Episode Transcript

Welcome to Hidden Cults, the podcast that shines a light into the shadows.

Here we explore the strange, the secretive, and the spiritually seductive.

From fringe religions to doomsday prophets, from communes to corporate empires.

These are the movements that promised meaning and sometimes delivered something far more dangerous.

I'm your host, and in each episode, we uncover the true stories behind the world's most controversial cults, the leaders who led them, the followers who followed, and the echoes they left behind.

If you or someone you care about has been impacted by a cult, you're not alone.

There is help.

Whether you're still inside a cult or trying to process what you've been through, support is out there.

You can find organizations and hotlines in the description of this episode.

You deserve freedom, healing, and a life that's truly your own.

Reach out.

The first step is often the hardest, but it's also the most powerful.

If you'd like to share your story and experiences with a cult, you can email it to me and I will read it on a future Listener Stories episode.

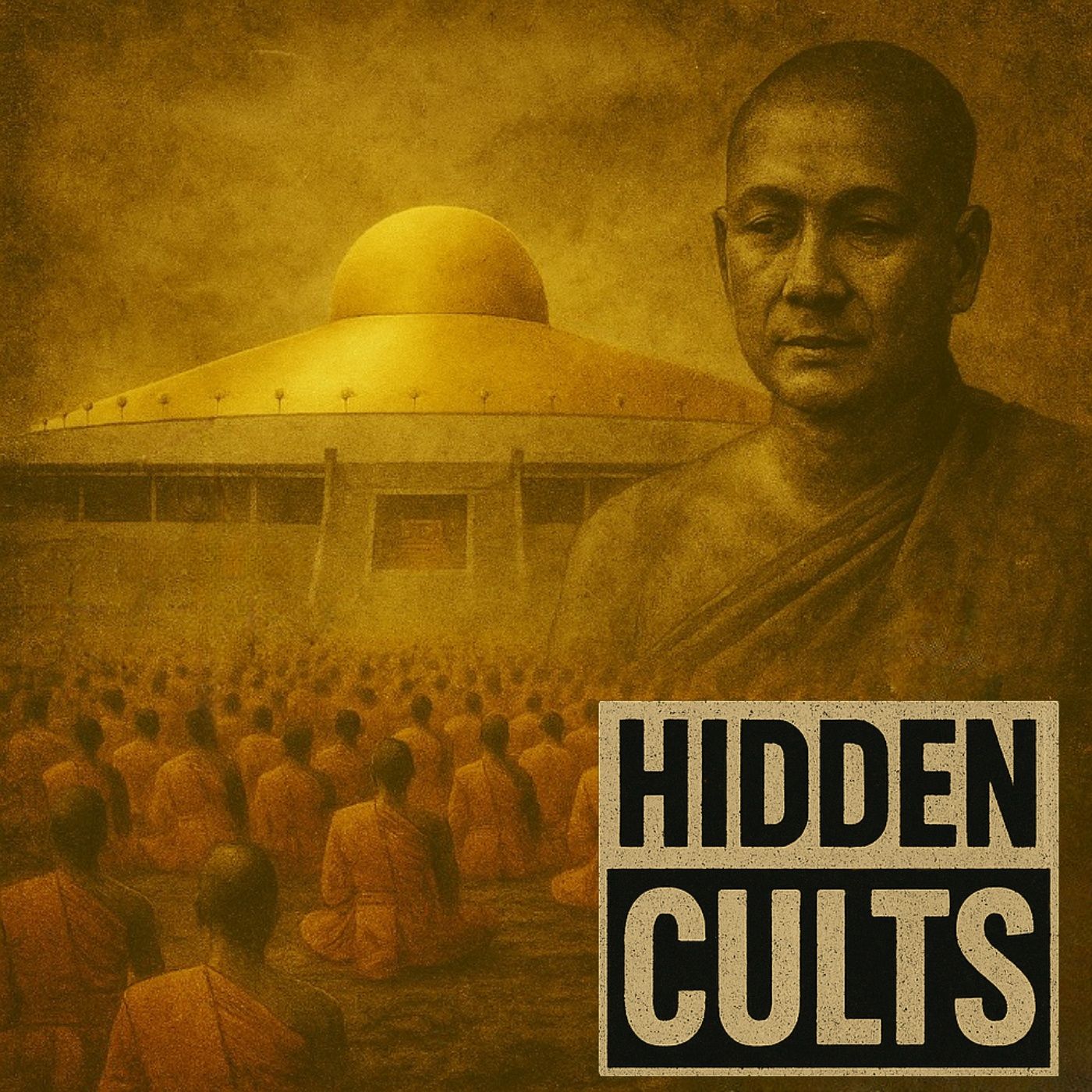

Your anonymity is guaranteed always today's episode, let's begin Watfrau Damakaia Part one, The Beginnings of Damakaia.

In the story of Watfra Damakaia, a sprawling golden temple complex that now stands as one of the largest religious sites in the world, it is easy to get lost in the scale, the domes that stretch like futuristic suns, the thousands of orange robe monks gathered in symmetry the satellite centers around the globe, but its origins were far humbler.

At the center was a woman whose beginnings could not have been more different from the gleaming empire.

She helped inspire Chandra Knokiung, born in nineteen o nine into rural poverty, who would rise to become one of the most revered Buddhist nuns in modern Thailand.

Her journey and her partnership with a young monk named Fra Damachaio later Luong Por Damajayo, gave birth to a movement that would shape Thai Buddhism and spark decades of controversy.

Chandra was born in Nakon Patan Province, west of Bangkok into a poor farming family.

She had little formal education, a fact that would remain with her throughout her life, and worked from a young age in the rice fields.

Thailand in the early twentieth century was still deeply agrarian, and opportunities for poor rural women were few.

Yet, even without schooling, Chandra developed a reputation for sharpness and spiritual curiosity.

Family members recalled that she often asked questions about karma, rebirth, and meditation, displaying a seriousness unusual for her age.

As a young woman, Chandra married and had children, but tragedy struck early.

She lost several children in infancy and her marriage faltered.

Widowed by her mid thirties, she began moving toward a religious life.

By the nineteen thirties, she had become known for her devotion to meditation, particularly the Damakaiah meditation method, a form of practice developed earlier in the century by the monk from moncolthep Muni of Wat Paknam Basicharone in Bangkok.

Chandra traveled frequently to Watpacnam, where she became a lay disciple under the guidance of senior monks.

Though she could not read or write, she absorbed teachings orally, relying on memory, devotion, and sheer determination.

It was at Watpacnam that Chandra began to earn respect as a meditation teacher in her own right.

Despite her lack of education, she was said to have an uncanny ability to guide others in meditation, especially in leading them toward visions of inner light described in the Damakaya tradition.

Followers considered her a living example of how deep practice, rather than scholastic knowledge, could bring wisdom.

She became known as Unyai Ajanchandra or simply Kunyai, an honorific signaling respect for her role as a spiritual mother.

By the late nineteen sixties, Chandra's circle of followers was growing, including not only rural devotees, but also educated Bangkok youth drawn to her authenticity.

Thailand at the time was undergoing rapid modernization, Bangkok was expanding, students were questioning tradition, and the country was caught between Cold war politics and internal social change.

In this atmosphere, young ties were searching for new expressions of spirituality, something modern yet rooted in tradition.

Kunyai's teachings, simple yet profound, offered a bridge.

It was during this period that she met a young man who would change the trajectory of her life and of Thai Buddhism.

Chaiabun Sudipoll, a Bangkok student born in nineteen forty four who would later take monastic vows as Fradamachaio.

Chaiabin came from a middle class background, intelligent and ambitious, but disillusioned with material life.

He encountered Kunyai in the late nineteen sixties and was captivated by her meditative depth.

Under her guidance, he ordained as a monk and became her closest disciple.

Their partnership was unusual, a poor, elderly nun with little education and a young, university trained monk with charisma and organizational skills, But it was precisely this combination that proved powerful.

Kunyai embodied spiritual authenticity, while Damachayo represented youthful energy, modern communication and vision.

Together they laid the foundations for what would become Watfra Damakaya.

The temple began humbly in nineteen seventy on a donated rice field north of Bangkok and Pathamtani Province.

Followers pitched tents and built makeshift meditation halls from wood to tin.

There was no grand stupa, no sea of marble, just a dusty field and a few dozen committed devotees, but the vision was already ambitious.

Kunyai taught that the Damakaya method of meditation was a universal key to an enlightenment, capable of transforming not just individuals, but society itself.

Damachaio meanwhile saw the potential for growth, organized fundraising, disciplined recruitment, and a message tailored to Thailand's emerging urban middle class.

The founding of Watfra Damakaia coincided with social shifts in Thailand.

The nineteen seventies were a time of rapid urbanization and political upheaval.

Many young ties were moving from villages to cities, caught between traditional Buddhism and the poll of consumer modernity.

The temple positioned itself as a sanctuary for this generation, modern organized and promising both inner peace and worldly prosperity, meditation was marketed not only as a spiritual practice, but as a tool for success, health, and happiness.

Early ceremonies at Watfra Damakaia were strikingly different from those at traditional temples.

Instead of casual, village style gatherings, events were meticulously planned, with rows of devotees sitting in white meditating in unison the atmosphere was orderly, disciplined, and visually powerful.

Photography and media were used strategically to broadcast the image of a new kind of Buddhism, one modern yet ancient, promising both personal enlightenment and social transformation.

By the end of the nineteen seventies, Watfordamakaya had grown beyond its humble beginnings.

The tense gave way to permanent buildings, and land purchases expanded the site.

Donations flowed in not only from rural followers but from Bangkok professionals impressed by the temple's polished style.

Kunyai remained the spiritual heart, revered at as the embodiment of meditative purity, while Damachaio became the public face, drawing crowds with his charisma and ambitious vision.

From its very beginnings, then Domakia carried within it the seeds of both reverence and controversy.

On one hand, it offered a disciplined, modernized form of Buddhism that attracted thousands.

On the other, critics began whispering that the temple's slick organization and heavy fundraising hinted at something more corporate than spiritual.

But in the early years, those whispers were drowned out by the enthusiasm of devotees who saw in Damakaiah, a movement destined to reshape Thai Buddhism Part two, a temple like no other.

The rice field in Pathumtani, where Watfra Damikaia began in nineteen seventy, was unremarkable at first glance.

It lacked the ornate stupas and gilded shrines that defined Thailand's sacred landscape.

Yet from the beginning, the temple declared itself different, not just another monastery, but a vision of Buddhism for a new era.

Its leaders promised enlightenment through meditation, prosperity through merit, and a spiritual revolution that would restore purity to a tradition they argued had drifted from its core.

The central practice that defined the temple was Domakayah meditation, a method rooted in the teachings of Framnkoltep Muni of Watpaknam in Bangkok earlier in the century.

The technique emphasized concentration on the center of the body, visualizing a sphere of light and focusing until an experience of inner luminosity.

The so called Damakaya emerged for traditional Theravada practitioners, this was an unusual interpretation.

For followers of Kunyai Chandra and the young Fradamachaiyo, it was nothing less than the rediscovery of Buddhism's original path to enlightenment.

Meditation at Wat Fradamakaya was presented with an orderliness rare in Thai temples of the time.

Hundreds of followers, dressed in simple white clothes, sat cross legged in perfect rows, eyes closed palms, resting gently, breathing together in silence.

At large events, the symmetry was striking, resembling not the casual gatherings of village Buddhism, but a choreographed display of collective discipline.

For visitors, it created a powerful impression.

Here was a temple that felt futuristic organized.

The appeal was particularly strong for Thailand's rising middle class.

The nineteen seventies and nineteen eighties were decades of transformation in Thailand.

Economic growth fueled migration from villages to Bangkok and other cities.

Families who had once lived in subsistence farming now sought education, careers, and stability in urban life.

Yet modernization brought spiritual dislocation.

Many found that traditional village temples, with their informal rituals and reliance on donations for small merit making, felt out of step with their new lives.

Watfradamakaya filled this gap, presenting itself as a temple for educated urban ties who wanted both spirituality and success.

The temples, sermons and publications spoke directly to this audience.

Merit making.

The act of giving to temples to accumulate positive karma was framed in pragmatic, even transactional terms.

Donations were not just pious acts, they were investments in prosperity, health, and social status.

Meditation was not only for monks, but for office workers and professionals, a practice that could sharpen focus, reduce stress, and ensure success in business.

Enlightenment was recast not as an unreachable goal of ascetics, but as something accessible to anyone willing to sit in meditation and follow the teachings of the temple.

The architecture mirrored this vision, as donations poured in wat for Damakaia expanded beyond its humble wooden halls.

By the early nineteen eighties, concrete structures rose from the field, sleek and modern, rather than ornate and traditional.

Unlike the multi tiered roofs and golden finials of classic Thai temples, Domakia's buildings were simple, geometric, and futuristic.

The message was clear.

This was not about preserving the past, but about building the future.

At the heart of the expansion was the vision of a world temple, a place that could gather millions, not just hundreds.

Leaders spoke of building a Buddhist city, a sanctuary that could stand as the center of a global movement.

This ambition set wat for Damakia Apart.

Where most temples operated locally serving their immediate communities, Damakaiah thought in terms of scale, media, and international reach.

The temple's events reflected this ambition.

During major ceremonies, tens of thousands gathered, filling vast fields in orderly rows.

Aerial photographs circulated in newspapers showing seas of white clad meditators, a spectacle that impressed supporters and unnerved critics.

The visual message was potent Buddhism could be modern, disciplined, and massive.

Where other temples leaned on centuries of tradition, Damakaya leaned on spectacle and scale.

Critics soon noted the heavy emphasis on fundraising.

Sermons emphasized the karmic benefits of donating, sometimes linking specific donation amounts to specific promises of merit.

Some followers were encouraged to give cars, land, or large sums of money, and assured that their generosity would secure both worldly prosperity and a favorable rebirth.

For urban professionals climbing the social ladder, this was appealing.

Donations became not only a way of giving back, but a way of investing in both this life and the next.

Despite criticism, the temple's popularity soared.

By the late nineteen eighties, Watfra Damakaya had become one of the most visited temples in Thailand, especially among educated and affluent ties.

It attracted not only lay deputees, but also university students, corporate workers, and even politicians.

Its meditation courses spread into schools and offices, its publications filled bookstores, and its leaders cultivated media savvy images that contrasted sharply with the often rural and understated demeanor of traditional monks.

Central to this image was Fra Damachaio, who became the charismatic face of the temple.

Tall youthful and articulate.

He embodied the modern monk, a spiritual leader, comfortable in front of cameras, able to speak to both farmers and professionals.

Kunyai Chandra remained the revered spiritual mother, embodying authenticity and purity, but it was Damachaio who turned vision into organization.

His ability to inspire donations, manage expands, and craft a message of prosperity made him indispensable.

By the close of the nineteen eighties, Watfridama KaiA had become a phenomenon.

What had begun as a rice field meditation center was now a sprawling temple complex drawing tens of thousands.

It promised enlightenment through meditation, prosperity through giving and belonging.

For many, it was Buddhism reborn for a modern world.

For others, it was a troubling departure, a movement that blurred the line between spirituality and corporation.

The seeds of future controversy were already visible, but in those early decades they were drowned out by enthusiasm for middle class ties seeking both faith and success.

Wat fraud Damikaia was a temple like no other.

Vast, futuristic, and full of promise.

Part three, Faith and Fortune.

By the dawn of the nineteen nineties, Watfrau Damachia was no longer just a temple on the outskirts of Bangkok.

It had become a movement with national momentum, and under the leadership of Fradamachaio and Kunyai Chandra, its ambitions soared.

The vision was no longer limited to a meditation center or a gathering place for devotees.

It was to be a world Buddhist headquarters, a spiritual metropolis that could shape not only Thailand's future, but Buddhism's global image.

The temple's fundraising efforts became legendary.

Unlike traditional temples, which survived on modest donations and small merit making acts from local villagers, Watfrau Damikaya operated with a corporate style strategy.

Sermons framed giving as investment.

The more you donated, the more spiritual interest you accumulated.

Merit was no longer vague.

It was calculable.

Suggested donation tears promised corresponding karmic rewards from worldly success in business to the guarantee of favorable rebirths.

Campaigns were sleek, coordinated and unashamedly ambitious.

By the early nineteen nineties, these campaigns fueled rapid expansion.

Vast tracts of land were around the original rice field, transforming Pathomtani into a construction site of monumental proportions.

Devotees were urged to give land, deeds, vehicles, jewelry, and savings.

In return, they received recognition, ceremonies, public praise, and a sense of belonging to a movement destined to change the world.

At the center of this expansion was the construction of the Damakaya Setia, an immense golden dome designed to house a million Buddha images.

Planned as the largest stupa in modern history, it symbolized both the temple's ambition and its controversy.

Traditional stupas in Thailand were ornate, multi layered, and tied to centuries of architectural evolution.

The Damakaya Setia, by contrast, resembled a gleaming ufo landed in the rice fields, a massive hemisphere studded with golden Buddha statues.

Futuristic and other worldly.

For supporters, it was breathtaking, a visual declaration that Buddhism could be as bold and modern as any global religion.

For critics, it was a sign that the temple had strayed from humility, turning faith into a brand.

As the Stupa arose, so did the scale of Domakiah's events.

Ceremonies drew tens of thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, of white clad followers meditating in unison.

Before the Golden Dome, aerial photographs showed seas of people stretching to the horizon, arranged in perfect symmetry.

These images were splashed across newspapers, television, and eventually the Internet, reinforcing the temple's self image as the center of a new Buddhist era.

International expansion followed.

Domakaiah Meditation centers were established in the United States, Europe, Australia, and across Asia.

Each was a satellite of the Bangkok headquarters, teaching the same methods, organizing donations, and linking far flung Thai diasporas back to the mother Temple.

The movement marketed itself as universal meditation for stress, relief, prosperity, and enlightenment, stripped of local color, but heavy on discipline and order, yet with expansion came criticism.

Scholars of religion began to work and of prosperity Buddhism the idea that Watfra Damakia had adopted a prosperity gospel model, similar to certain Christian televangelists.

Giving was presented not simply as a virtue, but as a transactional path to success.

Wealthy donors were showcased as proof of the doctrine's effectiveness.

They gave generously and their businesses thrived.

The implication was clear, merit and money were linked, and to be prosperous was to be righteous.

For many traditional monks, this was alarming.

Buddhism, they argued, was about renunciation, simplicity, and detachment from material wealth.

Domakia's fundraising campaigns, complete with tiered merit levels, glossy brochures, and public recognition ceremonies, seemed closer to a corporation than a sanga.

Critics accused the temple of commercializing faith, of turning the four Noble truths into an accounting ledger.

Journalists began investigating the temple's finances.

Reports surfaced of massive landholdings, luxury vehicles, and bank counts swollen with donations Allegations swirled that Domachaio himself had accumulated wealth far beyond what was acceptable for a monk, including property and investments.

While temple leaders defended the fundraising as necessary to support their global vision, detractors painted it as exploitation of the faithful.

Despite the criticism, the Temple's popularity only grew.

Thailand in the nineteen nineties was experiencing an economic boom, with new highways, skyscrapers, and malls reshaping Bangkok.

The ethos of prosperity dovetailed perfectly with Domachaia's message give generously, meditate diligently, and enjoy success, both in this life and the next.

For middle class families climbing the social ladder, the temple offered spiritual legitimacy to their ambitions.

At the same time, the temple's messaging cleverly wove together ancient and modern Meditation sessions were framed as timeless, rooted in the Buddha's path, yet the events were choreographed with modern technology, sound systems, lighting, professional event management devoties were given the sense of participating in something both eternal and futuristic.

This duality ancient truth in a modern package was a hallmark of Damachia's appeal.

Still, the criticisms mounted.

In the late nineteen nineties, whispers of financial impropriety became louder, culminating in accusations of embezzlement and fraud.

Damachia was charged with mishandling donations and personally benefiting from temple funds.

Though the charges were eventually dropped or stalled amid political maneuvering, The controversies tarnished the temple's image.

For opponents, it confirmed suspicions that Damakaia was less about enlightenment than empire.

Yet for supporters, the controversies only reinforced loyalty.

Many framed the attacks as persecution, evidence that the temple's success threatened the establishment.

Followers doubled down on donations, eager to defend their spiritual home.

By the close of the nineteen nineties, what for Damakiah stood not just as a temple, but as a global movement.

Vast, wealthy, and polarizing.

It had become, in the words of both critics and admirers of Buddhist corporation.

Its leaders denied the label, insisting that their vision was spiritual, not financial, But the Golden Dome, the endless fundraising drives, and the vast organizational apparatus told another story, one where faith and fortune had become inseparable.

Part four teachings of the True Self amid the Golden Domes and mass meditation events of what for Damakiah.

The controversy that most sharply divided the temple from the mainstream Buddhist establishment was not only about money.

It was about doctrine, a particular interpretation of the nature of the self, enlightenment and the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice.

Where centuries of Theravada tradition had insisted on anata the doctrine of no self, Domakia teachers proclaimed the discovery of a luminous, eternal self at the heart of meditation.

The origins of this teaching lay in the meditation method inherited from Watpoknam and Fromongcoltep Muni, who had popularized Damakaiah meditation in the early twentieth century.

Practitioners were instructed to focus on the center of the body, visualizing spheres of light until they perceived an inner radiance that expanded into the experience of the Damakaya.

At the culmination of practice, they reported visions of a radiant Buddha like form within themselves, described as pure, eternal, and indestructible.

For many meditators, these experiences were transformative.

They spoke of peace, clarity, and bliss, unlike anything they had known.

For teachers at Wapaknam and later at Watfra Damakaiah, the conclusion was obvious.

This Innerbudda body, this radiant core, was the true self.

To reach it was to reach Nirvana.

But to orthodox Theravad monks and scholars, this was heresy.

The central teaching of Theravada Buddhism, preserved in the Polycnon was that all phenomena are impermanent, unsatisfactory daka, and not self anata.

To claim that enlightenment revealed an eternal, luminous self was to overturn the very foundation of the tradition.

Critics argued that Damakia had smuggled a Hindu or Mahayana concept of otman, an eternal soul, into a tradition that had explicitly rejected it.

By the nineteen nineties, as Damakaia grew into a national force, the doctrinal controversy erupted into public debate.

Senior monks in the Thai Sanga Council warned against teachings that contradicted the principle of no self.

Academic scholars published articles denouncing the temple's claims as distortions of scripture.

Buddhist universities debated whether Damakiah represented innovation or corruption.

Watfra Damakia defended itself with vigor.

Leaders argued that the luminous self was not a soul in the Western sense, but the realization of nirvana, a state beyond impermanence, beyond suffering, beyond the ordinary self.

They pointed to passages in obscure texts that could be interpreted as affirming and inner radiance.

They insisted they were not rejecting Theravada, but restoring its original insight, lost or obscured through centuries of transmission.

For lay followers, the debate mattered less than the experience itself.

Thousands of meditators reported visions of inner light, bliss, and a radiant form during practice.

These experiences felt real, compelling, and life changing to them.

The doctrinal disputes of scholars seemed abstract.

What mattered was that Domakaiah meditation worked, producing peace and joy in daily life.

Yet for the Thai Buddhist establishment, the stakes were higher.

Thailand's religious identity had long been tied to Theravada orthodoxy, with monks acting as moral guides and interpreters of scripture.

To allow Domakia's doctrine of a true self to stand unchallenged risked undermining the Sanga's authority.

Some feared it would splinter Thai Buddhism into rival schools, or, worse, align it with prosperity teachings that already raised eyebrows Internationaltionally, some monks called Domakiah occult, accusing it of misleading the faithful with promises of prosperity and eternal selfhood.

Others defended it as a legitimate, if radical reinterpretation of Buddhist practice.

The controversy was not merely theological, but political.

The Temple's enormous wealth and mass following gave it influence that rivaled the state backed monastic establishment.

The True Self doctrine became a lightning rod for broader anxieties about modern Buddhism.

Was Watfra Damikaia innovating to meet the needs of a new era, or was it distorting Buddhism into a corporate faith that contradicted its essence.

Could experiences of luminous meditation be reconciled with the textual insistence on no self?

Or were they irreconcilable.

For devotees inside Damakiah, the answer was clear.

Meditation revealed light, peace and truth.

If scripture seemed to deny it, then scripture must have been misinterpreted.

For critics, the answer was equally clear.

Centuries of Theravada tradition could not be discarded for subjective, no matter how radiant.

By the late nineteen nineties, the controversy had hardened lines.

Damakia continued to expand, indifferent to criticism, while the Songa Council issued warnings and attempted investigations.

The clash over doctrine ensured that Damakaia would never be merely another large temple.

It was now a theological challenger claiming to restore the Buddha's original truth, while the establishment condemned it as heretical.

Part five Crises and crackdowns.

By the late nineteen nineties, Watfra Damikaia was no longer a movement admired only for its meditation discipline or futuristic architecture.

It had become one of the most powerful religious institutions in Thailand, commanding hundreds of thousands of followers, a sprawling international network, and donations that flowed in at unprecedented levels.

But as its influence grew, so too did suspicions.

The temple's prosperity gospel, its doctrine of the true self, and its corporate style fundraising had already earned it critics.

What came next would turn criticism into full scale scandal and eventually a confrontation with the Thai state.

The first major storm erupted in nineteen ninety nine to two thousand, when Fraudamachaio, the temple's abbot, was accused of embezzlement and land fraud.

Reports emerged that land, deeds and assets donated by followers to the temple had been transferred into his personal name.

Journalists uncovered evidence of luxury properties and bank accounts linked to him.

For a monk in a tradition that prized simplicity and detachment, the allegations were explosive.

The Thai Soga Council, under pressure from both the government and the media, initiated an investigation.

The charges against Domachaio included mismanagement of temple funds personal enrichment, and failure to hand over assets to the monastic order as required by law.

Critics pointed to the Temple's relentless fundraising campaigns, with the promises of prosperity and car rewards tied to specific donation amounts, as a system ripe for exploitation.

Domicio defended himself, claiming that assets were held in his name for administrative reasons and that all funds were used for religious purposes.

The Temple launched a public relations campaign presenting him as a victim of persecution by jealous rivals and secular politicians who feared Domachaia's popularity.

Followers rallied in his defense, gathering in the tens of thousands to meditate in solidarity, framing the accusations as an attack not just on one monk, but on their entire movement.

For years, the scandal dragged on, legal cases stalled, investigations bogged down, and political interests shifted.

At times, it seemed as though Domachaio might be defract even imprisoned, but he remained in place, his position protected by the Temple's massive influence, its wealthy donors, and its ability to mobilize crowds larger than any political rally.

By the mid two thousands, the cases had largely fizzled, leaving critics frustrated and supporters triumphant.

The Temple's survival through the nineteen ninety nine to two thousand scandals set a precedent.

Watford Damikaia was too large, too wealthy, and too politically connected to be easily dismantled, but it also ensured that it remained under suspicion.

The next and most dramatic confrontation came more than a decade later, in twenty sixteen twenty seventeen, when Watfra Damakaia once again became the center of national attention.

This time, the charges against Damachio escalated beyond mismanagement.

He was accused of money laundering and receiving billions of bought embezzled funds linked to a major financial scandal involving the Klong Chan Credit Union cooperative.

Prosecutors alleged that Temple Networks had received large donations traced to fraudulent schemes and that Domachaio personally benefited.

By this point, Domachaio was elderly and in poor health, but the allegations threatened not only his reputation but the temple's entire empire.

When authorities attempted to a arrest him in twenty sixteen, thousands of monks and lay followers surrounded the temple grounds, meditating in rows as a human shield.

The temple's massive complex in Patham Tani became a fortress.

In February twenty seventeen, the tai Junta government declared the temple a controlled area and deployed thousands of police and soldiers to lay siege to the compound.

Checkpoints were established, drones circled overhead, and the temple's gates were sealed.

Authorities insisted they were carrying out a lawful arrest.

Temple spokesman claimed the government was persecuting Buddhism.

Inside the standoff lasted weeks.

Monks and lay devotees staged nonviolent resistance, sitting in meditation postures to block entry.

Rumors swirled in the media that Damachaio was hiding in secret tunnels, that he had already fled, that negotiations were happening behind the scenes.

Daily press conferences framed the drama as a clash between state authority and in religious devotion.

Yet, despite the massive show of force, the siege inconclusively, authorities never apprehended Damachio.

Some claimed he had been smuggled out of the compound, others suggested he remained inside, shielded by loyalists.

To this day, his exact fate remains unclear.

Officially, he became a fugitive wanted on charges of money laundering and land fraud.

Practically he vanished from public view, leaving the temple to be managed by his deputies.

The siege of Watfra Damachaia was one of the most dramatic confrontations between the Thai state and a religious institution in modern history.

For weeks, images of monks facing off with police flooded National and international media.

Critics called the temple a lawless empire.

Supporters claimed it was being unfairly targeted by a military government seeking to control Buddhism.

In the end, the temple survived.

Its vast complex remained intact, its daily operations continued, and its followers remained loyal.

The charges against Damachaio lingered, but without his arrest, the legal process stalled.

For many, the episode demonstrated not weakness, but resilience.

Damakaia had faced the full force of the state and endured the twin crises.

The financial scandals of nineteen ninety nine to two thousand and the siege of twenty sixteen twenty seventeen cemented Watford Damakia's reputation as both powerful and polarizing.

To critics, it was proof that the temple had strayed into dangerous territory, a corporate empire that placed itself above the law, a distortion of Buddhism's core teachings.

To devotees, it was evidence that their movement was authentic, persecuted precisely because it was spiritually effective and socially influential.

Through it all, one fact remained undeniable.

Damakia was no ordinary temple.

It had become an institution capable of challenging the state itself, a religious empire that blurred the line between devotion, money and power.

Part six power, persistence, and paradox.

In the years since the twenty sixteen twenty seventeen siege, Watford Damakia has remained both a mid monument to devotion and a symbol of controversy.

Its golden dome still rises from the rice fields of Pathumtani like a sun of metal and glass, drawing tens of thousands of devotees in white to sit in rows before it.

The scale alone is staggering, ceremonies that resemble mass rallies, meditation events broadcast live to audiences across continents, and international branches that stretch from California to Sydney, from London to Nairobi.

Despite the fugitive status of its abbot, despite the legal clouds that hang over its leadership, the Temple persists vast and resilient.

Domakia today embodies paradox.

On one hand, it continues to function as a meditation movement.

It centers abroad present themselves as cultural embassies of Thai Buddhism, offering meditation courses framed as stress relief for modern life.

Participants describe the serenity of group practice, the clarity of Damakaiah meditation, and the comfort of belonging to an international community.

On the other hand, critics note that every horse is tied to fundraising, every practice linked to donations, and every expansion dependent on a theology that equates wealth with merit.

The Temple's global reach is undeniable.

Domakaya centers have become fixtures in major cities, often appealing to diasporaties but also to Western seekers drawn by its polished presentation.

Its branding is consistent futuristic architecture, orderly gatherings, and a message of prosperity through meditation.

Unlike traditional Thai temples abroad, which often serve as cultural sanctuaries for immigrants, Domakaia markets itself as universal Buddhism's stripped of cultural clutter, wrapped instead in discipline, Yet its controversies endure.

Scholars of Buddhism continue to challenge the temple's doctrine of the luminous True Self, pointing out its incompatibility with Theravada orthodoxy.

Critics in Thailand warned that Damakaya has blurred the line between religion and corporation, turning merit making into a financial exchange.

Journalists remind of audiences of the unresolved allegations of money laundering and fraud.

Each time the temple organizes a mass event, debates resurface.

Is this a new model of Buddhism for the modern world or a distortion of the tradition's heart for former members?

The answer often lies in their personal experiences.

Some describe the joy of belonging to a disciplined community, the clarity of meditation, and the sense of being part of something larger than themselves.

Others recall the pressure to donate beyond their means, the shame imposed when contributions fell short, and the growing sense that the temple's promise of prosperity was less about karma than about control.

Survivors of the movement speak of financial ruin of families divided over loyalty to the Temple, of guilt when expectations of wealth or health failed to materialize.

Still, for those who remain, Damachia is not a scandal but salvation.

They see in its massive stupa, a beacon of faith, in its orderly meditation gatherings, a glimpse of globe, in its teachings of inner light, a source of meaning in a chaotic world.

Where critics see exploitation, devotees see discipline, where opponents see corporate branding, believers see the modernization of Buddhism.

The paradox is inescapable wat for Damakaia has outlasted investigations, scandals, and even a siege by the Thai military.

Government.

It continues to thrive, raising funds, expanding globally, and inspiring devotion.

It is at once a meditation movement and a business enterprise, a site of spiritual transformation and of political suspicion, a community of seekers, and a fortress of power.

What does its story reveal?

That religion, wealth and control are often entangled, especially in times of rapid modernization, That devotion can inspire generosity but also be exploited for profit, and that movements promising clarity, prosperity, and purity can draw immense crowds, even when shadowed by scandal.

Domakia is not merely a tie story.

It is a global reminder of the ways in which faith can be shaped into both and spectacle.

As we leave the gleaming domes of Pathumtani, we turned to another hidden cult, one that flourished not in a temple city, but in a quiet compound in the American Midwest.

In the early two thousands, a man named Lou Castro, later revealed to be Daniel Perez, created a community in Kansas known as Angels Landing.

He promised his follower's wealth, safety, and supernatural powers, presenting himself as a prophet touched by other worldly forces behind the facade lay manipulation, fraud and murder.

By twenty fifteen, Perez was convicted in court and the true story of Angels Landing was revealed, a cult like group bound by deception, abuse, and the power of one man's control.

That's next time.