Episode Transcript

Actually has a habit.

If she gets in trouble by, someone should make accusations against that person.

Speaker 2Organ City sits at the end of the Oregon Trail.

We're countless pioneers once gathered to catch their first glimpse of the promised land.

This historic community of around thirty seven thousand is nastled along the banks of the Willamette River just south of Portland.

It's always prided itself on being the kind of place where American dreams come true.

Tree lined streets wind through neighborhoods filled with modest ranch homes in well kept split levels.

The newll Creek Village Apartment Complex embodies the working class spirit that built Oregon City.

The one hundred and twenty five unit apartment complex was built in the late ninety nineties and was designed to provide affordable housing to single mothers, working families, the mentally ill, and people with disabilities.

The complex sits along a quiet stretch of road, surrounded by toring Douglas Firs and western red cedars.

Here, single mothers work double shifts to provide for their children.

Neighbors help neighbors, and kids walk safely to the nearby bus stop.

Each morning without a second thought.

Parents know their children's friends, teachers know their students' families, and everybody looks out for everyone else.

The apartment complex playground is almost always filled with laughter on weekend afternoons, while the nearby creek provides endless adventure for imaginative young minds.

But in the early months of two thousand and two, newl Creek Village would become the epitome of every parent's worst nightmare.

The community all came together to search for a missing girl.

Two months later, another girl vanished.

Somewhere among them lived a predator.

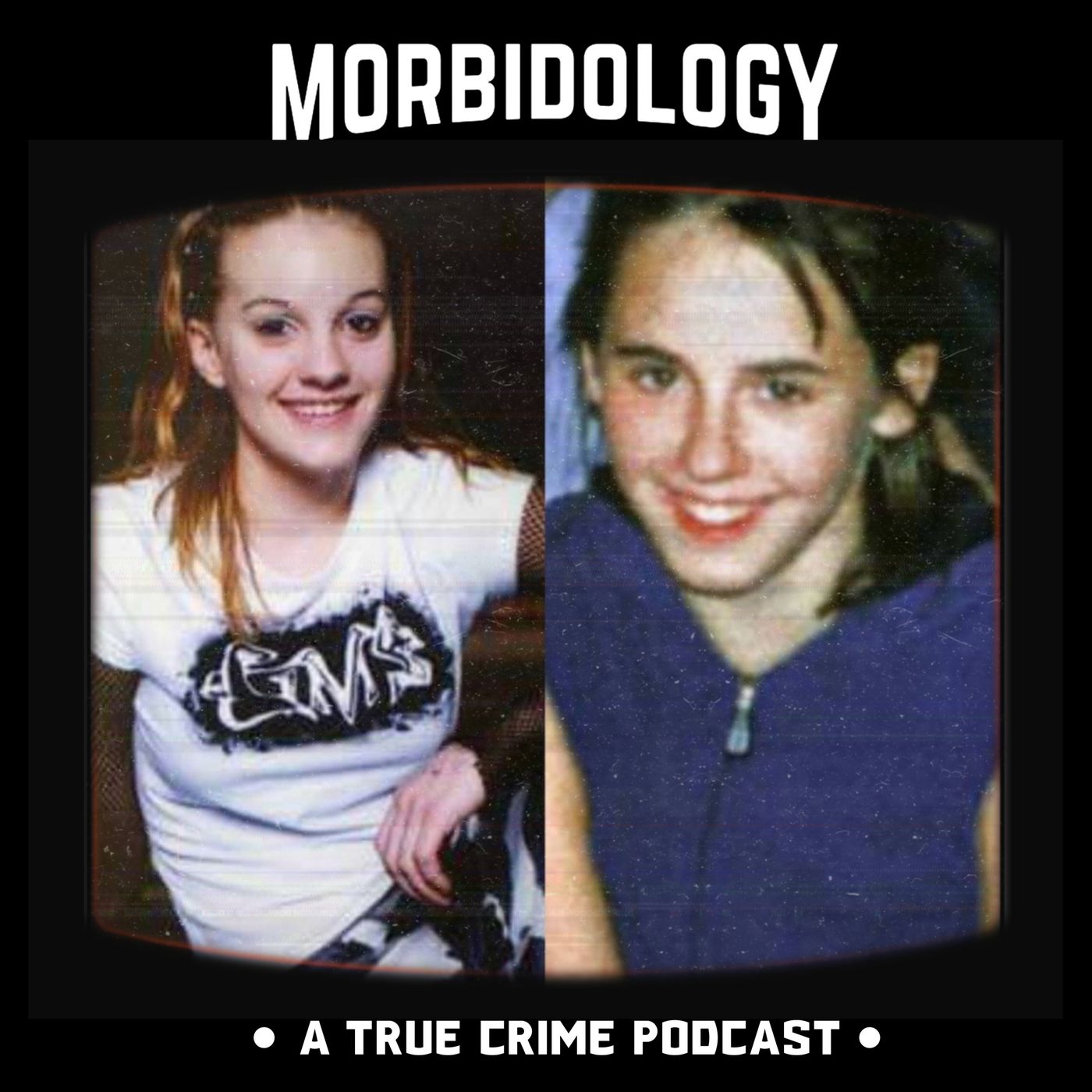

Ashley Marie Pond was twelve years old, and she wore sweatshirts to school even when it wasn't cold.

It was a habit born from the particular self consciousness that settles over children who've learned too much about the world too soon.

Yellow was Ashley's favorite color, which seemed fitting for a girl her family remembered as happy and bubbly.

The apartment at Neil Creek Village was home to Ashley, her mother, Laurie, and two younger siblings, six hul Miranda and eleven year old Brianna.

Ashley's story began thirteen years earlier, when her mother, Lorie Davis, was barely sixteen, almost a child herself when Ashley entered the world.

For those first precious years, Ashley lived with Laurie and David Pond, her mother's high school sweetheart who eventually became her stepfather.

To Ashley, David was simply Dad, the man who gave her his name, and for a while something that resembled stability.

But families, just like the apartment buildings they live in, sometimes have foundations that crack under pressure.

When Ashley was seven years old, the family fractured, Laurie and David's marriage dissolved, and suddenly Ashley found herself caught between two worlds.

Weekdays were spent with her mother in the apartment complex, and weekend visits with her biological father, Wesley Roger Junior.

She was four years old when she met her father for the first time.

It was an arrangement that look normal on paper, the kind of custody schedule that fills family court calendars across America.

Nobody suspected that these weekend visits would become something else Entirely.

By two thousand and one, Oregon City Police had become uncomfortably familiar with the family's dress.

It calls in just one year, a number that speaks to chaos, to a household where things were unraveling faster than they could be mended.

In two of those cases, anonymous callers had asked police to conduct welfare checks on a child that had been locked outside.

A child was Ashley.

Shortly thereafter, another call came in to report that Ashley was outside the apartment door crying.

In two other instances, Child Protective Services had requested a police check on the welfare of Ashley her siblings.

The records painted a picture of a girl that was caught in his system, that saw the symptoms, but somehow missed the disease.

Ashley's biological father, Wesley, had been sexually assaulting her since she was seven years old, turning those court mandated visits into a recurring nightmare.

But Ashley was braver than anybody knew.

In early two thousand and one, she found the courage to speak up about what her father had been doing to her.

Medical examination noted physical trauma that was consistent with sexual abuse.

On the fifth of January two thousand and one, Wesley Rocker Junior was indicted on forty counts of rape and sexual abuse spanning four years.

It should have meant justice.

It should have meant that Ashley's courage in coming forward, would finally protect her.

Instead, this system failed her spectacularly.

On the sixth of September two thousand and one, just months after Ashley had summoned the strength to expose her father's crimes, Deputy District Attorney Chris Owen dropped all forty felony counts in exchange for a play of no contest to attempted unlawful sexual penetration.

Lesley received just one hundred and twenty months of probation, no jail time, no prisons entance, just probation for four years of systematically abusing his own daughter.

Actually had spoken up, and the man who had stolen her childhood walked free.

Yet somehow, Ashley continued to show up to seventh grade at Gardener Middle School.

She continued to practice with the dance team, continued to make plans with friends about becoming veterinarians together.

At school, actually found her sanctuary on the dance team.

The gymnasium became her second home, filled with the sound of sneakers, squeaking against polished floors and hip hop music her preferred soundtrack.

She worked hard on her routines and made the food of friends.

These girls became her chosen family, the ones who knew that Ashley, who laughed and hugged freely, who dreamed of college and careers saving animals.

The contradiction that defined Ashley was heartbreakingly simple.

She loved to give hugs, but she was very shy with strangers.

She was the girl who would wrap her arms around her friends without hesitation, but who might duck her head and mumble when meeting somebody new.

It was a twelve year old's way of navigating a world that felt far too big and far too small at the same time, a world where the people who should protect you sometimes don't.

The year before Ashley turned twelve had been her most difficult yet.

With the trouble at home mounting, Ashley had become more reserved, more quiet.

Her skill work started to suffer as her concentration fragmented under the weight of secrets that were too heavy for a child to carry.

The happy, bubbly girl her family remembered seemed to be retreating somewhere deeper inside herself.

But then as two thousand and one turned to two thousand and two, something changed.

Acshally became more talkative, more open.

She started getting her homework done on time, making sure that it was completed well.

Her teachers noticed the improvement.

Her friend saw glimmers of the old Ashley returning.

Ashley seemed to be emerging from the shadow that had fallen across her eleventh year, but something even worse was just around the corner.

Wednesday, the ninth of January two thousand and two, dawned cold and charp in Oregon City.

Ashley woke up, pulled on her jans in a sweatshirt, and prepared for another day of school.

Laurie's boyfriend, James Cayley, had spent the night.

He left for her work at around seven fifteen a m.

The two younger girls had already left for school.

By the time he left, Ashley was running late.

A roundy at a m Ashley said goodbye to her mother and headed out the front door.

The walk to the bus stop take less than ten minutes up the hill from Neuill Creek Village.

It was a routine that Ashley had taken hundreds of times before.

Passed the same apartment buildings in mailboxes and parked cars, But that afternoon, Ashley never returned home from school.

When evening came and Ashley still hadn't walked through the door, Laurie called the school.

Her heart felt to the pit of her stomach when she learned that Ashley had never arrived at school that morning.

She immediately called police.

The search for Ashley got under way quickly, and the FBI became involved.

They took staymen from Ashley's family and conducted a thorough search of the apartment.

One initial theory was that Ashley might have run away from home, given the police call outs the year before and what happened with her father, an unreasonable assumption.

Children flee dysfunction all the time, seeking safety in motion when they can't find it in stillness.

But according to those who knew the family, Ashley and Laurie had worked through their problems.

The improvement in Ashley's behavior, her renewed focus on school work, her increasing openness.

None of it suggested a girl that was planning to disappear.

Neighbor jasyindamac Load had noticed the changes too.

She admitted that Ashley had been snotty and talked back to her mother during the difficult period, but she didn't believe that Ashley would run away, not now when things seemed to be improving.

She said to the media, She'd worked too hard to run away.

Her and her mom have been through helen back to work that hard, and to run away makes no sense to me.

The evidence supported this assessment.

Ashley hadn't taken any clothing with her, she hadn't reached out to any friends.

She'd simply vanished without a trace, as if the morning air had swallowed her whole.

Detectives began methodically scarring through the neighborhood, walking the same route that Ashley would have taken to reach the bus stop.

They examined every doorway, every alley, every possible place where a struggle might have occurred, where evidence might have been dropped, but there was nothing.

The search party then expanded their radius, focusing on the wooded area that surrounded the apartment complex.

They were assisted by explorer scouts, who methodically scanned the foliage, calling out Ashley's name until their voices grew hoarse.

Days trickled past, each one carrying less hope than the one before.

Detective Gary Harris, who had seen too many of these cases to maintain illusions about happy endings, summed up their frustration when he said, we were hoping we would come up with more, but we've not actually come up with anything we can use.

Thousands of missing powers and flowers were printed and distributed throughout Oregon City and beyond, each one featuring Ashley's skill photo, the image of a girl who looked younger than her twelve years, with dark hair and eyes.

So after I had my baby girl Amber, last year, I noticed that my hair was shatting like mad.

Every time I'd wash my hair or rub my hands through it, there were just handfuls coming out.

It was honestly unsettling.

I knew that postpartum shatting was a thing, but actually experiencing it was a different story.

I started taking Nutrifall's postpartum formula, and I've genuinely loved it.

I've seen less shatting, and my hair just feels healthier.

It's been a confidence boost during a time when I was already dealing with so much change.

Here's the thing, holidays can get busy and overwhelming quickly, and thoughtful gifts that encourage self care, always stand out.

Neutrafil makes an ideal gift for anybody who deserves a boost of confidence heading into the new year.

Neutrifil is the number one dermatologists recommend that hair growth supplement brands to buy over one and a half million people.

They have formulas for everyone, postpartum, menopause, men, and anyone looking to support their overall hair health.

And you can feel great knowing that their supplements are backed by peer reviewed studies and NSF content certified.

Give the gift of confidence this holiday season with Neutrophil, whether you're trading yourself or someone on your list.

Visibly healthier, thicker hair is the gift that keeps on giving.

Right now, Neutrofoil is offering my listeners ten dollars off your first month subscription plus free shipping when you go to nutrifoil dot com and use the promo code Morbidrology ten.

That's neutrofoil dot com promo code more Biology ten for ten dollars off.

Massive signs with Ashley's face were posted along Beaver Creek Road, turning her disappearance into a public play for information.

The days transformed into weeks and detectives were no closer to finding Ashley than they had been on day one.

The trail, if there ever had been one, had gone cold.

Then, on the twenty fifth of January, sixteen days after Ashley vanished, investigators enlisted the help of the cadaver dog named Klaus.

The German shepherd methodically sniffed along the doors of the apartments in the complex where Ashley had lived, his handler watching for any sign that the dog had detected the scent of death.

Claus then worked the perimeter of the wooded area that surrounded the apartment complex, his nose trained on secrets the ground might be hiding, But the dog found nothing, no hit, no indication that Ashley was anywhere in the vicinity of her last known location.

It was as if she had simply ceased to exist the moment she stepped out of her mother's apartment.

Ashley's friends at Gardener Middle School were devastated by her disappearance.

The dance team that a Binner second family now felt incomplete.

Among those friends, none was more affected than thirteen year old Miranda Goddis.

Miranda lived in the same apartment complex as Ashley, just close enough that their mothers often ran into each other by the mailboxes.

She immediately joined the search efforts for her missing friend, her face becoming a familiar presence among the volunteers combing the woods and distributing flyers round to even smoke with the media.

Speaker 3We were close, like off and on, but not all the time.

Speaker 1Did she ever talk about comings?

Speaker 3Yeah, I'm known her for like since like third or second game, and there's yeah, definitely, I want to talk about.

What do you think happened that morning or what actually happened that morning Wednesday?

Yeah, that one morning, whish basically I will know what happened.

Speaker 1I don't know.

Speaker 3I don't know what happened.

Let's know that she disappeared right away.

I got kidnapped or something.

Speaker 1Did you talk about running away from you said.

Speaker 3That she might have.

Yeah, she told her, my little sister that she though we before to do that.

She told her that she was going to run away.

So, but she's been gone for so long while because it seems like she got kim off or something.

Speaker 2We others might have gone to lose hope.

As the day stretched into wakes, Miranda refused to give up on Ashley.

There was something both heartbreaking and admirable about watching a thirteen year old girl stand in front of cameras begging for somebody to come forward.

She spoke with a kind of desperate hope that only comes from somebody who truly believes that the person they love might still come home.

The dance team organized a fundraiser to help with the search efforts, and it was scheduled for the twenty third of March two thousand and two.

It was meant to raise money for a reward fund, a concrete way to channel their grief and helplessness into action.

Miranda was supposed to perform as part of the fundraiser, another chance to honor her missing friend and maybe somehow bring her home, but Miranda would never make it to that fundraiser.

Miranda Diane Garis was thirteen years old at five foot four.

She was tall for her age, with dyed blonde hair that caught the light and brown eyes.

Her friends all described her as outgoing, funny, and very loving.

Like Ashley, Miranda lived at Neil Creek Village with her mother, Michelle Duffy, her older sister, Marissa, and younger siblings.

Michelle and Miranda's father were divorced, and Michelle worked as an office manager for an engineering firm.

Miranda's father, Jason, on the other hand, had been convicted in nineteen ninety five of sexually assaulting two girls.

When police came to arrest him, he grabbed Miranda and used her as a hostage.

Michelle described Miranda as a real happy kid.

She loves dancing and bouncing around and always smiling.

She would dance to anything from Janet Jackson the Pink.

Miranda had dreams to one day become a model.

She also had a rebellious streak with a pierced to belly button and tongue.

At just thirteen years old, she looked much older than her age, something her mother worried about when it came to boys.

She recollected, she looked eighteen or nineteen.

At the town Center, I tell guys she's thirteen.

Miranda and Ashley had been friends for a few years.

They lived in the same apartment complex, rode the same boss, and danced together.

Miranda was the more aging one, the girl who cracked up her dance class with goofy moves.

Ashley was the one who preferred to be in the background.

Both girls carried secrets that were too heavy for children to bear.

They'd both endured sexual abuse as young children.

In nineteen ninety nine, Miranda's mother's ex boyfriend, Brett mcgannay, was indicted on seven counts of sexual abuse involving Miranda.

He later played a guilty to a single count of first degree sexual abuse and was sentenced to seventy five months in prison.

The state removed Miranda and her sisters from her mother's care, and they lived with foster parents for around eighteen months before they were allowed to return home.

The two girls had a shared trauma that perhaps drew them even closer together, but friendship at thirteen can be complicated, especially when tragedy strikes.

As the weeks passed after Ashley disappeared, Miranda found herself caught in a storm of conflicting emotions.

She'd been upset about the attention that focused on Ashley.

She even thought at one point that Ashley had just run away.

Her mother recollected she thought she ran away and didn't want to come back.

It wasn't that she didn't want her friend found.

It was that she'd felt forgotten.

In the wake of Ashley's disappearance, the frustration built inside her until one day she told her mother Michelle, I'm going to go get kidnapped.

It was the kind of thing that thirteen year olds say when they feel overlooked, when they want attention, when they don't fully understand the weight of their words.

Miranda had become angry at Ashley for causing so much turmoil, for disappearing and leaving everyone else to deal with the chaos and fear that followed.

Her life had changed.

She took her mother's cell phone wherever she left the house and stopped going anywhere alone.

She didn't understand that Ashley hadn't chosen to disappear, that her friend hadn't wanted to become the center of a tragedy.

Children often believe that they're invincible the bad things happened to other people in other places at other times.

Even with Ashley's disappearance casting a shadow over Neil Creek Village, Miranda probably didn't truly believe that the same darkness could reach for her.

On the morning of the eighth of March two thousand and two, Miranda sat at the kitchen table in her bathroom eating breakfast while her mother, Michelle, prepared for another day at work.

It was a routine morning.

Miranda told her mother about the dead ahead.

She said ed school got out at one pm and she planned on heading to her friend's house.

She also had to return to school for a three pm dance rehearsal.

Michelle reminded Miranda to lock the apartment door when she left for school, and then headed out at seven point thirty am.

Miranda was supposed to leave around eight am, following the same route up the hill to the bus stop that Ashley had taken nearly two months earlier, the bus stop that had already claimed one girl.

But as Miranda finished her breakfast and got dressed for school, she had no way of knowing that her casual complaint about wanting to be kidnapped was about to become a horrifying reality.

Like Ashley, Miranda never made it to that bus stop.

The similarities between Ashley and Miranda's disappearances were far too obvious to ignore.

They were two young girls living in the same apartment complex who vanished while walking to catch the skill bus.

The constant stream of police officers that had died down since January was back flooding Nurl Creek Village apartments once more, with flashing lights and the grim machinery of investigation.

The same volunteers who had searched for Ashley came together again, their faces more haggard now, their hope more fragile.

They searched the same streets, combed the same wooded areas, called out into the same silence that had swallowed their voices two months earlier.

This time they called for Miranda, but the forest gave back nothing but echoes.

Miranda's mother, Michelle, stood before reporters and said, it's very frustrating.

We've talked to anybody and everybody.

I hope she calls to us to let us know she's okay.

We've cried a lot today.

Initially, investigators considered the possibility that Miranda had staged drown disappearance.

After all, she had made that haunting comment about getting kidnapped.

But like Ashley before her, Miranda hadn't taken any of her belongings.

Her friends all insisted she'd been looking forward to an upcoming dance competition.

The theory crumbled under the weight of evidence that suggested something far more sinister.

The FBI set up a commands center on the second story of the Oregon City Fire Department.

As agents and detectives worked around the clock searching for the two girls, the atmosphere at Neil Creek Village became suffocating with fear and suspicion.

Jennifer Smith, the mother of three daughters, captured the terror that had settled over the community, stating, if I didn't have a lease, I'd be out of here tomorrow.

She wouldn't let her daughters play outside anymore.

The specter of a child abdoctor loomed heavy overhead, and parents were terrified their child would be next.

While detectives hadn't officially declared that the girls were abducted, that was now the main theory.

Somewhere in their midst lurked a press editor who knew exactly when and where to strike somebody who could make children disappear in broad daylight without anybody saying or hearing a thing.

Brandy Williams voiced what many residents were thinking when she said, people are very suspicious of it being someone around here, someone who knows the neighborhood kids and their schedules.

As the days trickled past with no trace of either girl, the FBI made two chilling announcements.

They believed the cases were linked, and they believed both girls were abducted.

More disturbing still, they were convinced that Ashley and Miranda knew their abductor.

Chief Gordon Herres explained the logic that led to this conclusion.

If it was a forcible abduction, at least at that location, somebody would have seen something or heard something.

The apartment complex was typically busy during the morning rush with people heading to work in school.

Both girls' families insisted their daughters wouldn't have been forced into a vehicle without screaming and fighting back, yet nobody heard a thing.

A family friend of Miranda's reinforced this assessment and said she's a tough person.

She would have screamed at the top of her lungs.

The implications were terrifying.

If the girls knew their abductor, if they had gone willingly, at least initially, then the predator wasn't some stranger lurking in the shadows.

It was someone familiar, someone trusted, someone who moved through their community undetected because he belonged there.

In an effort to trace persons of interest, detectives searched both girls computers.

Their disappearances aired on America's Most Wanted and Unsolved Mysteries, broadcasting their faces to millions of views across the country.

Shortly after the show aired, the FBI announced a fifty thousand dollars reward for information about the disappearances.

Special Agent Charles Matthews directed a message at the kidnap stating we will find you and we will arrest you.

But as it turned out, they wouldn't have to search very far at all.

On the thirteenth of August two thousand and two, more than seven months after Ashley's disappearance, in five months after Miranda vanished, a house close to Nuril Creek Village apartments was suddenly enveloped in crime scene tape.

Detectives could be seen coming and going with bags of evidence.

The home belonged to thirty nine year old Ward Francis Weaver, the Third.

A few hours earlier, a woman wrapped only in a blue plastic torp came running from Weaver's home.

She flagged on a motorist who took her to the Payliss shoe source in the nearby Berry Hill shopping center, where she stumbled inside.

Hysterical and shaking.

She had red marks and scratches covering her neck.

The woman was the nineteen year old girl friend of Ward Weaver's son, Francis.

Between sobs, she told store employee and native Stuart that Ward Weaver had raped her and tried to kill her.

The young girl's story was as calculated as it was brutal.

She had gone to Ward Weaver's home to pick him up.

He told her he had forgotten something inside and asked her to come in.

When she was inside, he asked her to follow him into the bedroom because he wanted to show her something.

Once inside, Weaver raped her and then tried to strangle her.

She had managed to fight back, pulling his hair and bashing his head to fend them off, before escaping into the afternoon, wrapped in nothing but a torp.

But that wasn't the only call that police received that day.

Around the same time, a nine one one call came in from Weaver's nineteen year old son, Francis.

His voice was shaken as he told the despatcher something that would finally break the case wide open.

His father had claimed to have killed Ashley Pond and Miranda Gaddis, and he was planning on fleeing to Mexico.

Ward Weaver didn't get very far.

Detectives tracked him down and arrested him as he drove north on Interstate two five.

As it turned out, Weaver was already very familiar to detectives who were investigating the disappearances of Ashley and Miranda.

In fact, he had been hiding in plain sight all along, a predator who had filled everyone, including the investigators who should have seen him coming.

Ward Francis Weaver third was born on the sixth of April nineteen sixty three in Humboldt County, California, to Trish and Ward Weaver Junior.

From the moment he drew breath, he was destined to inherit a legacy that would make most families change their names and flee to different states.

But the Weavers weren't most families.

They were a dynasty of predators, a blood line that seemed to pass violence in sexual devians from father to son, like an heirloom that nobody wanted but everybody received.

In nineteen sixty seven, when Weaver was just four years old, his father abandoned the family.

It was an abandonment that might have seemed like mercy, except that Word Weaver Junior's absence didn't spare his son from the family curse.

It only delayed its manifestation.

Ward Weaver Senior, the boy's grandfather, had raped his own sister and two of the family's granddaughters.

Dorothy Weaver, his grandmother, harbored a dep hatred of men.

One day, she grabbed a butcher knife and declared she wanted to cut off all of their penises.

Despite his abandonment, Weaver still idolized Ward Junior, even when his father sat on death row.

In nineteen eighty one, when Weaver was eighteen years old, his father, Ward Junior, murdered eighteen year old Air Force recruit Robert Radford and his twenty three year old girlfriend, Barbara Lavoy, who he also raped.

Ward Junior had found the couple stranded a long Highway fifty eight in California, where their car had broken down.

He beat Robert to death on the spot, then kidnapped, raped, and sodomized Barbara before killing her and burying her in his back yard.

The bidders only came to light when Ward Junior was in prisonerretre serving a sentence of forty two years he had picked up two other runaways and arranged for a friend to shoot one of them, while he repeatedly raped the other, a fifteen year old girl, before letting her go.

Ward Junior was convicted in nineteen eighty four in Kern County Superior Court for first degree murder, but the true scope of his crimes may never be known.

He was a truck driver whose route matched with twenty six Unsalt hitchhiker murders, though he was never charged with any other crimes, the implication was chilling.

War Junior may have been a serial killer whose cross country roots became hunting grounds for young people unlucky enough to need a ride.

This was the father that Weaver looked up to.

This was the man whose approval he craved, whose path he would eventually follow with horrifying precision.

Weaver's mother went on to marry another man, Bob Budrew.

He was said to be an abuse of alcoholic.

As a teenager, Weaver exhibited anti social behavior.

According to his sister, by the time he was twelve, he had physically and sexually abused at least one family member.

Weaver's own criminal career began early and escalated steadily.

In nineteen eighty one, a teenage relative reported him for rape, but ultimately prosecutors decided not to pursue charges because Weaver had enlisted in the U.

S.

Army Reserves, but he was discharged the following year for heavy drinking and dereliction of duty.

He married a woman named Maria Stout and welcomed a baby boy, Frances, in December of nineteen eighty two.

Three more children followed.

In nineteen eighty six, Weaver was arrested after he attacked the teenage daughters of a friend who were babysitting.

He hit one of the girls with a twelve pound block of concrete and was sentenced to three years in prison.

After his release, Weaver and his wife Maria relocated to Cambian, Oregon, where they operated a store.

There.

Maria gave birth to their fourth child, Mallory, in nineteen eighty nine, but even the facade of domestic normalcy couldn't contain Weaver's true nature.

In nineteen ninety three, Maria filed a restraining order against her husband, claiming he had threatened to shoot her and hit their children.

Two years later, Weaver's girlfriend, Christie Sloane filed a restraining order, claiming he beat her over the head with the frying pan while she was asleep and threatened to kill her and her family.

Her father, Mike, described Weaver as a domineering man who tried to control everything his daughter did.

Whenever she went to her parents' house, she could only stay a few minutes before Weaver demanded her home.

He was jailed for the incident, but Christie opted out of testifying against him.

The couple got back together and ultimately married in nineteen ninety six, before divorcing around three years later.

She said of him, he's a very mean and abusive person.

Now that he's behind bars, I'm not afraid to talk.

By the time Ward Weaver third was arrested for the rape of his son's girlfriend, he was no stranger to detective searching for Ashley and Miranda.

He had become a person of interest very early on in the investigation because the connections between him and the missing girls were impossible to ignore once she started looking.

His daughter, Mallory, had been friends with Ashley and Miranda.

The three girls attended the same school and the same dance class.

Ashley had stead over at Weaver's house on several occasions.

Five months before Ashley disappeared, she had accused Weaver of attempting to rape her at his home.

The incident was reported to police, but in a pattern that was becoming tragically familiar in Ashley's young life, they didn't formally file any charges against Weaver.

The timing was devastating.

Ashley's accusation came just as her biological father was about to face trial for sexually abusing her.

According to her aunt, Caroline Amos, Ashley's accusations against Weaver undermined her credibility in her father's case.

It made it look like Ashley was making up stories, Carolyn would later explain, so, once again, a system meant to protect Ashley instead failed her.

Naturally, Weaver became a person of interes in Ashley's disappearance.

Well not admisable in court.

He took a polygraph examination and failed spectacularly.

But rather than retreating into silence like most suspects might, Weaver did the opposite.

He maintained a high profile throughout the investigation.

He spoke with reporters, telling them openly that he was the lead suspect.

He admitted that he had failed a polygraph, but insisted he had nothing to do with the disappearances.

Most remarkably, he spoke about Ashley's allegations against him.

Speaker 1Actually has a habit.

She gets in trouble by someone should make accusations against that person.

And the first time that I actually had to come down on her about her mouth, she did just that.

You know, she made accusations that I in lest her.

I know, Astra ran away, you know, and the fact that the FBI has thrown both of these cases, you know, until someone took them both.

It's like, okay, fine, you know, I don't see it that way.

And I would really not like them think that someone took Miranda either girl.

Actually, but I well, I don't have anything to do with what's going.

Speaker 2On, he said to one reporter.

Basically, Ashley's problem was she just wanted someone to care about her.

She was looking for somebody steady who was going to take care of her and trade her like a young little girl.

He even claimed that Ashley had lived with him for five months, something her family denied.

We were described that he had treated Ashley like a daughter, paying for her clothing, feeding her, and taking her to California with the family the summer before.

His obsession with Ashley was so obvious that it had caused conflict with his then girlfriend, who felt that Ashley was receiving preferential treatment.

We've explained she felt that Ashley was trying to take over, as if a twelve year old girl could somehow manipulate an adult man, rather than the other way around.

We were also revealed telling details about his relationship with Ashley that in hindsight, painted a picture of calculated grooming.

He often drove her to school because she missed the school bus.

He explained, Ashley had this habit.

She really really didn't like to get up and catch the bus.

She took her time, waiting until the last minute to take a Shore, so I would end up having to take her to school.

But it wasn't just Ashley that Weaver knew intimately.

Miranda was in the same church youth group as his daughter.

He would drive Miranda to youth group meetings and school dance team practices, inserting himself into her life with the same calculated patients he had shootn with Ashley mirand had spent the night at Weaver's house on several occasions.

He was asked if he knew where they were by a reporter for Katu none.

Speaker 4I like to know her.

Speaker 1Both of mar like to see Miranda come home.

Masha, I'd igno where she's at, but honestly I didn't leave her there.

Speaker 2While under investigation, Weaver told his brother Rodney the police only suspected him because of their father's grizzly past.

Just a couple of days after Miranda vanished, Weaver had poured concrete over a hole in his backyard.

His daughter Mallory, had told the school guidance counselor she missed the church service for Ashley and Miranda because she needed to help her father dig a hole in the garden.

He claimed it was for a hot tub, but no hot tub ever emerged, just a suspicious concrete slab in the yard of a man whose daughter's friends kept disappearing.

Soon after, neighbors noticed him packing up his belongings, claiming he planned to move from the house.

And now with the Weaver behind bars on charge of first degree rape, detectives finally had the opening they needed.

Detectives obtained to search warrant for Ward Weaver's home on the twenty third of August two thousand and three.

They were focusing specifically on the yard, on that concrete slab that was supposed to have been for a hot tub that never materialized.

The concrete slab itself had become an accusation.

One of Ashley's relatives had taped a sign to the surface that simply read dig me up.

Before excavation, detectives methodically searched the rest of the yard.

First, there was a storage shed towards the back of the property.

They creaked open the door and saw a microwave oven box inside with the remains of Miranda Goddess, the girl who had dreamed of modeling, who had complained about Ashley getting all of the attention, who had made the haunting prediction about getting kidnapped.

She'd been there all along.

Then they excavated the concrete slab.

Underneath was a fifty five gallon barrel that had become Ashley Pond's tomb.

Her body had been mummified, and there was evidence she had been frozen at some stage.

A white rope had been wrapped around her neck and connected to her wrists and hands.

Both girls had been wrapped in plastic shading that came from Weaver's employer Manufactures Tool Service.

Weaver's fingerprints were found on the tape that was used to seal the cardboard box containing Miranda's body.

Ward Weaver, the third was indicted on charges of aggravated murder, rape, attempted rape, sexual abuse, and abuse of a corpse.

The prosecution announced that they were seeking the death penalty.

In the wake of the discovery, the true scope of institutional failure began to emerge.

Weaver's ex wife, Christie, revealed that she had told detectives five months earlier that they should dig beneath the concrete in the yard.

She had also told them about weaver Ver's family history, about how Weaver's father had buried his victim in the yard and then filled it up with concrete.

Yet somehow this crucial information had been ignored or forgotten while Ashley and Miranda lay decomposing mere yards where investigators walked their search dogs.

The community was stunned that Ashley and Miranda had been right there in the neighborhood all along.

Miranda's aunt, Terry Duffrey, captured the anguish that everyone felt when she said they came in and out of that driveway a hundred times and they were right there, I mean right there, and we couldn't do anything.

On the thirtieth of August, Oregon City High School opened their doors for thousands of mourners in tribute to Ashley and Miranda Kent.

Swatman addressed the crowd and said, we gathered today as a community to mourn their loss and to honor their young lives.

The town hadn't seen a homicide since nineteen ninety three, and thousands of people came out to pay their respect.

But beyond the grief and the flowers and the promises to never forget, a more uncomfortable reckoning was beginning.

Governor John Kizzieber announced that the state needed a fail safe system for investigating and following up on allegations of sexual abuse.

He promised they would examine whether the state had mishandled Ashley's sexual abuse allegations against Weaver.

That examination revealed a cascade of failures.

Ashley had told multiple people what Weaver had done to her, including a teacher and a prosecutor, had even been made aware.

In total, Child Protection Services received five separate calls reporting that Ashley had accused Weaver of sexually abusing her.

Five opportunities to save not just Ashley, but Miranda as well.

State officials claimed they had sent reports to the Sheriff's office, but the sheriff's office claimed they never received them.

State officials later acknowledged they hadn't followed up to see if their reports were received or acted upon.

As it turned out, they had sent the reports to the wrong place, a bureaucratic error that would cost two children their lives.

The truth was even worse than simple incompetence.

After Ashley reported Weaver's abuse, he had made her life hell.

He told her he was going to testify in her father's trial, claiming that her rapist father was a good man and accusing Ashley of lying in court.

Her mandor at school, Linde Verden, witnessed Ashley's terror and recalled there was no doubt she was terrified.

Speaker 4Linda Ward didn't rape me.

He tried to rape me.

I know the difference.

Then she chilled me to the bone by saying quietly, usually when I spent the night over there, he only lies on top of me.

Speaker 2So Ashley was caught in a perfect storm of institut tuitional failure and personal manipulation, a system that ignored her cries for help, while her abuser threatened to destroy what little credibility she had left.

She was twelve years old, facing down two adult predators and a bureaucracy that seemed designed to protect everyone except the children it claimed to serve.

In the end, to child welfare agency workers were fired for how they handled Arshley's reports of sexual abuse.

They blamed an overwhelming workload in a final insult to Ashley's memory.

Both workers were eventually rehired.

In August of two thousand and three, Miranda's mother, Michelle, filed a one point five million dollar lawsuit against the Oregon Department of Human Services, claiming they had mishandled the abuse reports.

The next month, Ashley's mother, Laurie, lost Costaday of her three remaining children after a co cutler reported a case of abuse by neglect.

Lourie then filed a nine point seventy five million dollar federal lawsuit claiming police and child welfare officials had failed to protect Ashley from Weaver.

The lawsuits ultimately ended in a ten thousand dollars settlement.

Meanwhile, Ward Weaver the third was speaking with reporters from behind bars, spinning new lies even as the evidence of his guilt surrounded him, He claimed that a shadowy conspiracy of outlaw motorcycle gang members and drug dealers were actually responsible for the murders.

He said, I'm ninety nine percent sure I'm going to walk out of this place in mid September when my trial is over.

He spoke with the confidence of a man who had spent his entire life manipulating his way out of consequences.

He spoke with katu, did you kill.

Speaker 4Ashley find and ran again.

Speaker 2No, I did not.

Speaker 4So if you didn't.

Speaker 2Kill Ashley and Miranda, then how did they wind up in your backyards?

Speaker 1Public property?

Who knows that place has been public existence, those apartments and those kinds have been built.

People kick out the back fence and walk up through my backyard.

Speaker 2But reality was beginning to intrude on Weaver's delusions.

In January, he was taken to hospital after slashing his chest and wrists with a disposable razor.

The injuries were superficial, and he was back in jail within ours.

A few months later, a judge sent him to a state psychiatric hospital indefinitely, suspending the trial.

Judge Robert Herndon said Weaver suffered from severe depression that prevented him from cooperating in his own defense.

A psychiatrist for the defense had diagnosed him with narcissistic personality disorder and major depression, but a competing expert for the prosecution said that he was faking some of his symptoms.

Since January, Weaver had carved his daughter's name into his forearm, lacerated his chest, banged his head against a wall, and told doctors he believed he was in jail as punishment for spanking his daughters.

He also reported here voices.

In August, after spending four months under psychiatric evaluation, Weaver was found combetan to stand trial.

The tarade of mental illness had run its course, and it was time to face the consequences of what he had done to Ashleigh and Miranda, but a murder trial would never come.

On the twenty second of September two thousand and four, Ward Weaver the Third was escorted into the courtroom, his shoulders slumped and his voice barely audible as he pleaded guilty to the murders of Ashley Pond and Miranda Gaddis.

The charges kept coming, two counts of abuse of a corpse, three counts of sexual abuse, the rape of his son's girlfriend's teenage sister, and no contest played at ten more charges, including the rape of yet another friend of his daughter, seventeen counts.

In total, seventeen ways he had destroyed innocence.

The plea deal would spare him from death row, but Ward Weaver, the third, would never see freedom again.

He received two consecutive life sentences.

The plea had come after Weaver's daughter sent him a letter that simply begged, Daddy, make it stop.

His own child could no longer bear the weight of what he had become.

In the victim impact statemens, the mother's words cut through the courtroom like broken glass.

Michel Miranda's mother said, I ask you today, Ward, did she suffer?

What were her last words?

Laurie Ashley's mother said, part of my life died with her.

I ask you, why did you have to kill her?

Weaver offered no explanation for his crimes.

He remained silent about his motivations, leaving only the detective's theories to fill the void.

Ashley had made allegations against him, accusations that threaten to unravel his carefully constructed facade, so she had to disappear.

Miranda, they believed knew too much.

After Ashley vanished, Miranda had warned a friend never to stay overnight at Weaver's home.

She believed he had molested Ashleigh, that other girls were in danger.

In Weaver's twisted logic, her knowledge made her liability.

Judge Hendon then addressed him and said, you will leave here with your life to day, such as it may be, I see nothing but evil.

I believe every one probably shares the hope that there's a special place in hell for people like you.

Years pasted, Miranda's younger sister, Maria, was only eleven when the murder shattered her world.

She grew into a young woman that was haunted by questions.

When she was eighteened, she reached out to her sister's killer.

She needed answers.

In prison, Weaver finally spoke.

He admitted what everyone already knew.

He had killed them both.

Ashleygh he claimed because she he saw something Miranda, in a grotesque twist of justification, to protect her from a bad home life, he described strangling both the girls with his bare hands, moving their bodies to confuse the police dogs.

Mira even visited him, but the visit stopped abruptly when Weaver made one final chilling revelation.

If he hadn't been caught, she would have been next.

Even behind bars word Weaver the third remained a predator.

The Weaver name would make headlines once more.

In two thousand and four, Francis Weaver, the boy who had grown up in his father and grandfather's shadow, was charged with murder during a drug robbery gone wrong.

He in two accomplices, shot Edward Spangler in the face and shoulder and left him to die.

Three generations, three weaver Men, three murderers.

The apple it seemed truly didn't fall far from the tree, But then came a revelation that cast everything in a different, more disturbing light.

Francis wasn't actually Waver's biological son.

His mother admitted that his real father was either Richard, a deceased marine, or Christopher, a man in the navy.

The boy raised as a Weaver wasn't really a Waver at all, which raised the most chilling question of all.

Was evil inherited or was a tout?

In the case of the Waver family, Perhaps it didn't matter.

Francis had been raised in War's image, molded by his example, shaped by his twisted worldview.

Biology be damned, he had learned to be a monster from the Master himself.

Well that is it for this episode of Morbidology.

As always, thank you so much for listening, and I'd like to say a massive thank you to my new supporters up on Patreon, sav and Susan.

The link to Patreon is in the show notes.

If you'd like to join, I upload adfree and early release episodes behind the scenes, and I also sand out March along with a thank you card.

I also do monthly bonus episodes of Morbidology Plus that are on the regular podcast platforms, and you can get these on Apple subscriptions as well.

Remember to check us out at morebidology dot com for more information about this episode and to read some true crime articles.

Until next time, take care of yourselves, stay safe, and have an amazing week.