Episode Transcript

Welcome to Hidden Cults, the podcast that shines a light into the shadows.

Here we explore the strange, the secretive, and the spiritually seductive.

From fringe religions to doomsday prophets, from communes to corporate empires.

These are the movements that promised meaning and sometimes delivered something far more dangerous.

I'm your host, and in each episode, we uncover the true stories behind the world's most controversial cults, the leaders who led them, the followers who followed, and the echoes they left behind.

If you or someone you care about has been impacted by a cult, you're not alone.

There is help.

Whether you're still inside a cult or trying to process what you've been through, support is out there.

You can find organizations and hotlines in the description of this episode.

You deserve freedom, healing, and a life that's truly your own.

Reach out.

The first step is often the hardest, but it's also the most powerful.

If you'd like to share your story and experiences with a cult, you can email it to me and I will read it on a future Listener Stories episode.

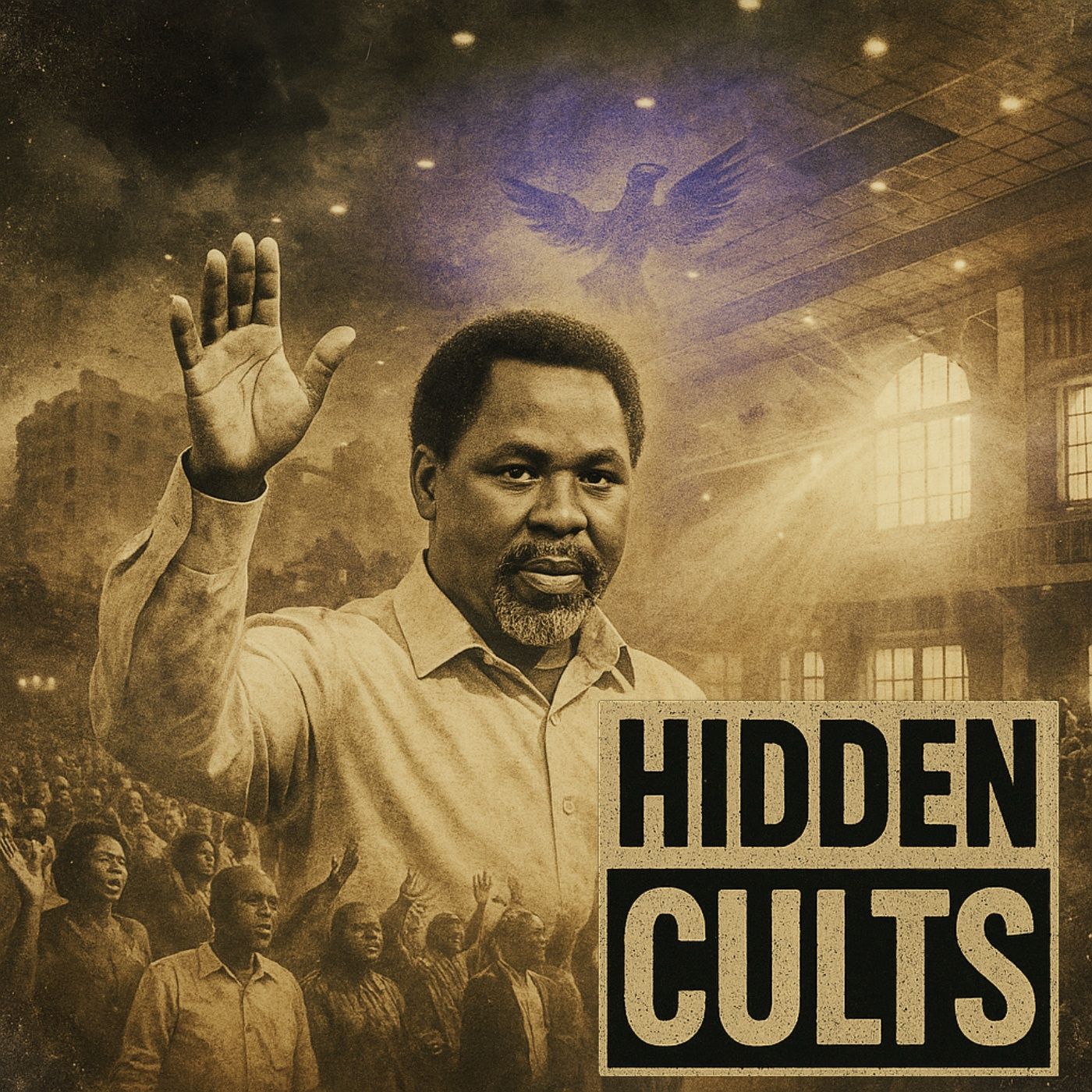

Your anonymity is guaranteed always today's episode, let's begin the Synagogue Church of All Nations, Part one, The Prophet of Legos.

In the humid, red soiled villages of Ondo State, Nigeria, a child was born in June nineteen sixty three who would grow to become one of the most influential and controversial religious figures in modern African history.

His name was Tematope Balagan Joshua, though the world would come to know him simply as TB.

Joshua, the self proclaimed Prophet of Nations.

From the beginning, Joshua's story was told in supernatural terms.

His mother, he would later claim, carried him in her womb for fifteen months.

At birth, a strange light reportedly surrounded the child.

His early followers took these tales as proof of destiny, evidence that he was marked by divine purpose.

From the start, TB.

Joshua's upbringing was far from miraculous in material terms.

He grew up in poverty in the small town of Rigidia Coco in southwestern Nigeria.

His father, a Muslim farmer, died when Joshua was still a child, leaving his mother to raise him alone.

The family struggled to survive, and Joshua's education ended early when they could no longer afford school fees.

Despite hardship, or perhaps because of it, the boy developed a reputation for unusual devotion.

Neighbors recalled him spending hours in prayer or retreating into the forest for solitude.

In interviews later in life, Joshua described himself as a boy of the bush, claiming that it was during these long moments of isolation that he first began hearing God's voice.

He suffered from illness throughout childhood, including a severe infection that nearly cost him his life.

He said the experience was transformative, that while on the brink of death, he saw visions of angels and heard a command to dedicate his life entirely to God.

In his early twenties, Joshua moved to Legos, Nigeria's commercial capital, in search of work.

The nineteen eighties were a turbulent time in Nigeria.

Military rule, economic collapse, and widespread unemployment had driven millions into uncertainty.

Legos was overflowing with migrants looking for hope in any form, and religion offered one of the few stable refuges.

Joshua began preaching informally in the city's poor neighborhoods, holding small gatherings under trees and in open courtyards.

His early messages were simple and emotional, centered on repentance, healing, and deliverance from evil spirits.

What set him apart was not theology, but presence.

He possessed an intense theatrical charisma that drew people in.

He prayed over the sick, laid hands on them, and declared them healed.

He claimed to see visions of people's pasts, their sins, and their futures.

Words spread quickly.

People brought relatives from far away, hoping for miracles, and in a city where hospitals were overcrowded and medicine was often out of reach, faith offered what science could not certainty.

By the late nineteen eighties, Joshua had gathered a small following who regarded him as a man chosen by God.

They began calling him the Prophet.

In nineteen eighty seven, in a makeshift structure in the Agodo Eggbay area of Lagos, Joshua founded what he called the Synagogue Church of All Nations sco on, the name he said came to him in a divine vision.

He claimed that God had shown him an image of the early Temple in Jerusalem and instructed him to rebuild it in spirit.

The early years were marked by humility and struggle.

Services were held in a patchwork building of corrugated iron and wood, often flooded during the rainy season.

Worshipers would faint, convulse, and claim to be freed from demons.

Joshua's intense prayers, delivered in a rhythmic mix of English and Yoruba, to possess their own strange power.

As crowds grew, so did the stories testimonies of miraculous healings spread by word of mouth.

The blind could see, the crippled could walk, the barren conceived.

Some of these accounts were unverifiable, but in a nation gripped by economic despair and social chaos, the power of hope itself was enough to fill the pews.

Soon, Joshua's modest shack of a church could no longer contain the faithful.

He began construction on a larger site in the Ekotin Eggbe area, a compound that would eventually grow into a massive religious complex with hotels, television studios, dormrmatories, and an arena capable of hosting tens of thousands.

By the early nineteen nineties TV, Joshua had become a household name in Legos.

His healing services drew crowds that spilled into the streets.

He touched foreheads, cast out demons, and spoke of divine visions.

He would call out strangers from the audience, describing intimate details of their lives, illnesses, family issues, as if reading them from the air.

To believers, this was divine knowledge.

To skeptics, it was performance.

But even the skeptics could not deny the magnetism of the man.

He combined the emotional pull of Pentecostal revivalism with a distinctly African flavor of mysticism and traditional spirituality.

Joshua framed his powers as a gift of mercy for a suffering world.

I am just an instrument, he would say.

The glory belongs to God.

Yet the more he spoke of humility, the more exalted his reputation became.

By the mid nineteen nineties, thousands traveled from across Nigeria and neighboring countries to seek healing at Scone.

The church's influence expanded beyond religion.

It began to shape culture, politics, and even health decisions in communities.

Where medicine was scarce, Joshua's prayers became an alternative form of treatment.

What set t be Joshua apart from other Pentecostal leaders of his era was his instinct for spectacle and his early understanding of media's power.

Even in the nineteen nineties, when Nigerian television was limited, Joshua filmed his services, editing them into highlight reels of miracles and deliverances.

These tapes circulated the spreading his fame far beyond Legos.

Villagers hundreds of miles away watched grainy footage of the prophet casting out demons or reviving the sick, and made pilgrimages to see him in person.

In a country that had grown weary of political corruption and economic stagnation, Joshua's brand of Christianity offered something thrilling, the possibility that God was still at work, performing signs and wonders in real time.

But Joshua's growing influence did not go unchallenged.

Nigeria's established Pentecostal leaders, particularly those belonging to the Pentecostal Fellowship of Nigeria PFN, viewed him with deep suspicion.

They accused him of using occult power, calling his miracles false and his theology heretical.

Joshua denied the accusations, but he never joined the PFN.

Instead, he turned their criticism into a narrative of persecution.

He portrayed himself as a prophet misunderstood by the religious elite, a theme that would later define his movement's identity.

This tension with the broader Christian community gave Scoon a sense of separation from the rest of Nigerian Christianity.

To his followers, that isolation was proof that Joshua was special, the true prophet in a sea of pretenders.

By the end of the nineteen nineties, TB.

Joshua was no longer just a preacher.

He was a national figure, a symbol of hope for millions, and the founder of one of the most powerful religious institutions in Africa.

But with fame came scrutiny, and with power came secrets.

The man who called himself the servant of the Living God was already building an empire where devotion would soon blur into control.

Part two, Miracles and Media.

By the early two thousands, Lagos had become the stage for one of the most extraordinary spectacles in modern Christianity.

Every week, thousands of pilgrims filled the narrow streets of Kotun Eggbay, waiting to enter the sprawling compound of the Synagogue Church of All Nations.

They came from across Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa, Zimbabwe, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

Some carried fohotographs of sick relatives.

Others arrived on crutches or stretchers, desperate for one last chance at healing.

At the center of it all stood TV Joshua, the man many now called the Prophet of our time.

He was no longer just a preacher from the slums of Legos.

He was a global phenomenon, a healer, a miracle worker, and, to his most devoted followers, a living conduit of divine power.

The Sunday services at scoone were a kind of performance that blurred the line between religion and drama.

The church's vast auditorium, known as the Arena of Liberty, was filled with cameras, bright lights, and volunteers guiding lines of worshippers toward the front.

Joshua would enter, quietly, dressed in his signature, short sleeved shirt and slacks, carrying a simple Bible.

When he began to preach, his tone shifted between calm conversation and explosive passion.

The crowd hung on every word.

Then, as the service reached its peak, he would move among the congregation, touching people's heads, praying, and shouting commands that seemed to summon something unseen.

Congregants screamed, fell to the floor, and convulsed.

Assistants rushed to catch them before they hit the ground.

Joshua declared that demons were leaving, that sickness was gone, that the power of Jesus was driving out every unclean spirit.

He would point to a person in the crowd and begin describing details of their life, illnesses, secret habits, family troubles, often with startling accuracy.

These moments became known as prophecies, and the congregation erupted in awe every time one proved true.

From the very beginning, Joshua understood that the true power of these events lay not only in the people who saw them in person, but in the millions who could watch them.

Later, that realization gave birth to his greatest tool of influence, immanual TV, founded in two thousand and six.

Immanual TV was Scoan's dedicated broadcast network.

Its slogan changing Lives, Changing Nations, Changing the World appeared at the start of every program.

The channel aired twenty four hours a day, broadcasting Joshua's sermons, miracle sessions, and deliverances across Africa, Europe, and eventually to satellite television networks worldwide.

The production was professional, sleek, and emotionally charged.

Cameras zoomed in on crying faces, trembling hands, and people rising from wheelchairs.

Dramatic music swelled as Joshua laid his hands on the sick.

Text overlays identified each case HIV positive, healed, cancer, gone, paralysis delivered.

Viewers watched in real time as men and women claim to feel strength returned to their limbs or pain vanish from their bodies.

The network quickly became one of the most watched religious channels in Africa.

In rural villages, it played in bars, salons, and bus stations.

Families gathered around televisions at night to witness what they believed were undeniable proofs of God's power.

A Manual TV also broadcast prophetic messages where Joshua would predict global events plane crashes, terrorist attacks, natural disasters weeks before they occurred.

When tragedy struck, the clips were re aired as evidence of his divine foresight.

To followers, it was miraculous.

It was manipulation through selective editing and vague predictions.

But even those who doubted could not ignore the influence of Joshua's televised ministry.

By the late two thousands, Scoon had become a pilgrimage destination.

The church built guesthouses to accommodate visitors flying in from all over the world.

Delegations arrived weekly, some led by local pastors who came to seek partnership or endorsement.

The air around the compound buzzed with energy, a mix of faith, commerce and media production.

Foreign visitors often filmed their own testimonies for Immanual TV.

After experiencing healing or deliverance, they were interviewed by staff who coached them on how to describe the miracle.

These recordings were then broadcast globally, reinforcing the message that Scoon was not just a church, it was the center of God's power on earth.

The economic impact was enormous.

Hotels taxi companies and local businesses thrived on the influx of religious tourists.

Nigerian officials, though wary of Joshua's unorthodox style, quietly tolerated his operations because of the money and visibility his church brought to the country.

But behind the scenes, Joshua's growing power made him untouchable.

His followers viewed him as a prophet beyond criticism.

His detractors saw him as a man who had learned to control faith itself, turning belief into spectacle and spectacle into wealth.

Miracles or manipulation the very thing that made Joshua famous.

His televised miracles also made him one of the most controversial figures in Africa.

Established Christian leaders accused him of fakery.

Medical professionals dismissed his healings as psychological manipulation.

Investigative journalists who tried to verify his claims found doors closed and witnesses reluctant to speak.

In twenty eleven, the BBC aired a documentary questioning the authenticity of Scohan's miracle claim, particularly healings related to HIV and AIDS.

The program featured families who said they had stopped taking medication after visiting the church only to see their loved ones die.

Scone denied responsibility, insisting that only those with true faith could sustain their healing.

Joshua's response to criticism followed a familiar pattern.

He portrayed himself as persecuted for speaking truth.

In sermons broadcast on a manual TV.

He reminded viewers that true prophets had always been hated by the world.

If they hated my master, he said, they will hate me too.

This framing only strengthened his follower's devotion.

For them, every accusation was proof that Joshua was genuine, because, as they saw it, the devil only attacked the righteous.

A manual TV became more than a broadcast channel.

It was the lifeblood of the movement.

Disciples who worked behind the scenes described grueling schedules, strict obedience, and a culture where failure to meet the prophet's expectations was treated as spiritual weakness.

The editing process was meticulous that didn't fit the narrative of victory.

Failed healings, inconsistencies, expressions of doubt were removed.

What remained was a world where miracles never failed, where every cry turned into a testimony, and where the prophet was always right.

This curated perfection created an impossible standard for both Joshua and his followers.

Within sco On, the pressure to maintain the image of supernatural success was enormous.

The prophet had to appear infallible, the miracles had to continue, and the cameras had to keep rolling.

By the early twenty tens, TB.

Joshua had become one of the most recognizable religious figures in Africa.

Presidents, athletes, and celebrities sought his blessings.

International media referred to him as the most powerful pastor in Nigeria.

His church was estimated to attract hundreds of thousands of visitors every year, generating millions in tourism revenue.

But with that fame came a quiet fear among those closest to him.

Disciples whispered about exhaustion, emotional manipulation, and the constant demand for loyalty.

Many had given up their families and careers to serve him full time, believing they were helping spread God's word to the outside world.

Skohen looked like a success story, a modern miracle factory run by a humble servant of God, but inside its walls, control, secrecy and image management were tightening their grip.

The man who had once stood barefoot under a tree to preach healing was now surrounded by cameras, security guards, and a carefully constructed mythology.

Every miracle was captured, edited and broadcast to millions.

Every doubt was buried beneath the weight of faith.

The profit of Legos had become a global brand, and as his fame spread across continents, so did the rumors of manipulation, fear, and the suffering hidden behind the glow of immanual TV Part three, The Megachurch Empire.

By the early twenty tens, the Synagogue Church of All Nations had become more than a place of worship.

It was a destination, a spiritual city state within Legos, guarded by armed security, pulsing with media crews, and governed by the will of one man.

For pilgrims who traveled there, Scohen was not simply a church, but a living miracle for the Nigerian economy.

It was a gold mine for critics.

It was the clearest sign yet that TV Joshua had turned faith into empire.

On any given weekend.

The roads around Ekotunegbe were a gridlocked sea of buses and taxis packed with visitors from across Africa and beyond.

Some came from neighboring Ghana and Cameroon, others from as far away as Mexico, South Korea, or the United States.

They carried bottled water, prayer cloths, and photographs of sick loved ones.

Many had saved for years to make the journey.

They called it a spiritual pilgrimage, and Scoon treated it as such.

Upon arrival, pilgrims were directed through tight security into a vast complex that stretched over several city blocks, marble floors, polished columns, fountains, and banners bearing Joshua's image.

There was an air of both all and order.

Everything from the seating arrangements to the prayer lines was controlled with military precision.

Visitors were housed in guest lodges operated by the church and charged fees for accommodations and faith packages.

Officially these were donations, but in practice they functioned as revenue streams.

Even outside the church, local businesses flourished hotels, restaurants, taxi drivers, ambers, and markets all depended on Scone's constant flow of international visitors.

A twenty eleven report by Nigeria's Tourism Board estimated that Scone generated tens of millions of dollars annually for legos.

The church had become one of the city's most profitable industries.

At the heart of the complex stood Scone's massive auditorium, a building known to followers as the Arena of Liberty.

It could hold thousands of worshippers and featured large projection screens that broadcast live miracles to those who could not get close enough to the stage.

Services began before dawn and sometimes lasted until nightfall.

The atmosphere blended revival, theater and war.

There were chants, songs, and spontaneous cries.

Joshua's image appeared on every screen, his voice amplified through towering speakers, assistance in matching uniforms.

Escorted the sick forward, people in wheelchairs, children with birth defects, the elderly carried by relatives.

Joshua moved among them with deliberate calm, touching heads, whispering prayers, or commanding sickness to leave.

Every act was filmed by a manual TV's production team capturing what would later become the network's global highlight reels, edited, scored and broadcast to millions.

In between healing sessions, Joshua preached about faith, charity, and obedience.

He warned of sin, of pride, of doubting God's servant.

Each sermon reinforced his central role in the story of Salvation.

Inside Scone TV, Joshua's word carried absolute authority.

He was not addressed as pastor or reverend, but as prophet, a title that placed him above human accountability.

To followers, he was the mouthpiece of God, capable of seeing the invisible and predicting the future.

To question him was to question God himself.

Members of his inner circle, known as disciples, lived within the church compound and adhered to a strict code of discipline.

They rose early for prayer, attended long services, and worked grueling shifts, editing videos, guiding visitors, or assisting with miracles.

Personal freedom was minimal.

Romantic relationships, family visits, and independent decision making were discouraged or forbidden.

Joshua controlled every aspect of their lives, where they slept, what they ate, how they spoke.

He was father, teacher, and master.

Some disciples later described the experience as spiritual imprisonment disguised as devotion.

Over time, Joshua's image became inseparable from Skohan's identity.

His face adorned walls, banners, and calendars.

Immanual TV broadcast montages of his humanitarian work, feeding the poor, helping disaster victims, donating to hospitals.

Every act of charity was framed as a gift from the prophet.

Even the church's architecture reinforced his legacy.

Sculptures and murals depicted scenes from his ministry, him casting out demons, healing the blind, or lifting the weak.

His office, positioned at the center of the complex, was treated as sacred ground.

Scohen's influence extended far beyond Nigeria.

Emmanuel TV established studios in Ghana, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, turning Joshua into an international celebrity.

Foreign politicians and celebrities made pilgrimages to Legos seeking blessings.

In twenty fourteen, Zimbabwe's then president Robert Mugabe sent representatives for prayer.

Joshua used this visibility to position himself as a spiritual diplomat.

He met quietly with heads of state advised military leaders and predicted elections.

His prophecies, though often vague, were replayed endlessly on television, creating an aura of political foresight.

During crises, from abola outbreaks to plane crashes, Joshua claimed divine knowledge of what was to come.

He called himself a watchman to the nations.

With this reputation came extraordinary power.

Nigerian politicians visited the church during campaigns hoping for endorsements.

Even those who distrusted him were careful not to speak against him in public.

Few wished to offend a man millions believed could see the future.

Behind the spectacle of miracles and the flow of donations lay a complex internal structure.

Scohen operated like a corporation and occult simultaneously.

Joshua oversaw every department personally media, logistics, security, healing lines, even the tailoring of uniforms.

All disciples reported directly to him.

Any complaint, even minor, could lead to public rebuke during meetings.

Those deemed disobedient were subjected to deliverance sessions, public rituals where they confess sins and begged forgiveness.

The hierarchy served one purpose to maintain Joshua's image as infallible.

Emmanual TV ensured that this image reached every corner of the world.

The prophet was presented as omnipresent, compassionate, and divinely empowered.

The man and the movement became indistinguishable, but the cracks were already visible.

A few former disciples began to speak anonymously to journalists, describing exhaustion, isolation, and mental abuse.

They said Joshua demanded total loyalty and punish those who questioned him.

The prophet, they claimed, lived in luxury while preaching humility.

Their stories were dismissed by the church as lies spread by the devil, but over time they painted a consistent picture, one of manipulation cloaked in spiritual language.

By twenty fifteen, Scone was one of the most visited religious sites in Africa.

Airlines offered special pilgrimage packages, hotels advertised profits weekends.

The church's annual income was estimated in the tens of millions.

Joshua appeared regularly on a manual TV, aging gracefully but still exuding quiet authority.

He spoke less about poverty and more about destiny.

He claimed to heal incurable diseases, predict wars, and rescue souls from demonic bondage followers.

This was proof that God had truly chosen Nigeria as the world's new spiritual center for outsiders.

It was the clearest example yet of religion as empire.

Faith turned into an industry, and at its center stood a man whose image was broadcast twenty four hours a day, who commanded obedience from thousands, and who seemed untouchable.

But behind the marble floors and polished cameras, pressure was building.

The same system that made TB.

Joshua a legend was beginning to trap him.

For every miracle televised, there were whispers of those that failed.

For every testimony of deliverance, there were claims of coercion.

The empire he built on faith and spectacle would soon face its reckoning, one that even the profit of Legos could not foresee.

Part four Shadows behind the Miracles.

For years, the Synagogue Church of All Nations projected an image of divine perfection.

Immanual TV beamed miracles to millions.

Governments treated the prophet with reverence, and thousands continued to flood into legos, believe they would find healing, salvation, or purpose.

But behind that image, behind the edited broadcasts and carefully staged testimonies, darker stories began to surface.

These stories came not from critics or outsiders, but from those who had lived within the prophet's inner circle, people who had prayed beside him, edited his videos, and believed every word he spoke until they could no longer bear the truth of what they had seen.

Within Scone's gleaming walls, there existed a second, invisible church, one that the cameras rarely showed.

It was the world of the disciples, the men and women who lived and worked full time for the profit.

They were the engine that powered the empire, editors, cleaners, prayer warriors, ushers, and production crew for Emmanual TV.

Most of them were young, often recruited from among devoted followers who wanted to serve God more deeply.

Once accepted, they were moved into dormitories inside the church compound and cut off from the outside world.

Family visits were discouraged or forbididden.

Communication with anyone beyond the church walls required permission.

The disciples worked long, exhausting hours, often from before dawn until after midnight.

Maintaining the daily operations of the church and its media network.

Sleep was scarce, privacy nonexistent.

Every part of life revolved around the prophet.

In interviews years later, former disciples described a system built on control and fear.

Joshua was treated as the voice of God.

Any questioning of his authority was labeled rebellion or demonic influence.

In fractions, even minor ones were punished through public humiliation or deliverance.

Forced confessions broadcast to others as examples of what happens when faith waivers.

Over time, more disturbing accounts began to emerge, stories of coercion, violence, and sexual misconduct hidden behind the prophet's public persona.

Several former female disciples alleged that Joshua used his spiritual authority to exploit and assault women within the church.

They described being summoned privately to his quarters, told that physical intimacy with him was part of divine anointing, and warned never to speak of it.

Some were allegedly threatened with spiritual damnation if they refused.

Others spoke of physical punishment, slaps, forced kneeling confinement for perceived disobedience.

A pattern of intimidation and secrecy kept these abuses hidden for years.

Victims were told that exposing the prophet would bring curses upon them or their families.

The church dismissed all allegations as lies spread by agents of darkness.

In official statements, Scone insisted that TV Joshua was a man of integrity under constant spiritual attack from jealous rivals and unbelievers.

But the stories continued to surface, not in tabloids or rumors, but in detailed, consistent accounts from people who had no connection to one another.

On September twelfth, twenty fourteen, the public face of Scohan's perfection cracked.

That afternoon, a multi story guest house on the church compounds suddenly collapsed, trapping hundreds of foreign visitors who had come for healing and deliverance.

The building pancaked in seconds, dust filled the air, Screams echoed through the streets, and emergency responders rushed to the scene.

When the dust settled, more than one hundred and fifteen people were dead, most of them South African pilgrims.

It was one of the deadliest structural disasters in Nigeria's history, but what followed shocked observers.

Even more, Instead of cooperating with investigators, Skoan immediately deflected responsibility.

The church claimed that the collapse was the result of a mysterious aircraft seen flying over the building moments before the disaster, suggesting that the church had been targeted in a deliberate attack.

Emmanual TV quickly aired edited footage of a low flying plane and looped it repeatedly, reinforcing the claim of sabotage.

Joshua himself described the event as a test of faith and urged followers not to listen to enemies of the ministry.

Authorities, however, found no evidence of any aerial attack.

Structural engineers later determined that the building had been illegally constructed, with weak foundations and additional stories added without approval.

Despite repeated court summons, Joshua refused to appear in person.

Legal proceedings dragged on for years as the church fought to shift blame onto contractors and government officials.

Families of the victims, many of whom had flown in from South Africa, pleaded for accountability, but their cries went unanswered.

To his followers, Joshua's refusal to stand trial was proof of persecution.

To outsiders, it was evidence of how far his influence extended that even a disaster claiming more than a hundred lives could not shake his authority.

The guest House tragedy marked a turning point.

While the prophet's most devoted followers clung to his explanations, others began to drift away.

A handful of former disciples left Nigeria entirely, haunted by guilt and disillusionment.

But outside the church walls, the myth was cracking.

Journalists were investigating, governments were growing uneasy, and even some within the Pentecostal community were beginning to call him dangerous.

Behind the miracles, behind the lights and cameras, something rotten was festering, and as the years went on, it would grow harder for even his most loyal followers to ignore.

Part five, The death of a Prophet.

On June fifth, twenty twenty one, the news spread across legas like a tremor.

The man millions called the Prophet of our time was gone.

TB.

Joshua, founder of the Synagogue Church of All Nations, faith healer, television evangelist, and one of the most influential figures in modern African Christianity was reported dead at the age of fifty seven.

It was a Saturday evening, only hours after he had delivered what would become his final sermon.

The title of that day's message was hauntingly, time for everything, time to come here for prayer, and time to return home after the service.

The words felt profefant in hindsight.

Joshua collapsed shortly after the broadcast, taken to the church's private medical facility.

Within minutes, he was pronounced dead.

Shock and silence inside scone, Panic met disbelief.

For more than three decades, TB.

Joshua had been the church's heartbeat, its founder, its face, its voice.

No one had prepared for a world without him.

Emmanuel TV went dark for nearly twenty four hours.

No official statement, no footage, no message to followers.

For an organization known for its NonStop broadcast of miracles.

The silence spoke volumes.

When confirmation finally came, it was through a short post on the church's verified Facebook page open quote, God has taken his servant Prophet TB.

Joshua home as it should be by Divine will close quote.

Within hours, the post had been shared tens of thousands of times.

Across Nigeria, crowds gathered outside the church gates, many crying openly.

In South Africa, Ghana and the Caribbean, vigils formed spontaneously.

Airports saw Philgrim's booking last minute flights to legos, hoping to attend what they called the prophet's heavenly transition.

For followers, his death wasn't the end of a man.

It was the passing of a divine messenger.

But for those inside Scone, it marked the beginning of something else, entirely the power vacuum.

Joshua had left no clear successor.

For years, he had ruled the church through personal charisma and spiritual authority, not institutional structure.

Every decision flowed from him, from finances to sermons to a manual TV content.

Without him, Scone was leaderless, and leadership meant power.

Almost immediately, a struggle erupted between his widow, Evelyn Joshua, and the inner circle of disciples, who had managed day to day operations for years.

Evelyn, a quiet figure throughout her husband's ministry, had rarely appeared in public, though she occasionally joined him at events.

Joshua never presented her as a co leader to disciples she was the prophet's wife, not his equal.

But within days of his death, Evelyn moved to consolidate control.

She stepped before the cameras for the first time in years, addressing the congregation in a calm but firm tone.

Open quote.

God has promised us that he will not leave us or forsake us.

We must hold on to faith and continue the work close quote.

Behind the scenes, tensions were rising.

Senior disciples resisted her leadership, arguing that the church had always been run through divine revelation, not family inheritance.

Some accused her of trying to seize the mantle.

Others feared losing influence or the access to wealth and status that came with proximity to power.

Over the next several weeks, the battle for Scone's soul spilled into public view.

Rumors of secret meetings, loyalty, oaths, and internal purges spread through legos.

Church accounts were reportedly frozen amid disputes over ownership and succession.

Several senior disciples were locked out of the compound, accused of disobedience and corruption.

Evelyn Joshua announced that she had been chosen by God and by her late husband's spirit to continue his minis.

Her claim polarized followers.

Some embraced her as the rightful heir, calling her Mummy Goo General Overseer.

Others saw her as an outsider hijacking a prophetic legacy.

The once united ministry fractured into camps.

Some disciples left the church entirely.

Others tried to establish independent ministries, carrying fragments of Joshua's teachings with them.

Emmanuel TV, once a global media powerhouse, went offline amid legal and administrative turmoil.

For the first time in nearly two decades.

The airwaves were quiet.

On July ninth, twenty twenty one, The world watched as Scoene held a grand state style funeral for TV Joshua.

His body lay in a white and gold casket before the massive Arena of Liberty, surrounded by dignitaries, musicians and politicians.

Nigerian security forces lined the streets as thousands of mourners dressed in white filled the church grounds.

The service was broadcast live across Africa.

Songs of triumph and grief filled the air.

Many wept, openly, calling it the homecom of a general, but the event also highlighted the contradictions of Joshua's legacy.

Outside the gates, critics protested what they saw as glorification of a man accused of exploitation and abuse.

Inside, worshippers chanted that his spirit lived on.

The Nigerian government issued cautious condolences.

President Mohammadu Buhari described Joshua as a philanthropist and man of peace.

Officials praised his humanitarian work donations to disaster victims, education programs, medical aid, while sidestepping questions about his controversies.

For legos authorities, the prophet's death was both relief and risk.

He had been too powerful to control in life.

In death, the vacuum he left threatened to destabilize one of the country's largest religious followings.

In the months that followed, Evelyn Joshua formally assumed control of Scoen.

She reinstated immanual TV broadcasts, reopened the church to pilgrims, and promised a new era of transparency.

Her leadership style was calmer, less theatrical.

Gone were the public exorcisms and wild miracle displays.

Services became shorter, sermons more restrained, but beneath the surface, divisions lingered.

Several of Joshua's longtime disciples refused to return, choosing exile over allegiance.

Some accused Evelyn of rewriting history, downplaying the darker chapters of the prophet's ministry.

Others saw her as a stabilizing force, the only person capable of preventing total collapse.

Meanwhile, survivors and critics hoped her takeover would open the door for accountability.

They urged the church to address allegations of abuse, financial misconduct, and the unresolved twenty fourteen building collapse that still haunted the ministry's reputation.

So far, that reckoning has not come, even in death.

TB.

Joshua's influence endures.

His sermons still air on television, his image still decorates calendars and billboards, and his quotes circulate endlessly on social media to millions of followers.

He remains a saint, a man who healed the sick, fed the hungry, and defied persecution.

For others, he is a warning, a charismatic figure who blurred the line between faith and control.

In legos, the marble walls of Scoon still shine under the tropical sun.

Pilgrims still arrive from across the world, clutching photographs and prayer requests.

Inside, Evelyn Joshua presides quietly from the pulpit where her husband once commanded the crowds every breath, But the air has changed.

The voice that once echoed through the arena of liberty is gone.

What remains is his shadow, vast, unchallenged, and still shaping the faith of millions who believe that their prophet only went home early, not away.

Part six, Faith, Power and Aftermath.

When TB.

Joshua died in twenty twenty one, many assumed the empire he built would vanish with him.

Scone had been a ministry rooted not in structure but in personality, a one man religion sustained by the magnetism of its leader.

And yet, against expectations, the Synagogue Church of All Nations did not collapse.

Instead, it adapted a new prophet and all but named the leadership of Evelyn Joshua Scohane rebranded itself as a gentler, more disciplined version of its former self.

Gone were the chaotic exorcisms and violent deliverance scenes that once filled Immanuel TV.

The new sermons focused on prayer, humility and faith in hardship.

But the changes went deeper than tone.

The church's image, once tightly controlled by TB.

Joshua's stagecraft, now carried a sense of restraint.

Where her husband had performed miracles, Evelyn preached stability.

Where he had spoken with authority, she spoke with empathy.

To followers, the continuity offered comfort.

They saw her as the anointed successor, the one chosen to carry on his divine mission.

Scohane's official website began referring to her as the Servant Leader, mirroring the language once used for her husband.

Emmanual TV resumed broadcasts, this time with a new slogan, changing Lives, Changing Nations.

The camera still lingered on the same altar, the same gold plated pulpit, the same sea of worship.

In white robes.

It was as though nothing had changed, only the face behind the message.

Outside the walls of the Lagos Compound, however, the prophet's legacy remained fiercely contested.

To millions across Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

TB.

Joshua is still considered a saint.

His portrait hangs in homes and shops.

His words are quoted in WhatsApp devotionals.

His recorded healings are replayed as proof that God once walked among them.

But for former disciples and survivors, his image carries a very different meaning.

They see him as a manipulator who weaponized faith, who made people believe that suffering, submission, and silence were holy virtues.

Many of those who escaped the church have spent years trying to rebuild their lives.

Some suffer post traumatic stress from years of emotional and spiritual control.

Others have found it impossible to reconnect with their families, who still worship the man they fled from.

Their stories, once whispered in fear, have slowly begun to reach the public.

Independent journalists, survivors networks, and human rights groups continue to document allegations of psychological abuse, sexual coercion, and fraudulent healings.

Nigerian authorities have opened sporadic inquiries, but full accountability remains elusive.

Even in death, Joshua's power persists not just in the minds of believers, but in the fear he left behind.

The twenty fourteen Guesthouse collapse still casts a long shadow over scan legal proceedings in Nigeria dragon with no resolution.

The families of the victims, many from South Africa, have waited more than a decade for justice.

Joshua's death complicated everything.

The case became tangled in bureaucracy, stalled by disputes over who holds responsibility.

Now that the church's founder is gone, investigators allege obstruction and delay tactics.

For survivors, it feels like another form of betrayal, the powerful escaping judgment through time and influence.

Meanwhile, other governments, including South Africa, continue to monitor scoen's satellite branches.

In twenty twenty three, the South African Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Rights renewed its call for transparency, demanding that faith based organizations be held to stricter ethical standards.

But in Legos, the church carries on unbothered by controversy.

Services remain packed, donations steady, and emmanual.

TV's audience counts in the millions.

To those inside, this persistence is divine proof that the prophet's anointing lives on to outsiders.

Its evidence of how charisma can outlive the man who wielded it.

Few religious movements have blurred the line between faith and performance as completely as go on bodies, convulsing demons, shrieking miracles caught perfectly on camera.

His services were part revival, part reality television, and yet for those who believed they were sacred moments, tangible encounters with the supernatural.

In that fusion of media and religion lies Joshua's most enduring legacy.

He turned televangelism into a form of national theater.

Every healing was a narrative arc, every prophecy a script of redemption.

The prophet didn't just command attention, he directed it, transforming worship into something cinematic.

Even now, a manual TV continues to recycle these moments, replaying the glory days of the prophet's reign.

For new followers, the distinction between past and present blurs.

TB.

Joshua has become both history and myth, a spirit whose sermons can still fill an arena from beyond the grave.

In the end, Scoene's story is not just about a preacher or a church.

It's about the psychology of belief itself, how ordinary people can surrender autonomy when faith is fused with fear, and how charisma can sanctify control.

TB.

Joshua built more than a congregation.

He built a reality where doubtless sin and obedience with salvation.

The tools were ancient fasting, prayer, confession, but the method was modern broadcast.

Faith isolate, descent and drown truth.

For those still inside scone, he remains a vessel of God's power.

For those who is escaped, he is a symbol of what happens when worship becomes dependency.

Both realities coexist, one in the pulpits glow, the other in the shadows behind it.

Today, the Synagogue Church of All Nations remains one of the most visited religious sites in Africa.

The arena of Liberty, capable of holding thousands, still fills every Sunday.

Pilgrims still travel from across the world to touch the marble floors, to pray where the prophet once stood.

But no sermon, no prayer, and no amount of gold on the altar can erase the contradictions that built it all, the mix of hope and harm, healing and exploitation, devotion and deceit.

The Prophet of Legos is gone, but his shadow lingers not only over the church he built, but over every soul that believed the miracles were worth the price of silence.

And so the story of the Synagogue Church of All Nations ends, where so many stories of faith and power due with lessons unlearned, wounds unhealed, and followers still searching for meaning in the wake of a man who called himself a servant of God.

Next episode.

The Love Family, a nineteen seventies Seattle based commune led by Paul Erdman known as Love Israel, a movement born from hippie idealism and Christian mysticism that crumbled under the weight of money, power and control.

That's next time.