Episode Transcript

There is an old country proverb to the effect that tombstones never lie.

In an obscure spot in an old cemetery at Newton, Kansas, is a grave at the head of which stands a small marble slab bearing these words in memory of Bertha L.

Bothamley, beloved wife of Clement L.

Bothamley.

Contrary to the old saying, this tombstone lies.

But it is a lie that will be forgiven its author, because it was engraven in marble to cover the sin of a woman.

The rearing of this modest marble slab marked the close of one chapter in a tragedy that had its scenes laid bare in two continents, ran the whole scale of human emotions, and ended in murder.

It is seldom that an operative in the Secret Service of the United States is selected to unravel crimes other than those against the currency of the country.

My connection with the Bothomley case came about through a request made by James L.

Brooks, at the time chief of the Secret Service of the Federal Department of Justice.

John W.

Carr, secretary of the British Association of Kansas, had written to the British ambassador at Washington asking that he solicit the aid of this government and clearing up the murder of a countryman and securing the conviction of the murderer or murderers.

Chief Brooks assigned me to the work because the crime had been committed in territory with which I had become familiar in the constant search for counterfeiters.

It often happens that the man who makes the unraveling of crimes a profession is called upon to take a case long after the commission of the crime he is detailed to solve.

Such tasks are the most difficult in the detective's calling.

Time is the criminal's strongest protector.

This is illustrated almost daily in our criminal courts and prosecutions which fail to result in convictions at the first trial.

Before a second trial can be held, some witnesses die or disappear, the recollection of others loses its clearness, and various considerations in favor of the accused appear.

These same considerations work to the advantage of a criminal before the case gets to the courts.

This digression applies aptly to the strange case I'm about to relate.

Had the same efforts been made in the early part of a certain October, as were started in the latter part of the following January.

I am convinced that the closing scene of the story would have been laid at the scaffold had certain significant incidents in the domestic history of a man and his wife in a small Dakota hamlet, and carefully investigated several months before I was called upon to go over them.

I am certain they would have led to startling revelations that would have proved one murder and prevented another.

Briefly stated, the mystery before me was the murder of Clement L.

Bothamley, a good looking middle aged Englishman.

Wealth these riches were computed in the West at the time, and while on his way over the Arbuckle Trail from Kansas to Texas with twenty three hundred sheep, The Arbuckle Trail was one of those great highways of the Plains that then served the nomadic cowboy, sheep herder and immigrant as wagon road and railroad combined.

Its winding course from Caldwell, Kansas to Fort Reno, Indian Territory was dotted on either side with lonely graves unmarked and in most instances spelled phinis to one of life's tragedies in such a grave.

The body of Bothamley had been buried the same day he was found dead, his final resting place being near a small post known the gruesome appellation of Skeleton Ranch.

This border country was plagued by murderous Indians and white desperadoes, one as much to be feared by peaceful settlers as the other, and each willing to cut a throat or use the deadly six shooter at the slightest prospect of game.

Three months or more had elapsed between the murder of the Englishman and the time I was assigned to clearing up the case, and this made it necessary for me to secure all the data concerning the finding of the body and the incidents attending it secondhand.

Fortunately, a seventeen year old boy, Wesley Vetter by name, who had been in the employee of the murdered man, was in Wichita and disposed to tell an unvarnished tale of the circumstances surrounding the death of his employer.

With this lad, I visited the scene of the murder, seventy miles from Caldwell.

This visit resulted in nothing except the fixing in my mind of the events as related by that to reduce the statements of his Kansas friends to a connected history.

Clement L.

Bothomley arrived in Florence, Kansas, some months before the murder, in company with a stately handsome woman, whom he introduced as his wife.

While the appearance of two personages of such evident distinction and wealth at the frontier town would naturally excite unusual interest at any time, the advent of the Bothomleys was an uncommonly memorable event, owing to the fact that their luggage consisted of thirty one trunks, to say nothing of innumerable boxes and portmanteau.

Bothomley's manner was that of a lord, and his companion indicated plainly by her hauteur of manner that her new environment was far different from that to which she had been accustomed.

In his talks with Florence people, Bothomley was a native of London who, with his wife, was seeking a home in frontier America.

He talked of cattle and sheep raising as his intended vocation.

Attempts to learn more of him than he told in a business way were futile.

After two weeks He moved from Florence to Newton soon after, moving to a ranch of six hundred and forty acres several miles from town.

Two months after his arrival at Newton, his companion died in childbirth and was buried there.

As there was no reason to doubt the truth of his claim that the woman was his wife, she was buried as such, and he assumed custody of her personal effects, including a three thousand dollars pair of diamond bracelets and other jewelry in wearing apparel amounting to much more in value.

Despite the distance at which Bothamley always kept his neighbors and the reticence he practiced in regard to his personal affairs, there was a wave of sympathy for him.

At the death of his wife.

He retired to his ranch, went in for the raising of sheep, and in a measure, dropped from view.

Throughout that section of Kansas there were several of Bothomley's countrymen engaged in the same occupation he had taken up.

One of these was William H.

Phillips, who was made the administrator of Bothomley's estate after the murder, and who told me that Bothomley's connections in his native country were high.

Later, among his effects we found a uniform of an officer in his Yeoman Cavalry which had been his, together with other evidences of his former prominent position in England.

According to the story of Vetter, who was employed at the Bothomley Ranch, his master announced one day in the summer that he was going to Newton to meet his sister, who was coming out from England.

On his return, he was accompanied by a petite, brown haired, blue eyed young woman of about twenty five, whom he introduced to the men at the ranch as his sister, Bertha Bothamley.

The pair lived at the ranch house as brother and sister, and the current of affairs ran smoothly until Bothamley decided to move to Texas, where he claimed he had a brother.

Arrangements were quickly made for the trip.

The outfit consisted of two thousand, three hundred head of sheep, fore yoke of oxen, some horses, a buggy and a wagon boxed in with ceiling.

This wagon had been used by an itinerant, da Geratyper.

The house part was seven feet high and wide and ten feet long.

It was supposed to furnish shelter for Bothamley's sister and to protect the owner of the outfit from wet weather as he was suffering from rheumatism.

The start was made the latter part of August, with Vetter and another man, William Dodson, to help care for the sheep.

Little progress was made at first, as Bothamley was attacked with rheumatism and had to be taken back for treatment.

October found the outfit at Hackberry Creek on the Arbuckle Trail, the scene of the murder.

Vedder and Dodson seldom slept more than a hundred and twenty five feet from the car, the woman sleeping on a raised couch in the car, and Bothomley on a shakedown on the floor or in a covered buggy close by.

Early in the morning of October seventh, Dodson and Vedder, who contrary to their custom, had gone to sleep some distance from the car, were aroused by cries from the woman, who was rushing toward them.

Something awful has happened at the car, she cried.

She was much excited and dazed, complaining that something ailed her head.

Vedder immediately went back to the car, found the door shut and returned to the others without attempting to investigate.

The woman urged Dodson to go to the car.

He opened the door and saw Bothomley laying on the blankets on the floor dead.

A bullet hole under the right eye told the manner of his death.

When Dodson informed the woman that Bothomley was dead, she became his stericle and wept violently.

Dodson saddled a horse and rode several miles to the camp of a man named Collins.

Bothomley's body was prepared for burial, the funeral taking place the same day at Skeleton Ranch, with the woman, Dodson, vetter, and Collins in attendants.

The next morning, Dodson and the woman washed the bloodstains from the bedclothes.

After three days, during which bothomley supposed sister said she had written to England concerning the death of her brother, preparations were made to continue the journey to Texas.

Meanwhile, however, news of the finding of Bothomley's body had traveled over the thinly settled country and reached the ears of the Indian Police, the regularly constituted constabulary of the Indian Territory.

Just as the outfit was about to move on.

The woman and the two men were taken into custody by the Indian police and sent to the Wichitaal Jail pending an investigation of the murder.

All three stoutly protested their innocence.

There was no general belief that either of the men had any guilty knowledge of the crime, but many thought the woman had committed the murder.

This remained to be proved or disproved, eliminating the possible guilt of the murdered man's supposed sister.

The most tenable theory of the affair was suicide.

This was the belief held by those who did not think the little, mild mannered woman guilty.

Steps were immediately taken to learn Bothomley's history, and this investigation was not without results.

Through different agencies, it was first found that Bothomley had deserted his wife and two children in London, and second that the woman with whom when he first came to Kansas was not his wife but a missus Harriet Miller, an englishwoman of wealth and position, who had deserted her husband in London in order to flee with Bothamley to a country where they could continue their guilty love affair without the ostracism and punishment with which they would have met in their native land.

They burned all their bridges behind them and started a new life in a spot where it was not customary to pride too deeply into the affairs of one's neighbors.

Then death took a hand thousands of miles from the home she had deserted for love of another woman's husband.

Missus Miller died and was buried under the name of a man for whom she had sacrificed all.

Her death was followed by a season of physical and mental suffering on the part of Bothomley, and this fact was one of the strongest arguments produced by the advocates of the suicide theory.

It was entirely reasonable to suppose that a man of Bothomley's evident refinement, after deserting his family under the stress of a mad infatuation for the wife of another man, should suffer a mental wrench at the death of his enamorata that might unbalance his mind and drive him to suicide in the solitude of a frontier trail.

This was an easily spun theory, and one that appealed strongly to the sentimentalists.

Personally, I do not believe that the Englishman had sent a bullet through his own brain.

I believe the records of this crime will bear me out in the general conclusion that the man who flings moral, legal and social obligations to the winds, as Bothomley had done when he eloped with Missus Miller, is seldom molded of such delicate clay as to blow his brains out when his companion and sin dies.

To follow the course that Bothomley had followed in England, a man must be essentially selfish, and selfishness of this kind does not beget self destruction.

To my mind, it was more probable that Bothomley had formed another laison than that he had destroyed himself, on account of the tragic ending of the first suicide.

Under these circumstances would have been the natural refuge of a woman, not of a man.

An additional support of my belief that Bothomley had been murdered, there were several corroborative physical circumstances.

One of the most convincing of these was the fact well established by science that the human animal instinctively shuns the pointing of a pistol to the eye when about to take his own life.

The bullet had entered Bothomley's face just under the right eye.

Scientists assert that there is not a single record of suicide by shooting in which the weapon has been aimed at the eye, and they go so far as to claim that such a course would be impossible.

To press the muzzle of a weapon against the forehead or the temple, thus hiding it from the vision is common, to point the weapon at the eye is unheard of.

Another circumstance going to disprove suicide theory was the finding of a pistol, a self acting Colt's forty five caliber, by the side of the body, in such a position that it seemed impossible for it to have fallen there had the shot been fired by Bothomley himself.

And further, there were no powder marks, according to veteran Dodson, on the man's face when found.

But the murder, if it is such, could never be established, and the guilt of the murderer proved with theories.

The case was under the general supervision of the United States District Attorney J.

R.

Hollowell, but the local authorities had done about all that lay in their power.

Colonel Hollowell left me to my own devices in the work that followed, merely saying that the Department of Justice was very much desired to have the murderer punished.

Truth compels me to say that I saw but one promising path to travel, and that was an investigation of the career of the woman whom Bothomley had introduced as his sister, and with whom he was making the journey to Texas when he met his death.

From all I was able to learn of the dead Englishman, he was a man who was more likely to meet his death through entanglement with a woman than at the hands of Indians or desperadoes.

I had studied the probabilities of murder at the hands of the last two agencies and found them weak.

There was no evidence that an avenging hand had reached across the Atlantic to punish Bothamley for the ruin of two homes in Elizon and Force at the time of his death.

Therefore, I expected to find the evidence desired.

Speaker 2To avoid future commercial interruption, join us at the Safehouse www dot Patreon dot com.

Slash true crime historian Rent is just a buck a week, so you can enjoy ad free editions of over four hundred episodisode's exclusive content, access to the Boss, and whatever personal services you require.

Www dot patreon dot com.

Slash true crime Historian.

The past is present.

Speaker 1At Skeleton Ranch, there was a post office presided over by a woman.

From this source, it was learned that some little time before the death of Bothomley, his companion had mailed two letters.

The post is not overburdened at an office like Skeleton Ranch, and the postmistress had plenty of time to inspect addresses of incoming and outgoing mail.

In this case, she was also garrulous and of retentive memory.

From her I learned that one of the letters mailed by the supposed sister of Bothomley was a bulky one and a legal envelope and addressed to the Clerk of Harvey County.

This proved, on investigation to have been a deed made by Sarah A.

Lah Laws, Spinster of Sedgwick County, Kansas, to Bertha L.

Bothamley of Harvey County, covering six hundred and forty acres of land in the latter county.

The consideration in the deed was given at twelve thousand, eight hundred dollars.

The description of the land and the deed coincided with the legal description of the ranch on which Bothomley had lived.

This discovery raised the question of the identity of Sarah a Laws.

Diligent inquiry failed to reveal such a woman, and had she lived in the county claimed it was unlikely that she could not be located.

The identity of the Laws woman therefore became a problem.

The fact that a deed to the Bothomley ranch, however, had been forwarded for record by Bothomley's woman companion, invested that person with even greater interest.

The discovery of her real identity was not a matter calling for any great effort.

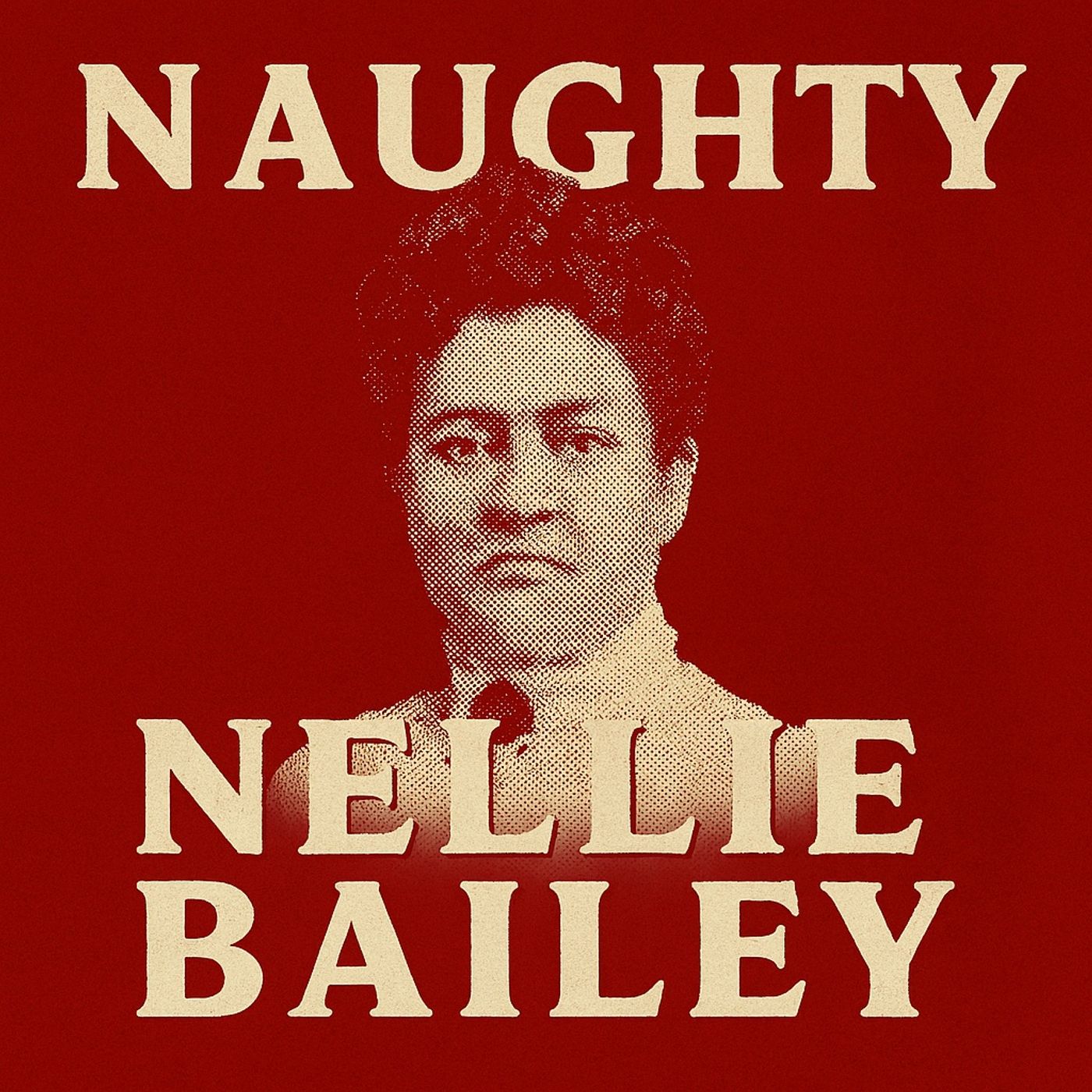

While at the Bothomley ranch, where she had passed as his sister, she had been identified as missus Nellie Bailey, the daughter of a Kansas rancher and carpenter named G.

F.

Benthaeson.

The whereabouts of her husband was unknown.

For the remarkable reason that will appear later, important chapters in her life were not known to her acquaintances in Kansas.

At this time, the circumstantial case against her seemed to be growing stronger.

In fiction.

The shrewd detective would have gathered a number of incriminating circumstances, grouped them into a narrative, which he would have recited to the suspect, who, thereupon, as a tribute to the skill of the detective, would have broken down and tearfully confessed the crime.

Had intelligent work been done immediately after the finding of Bothomley's body, some such method might have been used with the results desired.

But I doubt the effect of the deduction and accusation method on Nellie Bailey.

At every intimation of her guilt, she looked you squarely with the bluest of blue eyes and protested innocence in a way that left the man who was firmly convinced of her guilt in doubt innocent or guilty.

Nature had given her a nervous system on which threats, insinuations, or other attempts to pierce her composure had not the faintest effect.

I believe she would have gone to the gallows had fate so decreed, with the same air of injured innocence that she maintained since the Indian police had taken her into custody.

Because she was the logical person to have guilty knowledge of the crime.

She was shrewd enough to know that the drear planes had furnished no witness to what had transpired in the little house on wheels on October seventh.

She knew that any case made against her must be purely circumstantial.

And she also knew that which I did not realize at the time, that in a country where women are few, a pretty woman, even if she be bad, is practically immune for the days of circumstantial evidence in a criminal trial.

Therefore, she stood pat in her innocence or guilt, placing it squarely up to the government to make its case.

Inquiry into the county in which she had lived developed several interesting and suggestive facts concerning her.

She was an expert markswoman with a revolver and a daring equestrienne.

She rode astride, shooting with accuracy at wolves and other game.

From the saddle, she usually carried a revolver slung to a cartridge belt buckled around her waist.

Small of stature, exuberant of health, daring in spirit.

Clad in short skirts and sombrero, she was a figure not soon forgotten by those who had seen her.

Despite her mannishness in the saddle and with the pistol, she had played a part in numerous love affairs.

For it must be remembered that on the frontier a woman in a sombrero is not a rarity, and one that can rope a pony or shoot straight is not classed as masculine.

These were traits of the planes desirable, rather than otherwise, even in a pretty woman.

From the time Nellie Benthesen had gone into long skirts, she had associated principally with men among whom she was a favorite, and neighborhood gossip recorded numerous love affairs of more or less earnestness.

In all, she had earned the reputation of being fickle, quick conforming attachments, and equally quick in dismissing them.

These love affairs had culminated in her marriage to Shannon Bailey, a young lawyer, good looking of some means, giving promise of rapid advancement in his profession, and intensely in love with the high spirited, hoyendish Nelly.

During the courtship, Bailey had been the victim of at least one of that numerous class of individuals who delight in carrying gossip to the person most interested in this case.

One of these officious chatterboxes whispered things to Bailey about his fiancee that adoring lovers do not like to hear.

These whisperings had the usual effect.

Instead of breaking the attachment, it strengthened it.

But at the same time it planted seeds of distrust that later bore their fruit in a more gruesome way.

Bailey promptly married the girl, but decided that they could be happier were she taken away from the scene of her girlish attachments.

The Pacific coast was decided upon, and to that coast they went.

They spent two months in California, Oregon, and Washington.

Over this trail.

I did not follow them.

They returned to Kansas, settling to imporarily at Clinton.

Here, the fickle bride, almost immediately on their arrival fell in love with the telegraph operator, and Bailey noted the attachment.

There was a scene.

Bailey shot at his wife's new admirer, missed him, and then whisked his bride away to Dakota.

They first went to Huron, intending to settle there, and took rooms at the right house.

In a few days, missus, Bailey plunged into another flirtation as furious as the first.

Another scene resulted, ending in separation.

Bailey took quarters away from the hotel and his bride remained at the right house.

Several days later, Bailey and his wife again became reconciled.

She evidently had the power to throw him into the most violent fits of jealous rage, and then by pretense of repentance and other women's wiles, to bring him to her feet again.

Right after this second reconciliation, the pair moved to to Smet, a mere hamlet at that time containing only sixteen families.

The country was new and was being developed by the railroad that had just built a line through it.

Bailey believed that the village had a promising future and announced his intention to settle there and go into the real estate and loan business.

In his travels he carried with him several thousand dollars, and soon after arriving at De Smet, he deposited the money at the Bank of Kingsbury County, conducted by Thomas H.

Ruth.

The Baileys had rented a two story building that had been used as a shoe store with living rooms above, bought furniture, and soon were, to all appearances comfortably settled.

The ground covered by the Baileys from the time they returned from the Pacific coast until they settled into smet was all carefully gone over by me.

It must be remembered that in these wanderings they had nearly been a year in advance of me, and I necessarily depended to a great extent on the gossip that they had left in their wake.

From this I sifted as carefully as I could the statements that I deemed worthy of credence.

At each place they had stopped.

There were plenty of tales of jealous quarrels, always due as nearly as I could judge, to the fickleness of the bride and her seeming wanton pleasure in keeping her husband in the throes of jealous rage.

The conclusion I drew was this, that here was the case of a woman who had married not from love, but because her suitor had been a desirable catch.

I was satisfied that she had no genuine affection for Bailey, but to the daughter of an obscure carpenter, an offer of marriage from a rising agreeable young lawyer of ample means was not to be treated lightly.

Thus I judged the woman on the facts as I had gathered them, and without prejudice or desire to work any injustice.

And here I wished to say that, in my many years of work in hunting down and securing evidence against criminals of all kinds, a career begun in eighteen fifty six, I have never been dishonest in trying to manufacture evidence any person suspected or accused.

I've never been dishonest in trying to manufacture evidence against any person suspected or accused.

And I've never formed premature notions of the guilt or innocence of a suspect, always reserving conclusions on this point until the facts gleaned forced such conclusions.

I am fully aware that many detectives of my personal acquaintance first assume the guilt of a suspect and then make the evidence fit their preconceived idea.

Even handed justice is due to the worst criminal if they are guilty.

Intelligent, honest, and persevering work on the part of the officers of the law will develop that fact if the evidence is in any way obtainable.

If not, I have always believed in the adage that it is better for nine guilty men to escape than for one innocent man to be punished.

So in the case of Nellie Bailey, I took the stories of her flirtatious wanderings for just what they were worth, as shedding light on the character of the woman, and for nothing more.

On April twenty fourth, the Baileies moved into their De Smet home.

For three days, Bailey was seen about town and good health and spirits, engaged in the petty affairs connected with the furnishing of his home.

So far as I could learn on my arrival at Dusmet several months later, he had not been seen by any of the neighbors.

After the twenty seventh of the same month.

He had bade no one goodbye, and none of the townspeople had seen him leave.

Missus Bailey went blithely about her daily household duties, and when questioned concerning the absence of her husband, explained that he had business interests in California and had been summoned thither by telegraph.

Of course, there was some gossip over the hasty and unseen departure of the lawyer, but it turned more on his having deserted his wife on account of her frivolity and freedom of action with other men than on anything more serious.

For two months, Missus Bailey lived in De Smet, and then she announced that her husband did not intend to return there, and that she intended to leave.

The newly bought furniture was sold at a sacrifice, and other preliminaries to her departure quickly arranged.

Elgia and Illinois was given as her destination, and later this was found to be the place to which she went.

Thus, the Baileies faded out of Dakota.

On my arrival at Du Smet, I went to the bank of Kingsbury I had sent in and assumed name, and while waiting to be admitted, a voice called out, hello, Terrell, is that you.

I found the speaker to be mister Ruth, who had served on a jury before which I had a counterfeinny case in Saint Paul.

There was no further chance for me to conceal my identity or my mission.

The Ruth brothers placed their services at my disposal.

From them, I ascertained that Bailey had deposited several thousand dollars in the bank when he first came to De Smet, and that he had withdrawn it soon afterward.

From the same source I learned of the arrival and departure of the Baileys, and out of the gossip that attended the disappearance of the lawyer.

The facts gathered up to that time touching the career of Nellie Bailey were such as to strengthen my rapidly forming opinion that the woman was capable of deeds more desperate than flirting.

Although nothing in itself more serious had been unearthed, it was not difficult to imagine, however, the lengths to which such a woman might go to free herself from the thralldom of marriage to a jealous husband, for whom I was convinced she bore no real affection.

Her husband's possession of several thousand dollars in cash, coupled with her inordinate love of feminine finery, rendered stronger any other motive she might have had for wishing her husband out of the way.

The withdrawal of his funds from the bank and his sudden disappearance from De Smet presented themselves to me as additional grounds for harboring the theory that had been forcing itself on me that Shannon Bailey had been murdered by his wife from the depths of his infatuation for his wayward wife.

I found it difficult to believe that he would voluntarily absent himself from her for two months while she claimed to have been in communication with him.

I could find no trace of any exchange of letters between them, a fact that still further strengthened my belief that if the facts could be obtained, they would tell a story of a peculiarly deliberate and atrocious crime.

At this juncture, a bit of information startling to me in view of the theory I held, was introduced into the investigation by mister Ruth a few days before my arrival in d Smet.

It seems there had been found, in an unfrequented place on the prairie three and a half miles from De Smet, the bones of a man.

All the parts had been heaped together without even pretense at burial.

The skeleton had been dismembered and the flesh scraped from the bones, but there was nothing in the heap of bones which might establish the identity of the victim by measurement.

It was found that they had been the bones of a man about the height of Shannon Bailey.

There all clues were lost.

It seemed to me that the most promising channel for investigation from this point was a search of the premises formerly occupied by the Baileys.

Ruth accompanied me in this search, and that no unjust suspicions should be given circulation concerning the former mistress of the house about the task.

Quietly, the house had of course been dismantled of the furnishings used by the lawyer and his wife on the first and second floors.

Nothing whatever was found that might, by any stretch of the imagination, lend color to my suspicions.

Armed with spades, we then descended to the cellar, carefully testing the condition of the dirt floor.

We again met with failure, but one spot remained unexplored, the small area under the wooden stairway that formed the cellar entrance.

As a last resort, I thrust a spade into the floor under the stairs.

It sank deep into the loose dirt.

Quickly we removed the top soil, and as we did so, the awful, sickening odor of decomposing flesh became almost overpowering.

At a depth of a little more than two feet, the spade struck a mass of flesh.

Although almost overcome, we completed the excavation to find a mass of flesh buried in quicklime.

Not a bone was there to be found in this sorry grave.

There was not the slightest doubt of the flesh being that of a human being, and the quantity indicated clearly that it had been stripped from the bones of a full grown man.

The action of the lime and decomposition had done their work well enough to obliterate opportunity for identification.

In the meantime, a woman in De Smet who had been found who had had a letter from Missus Bailey in which the latter said her husband had just spent some time with her in Elgin.

This indicated two things, First that Missus Bailey had really gone to Elgin, and second that she believed it expedient to keep alive in De Smet the belief that her husband was living.

Therefore, I went to Elgin.

Speaker 2Enjoy ad free listening at the safehouse.

Dubbadubbadubba dot Patreon dot com, slash true crime historian.

Speaker 1No difficulty was experienced in finding that missus Bailey had stopped with one aunt for two days, leaving to go to another aunt with whom she had spent six weeks.

It required some cautious inquiry, however, to develop the fact that Nellie Bailey had brought with her to Elgin her husband's jewelry, among it the watch formerly carried by him and bearing his name.

I reasoned that if Shannon Bailey had been alive, it was altogether improbable that his wife would be in possession of the watch, especially as she had a reliable timepiece of her own.

Her possession of other trinkets formerly used by her husband gave additional color to the theory that Bailey was dead.

Then this fact was learned.

The aunt with whom she was visiting had a daughter about Missus Bailey's age, and one day the two had gone fishing.

When Missus Bailey left the house, she took a package from the bosom of her dress and gave it to her aunt, with strict instructions to take good care of it.

Curiosity on the part of the aunt prompted her to examine the packet, which contained several thousand dollars in bills of large denomination in Elgin, missus Bailey said her husband was in California, and I could find no trace of his having been in Elgin, as his wife claimed in her letter to her friend and dismet.

In the course of missus Bailey's visit to Elgin, there were many minor events, all pointing in the same direction, but with which I shall not encumber this narrative.

Ever, restless, the woman went from Elgin to Waukeshaw, Wisconsin, where she at once became acquainted with Robert Reyes, the twenty eight year old son of the proprietor of the leading hotel of that place.

The young man apparently fell prey to the woman's wiles without even a pretense of resistance, and in a few days was secretly chained to the wheel of her chariot.

The sudden and ardent attachment between the two became a matter of general knowledge and comment, and the parents of the young man evinced the bitterest opposition to it, but without avail.

Young Reese announced that he was going to stage a play in which the fair Nelly was to assume the star role.

After leaving Dakota, Missus Bailey had traveled under her right name declaring in both Elgin and Waukeshaw that her husband was alive.

Her infectionion for young Reese, however, seemed to be as sincere an affair as it was in her nature to harbor, enough so at least to prompt her to take the initiative and entice her lover into marriage.

Reese, who was much the weaker character of the two, feebly protected against being made the instrument through which the crime of bigamy, as he supposed, was to be committed by his enamorata.

But his protests were silenced by her vehement and off repeated assurances that Shannon would never appear to bother them.

On this point, she was very positive.

It is not likely that Rhese had any conception of the full significance of these words.

Missus Bailey insisted on the marriage being kept secret until legal separation from Bailey could be brought about.

Reese finally agreed, and the marriage took place without further delay at Waukeshaw.

As at Elgin, Missus Bailey exhibited the watch formerly worn by her husband, Reese, among others, having seen it.

The marriage at Waukeshaw had placed the woman in this position.

If Bailey were alive, she was a bigamist, and if he were dead, she was undoubtedly his murderous.

Her vigorous assurances to Reese that there was no danger of Bailey ever bothering them had for me, of course, a gruesome meaning, strange as it may seem to the uninitiated in the ways of such as Nelly Bailey.

I finally believed her to be a woman who would commit the greater crime of murder rather than place herself in her husband's power by committing the lesser crime of bigamy.

At any rate, her positive statements to Reese that Bailey would never bother them was, in my opinion, an important link in a long chain of circumstantial evidence.

Almost immediately after our marriage, reel or Mock to Reese missus Bailey had to make a trip to Kansas to sell a farm she owned there and would come back to Reese with eighteen thousand dollars.

And in connection with this pretense, I succeeded in establishing a fact of the utmost importance that she had been receiving letters from Clement L.

Bothamley during her stay in Wisconsin.

It was not my good fortune to secure any of these letters, but the fact that such a correspondence had been carried on was well established.

Her statement to Reese that she was going to Kansas to sell a farm was clearly a so refuge to escape, unsuspected from the man whom she professed to love so deeply, to go after another admirer.

She left Waukeshaw, still protesting the liveliest affection for Reese, and went to Newton, Kansas, sending to her Wisconsin lover from several points en route messages of undying love.

Bothamley had evidently been advised as to the exact time of her arrival, for he met her at the train and later took her to his ranch under the name of Bertha Bothomley, his sister from her journeyings of thousands of miles subsequent to her marriage with Shannon Bailey.

There seemed to be nothing more obtainable in the form of evidence against Nelly Bailey or Nellie Reese than I have related.

Any additional evidence must be obtained in Kansas, near the scene of the Bothomley crime.

The sending by her from the Skeleton ranch of the Sarah A Laws ded to Bothomley ranch should prove a valuable bit of information if the mystery of the identity of Sarah Laws could be solved.

The key to this puzzle finally was found in Wichita.

Two days before Bothomley and the woman had started to Texas, they appeared at the office of a lawyer in that city and solicited his services for the drawing of a deed to the six hundred and forty acres of land in question.

To this lawyer, the woman was introduced by Bothomley as his wife, Bertha L.

Bothamley, and they desired to convey the ranch property to one Sarah A.

Laws.

The instrument was drawn, the fee paid, and the couple departed, leaving no suspicion that either was other than as represented in the transaction.

The grantee did not put in the appearance, but there was nothing in this circumstance to arouse suspicion.

Knowledge of this visit to the lawyer enabled me to see what the plan might have been.

Further investigation revealed the fact that within an hour from the time Bothomley in the woman had left the office where the deed was drawn in favor of Sarah Laws, they had visited the office of another lawyer and asked him to draw a deed to the same land, Sarah A.

Laws being the name given as the granteur, and Bertha L.

Bothomley as the name of the grantee.

In the office of this lawyer, Bothimley introduced the woman as Sarah A.

Laws.

This was the deed that was afterwards sent by the woman from Skeleton Ranch to the Clerk of Harvey County for record, the character of Sarah A.

Laws having been purely fictitious.

This was the most convincing circumstantial evidence developed, going to show that the flight to Texas had been planned weeks and possibly months prior to the start, and that Bothomley had fallen so completely under the spell of the woman that he had been induced by her to convey his ranch to her.

The roundabout method described being used for the purpose of forestalling the comment a direct conveyance undoubtedly would have caused.

With the facts here as related in my possession, I conferred with Colonel Halliwell and we took an inventory of the evidence in our possession.

Of its circumstantial character, there was, of course no doubt the outline of the facts that I've related was strengthened by a search of the personal effects belonging to Bothamley at the time of his death, and of the contents of the car in which he died.

In a box in the car, besides a large quantity of jewelry which had belonged to the woman with whom Bothomley had come to America, was found a bottle of morphine.

I tried to establish the identity of the purchaser of the drug, but was unsuccessful, for after locating the druggist who sold it, I found him unable to recollect a person who had bought it.

The facilities for the exhumation and examination of the boy on the frontier were not so much as to make an analysis of the Bothomley stomach feasible, and the part played by the drug and the death of the Englishman, if any, was left in doubt.

When we had finished taking stock of our evidence, Colonel Hollowell, known throughout Kansas as Prince how and I decided that we would go into court with a circumstantial case of great strength.

Personally, I was confident of being able to present such evidence as would convince any unprejudiced juror of the guilt of Nelly Bailey or Reese, the physical circumstances surrounding the death of Bothomley.

Had the accused been a man, would have gone far of themselves toward convicting.

These circumstances considered in connection with the history of Nelly Bailey from the time of her marriage, the disappearance of her husband, the finding of the human bones and flesh, her possession of his jewelry and money, her marriage to Reese, and her confidence that Bailey would never bother them.

The evident attempt on her part to secure title to Bothomley's ranch.

All these things, and many minor circumstances seemed to me to constitute a case of much merit from the legal viewpoint.

In this view, Colonel Hollowell agreed with me, the genial United States District Attorney, and I differed, however, on one material point, the chance of securing a conviction.

Remember Torrell, he said that it's a woman on trial, and a pretty woman.

The trial of this remarkable woman was one of the most memorable in the history of Kansas.

She had ample means and had retained able counsel.

Colonel Hollowell, in his capacity as the United States Attorney, represented the prosecution, as the crime had been committed in the Indian territory where there were no local courts.

The government's array of circumstantial evidence was marshaled before the jury, and with much skill enforced by Colonel Hollowell, and a display of correlated facts produced that would have caused an ordinary defendant to weaken.

But the little blue eyed woman remained as calm as the incriminating circumstances were piled up against her as she had been from the first.

Counsel for the defense made the best of what meager case they had, but when the evidence was all in there was a wide margin in favor of the prosecution.

After the summing up by the lawyers, Colonel Hollowell said to me, we are up against it.

Every man on that jury knows she is guilty, and not one of them will vote for conviction.

His knowledge of Western juries in cases where women were defendants was accurate.

After due deliberation, the jury filed into the room and submitted to the court its verdict not guilty.

Judge Foster, who heard the case, said after the trial that there was not the slightest doubt in his mind of the woman's guilt, but she was free.

Robert Rees had come to Kansas to attend the trial, and immediately after the verdict disappeared with the woman I believed to be his wife, and who was his lawful wife if the bones and flesh found in Dakota had been those of Shannon Bailey.

I found afterward that while the jurors almost unanimously expressed themselves as believing the prisoner guilty, they had applied to the case their sense of rough frontier justice, reasoning that Bothamley had been a man whose early advantages and intelligence should have led him into a different life, and that if he met death at the hands of one woman after he had led another to desert her home for him, besides deserting his own wife and children, he was meeting with no more punishment than he deserved as a man.

I have no quarrel with this reasoning.

As an officer of the law at the time, I felt much disappointment at seeing the hard work of months go for naught, especially as that hard work had developed what to my mind was a sound case.

So far as I have been able to learn, Shannon Bailey has never been heard of since the day he disappeared.

I have recently written to his brother, who formerly lived in Ohio, but received no answer.

I mistake my reputation that we found all that was mortal of him on the Dakota Plain and in the cellar of his former home in De smet