that will affect the rest of my life.

The trajectory, the rest of my life will be defined by what happens at this space.

It's, it's almost like these cinematic moments that you feel like you're like sitting in.

You're like, I, most of the time I was sweating bullets through all these things, like, they're gonna kick me out.

I'm failing through this thing.

Totally.

And then, you know, in your case.

I'm always interested to hear for the different branches and paths people have, like how do they do it in, you know, recon or being selected for a sniper or what ship you're gonna.

Command.

Yeah.

In, in the Navy, all these things.

Yeah.

I hope, you know, from my time in the service, what I've found is that there are a lot of points of meritocracy.

Like they're, and they're very clear and cut.

The Marine Corps does something a little different, um, to the way that we, and I don't know if this is true for the Army, but the way that the Marine Corps, when they're selecting officers, they do it on a, uh, on a, on a third's system.

Because what they don't want is they understand that.

I mean, any logistician out there will always understand that, you know, logistics wins wars, right?

That, that is, you know, Napoleon, right?

If you know in is March into Russia, right?

Like huge, huge blunders that have, and so what we try to do is we do what we call a quality spread.

And so we'll do, uh, the top, uh, top third, middle third and bottom third, and then they spread the MOS or the military occupational specialties.

So not.

Everybody gets to be infant.

You don't take your top third to go infantry if that's the thing.

And so they're able to take people across.

Now that does people then start to game the system like, okay, well I can't get number one 'cause get one number one's guaranteed where they want to go.

So then maybe I need to be 22.

Right.

You know?

And like, how do I get 22?

'cause that's the top of the second tier.

Yeah.

Oh my gosh.

Which still means infant.

So it does allow for a little bit of gamesmanship inside of it is the way the Marine Corps does it.

Yeah.

Um, or they say they do it.

Um, but you know how that happens inside.

Interesting.

Really up to them.

Uh, there, it still is a human business.

I would recommend anybody that's looking to join the service understands that it is a meritocracy in a lot of ways, but it is a human business.

Yep.

Very much so.

And so true.

Who you are, how you act.

Um.

The idea is that the instructors oftentimes, uh, are teaching their own profession, and they get the opportunity to select who they would want to serve with.

So, uh, maybe don't be a jerk.

True.

You know, through your, you know, maybe that again, like you could be number one, number two, and there's like, I'm not saying people weight things or put their finger on the scale, but if you're like a butthead through school and one of your cadre, you guys say cadre in the army.

Yeah.

Incorrectly by the way.

Uh, we say cadre.

Hmm.

Um, and, and marines.

And it is, uh, you know, they're picking who they have the potential to serve alongside.

That's so true.

And so if you're just like booger eater who's like, just mean to everybody, and you're like, he no thanks, he's smart, but he's toxic.

They, they can, they can affect that a lot.

I've seen that.

You know, so true.

Just a quick word for myself before we dive back into this combat story.

Many of you know, are previous interviews with AJ Chui, marine sniper recon operator, and the man who tracked, hunted and ultimately eliminated Iraq's Deadliest Sniper Juba.

This was an enemy responsible for deaths of over a hundred Americans, some say, up to 140, many of which were filmed and posted online.

Aj, who was just a very humble, very young Marine at the time, took that fateful shot, put an end to so much pain for so many families.

We never took credit for it.

And over the years that story's changed and been retold countless times.

I'm incredibly proud to let you know that you can get your hands on AJ's new book, dark Horse.

Harnessing Hidden Potential in War In Life.

A book I asked him to write after I interviewed him immediately after I interviewed him.

It's part memoir, part roadmap, a look at the lessons AJ learned through combat and throughout his career and how they can help all of us find strength and purpose.

If you enjoy Combat Story, you're going to love this book to get a copy, head to combat story.com/darkhorse.

That's combat story.com/darkhorse.

It's packed with details and insights that we never got to cover in our interviews, and I know you're going to love it.

Now, back to this combat story.

Okay, so first unit that you went to after.

So all said and done.

Uh, what was the first unit?

Where was it at and what was that first day?

So what is the uniform called that you guys, when you check into your unit, uh, board shorts and flip flops, is that what pilots do?

Or is that the army?

Because I know the Marines, we show up in service Alphas.

Yeah.

Okay.

Um, truth be told, I don't think we had a name for the uniform that we wore, so that totally makes sense.

So I, I showed up at a unit in Germany that had just redeployed like a week or two before I got there.

Very, so by redeployed you mean got back, just come back from Iraq.

So this was early, like probably February, March of oh four, and it was a cab unit, which was very cool.

Which folks?

AJ called the Cav Stetson.

A cowboy hat.

It's called a cowboy hat.

That's what I, so, uh, I'm from California, man.

A cowboy hat.

Please let him know in the comments how you feel about that.

If you're calve, um, one of those little tassels you guys have for That's, that's right, that's right.

And spurs.

Uh, so, but I really wanted to go to a cab unit 'cause pre nine 11, like they're, you know, you didn't go to war.

Going to a cab unit was pretty cool.

Okay.

Like there's a lot of tradition there.

Um, it's fun.

They do this thing called a spur ride where you earn your spurs if you're not in combat.

That's how you get your spurs.

If you go to combat, that's how you get your spurs.

But in an army where that didn't go to combat, are we talking like physical spurs?

Yeah.

So like, you'd wear 'em on your boots.

No way.

Special occasions.

No way.

And your Stetson.

So I would be way too irresponsible with that.

Oh my gosh.

So I mean, that, that is a ceremony and it is fun and it gets crazy and you're drinking beer outta your Stetson to help form it.

And it's a lot of fun.

And I got to go through that in Germany and that was a great experience.

With the exception, it was three years in the same unit and I did not deploy.

So the unit I was at had a really bad battle in Iraq on March 23rd, 2003.

So it was supposed to be this big moment for the long bow Apache.

It was a battalion, um, ex raid, basically a battalion uh, operation.

How many aircraft in the battalion?

So 24 aircraft.

Okay.

So all taking off at the same time.

That's a big logistic lift.

Logistically hard to do.

The maintenance hours not really done before.

Yeah.

They were gonna go and fly and stop somewhere, you know, shoot all these missiles at the same time.

Intel wasn't right.

A couple guys, uh, uh, crashed on takeoff, some brownouts, a lot of things they weren't used to training in the US or Germany.

Oh.

And they ended up hovering over enemy positions, getting shot to hell.

Came back one of, yeah, just terrible opening round for the, for the long bow.

Yeah.

Three days into the invasion.

Super early.

So they stayed there throughout the deployment, but that hung over their head.

So I remember like March 23rd, 2005, that anniversary was a very somber day.

So that unit did not redeploy.

It had to like get refit.

So they were like benched basically.

Yeah.

Um, so morale wasn't super low because of that and people rotated in and out.

But certainly that unit, it was six.

Six.

Cav had this reputation now.

Yeah.

It had a stigma, right?

Yeah.

Um, our sister unit, there were only two units at our very small base in Germany.

Six.

Six CV and two six Cav, both Apache battalions or squadrons.

The two six Calv then went to Afghanistan and I desperately wanted to go with them desperately did not go.

And so I spent three years in Germany, had a blast, got married, like, you know, my wife, Val, who you know, came over, traveled a ton, made great friends.

But all this time, but certainly like 2004 to 2007, we were busy.

I am sitting here watching you guys, like you've gone into Iraq, Fallujah happens, right?

Um, and then the Army's in Ramadi at that timeframe, right?

Yeah, it's killing me.

W Pat Fagan who introduced us to Will, uh, who we interviewed, Pat's gone down range two times by then.

He's in Germany with me, and so he's in the army that deploys.

I'm in the army that sits.

So did, did you feel that you suffered from that, this idea of imposter syndrome before you went to, 'cause like you're probably at young and you're like, I'm ready to go.

Did this, does this one imposter syndrome started to set in?

Do you think you're seeing a lot of people constantly go back and forth and you're like, man, I'm sitting here on the sidelines ready to go, put me in coach.

Is that Yeah.

Is that a form?

I'm not trying to put No, no, no.

I, I don't think it is.

I, I see where I completely see that.

I don't think so.

I think probably that first unit being there with everybody else has a combat patch.

They've been fighting for a year.

I have nothing.

I'm the new lieutenant already a bad moniker.

You know, like you're brand new lieutenant un untested.

I think that taught me a lot of humility and just.

Learning from these guys who are super experienced, these warrant officers as you know well, um, who have been flying literally for 20 years.

I'm like 23, 24.

Um, they've been flying almost as long as I'm alive.

They technically, I outrank them, but like, let me, you're never gonna pull that.

I'm never gonna pull that.

And, and I, I wouldn't have, maybe that was part of my dad teaching me that.

Sure.

I think I, I appreciated.

Just learning what I can, that imposter syndrome came probably after I got out of the military.

Okay.

And I just felt terrible because of it.

Okay.

Okay.

So now, now 2006, you're at six.

Six.

Cav.

Six.

Six Cav.

And that's in Germany.

Yep.

And so when do you, when do you first deploy to Afghanistan?

Yeah.

Is that, so I go to that Army court, the infantry course.

NC.

Yep.

So we go through there and then, and importantly, we have our first kid at the time.

Yeah.

And then Owen, who's in the other room, I happen to like him.

Yes.

Um, we have him.

And then I, and I, I think that's important 'cause I, I don't know what it's like to deploy without a kid, but having talked to vets, it's a big difference.

Mm-hmm.

It's a very different story when, when there's nobody else waiting for you.

On the way back, I, I had members of my team who, um, were in Iraq and when they had a child, their child was born while they were gone.

And there was a marked difference, like very much different, like, not necessarily risk averse, but they had a lot more to live for.

Yeah.

Um, and it was, it was a conversation and a constant decision these young men had to make when they had someone that wasn't just a partner or a spouse.

It was now another living being that they had brought into this world.

It really changed their perspective.

And something I couldn't empathize with, you know, I could empathize so much, but I remembered, I remember witnessing that and seeing that.

And so, uh, I can only imagine like as you're getting ready to go, now you have this Yeah.

This whole other life and this whole other family and it, the, the, the price of a mistake I think not only has the potential loss of life when it comes to the soldiers that you're supporting, but also if you, if you make a mistake in a brown, like I'm sure it put a lot, a lot of weight on that.

Totally.

Yeah.

And, and so, you know, he's very young.

And then I go from there to the hundred first, which was a big deal.

Like that's a very, um, kind of iconic unit.

Mm-hmm.

In the army.

The 82nd, the hundred first, lots of trash talk.

It's not special ops, but look, that is a, a feeding ground for some of the special ops pipelines and.

I was incredibly proud to go to that unit.

You know, I had read and studied Band of Brothers, Normandy, like these guys with the screaming Eagle patch.

So I loved going there.

They had been downrange so many times.

Oh yeah.

They like lived there.

I mean they were in the very first battles in to Bora Anaconda, like these 10th Mountain was there with all the, anyway, so guys I had read about are now in my unit, literally like by name in Oh.

Um, not a good Day to Die.

Yeah.

And we deployed just a few months after we got there.

So we go to Afghanistan in like, just before I should know the answer to this, maybe the day or two after Christmas, 2007.

And then I'm deployed basically for all of 2008.

And that is my year in combat.

Why the Army deployments?

I, I mean, I totally understand why you guys, why you guys do that, but it's generally 13 months right?

Is kind of what It's 12.

Yeah.

Okay.

Usually for us, uh, ours were six, six and sometimes seven.

Uh, I had a couple of longer ones based off of just, you know, being their first and leaving last, but the fatigue that Marines felt at month five.

And then we, we felt for the army, we felt for the soldiers because we would be hitting at month five.

Things start to change, right?

You have now been there a whole bunch.

You've, you know, you've learned and understood people and we're like, we're smelling the barn.

We're looking at like, Hey, we're outta here.

And we're looking at dudes and hanging out with guys or gals that are like, well midway.

Yeah.

Just hit the halfway point.

Yeah.

And it was, um, I was actually appreciative of the Marine Corps and their deployment models.

Um, because of that, I think that in the type of environment I, you know, and I'm not calling any kind of major, you know, service out, but I think that in the environments that we were at.

It weighed so heavily on us because we were, we were cops and cops that were getting attacked left and right and couldn't fight back.

And you could only handle that so much before you kind of go numb to it.

And that's where we felt it was dangerous.

And I remember a lot of the Marines, um, now we were a totally different branch of service that deploys for a totally different reason.

We are not doctrinally supposed to be, you know, uh, you know, owning territory, right?

We're supposed to go in and shock troop our way and then turn over stuff to the army.

But boy, I felt for you guys, uh, for 13 months.

Did you have any break in the 13 months?

Yeah, I had an r and r that was a little bit early so that I could take command while I was there.

Oh, cool.

Which was good.

Um, was the RR beneficial or was it, 'cause we've always, like, again, I've never experienced that, so we only Oh yeah.

That's interesting because then you, like, you, you're like, you're in the fight, you go back for a week or two or whatever it is.

Yeah.

Like 10 days you play dad for a little bit.

Yeah.

And then you're right back into this thing.

Yeah.

It, I, I don't know.

I, I would think it was helpful, but for me, like I really wanted to be in command 'cause I was in a staff job, which any like officer hates.

Mm-hmm.

Like you'd rather be in a line company.

Um.

But I, I kind of secured that line company role.

And then they knowingly were like, all right, take your RR now so it doesn't, and there's also a clean break.

Yeah.

Right.

It was really good actually for that.

Um, and to your point on the deployments, like when I was at that school at Benning, the M Triple C mm-hmm.

Lots of those guys were on the front edge of the surge.

And so like, we had a couple of Stryker guys who were this infamous unit that literally came back from a 12 month, got off the plane, and Rumsfeld was like, get back on.

And they didn't get to see their families.

They put 'em on the plane and sent 'em back for four more months.

Oh no.

And they would talk to me about the, and these are all officers who were platoon leaders, and some of 'em were going to Ranger regiment and some were going sf and others were just going back into big infantry.

Um, but truly like the, the necessity to be there for guys who are going through the, dude, we were going home at 12 months and now we're going back for four more.

Same place.

And you know how it feels when you're redeploying.

You're like, all right, I can let this weight drop.

Yeah.

And, and then have to put that armor back on.

Yeah.

So, so visceral the way they talked about it, it was, again, very helpful for me to hear.

What was the, what was the, the reasoning behind the surge?

It was the surge.

It was like.

We, we need all you guys there still.

I mean, I'm not the brightest guy in the world, but I feel like the Army's pretty big.

Like I I I'm sure these are questions that a lot of Yeah, no, I know.

You know, your guys and gals asked through that, but man, that would, it's interesting.

Morale killer I could have.

And then how do you as the commander Right, as a, you know, in the unit that got redeployed Right.

You know, dealing with that, like they're pulling the, the, the little rug out from underneath these guys.

Totally.

Right.

Yeah.

You know, that now have to like, go back.

That would be very hard to manage.

Um, I think on a human scale so hard.

So yeah, I come back from r and r and, and it's, it, it, as you know, 'cause you've been in Afghanistan, it's probably April of, of the year, so like the cold months have gone.

Mm-hmm.

The fighting season kind of starts.

Mm-hmm.

A couple guys had gotten into fights.

One of our sister battalion, so I'm in coast in Eastern Afghanistan mm-hmm.

At Fab Salerno.

And one of our units that's up in, um, Jalalabad, which was known for just being a little more kinetic, had already had a fight.

The, the company commander there is this guy that I really, really liked Joe Brule and almost want to hate him 'cause he was so good at his job.

Um, he, he did.

So his, his, uh.

A company gets into this nasty fight.

It's the first one of our deployment.

He writes this really nice, a a r sends it to all the company commanders and battalion commanders.

He's like the golden boy's.

What?

He is totally golden boy.

I, and we would give each other Yeah.

Shit later on.

And, and I, I love that guy, but I remember reading that like, ah, he got into it.

I didn't, and I took over from a guy who is truly a legend in the aviation community.

His name's Clint Cody.

His dad was the highest ranking, um, general in aviation.

Oh, wow.

So he was vice chief of Staff of the Army at the time when Clint and I were serving together.

So literally everybody knows the Cody, the Cody clan.

General Cody came in and did the change of command ceremony for us.

Like everybody loved Clint and I was taking over, I was this guy who'd never been in combat.

Clint was in Torah, Bora, like imposter syndrome through the roof, which is another reason some of these guys, um, who I serve with for that year, you know, later a couple of them have reached out and they're like, Hey, I heard combat story and I wanted to tell you, you and Clint were the two best company commanders I ever had.

That's fantastic.

And just to be mentioned in the same vein, uh, meant a lot to me, obviously, but it was, it was tough coming in.

I'd much rather take over from a moron.

Yeah, totally.

It just ran something into the ground.

Totally.

Yeah.

But that wasn't the case.

I took over from a great guy who, who's still in, he's a brigade commander.

What was your first conversation?

So I'm not gonna ask you who the most important people inside of a aviation squadron are.

We all know they're the maintainers, but the, um, you know, with your conversation with the people that you were leading when you had, you know, literally a giant, I have a friend of mine who took, did the same thing.

We have a guy Brian Osh, who's like a legend.

We had a friend, now a friend of mine who took over as a company commander in Fallujah from a legend.

And I remember his first conversation with us, um, and how he kind of went through that.

How was that?

When did you address the entire company?

Did you go section by section?

Um, how did you try to instill confidence in these young men and women that were forward?

That you're not going to fail.

Yeah.

That you're going to carry on this legacy with them.

Gosh.

And they can trust you.

So embarrassing.

So, uh, so embarrassing.

I already have all this imposter syndrome.

Um, rightly so.

And Clint is a great guy.

He and I got on very well and he did so much to set me up for success.

Um, we're doing the, the handover and first thing you have to do is a change of command inventory, which is a pain in the butt.

You gotta inventory all the serial numbers on every piece of gear, including helicopters.

Yeah, yeah.

And all the eight, I don't know how those go missing, but Sure.

It's terrible.

But like little boxes on the aircraft.

Um, so Doug Dein is my first sergeant, tough maintainer, older guy, has a couple kids.

He has been down range a few times, like a few too many times, right?

And so, yeah, I know the type, so I'm like, Hey, top, we gotta, we gotta inventory everything.

And he's like, we're not doing the aircraft.

And I was like, Nope.

Pull everything off.

We're gonna inventory.

He's like, we're in combat.

We're not doing that.

And this is behind closed doors.

And I'm like, no, we're gonna do it.

And we have this fight and we start.

And this is just what I should not have done.

So we, I, I can't remember how far we got into it, but eventually I saw the error of my ways and, and I came back to him and I was like, all right, we're not doing that.

And, and I, but I did say, Hey, you and I, we have to be on the same page.

Sure.

And I'm gonna make sure that we are.

And we had it out.

And it, there was a little bit both ways in that, going both ways.

Um, and he and I are friends to this day.

Like he was such a great partner for me.

And it just took a, no kidding, like sit down.

Hey, I screwed this up as the junior commander guy.

He, I can't, it was probably in public.

We had this discussion that shouldn't have happened in public and we both just said like, we're here to support each other and this is it.

And that's what I should have said before I did anything was had this discussion with him in private Sure.

And just really said like, we are gonna live and die together.

And we did.

And it worked completely well after that.

Um, but I wish I, and I think the, the crux of this was we had this disagreement in public.

Yeah, totally.

And that was the thing that should not have happened for both of us.

It's hard 'cause egos flare.

Right?

Totally.

You know, you're in charge and I'm, and I'm worried like this is what I've been told I have to do as a good officer, I do this.

Yeah, totally.

And I needed to be more flexible.

And Clint had deployed multiple times and he's like, this is the fourth time you don't need to do this, man.

Okay.

So I actually have listen to them a follow up on that.

That is, 'cause now we're in this, it's kind of a, uh, an old trope that happens is you have the young officer totally with the seasoned enlisted and both have their way of doing things and both of them are the right way of doing things.

Yes.

If you ask, you're right.

What advice would you give to young officers, uh, in this space?

'cause I had never been an officer in this space.

So what advice would you give when a senior enlisted says, Hey, this is how we do things in this unit.

And, and almost it, it almost seems like both are almost kind of, vying for control is an interesting kind of dynamic.

Yeah.

'cause there's a human element.

What would you say would be a a, a good piece of advice for a young lieutenant who is taking over a, uh, a platoon?

I don't know your guys' like specifically Yep.

Platoon.

Yep.

Uh, in the aviation, we have infantry platoon commanders that run headlong right into their senior enlisted because they're fresh out.

So there's like very much like an institutional way of doing things.

Yeah.

And then there's like, the way things are kind of done.

How would you suggest people navigate that in the future?

So I think I did it correctly as a platoon leader, which makes this even more embarrassing when I screwed it up later, like I had the right answer and I was like, we're gonna go a different direction.

Because in Garrison it was like how everything was taught pre nine 11.

And I think in combat I just needed to be more flexible.

And I did, I took some risks before taking command that probably were ill-advised, but helpful for, for my career progression.

This is one where screwing that up, screwing up a change of command inventory only hurts me really as the commander.

Okay.

Like I signed for everything.

It's my name on the line.

Sure.

Some of it's delegated, but truly in the end, if something's missing, it's on me.

So if we screw that up, that's on me and I should have allowed flexibility there.

If it's ethical and you know, somebody's a is on the line and it's someone else, I'd probably draw a harder line.

But where I can fall back and, hey, if something goes wrong, it's my butt on the line and not one of the soldiers Probably give a little more flexibility and listen to the seasoned guy.

That's interesting.

But if it's ethical and, and like we have a disagreement and we wanna look the other way.

No.

Like I, I think you still gotta hold the line right on that.

That's a tough one.

It, I, I can, I can definitely see many instances in my own career where we.

I do not envy young officers taking over seasoned platoons.

No, that is not a, um, we can do a better job as a military preparing these young officers for those initial conversations and what, um, how to navigate those things.

I, I think, and we'll let people do it out in the comments if they have an idea of what the right one is, because it's very tough for the, I would get asked that as a, you know, my previous rank and title, that was one of the things I had a lot of lieutenants come to me and say, gunner, I have X platoon sergeant.

I don't know how to get through this.

And sometimes it was me having to force both of them saying, both you two, sit down in this room and figure it out.

Yep.

Because the longer that you guys, mommy hates daddy.

Oh, it's mom and dad.

Dude.

It is.

And, and the longer that you fight, the kids see it and kids will see it.

Not now.

I'm not, you know, saying any of the young enlisted or, you know, staff and CEOs or kids, but we're using the metaphor.

Even the officers, the platoon leaders are gonna see it.

They're all watching you.

They're all watching.

They're all watching you and how you're gonna get along, especially when you're taking over from like a legend.

Yep.

Right.

Yeah.

Yeah.

Did you talk to him and be like, Hey, what do I do in this?

Or was he gone by that point?

Um, he had taken off pretty quickly, not he was going to like one 60th selection, so he is just like, couldn't have done any better.

Yeah, right.

You know, and they're like pulling him into this unit and, but he was, he was very helpful and he, he even said to me, Ryan, you don't need to do this.

But, but at the same time I was thinking, well, it's easy for you to say your dad's like vice chief of staff of the Army.

You have a little bit more top cover than I do.

But that's not fair to say either.

He didn't have to do it for that reason.

Um, and it was truly just like, this is how you do it.

Do it this way.

Don't screw up.

And I should have just been more flexible.

Interesting.

Yeah.

I've heard the trope before, you know that no matter what, always listen to your senior enlisted.

Right.

And I think, and I think that's good, but I also have been the senior enlisted who likes to do things that are less than doctrine or less than what, like that would potentially put you Right.

Or the commander at a potential disadvantage.

Totally.

Yep.

Interesting.

And so it's, I I, I love the idea that you're talking about who would really suffer if this thing screwed up.

Yeah.

You know, would, was there going to be a potential loss of limb life or eyesight?

No.

It's maybe I get reprimanded and I was already, and this can probably transition us, I was already thinking of getting outta the army.

Interesting.

So I, I really wanted to command in combat, but I didn't see myself long term in it.

Sure.

Yeah.

I think a lot of guys that I've seen is their favorite position as an officer has always been like a company commander.

Yeah.

That after that it gets kind of political and sometimes people get yada yadas.

Right.

Um, and I can see that.

And so when you're like, you've reached that and you're like, I'm good.

So, okay.

So you were there for 12 months?

Yeah.

Um, you had six months as a commander.

Uh, a company commander, probably eight months in country as a company commander.

Okay.

Okay.

So eight months in country and, and, and primarily you said outta coast?

Yep.

Okay.

What I understand is that the Army uses their Apaches, like Calvary, they employ them as almost an attacking unit where we in the Marine Corps oftentimes place our aviation as a supporting unit.

Or you, I'm sorry, a maneuver unit.

You guys might be your own maneuver unit.

Mm-hmm.

How did that work when you were working and you were underneath the hundred and first at the time?

Yep.

I was in the hundred and first we were in a task force element, which just meant that.

Like traditionally there'd be three Apache companies in one location, but they split us out.

So we had Chinooks, Blackhawks, Apaches, and Kyles all in one unit.

So Lyft, reconnaissance, gunships, all of that.

Okay.

Yep.

So just for flexibility in the battle space, which was a good idea.

And my battalion commander there was the Apache Battalion commander, whereas in other locations you had the lift guy or the recon guy.

Um, there were really two types of missions we had.

We were always on QRF, we always had a QRF ready to respond if somebody was in a fight.

Um, so we'd have two aircraft always ready to go.

And earlier we were saying like 24 aircraft online in Iraq.

Um, that never happened.

We almost never had more than four Apaches at once.

So typically it's going out in a pair of two aircraft.

Wow.

So very different than what these guys started the war with.

So we'd have QRF ready to go and we'd probably.

If you didn't get called because we have duty day as, as you all know, certain time where we can fly and then we can't fly anymore for crew rest.

So I'm gonna call, I'm gonna dig in on crew rest for a minute.

Let me tell you.

If we got too far into our QRF window and we knew we were approaching crew rest, we'd launch and just go and, and touch base with different units on the ground.

Like, do you want us to go look at something beyond your line of sight?

Can we go help you out?

Do you need us to do anything for you?

So we'd launch almost every day when we were on QRF if we didn't get called.

And then the rest of the time we were doing what we'd call deliberate operations.

Sometimes it would be an escort for a lift aircraft, dropping off equipment here or there.

And then other times it would be like we'd have a an ODA unit co-located with us.

So we'd go and do deliberate ops where they'd go and, and hit a house.

There was no like little birds for one 60th, couldn't operate at this altitude.

That's generally, that's an interesting question I have about al.

So in coast it's interesting.