Episode Transcript

The public has had a long held fascination with detectives.

Detective see aside of life.

The average person is never exposed her I spent thirty four years as a cop.

For twenty five of those years I was catching killers.

That's what I did for a living.

I was a homicide detective.

I'm no longer just interviewing bad guys.

Instead, I'm taking the public into the world in which I operated.

The guests I talk to each week have amazing stories from all sides of the law.

The interviews are raw and honest, just like the people I talk to.

Some of the content and language might be confronting.

That's because no one who comes into contact with crime is left unchanged.

Join me now as I take you into this world.

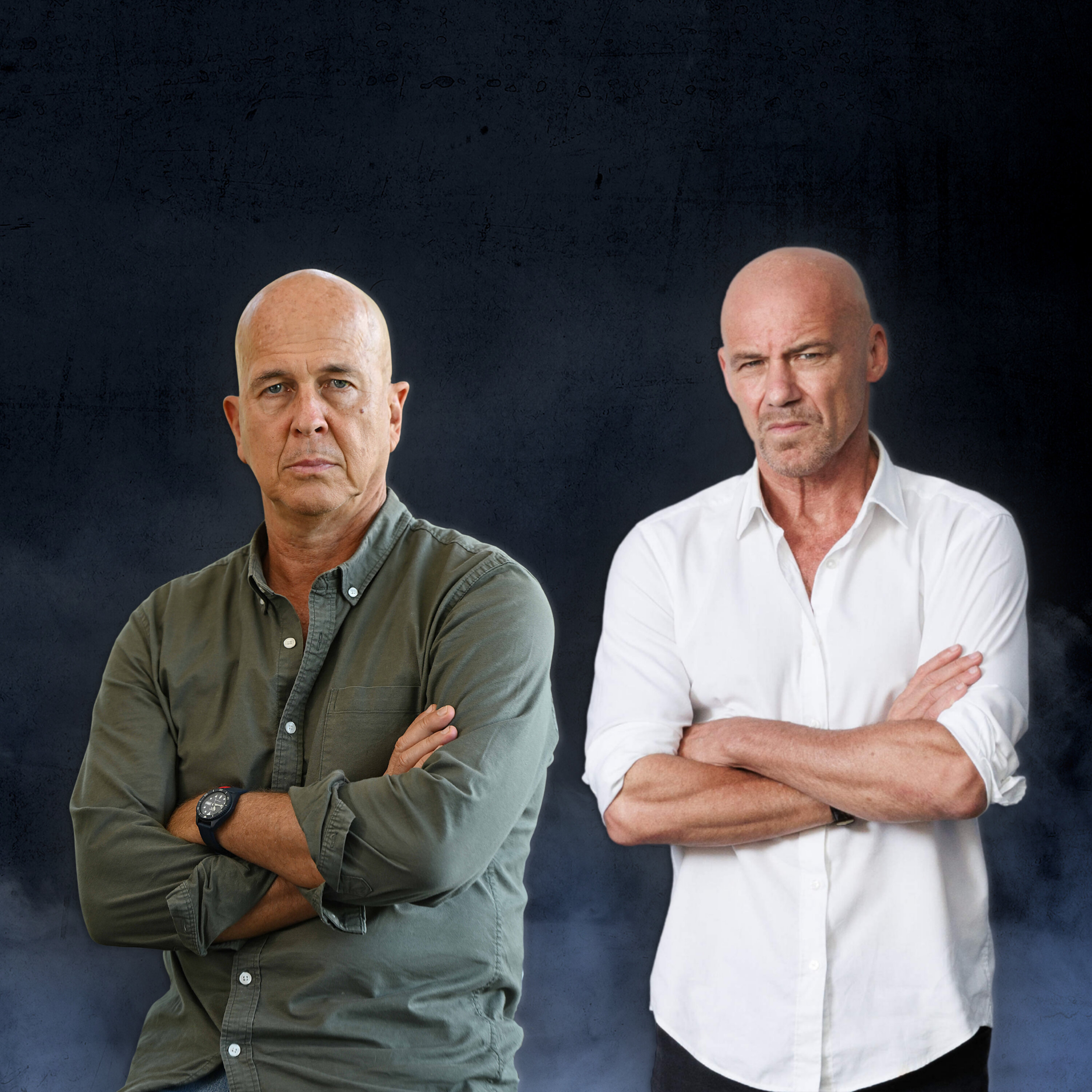

Today, I had the pleasure of speaking to award winning foreign correspondent Peter Grest, who was wrongfully imprisoned in an Egyptian jail.

He spent four hundred days locked up in the Cairo prison, whereas forced to survive conditions after he's falsely accused of being a terrorist.

We talked about his lengthy time behind bars and how that experience made him reflect on his own life and discover a strength and resilience he didn't realize he had.

Peter also spoke about his life on the road, working as a journalist for the BBC, Reuters and Al Jazeera in some of the world's most dangerous locations.

In these environments where colleagues have been kidnapped and murdered just for simply doing their jobs, Peter also spoke about the importance of freedom of the press and the crucial role at plays in world events, a subject he is very passionate about.

Here is his story, Peter Gresser, Welcome to our catch Killers.

Speaker 2Thanks for having me.

Speaker 1Well, I've got to say, Peter, I've learned a bit about you.

I knew a bit about you before you were coming on as a guest.

And I've got to say a career as a foreign correspondent that's about as good a job as you can get.

I think.

What's your take on it?

Speaker 2Yeah, I loved it.

I mean the thing that drew me into the career was a couple of things.

It was a license to indulge your curiosity.

You know, if there was something that you're interested in, then it meant that you were someone was prepared to pay you to go and investigate, to stick your nose into someone else's business to find out.

But it was also I guess, a license to have adventures to some extent.

You've got to be careful what you wish for.

I guess.

Speaker 1Yeah, Well, I suppose for all the good parts there was well, the experience you had in Cairo and Egypt.

Obviously you don't put that as a high point.

But it's a fascinating job because you get to go to some of the world's hot spots where everyone's curious about it, and you were actually there reporting on the ground.

Speaker 2Yeah, and not just I mean the hot spots are the obvious ones.

They're the ones that tend to make the headlines.

But places like Antarctica, or places like you know, corners of Africa where they're translocating offence, or parts of the Middle East where the extraordinary archaeological excavations that are taken place.

I mean, all of this stuff is open to you as a foreign correspondent.

So as long as as I said, as long as you can make a case for a good story, then you're able to go and stick your nose in.

Speaker 1I think it gives you a worldly view, doesn't It's like we've come back to Australia, but it gives you a more worldly view.

Speaker 2Yeah, you can't help but not have an understanding of the globe as a as a fascinating, extraordinary place.

I miss it terribly, I really do.

It became a part of my identity and not being able to do that, I think is something that was quite tough for me.

But yeah, it's still very much a part of my DNA.

Speaker 1Okay, And you're also a member of a very limited club of people that have been arrested in foreign grounds for a variety of fenss terrorism.

For your one, we've dealt with Kylie Moore Gilbert and also Sean Turnbell and yeah, even chain Lay.

Speaker 2Yeah.

In fact, we're all together as a part of the Awada group of people who are Australians who have formerly detained arbitrarily.

And Kylie, Sean and myself are all coincidentally academics at mcquarie University where we've decided to form our own little nest of spies and terrorists.

Speaker 1We've had all those guests, all the people we just mentioned on the podcast here, and I've been amazed by this story, but the amazed how they also came through the experience, but one exclusive club you're a member of.

Speaker 2Yeah, it is a pretty special club.

And I love them all.

You know, they're all extraordinary people, and I guess in a way there's a sort of self selecting group in that they've come out of it, out of their experiences with the determination and strength to do something with the time that they spent behind bars hasn't killed them.

It has made them stronger and it's given us all, I think is a kind of common language to talk about the experience.

The trouble is, you know, when you go through that kind of a kind of time, when you're imprisoned like that, the language that you use really isn't understood by people who don't who haven't experienced it themselves.

It means that we can talk about time behind bars and understand each other in a way that is very very rare, and that's that's quite special.

It gives us a special bond.

Speaker 1I would imagine it would help in that regards, and then be a fascinating discussion around the dinner table when you lot got together too, I would imagine.

But how ironic you've all ended up at Macquarie University.

Speaker 2Yeah, yeah, Well, like I said, maybe there's something special about Macquarie.

Nobody tell Asier.

Speaker 1Though now your time that we're going to obviously break it down what happened to you over in Egypt, But I just want to upfront, like I know through your experiences.

I've read your book and really enjoyed it, and it was very open book about the experiences you're going through, not just physically but emotionally and every psychologically, everything that happens to you in the prison and having you freedom taken away.

What was the lowest point as you spent four hundred days there, but was there a low point that stands out?

Speaker 2Yeah?

I think the day we were convicted.

You know, up to that point, we'd always believed that the case would go away.

When I was arrested, I was convinced that someone had screwed up, someone had made a mistake.

Maybe they'd misread the arrest warrant for Peter Greystone rather than Peter grest Or, they'd misinterpreted something that we'd written or published, and that with a bit of explanation, maybe a few phone calls, the thing would go away.

It didn't.

We thought when the investigators started looking at the prosecutor started looking into the case that they'd realized there was no substance to any of the allegations and drop the whole thing.

We thought much of the same when we started the trial.

We thought the judges would chuck it out the end of the trial.

We thought that it was so obvious there was no evidence to convict us, that the whole thing would would have have to be acquitted and that free.

At the very worst, they might have convicted us of some kind of administratives of fans and sentences to six months.

We'd already done that time at that time and release it's on time served.

But to then be convicted and sentenced to seven years, that was a very very tough day.

Speaker 1I suppose that's when it became real and that's the light that you were hoping or where justice would would come.

It must also impact on you greatly that you're in there knowing that you haven't done anything wrong.

So it's not just I think there's two ways you could do prison, aka, well I've made a mistake and I'm paying my dues.

But if you're in there and you know you haven't done anything wrong, that sense of injustice must either way.

Speaker 2Well, yeah, but there is a third way, and that's to use the time that you have behind bars as a way of fighting for the greater issue, the greater injustice.

I mean I didn't.

I realized after we were convicted that it had nothing to do with anything we've done, but everything to do with what we'd come to represent, and that was press freedom, okay, And so in framing our case as an attack on press freedom, we come to fight for that principle rather than for our own our own selves, and I think that made it much more survivable because it gave what we were doing, what we were going through a sense of purpose and meaning that it wouldn't otherwise never have had.

Speaker 1Okay, that makes sense, makes sense.

Well, look we're going to take you, take you back there.

I apologize for that, but before we do, let's find out a little bit about who you are, and so what what's your story?

Where'd you grow up in your childhood?

Speaker 2Childhood in Sydney, out the northern suburbs in Waronga, kicking around the bushlands of Lancove River National Park.

Speaker 1Those bush lands very well.

I grew up in Epping though that spent half my childhood roaming the bush around there.

I probably threw rocks at.

Speaker 2Yes, probably did.

We probably chased the same snakes as well through the bush at various points.

So I had my childhood in Sydney, you know, pretty idyllic really, as a lot of kids do if you're living growing up in that kind of environment.

We moved to Brisbane when I was about twelve thirteen, so I had primary school here in Sydney and then high school in the university in Brisbane.

Yeah, very easy going childhood, really camping and falling around, going surfing and enjoying the beach.

The countryside has a lot of a lot of kids do.

Speaker 1Okay, what was what drew you to journalism?

Speaker 2I guess it was funny because it was more the thing that didn't turn me off than anything that particularly drew me to journalism.

I remember at the end of high school I had to I knew I wanted to study something.

I didn't want to go on to the workforce at that point, but I had no idea what on earth I wanted to study.

And there was I remember midnight before the university application form was due.

It was completely blank.

I had no idea what I was going to stick on there, and there was a book with all of the courses that you could do in the state was called the q TAC Book and the queenslan Tertiary Admission Center Book.

And I remember thinking, if I don't know what I do want to do, let me get rid of everything I don't and see if I can narrow the field.

And I started crossing style.

I got rid of accounting, No architecture nowhere that was my dad's thing, medicine, law, no engineering.

I just kept crossing and crossing and crossing until the only thing that I didn't cross off was journalism.

And I figured that's that's it.

Then that must be the thing to do.

Speaker 1Follow follow that path.

Speaker 2Yeah, And so I went overseas.

I applied and deferred and went overseas as an exchange students South Africa for a year.

And while I was away that time in South Africa, during really what was the height of the apartheid years, it really settled in my mind that this is what I wanted to do, that was the right thing for me, because I think that time in South Africa really gave me a sense of social justice or injustice as I saw it.

Then, So what.

Speaker 1Period of time was that?

Speaker 2So that was when I was about seventeen.

Speaker 1Okay, so you would have seen the injustice.

Speaker 2And yeah, yeah, exactly.

This was during the This was before the end of apartheid in nineteen ninety four, when Nelson Mandela finally won the first post election of post apartheid elections.

It was in the early nineteen nineteen eighties rather so, very much a lot of injustice, a lot of social turmoil the time, fascinating but also very difficult.

Speaker 1Do you think that the experience sort of broadened your view on life?

Speaker 2And I think so.

I lived with Africanas who were wonderful people, and I could see and understand who they were and where they came from and why they felt the way that they did.

It gave me a degree of empathy and understanding that they weren't necessarily villains, but they were also exploiting a system that they benefited from hugely and it was fundamentally racist.

And so it gave me a sense of empathy and understanding that everyone has a perspective, everyone has a point of view, but also a sense of social justice that I wanted to follow through.

Speaker 1So one thing to tick the box and say, I want to be a journalist and study for it where did you get your first start?

Speaker 2And I got my first start at GMV six in Sheperdon, in my rural TV station down in northeast.

Speaker 1Victoria, reporting on cattle sales or yeah.

Speaker 2Reporting on dairy milk prices and on droughts and on farming issues, and local flower shows and school sports competitions, all of those sorts of good things.

I guess in a way, it was the place.

And I often tell my students there that I learned the skills to be a foreign correspondent in that job in Shepperdent.

Speaker 1Okay, that's interesting that it explained, well.

Speaker 2You had to work very very quickly.

You had to work across a very large geographical footprint.

You had to cover.

You had to figure out how to make really obscure, odd little stories accessible and interesting to a much wider audience.

You had to be accurate.

You had because I remember, I mean, all journalists have to be accurate, of course, But the thing about Shepherd was that in most newsrooms, and most capital city newsrooms, you're fairly disconnected from the audience.

Speaker 1It's not going to bump into the person you're You're.

Speaker 2Not going to bump into the person you're reporting on it, and you could guarantee in Shepherd and if you've made some cock up, sooner or later someone would tap you on the shoulder and as you're walking down the street and say, mate, you know you've mispronounced Uncle Joe's name.

You got that, You got the age.

Speaker 1I can see where you be coming from.

Its sharpening up your sharpening up your skills.

Speaker 2Sharpening up the skills, teaching you to work independently.

You work, you know, you're producing a lot of stories across a large area.

So yeah, I think a lot of the basic craft skills I learned out there.

Speaker 1Okay, now I'm sure BBC didn't pluck you from from there?

How did you?

How did you make your move to me working overseas and working as a foreign corres sliment?

Speaker 2From there, I went to Darwin.

I was in Darwin for a year, again getting a little bit of a taste for the adventure.

Speaker 1Well that would to foreign correspondent.

Speaker 2And then I got a job in adelaide in covering the basically for the ten network, and I was there for about three years, and I remember towards the end of those three years, I started to feel as though I was repeating stories time and again.

I've been able to pick up a script that done from twelve months earlier, changed the names and the dates pretty much and refile it because not much seemed to change.

I didn't feel challenged, I didn't feel I felt it was sort of rinse.

I was doing, covering stories on repeat, and I read and two things happened.

The first was that I read a book called One Crowded Hour, which is an extraordinary biogra of a guy called Neil Davis, an incredible Australian cameraman who covered the Southeast Asia during the late sixties and seventies an eighties.

He was in Vietnam, he was wounded, He saw more combat than almost any soldiers active soldiers.

He was wounded something like twenty three times.

And what I saw was an extraordinary professional who was deeply dedicated to his craft but was also experiencing was in the middle of really pivotal moments in history, and also having some incredible adventures.

And I thought, well, that's actually that's what I'd love to do.

Soon after the ten network went into receivership.

This was in nineteen ninety one, and to save money, they closed down the London Bureau, and I thought, well, this is ridiculous.

He can't have one of the main Australian networks without what's going without having a London correspondent.

So I marched into my bosses office and said, listen, if I quit and take myself to London, would you use me as a stringer?

And he said sure, why not.

It wasn't going to cost them anything, and they had a known entity in London, and so.

Speaker 1That's what I did, So rolled the dice, really, I.

Speaker 2Guess, so, I mean it didn't feel like that much of a role looking back, I suppose it was, but you know, I had I had, I had some clients, you know, the ten network, I had a job to do.

It was still the journalism that I wanted.

It was an inroad into a place that was really the hub of correspondence of journal of world journalism, and and I had the resources, I guess to keep me there for about a year, and I figured, well, if it all goes pear shaped, I'll be back.

And it didn't.

I kind of went from there to to Yugoslavia to Bosnia in the war.

Speaker 1Okay, so like covering in those those areas of conflict like Bosnia and different things.

Tell us about your first expre because you mentioned Neil Davis and yeah, people that correspondence.

It's a dangerous thing.

They're in there where the bombs are going off and the bullets and bullets are flying.

What was did you have to test yourself that you were comfortable with that environment, because I would imagine some people I.

Speaker 2Guess it was a bit of toe dipping.

So it started with when I met a girl in a pub in London, which is where all good start, this flamehead Irish girl who was dancing on the table and just really having a great time, and I was really I was inamateant, and so I thought i'd chatter up and started talking to her.

She told me that she was about to go on this pilgrimage, on a Catholic pilgrimage to a place called Magriagori, which was this town, a village right in the middle of a place of a region of Bosnia called hertzig Bosna, which was controlled by the Croats, and it had become a place of pilgrimage since the nineteen seventies when a group of young Croats had seen these visions of the Virgin Mary, and the place became developed a reputation for medical miracles, for spiritual insights and so on, and so pilgrim started going and they kept going all through the war.

And so Kathy Haggerty, the girl that I met, was about to go on one of these pilgrimages, and I thought it was a fascinating story.

Anyway, she said, well, why don't you come?

And I told the story.

I didn't take it seriously, but I told the story to two friends of mine, one who worked for the ABC and the other who worked for the Australian, about this girl had invited me to go on this trip.

And within a couple of days I got messages from the foreign editors of both saying, for God's sake, if you're all thinking of going, then let us know because we're in the market for freelancing.

And I thought, well, it's a no brainer, isn't it.

You know, I've got the story and the clients, and there's the girl.

Why wouldn't you go?

So I went.

I did that story, and then I started working at what I thought was THEES, although I made it to Sarajevo for a while, and I found out a couple of things.

I found out that I actually was reasonably good at it.

I had the kind of mentality I guess that helped me to operate in a place like Bosnia.

It didn't freak me out.

Yeah, the gun via the combat didn't freak me out.

I was fascinated by the people that were operating there.

I worked very closely with some of the more established correspondents who were able to show me how to get around and work and operate and survive.

I didn't spend I spent a few months in the region, but it was enough to again make help me understand that actually this was something that I thought I was capable of and really kind of interested in.

Speaker 1Yeah, found the passion.

So working as a freelancer at that stage, at what point did you get with the BBC or writers.

What was the I had some events.

Speaker 2Yeah, I had another trip to South Africa nineteen ninety four to cover the post election post Aparthei had election and again for the same clients.

And it was after that that I started thinking about getting some freelance work for BBC World Service.

My plan was to just start doing some producing work in the office in the newsroom in London and then find a place out in the field that was undercovered and go and do that.

And so I figured, rather than send my CV and have some secretary chuck it in the round file, I'd apply for a proper job.

The job wasn't important, but it was the application process that mattered.

And that way the management would have to look at my CV and think of me as a prospective employee.

And when I didn't get the job, I'd say, thanks, I'm also in the market for freelancing, how about it.

So the first job that came up a way of approaching Yeah, So the first job that came up was the Carble correspondence job, right, okay, And I remember looking at it thinking, thank Christ, I'm not because Carble at that point was in the middle of civil war.

Speaker 1There was a front line that was pre that was mid nineties.

Speaker 2That that wasn't at the end of nineteen ninety.

Speaker 1Four, okay, So it was yeah, okay.

Speaker 2There was a front line running.

So the Afghanistan was being torn apart in the civil war between rival militias rather hideen factions with a front line running right through the guts of Carble.

The Taliban had just emerged.

They just started to form in Kandahar and the far south of the country, but they hadn't really spread out of there to threaten the rest of the country at that point, and so it was a pretty wild, wild time in Carbo.

In fact, there are a few correspondents who'd spent a lot of time both in Carble and in in Sarajevo who judged that Carble was by far and away the more dangerous of the two places.

So anyway, I remember applying for it and thinking, Thank Christ, I'm not going to get this thing, and then they offered me the job.

Speaker 1Might get what you wish for.

Speaker 2Yeah, you need to be careful about that.

I was kind of flawed and also actually quite scared, but also felt there is no way, no way that I could turn this down, pass it down.

Yeah, I had to go and do it.

Speaker 1What do you We've talked about you going into the wall ones or conflict theres.

What do you see the role of media in these conflict areas.

Speaker 2So there are a whole bunch of them.

There is the classic idea of being of writing the first draft of history of being a witness.

At the time, there were only three foreign correspondents permanently based in Carble.

There was myself for the BBC Reuter's stringer.

There was another a guy who was a staffer for Asian France Press, the big French news agency, and there was a third guy called Tim Johnston who worked for Voice of America and Associated Press, and a bunch of other strings as well.

And we recognized that the three of us really controlled the world's understanding of Afghanistan and it was a pretty heavy responsibility.

We'd cover some aspect to some human rights abuses.

I remember covering a story of a mass grave that some people had uncovered, and a few months later my report appeared pretty much for Bartum in a UN Human Rights Council inquiry into Afghanistan.

So you realize that the reports that we were doing at that point were having a very very direct impact on the public's response to Afghanistan, and I think that was a heavy responsibility.

There's also I think it's a bit of a cliche giving voice to the voiceless, but there is actually truth to that.

I remember a lot of the Afghans ordinary Afghans, and that includes some of the Afghan fighters, the militiamen which it can come to find on the front lines.

They were actually grateful to someone from outside, a journalist who actually gave a damn about what they were doing, that was prepared to list sit down and listen to them, talk to them, hear their stories, and in hearing their stories and telling their stories, you're giving meaning and significance to their experience, and that I think is an important thing to do.

Speaker 1In important role role in it.

Because I know and I want to speak in more detail later on about your concerns where media is suppressed and it's not being reported objectively, like the War on Terror and different things, weapons of mass destructions issues, issues like that.

But from your personal point of view, you saw a specific role and an important role that you had had in those environments.

Speaker 2Yeah, absolutely, you know, it's it was one of those rare moments where as I said, I felt that the reporting we were doing actually did have an impact both internally and externally, and I felt that that idea of the first draft of history, accurate accounting of what was taking place as a record was really was really crucial.

Speaker 1You said that the people on the ground appreciated people giving an objective view of what was going on.

Me But later at certain stages and certainly now media journalists in those environments have been targeted because they've upset someone, or that they're seen not to be objective, or they're on one side or the other.

What's your what's your experience with that?

And so under a take on.

Speaker 2That, So I think back in let's let's it's a really interesting thought that because things haven't always been the way that you've just described.

But let's go back to nineteen ninety five, pre nine to eleven, we crossed the front lanes all the time, and it was in nineteen ninety five that the Talibhan came through and in fact started laying siege to Carble.

Now I would cross the front lines whenever I could.

Often the front lines would stabilize, things would settle down, and you'd end up with a few civilian traders so tentatively making their way across the lines.

Speaker 1So from one opposing force to the other closing force.

Speaker 2Yeah, with impunity, we were able to do it.

And part of that was because I felt that I not only did I have a response a professional ethical responsibility to do that, to make sure that we covered all of the parties, all of the side to the conflict, but also I thought it was a matter of my own safety.

I wanted because I knew it was a clean shaven white guy operating in a country full of hairy, brown skin gloves standing there, I'd stand out.

Sooner or later, someone on the other side of the front lines would pick me out in their rifle sights, and I didn't want them to feel justified in pulling the trigger.

I didn't want them to see me as as a voice for the enemy, and so it was important for me to be seen to be crossing the lines, to be seen to be talking to everyone, to exercise that neutrality and independence.

But what happened with nine to eleven was that it created a war of ISAMs, a war of ideas.

The War on Terror became a war over ideas, and that was a fundamental shift in the nature of conflict.

A lot of in most of the pre nine to eleven conflicts, there wars other stuff of the land or ethnicity, political power, that kind of thing.

But the War on Terror created a war of ideas, and in that war of ideas, the space where ideas are transmitted, in other words, the media quite literally becomes a part of the battlefield.

So journalists to target it because of the way in which they're suddenly seen as agents of ideas that various governments are hostile to.

Now, if we go fast forward to nine to eleven and post nine to eleven, the war in Afghanistan suddenly crossing the lines was a hostile act.

Al Jazeera got the first interview with the one person who had weighed that pretty much every journalist would have given their right arm for, and that was with the sum had been loud Now, again, I don't agree with the Summer Bin Loudin's ideology, but I think I would argue that it's important for us to hear from him, to have his have an interview with him, to understand his ideology, to understand where he's coming from, so that we can tackle that from a place of knowledge and understanding.

Ignorance doesn't help anybody.

And yet Al Jazeera was condemned and the US dropped a bomb on Al Jazeera's bureau and Carble for advocating what a terrorist ideology.

Speaker 1Well, and I think it started after September eleventh with President Bush came out with his statement, I think you're even with us, or you're with the terrorists, which.

Speaker 2Is exactly which exactly, and that made it a binary choice.

Yeah.

Yeah, you're either on one side of this line or the other.

And if you if you if you go and stick a microphone under someone knows who we considered to be a terrorist, then you're with them.

Yeah, and therefore you're against us.

And I think that's a very very dangerous concept.

Speaker 1And if you're happy to talk about it, one of your friends in Somalia was targeted and yeah, murdered and reasonable to suggest that targeted because of the role that she had as a journalist.

Do you want to talk us through that?

Yeah, that's deeply personal for you.

Speaker 2It's a very very difficult time for me.

But yes, I mean, I think what happened to Kate Payton, my producer, is exactly an example of the kind of threats that journals were facing in that post nine to eleven world.

So Kate and I were working together covering Somalia, which was really a byword for anarchy at that point.

This is in two thousand and five.

The government had been such as it was, had been in exile in Nairoba for many many years, and Somalia, like Afghanistan before, was being torn apart by rival clan militias, but things that stabilized to the point where the government was considering going back to Mogot Issue to reclaim its seat of government, and so we felt that it was important to produce a series of features that would help our audience understand what Somalia had become.

We thought we were that we knew it was dangerous.

We went in with eight armed bodyguards and a technical with a fifty calival machine gun mounted on the back.

We had battlefield first aid kits, we had battlefield body armor, what was necessary to get the round what we felt was necessary.

But at the same time we knew that westerners aid workers had not been targeted up to for almost ten years, and that we felt that our understanding, all the intelligence that we had was that foreigners weren't participants in this conflict, that it was a battle between clan militias rather outsiders.

But at the time a group had emerged called the Islamic Courts Union, and they'd started making very hostile noises, very anti West noises.

We just arrived in Mogot Issue and we had a free afternoon.

We went to we got some briefings from some other journalists who'd been who had also been there to cover the arrival of a government delegation that had just come to try and work out how to set up the logistics for the full government's return.

And so we thought, we'll just go around to visit their hotel and see what they're what's happening there, and see if there's anyone to talk to.

We went to the hotel.

We couldn't park inside the compound.

We're you're supposed to park off the street, but the whole street was filled with bodyguards and government and technicals and so on, including our bodyguards, and so we thought, look that it's reasonably safe parked right outside the gate.

It was literally only about ten fifteen meters into the compound.

So he walked in, had a few meetings, chatted.

There wasn't anyone really worthwhile talking to, so we decided to go and as we walked out, I stood on the curb side of the car and Kate walked around to the street side.

We called for the driver to open up and our bodyguards to mount up, and as we were waiting, there was a single crack.

Everyone dropped to the dropped to the to the deck.

There was a bit of shouting, some gunning of engines and so on.

I thought it was a bit odd.

I didn't know where the shot had came from had come from, but there was no other gunfire.

So I stood up and saw Kate slumped across the back of the vehicle, and I went round to her, and as I did, she put her head against my chest and I rubbed her back and just to say that it's okay.

It was just you know, I know, you've got a fright.

I didn't realize you'd been hit until my hand came up with blood, and so we rushed at the hospital and she went into surgery, but she never survived that.

She didn't make it out that.

Speaker 1I can only imagine what she went through, but what you went through it in doing your job.

Speaker 2It was an incredibly tough thing to experience.

But we also realized I learned later that we as far as we can tell, it was a case of mistake and identity in that another journalist, a female reporter, and the mouth cameraman a photographer, had interviewed the head of the Islamic Courts Union and one of his aides, who was a particularly hardcore radical guy, was offended by the interview and ordered a hit on her.

They left without incident, But it seems likely that we were targeted, or that the order went out to target a white female journalist and a male companion, and we fitted that description.

So it was it seems a targeted hit on a journalist for the work that they were doing.

It's just that it wasn't supposed to be us.

Speaker 1When you've been involved in an incident like that, did that make you question whether this is what you want to do?

Speaker 2No, it made me more bloody minded about Look I questioned, I suppose I questioned my own, our own decision making.

I questioned the processes that we went through, but I never really questioned the value of the importance of what we were doing.

We knew that it was dangerous.

Neither of us were naive.

We both worked in combat ones, and conflict ones were as I said, we were carrying all of the equipment that you'd need to deal with the hostile environment like that.

We weren't.

We weren't naive, and we both lost colleagues, so we knew it was dank.

Speaker 1So that that was when I say, accepted understood consequences.

Speaker 2Of Yeah, it was understood.

Now, this is not in any way to diminish what happened to Kate or the impact that it had on me.

But I also felt I felt like, screw you.

Speaker 1Yeah, you know you.

Speaker 2You you can't.

You can't shut us down.

You will not silence us.

And that's why I went back five years later to do another film about Somalia, about the crisis in Somalia, that also covered what had happened to Kate.

Speaker 1Okay, Kate's one example, There's been many.

Another one that there was no ifs or butts about it was James Foley, a journalist that was abducted and ended up held hostage, and it was clear who's a journalist that was known and he was to capitate it.

That is obviously saying well, this is what we're going to do this And what with a situation happened to James?

What did that do to the broader community of war correspondence.

Speaker 2I think I think it's it's said very very clearly that Islamists or were journalists as the enemy.

What James was doing was trying to understand what was happening in Islamic state controlled areas of Syria and Islamic state would brook no nobody that that questioned or challenged the ideology that they were perpetuating, that they were that they were using to exercise control over their areas.

And that's that's the fundamental point here, Garry.

It's it's the way in which both governments and Islamist extremists have come to regard journalism as the enemy they've come to regard in this back of ideas.

The people that interrogate ideas, that transmit ideas, that try to understand ideas, those are the people that we need to get rid of.

And as I said, it's not just it's not just those extremists.

Governments the world come to you.

Speaker 1I'm delving into this because in part it plays a role in what happened to you with your imprisonment.

That might be from a regime or the terrorist group or whatever, but it was from a government body.

Speaker 2Yeah.

Speaker 1Absolutely, And so if you're looking at it, we can't say it's a one way straight that works both ways.

Our Jazeera you mentioned that, when did you start working for them?

And just give us a history of Our Jazeera because we watch it over here and they're sort of a disconnect.

But there's a perception that they're aligned with the Islamic states more so than the Western countries.

Speaker 2Yeah, I would never have worked for them if they were alone with Islamists.

Speaker 1Well that's where I find their history quite interesting, if you could just it's fascinating.

Speaker 2So the BBC World Service produced a BBC Arabic language news service for the Arabic world, and they survived.

It lasted for a few years until the funding from Saudi's finally was pulled and the Qataris saw the extraordinary influence that World Service that the Arabic Service had for on the region and the soft power, the soft influence that it gave the UK in the region, and they recognized that the Arabic speaking world had lost something when when the BBC closed down its Arabic service.

So they basically hired a lot of those BBC journalists to set up Al Jazeera Arabic, which became the only serious news news service that was interrogating all of those Arabic language communities with real independence and integrity.

Because even I think I think of it as there as a bit of window dressing, to be honest, if you watch our deasier English, what you'll see is an organization that champions the underdog, that's very liberal in its approach to human rights, to democracy, freedom of speech and so on, which is patently frankly everything that Katara is not, you know.

But from a journalist's perspective, I didn't mind.

I didn't mind that as long as they didn't mess with my journalism.

As long as I was able to have the editorial independence that I needed to do my job, I was comfortable with that, and so I joined our de Zerra end of twenty ten covering East Africa, and it was extraordinary.

They had the resources to and the interest in covering all sorts of stories that I would never have been able to do for the BBC because it was interesting, because it was I thought, editorially sound, even if it wasn't necessarily quite as sexy as as in the way that the BBC needed to see those stories or directly connected to the British audiences.

Just to be very clear on this, by the way, very there is a perspective right in the same way that if you're sitting in London reporting the world or editing your news packages, your news stories and news programs, you'll have an anglocentric view of the world.

That's just how it is because geographically, culturally, politically, where you are influencers, how you understand relationships, and how you report there is no make no mistake.

By sitting in Doha and reporting the world, you're going to have a view of the world that's colored by that geographic position, by that cultural and political environment that you're operating in.

But that doesn't mean that they are pro Islamist.

It also does mean too, that they've got networks within these world that gives an access that other people would never have had, and they certainly exploited that.

Speaker 1Twenty ten you started working with Al Jazir, the leading up to your arrest in Cairo.

That was twenty and thirteen.

Correct me if I'm wrong, But it was just a tempor You were leaving someone over over a break, as simple as that sounds, but that's how you found yourself in Kira.

Speaker 2Yeah.

I hadn't worked in I hadn't covered Egypt before.

I didn't know the place very well.

My base was Nairobi, and Al Jazeera called and said, listen, do you mind just covering the bureau for a couple of weeks over the Christmas New Year period.

We're a bit light staffed.

Just need you to tread water, keep the stories ticking over, would you mind?

Of course I didn't mind.

You know, I was fascinated by what was taking place in Cairo and Egypt at the time and.

Speaker 1What talks through what was happening at the time there.

Speaker 2So just to one o'clock back a little bit back in twenty eleven, we saw the Spring uprising hostin will Barrack, the long standing autocrat was forced from power with that popular uprising, and the following year, middle of twenty twelve, we saw the first democratic elections in Egypt's history.

Now, the Muslim Brotherhood won those elections.

Moment Morsey became the president, the leader of the Brotherhood, and that was unexpected.

There was a product of the political system at the time, but indisputably the Brotherhood won.

Middle of twenty thirteen, like so many governments, so many revolutionary movements, they really make crap governments.

And there was a lot of discontent in the street.

It's a lot of protests some of the more conservative policies.

But by the by the middle of twenty thirteen, when we saw those street protests, the military stepped up and said listen, we're a democracy.

Now you've lost clearly lost the confidence of the people, and you've got to stand aside, and he's a gun to You had to make sure that you'd do it.

It was a coup in other words.

And so by the time that I arrived, there were a lot of a lot of violent protests in the streets between and clashes between supporters of the of the Brotherhood and supporters of the military installed regime.

Speaker 1And you your role there was to cover it, got to the location, gave the site, and cover the demonstrations and what was going on, and.

Speaker 2To cover some of the political changes that were that were that were happening.

The interim administration, the military installed administration was redrafting the constitution, for example, and that make some changes.

You know.

We'd pick up the phone and call the opposition, which was the Brotherhood, the party that was last in power, to find out their response, and then you'd go and speak to a political analyst to make sense of it all.

Speaker 1It was.

It was vanilla journalists, very similar what you're do in any democracy, just covering the different opinions.

So there was nothing that you were doing in the short time you were there that you thought I'm pushing it here.

Speaker 2Or no, in fact I was.

You know, as a journalist, when you when you get the better you know a story, the more you start to understand the edges, you understand how far you can push things before you're going to get some kind of blowback, and you can take calculated decisions about just how much you prepared to publish and broadcast.

Because I didn't know that with the Egypt I was playing with a very very straight bat, and we were very scrupulous about being factually accurate too.

I had two local guys, two local producers that knew and understood the story inside and out, that were very very careful to keep me on the straight and narrow when it came to the fact So I was pretty confident that we weren't doing anything that was controversial, that it was all very very straightforward.

Speaker 1Okay, So when did when that either misassumption or not the misassumption that's what you were doing.

But when did that unravel?

Speaker 2So December twenty eighth, twenty thirteen, I was about to go out for dinner with a friend of mine, a BBC correspondent who was also in town over that period, who I hadn't seen for a while, and I was forward to catching up.

I was getting dressed when there was a knock on the door.

I didn't think too much of it.

If anyone ever wanted to speak to me, they'd use the phone.

But you know, there was a rather rather more urgent knock soon after that, a lot more forceful.

I remember cracking the door open, and as I did, it was flung open as if there was a powerful spring behind it.

Yeah, and the room was filled with I had ten guys.

I still don't I still don't know.

Speaker 1I'm even comprehending what was going on.

Speaker 2No, they barred their way in, they moved.

They weren't playing clothes, so that I didn't know initially if they were cops or who they were.

But they moved with a professionalism that suggested that these guys weren't just a bunch of thugs that were raiding.

Speaker 1Had some purpose.

Speaker 2They had purpose and discipline and leadership.

There was one guy who was very clearly in charge.

Speaker 1And what did they What did they say to you?

Speaker 2What?

Oh?

They just demanded to see that demanded I open up the safe.

They demanded that I basically they ransacked the place.

They didn't ask me too many questions at that point, and just I wanted to see that they had an arrest warrant, what was going on on a search warrant.

They asked me if I spoke or if I could read Arabic, and of course I couldn't, so they shrugged and said, well, there's not much point in showing you.

Speaker 1What we've got, and they had to make any phone calls or.

Speaker 2No phone calls, no no communication whatsoever.

We were taking down into another room in the hotel that had been commandeered by the police, and there was my other colleague, Mouhammad Fami, who was a producer, who had also been detained in another from another room at the hotel that we were using as an office.

And then when they started asking his questions, you know what we were doing in the hotel, whether we had licenses for the question and why we were you know, why we were using while we were working for Al Jazeera.

Speaker 1I looked at the questions that sounded like you had reasonable, reasonable answers for them.

Yeah, so I'm looking.

I've got some of them down here because I'm thinking, Okay, I'm trying to be objective.

I'm trying to look from their point of view.

But there these are the questions they've asked you.

Why are you're hiding in the Marriott Hotel, What are you doing with the Muslim Brotherhood, Why don't you have press accreditation?

Where is your license to operate this equipment?

Why are you're working for Al Jazeera?

All of which you've got reasonable answers for.

Speaker 2Yeah, there's there's nothing sinister about any of that stuff.

There didn't seem to be any agenda, which is also part of the reason why I thought, look, this is going to be over fairly quickly.

There are good answers to all of these questions.

Younsidered or later they'd realize that that someone had screwed up, or that you know, that overstepped the mark, or you know, they'd rattle the cage and we'd be allowed to go home.

Speaker 1But that definitely wasn't the case.

So where were you taken?

After the sort of informal question.

Speaker 2So we were taken into a police cell, horribly crowded, overcrowded place with I think they're about eight guys in that cell, which is nothing compared to the following night, where there was sixteen guys in a in a two meter square box.

Speaker 1To describe that, because I've seen people when they've been arrested, and it's intimidating when you're in your own country and you know what you've been arrested for.

You're in a foreign country, but you've got a worldview and you're well traveled, but still that unknown and then being taken to a detention center, prison or whatever and put in a cell with that many people, What was going through your mind?

Speaker 2Yeah, that was pretty scary.

I was so the second sell in particular, so fammy and I were together in the first cell and we had the night there in that box that it was very, very tight.

We were like literally like sardines.

Speaker 1You know.

Speaker 2You couldn't you just lying down.

You all had to roll over together.

You couldn't.

You had to lie on the same side.

You had to coordinate movements.

But the following night was even worse.

Family went was taken to a different prison.

I was taken into it, this police cell.

It was about eight foot square, as I said, to meet, a square no reading, no, no furniture, no you know, just a leaky tap and leaky sink in one corner tap and a bother stinky squat toilet and the other and the door, and that was it.

And in that concrete box there were sixteen.

Speaker 1Guys eighty eight.

Speaker 2Yeah, it was.

It was impossibly cramped, and some of the guys had been in that cell for the better part of six months and they were quite literally losing their minds.

The kind of psychological pressure of confinement, of that of that type of confinement is immense, and I realized then that this was getting pretty serious.

There were some students in there who had also been a lot of the guys had been picked up in the sweeps that the military had been doing looking for people who were suspected of being wasn't Brotherhood sympathizers, but we you know, And so I had a sun inkling of what was going on, but didn't know a great deal about it until the next day when we were taken to the National Intelligence Director for interrogation.

And that's really when I learned the charges that we were facing.

Speaker 1And did you have your employer our JASEA were ero?

Were they informed or the Australian Consulate.

Speaker 2They were yes.

So the Australian consul, the Australian Embassy center, a consular official to the National Intelligence Director at the next day, so Al Jazeera was obviously aware.

I had no idea what they knew.

I had no idea how much information they had or what they were doing.

All I knew was a to the official had been alerted.

That was a pretty difficult conversation just because it was a limit to what they could actually tell you.

Speaker 1I've heard that from quite a little group of colleagues and other people that have been arrested in foreign lands.

It's you think, Okay, it's all going to be sorted out now, and they basically walk in and go, we can inform your family and not much not much else.

Speaker 2Yeah.

Yeah, And to be fair to the constant the individuals, because I think it's pretty difficult for them too, because they'd love to help them.

A lot of the time that you know, they're kind of rolling their eyes because most of the people that they're having to deal with, they're Aussies who've I don't know've gotten themselves drunken and crashed a motorbike into someone's car or done something stupid, you know, gotten broken, maybe shoplifted some food or done something like that, you know, And so it's really difficult in those circumstances.

But even in cases like mine and Sean's and chang Lais and others.

Is a domestic legal process that you're stuck in.

And apart from monitoring and observing what you're going through, and apart from telling your own family what's happened and perhaps giving you a list of English speaking lawyers, there's nothing really that they can actively do.

They can't directly intervene, certainly not without significant political and diplomatic weight behind them, which we didn't have at that point.

Speaker 1So charge is how long can they hold you?

Could you even find out.

Speaker 2That or was it?

Speaker 1Yeah?

Speaker 2So there was a kind of six week process.

It could be held for six weeks for questioning before you had to go before a magistrate and have the case reviewed and they would either throw it out and release you or the charges the tension period would be renewed.

And so yeah, you kind of stuck within that interrogation process.

Speaker 1Where is like and where are your house?

Have you been moved from the eight by eight?

Speaker 2Yeah?

I was moved from that cell to a place called Limentura, which was the political wing of one of the political wings of the Torah prison complex, and I was placed in solitary confinement but also learned through some of my neighboring the inmates in the wing who would come past the outside of the door and speak through the door, whispered through the door when there were no guards around, and tell me what was going on.

And they said that I was in Limentura alongside a lot of the leaders of the of the Arab Spring uprising, the pro democracy activists, writers, poets, activists, lawyers, trade unionists, all sorts of sort of civil society actors, I guess is the way that you might describe them, who were all there on terrorism charges and espionage charges and so on.

But it was in I was in solitary confinement.

So you know, that's a that's a that's a pretty tough thing to.

Speaker 1Us through that.

When you say so litry confinement, what what did that involve?

Speaker 2Well?

Nothing, no.

Speaker 1Question, dumb question answer.

Speaker 2You stuck, Yeah, exactly.

No, really material you've got you know you've got no, you've got to you've got to look after your own mind.

I mean, one of the things I remember, but it was pieces of advice that I had from from one of the other inmates, from an extraordinary guy called who said to me that at one point when I was told him that I was really struggling.

In one of these conversations through the through the door, I told him, I'm really struggling.

I I've got because the thing that happens in solitary is the absence of anything else to do with your mind.

You start to play the movie of your life on the walls of the cell, and I remember previous relationships, you know, the people, previous exes that I'd let down, Kate's murder, all of that stuff was going through my mind, and you know, starting to think, well, because I couldn't see any connection between the reality of the form, the ordinary journalism that we've done, and the ridiculous terrorism charges that we were facing, I started to think, well, maybe this is the universe, right, this is this is this just can't.

Speaker 1That's the way the way your mind plays.

Speaker 2And I was saying this to alone.

He said to me that this and you you're you're not going to make it through this unless you're able to make peace with yourself, which was perhaps the most important.

I think.

Speaker 1I actually what that relates to.

I pulled the quote out of out of your book and that and I'll just read that out because I think it speaks very much to what you're just talking about.

There.

In the time I've burned in prison, I've learned a few things about getting through it, and the biggest lesson is this, you cannot make it through prison.

You will not survive, certainly, not with your centery intact, unless you are able to make peace with yourself.

And so it's almost like an enlightening moment, isn't it that.

Speaker 2It's funny you say that, because remember there was another moment when I was saying to one of the guys that came outside the cell that I was really finding trying confinement really hard.

And he said, I think he misunderstood what I said.

And he said to me, like yes, he said, he said, you know, monks and try for years to find solitude, to find the space to think.

And he said, it's a blessing, isn't it.

Speaker 1I always look on the bright side of light.

Speaker 2Well, yeah, exactly forty days and forty nine.

It's the kind of classic period and the desert of self reflection and meditation.

Speaker 1But you had to dig deep.

There was things I think you had delved into Buddhism and meditation previously before you were locked up, and you found some solace in those practices and those thoughts.

Speaker 2Yeah.

I actually think it was the Buddhist meditation that really helped keep my sanity intact.

Yeah, the kind of approach to sitting still and to watching your thoughts almost as an independent observer, learning to see the thoughts as a kind of detached witness, not seeing them, not owning the thoughts, and starting to recognize them as just functions of what the mind does rather than getting invested in them.

That was a really crucial part of surviving.

Speaker 1Yeah, it's interesting how you can dig deep in those situations.

Also, you trained as much as you could depending on the environment, mentally, running like physical, trying to Yeah, absolutely once as well.

Speaker 2Absolutely you have to.

You know, if we go back to those guys that have been in this in that tiny eight by eight foot square, cel I realized that that a lot of them had also lost contact with the diurnal rhythms, with the daily rhythms.

They're up until three, four five in the morning, joking, laughing, crying and doing all sorts of hysterical things and sleep through the day.

And I realized what was really important was to hold on to the dianal rhythm.

To get to the end of the day and be physically tired and sleep at night and then wake up early and be physically active during the day.

And that meant exercising, whether it was running on the spot or when we were finally when I was finally out of the cell, doing laps up and down the cell corridor, around the exercise yard, always doing whatever I could to be physically active, so that come the end of the day, I'd be exhausted and tired and ready to sleep.

Speaker 1And I would imagine finding some of the group of purpose.

That's what a lot of mental health experts always if people are going through tough times or have purpose.

Speaker 2It's purpose and discipline.

But it's also about filling time too.

It's the empty time that does your head in.

And so the exercise was really crucial way of filling the time in a way that I felt was productive.

We'd also do a lot of creative stuff as well, you know, deliberately creative time.

I'm saying that through this period of the day, we will now do creative things or play games, things that would keep us mentally active, you know.

I remember.

So sometimes the food would come wrapped in aluminum foil and you know, but aluminum foil has a shiny side and a mate side.

And I discovered that foil actually sticks quite well to the prison walls if you smear it with soap.

Speaker 1And so that's right, you made that.

Speaker 2So we made these big murals on the wall.

Speaker 1Which reflect the light better than you anticipation.

Speaker 2Yeah, it was beautiful.

Speaker 1That's the architect from your father coming through.

Speaker 2But Gary, here's the thing in a way that I didn't understand suddenly, and it was only afterwards I realized when I was reflecting back on it.

We started to deal with mind, body, and soul.

Yes, those three key elements I guess of of survival.

Speaker 1When it's all stripped back, that's what it comes down.

Speaker 2That's what it comes down to, and you have to manage all three.

Speaker 1Yeah.

Interesting, Well, I think we might take a break here.

I'm going to leave you in prison at this stage.

I'm sorry.

I had to hope to get you out of prison before the end of part one, but we're going to have to leave you in prison.

When we come back, we're going to talk about your battle for freedom, because it was a battle and there were some big decisions to make, including about going on a hunger strike.

The people that you were arrested with had different strategies on how to get through this or fight the allegations against you.

I also want to ask you what it's like having a famous Australian actor play you in a movie about your life and what your thoughts on him, because I can't get Rake out of my mind.

Either character that Richard Roxburgh played in that Rake or the last person he actually played was a real life person he played was Roger Rogerson, notorious criminal, and he played him very well.

Speaker 2So yeah, notoriously corrupt cop exactly.

Speaker 1He's probably more fitting.

He's passed away now, but yeah, so we'll have a bit of fun talking about that.

And I also want to delve into your thoughts on journalism because that's something you're very passionate about and the thing the importance of journalism and journalists have been allowed to tell their stories and the impact that can have.

So we'll do that when we get back to part