Episode Transcript

Welcome to Hidden Cults, the podcast that shines a light into the shadows.

Here we explore the strange, the secretive, and the spiritually seductive.

From fringe religions to doomsday prophets, from communes to corporate empires.

These are the movements that promised meaning and sometimes delivered something far more dangerous.

I'm your host, and in each episode, we uncover the true stories behind the world's most controversial cults, the leaders who led them, the followers who followed, and the echoes they left behind.

If you or someone you care about has been impacted by a cult, you're not alone.

There is help.

Whether you're still inside a cult or trying to process what you've been through, support is out there.

You can find organizations and hotlines in the description of this episode.

You deserve freedom, healing, and a life that's truly your own.

Reach out.

The first step is often the hardest, but it's also the most powerful.

If you'd like to share your story and experiences with a cult, you can email it to me and I will read it on a future Listener Stories episode.

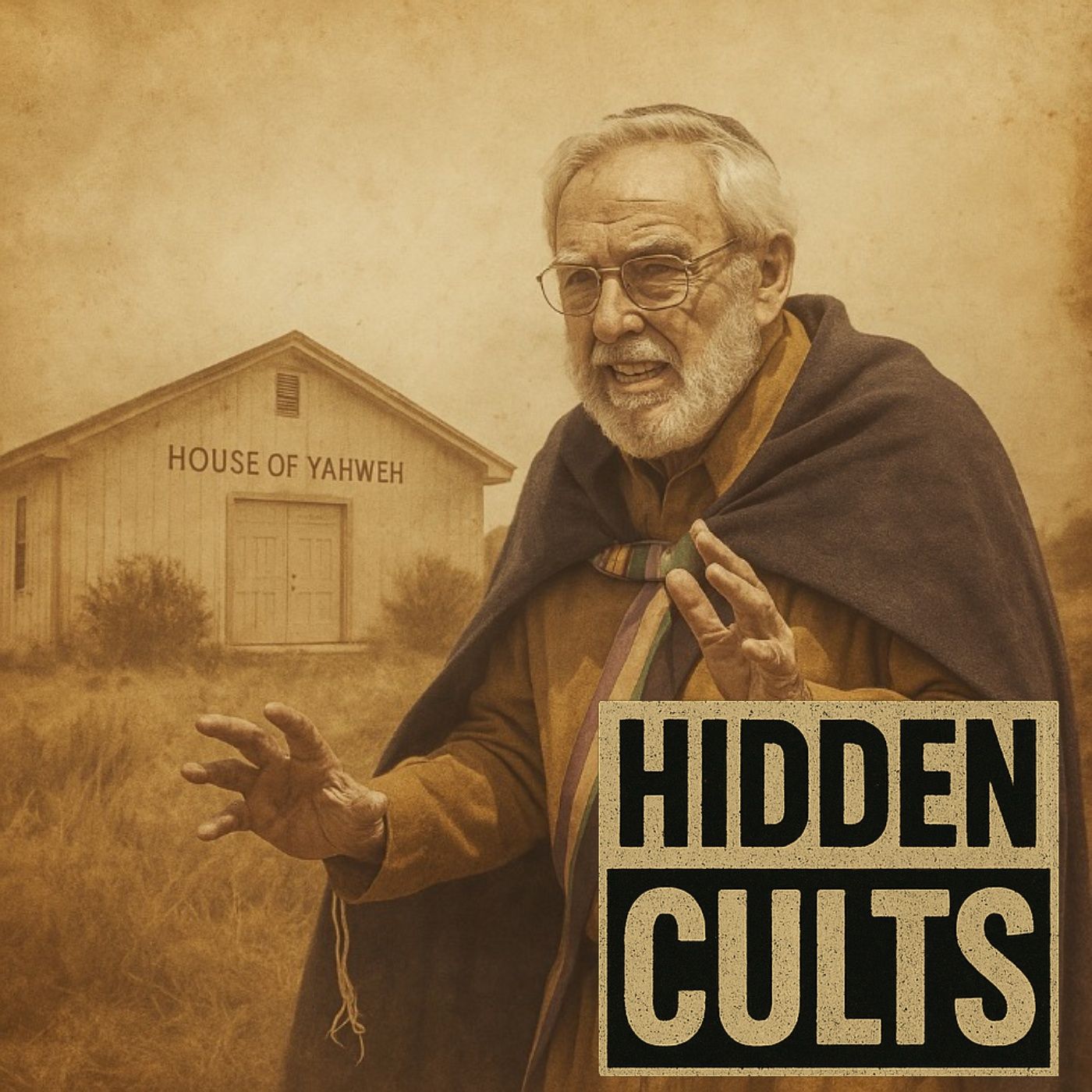

Your anonymity is guaranteed always today's episode, let's begin The House of Yahweh, Part one the prophet of Abilene.

In the flat plains of West Texas, where the land stretches wide and the sky seems to press down forever, a man named Ysrael Hawkins began building what he believed would be the true House of God.

To his followers, he was a prophet chosen to restore the world's lost faith.

To outsiders, he was one more voice in the long line of self appointed messiahs claiming divine authority on American soil.

But before the name Yisrael ever appeared on a letterhead or a sign, there was Buffalo Bill Hawkins, a preacher, husband, and father who came of age in a country still shaped by revival tents and Bible prophecy.

Born in nineteen thirty four in Oklahoma, Hawkins grew up in the rural poverty of the dust Bowl Generation.

Like many families in that time and place, his household was defined by hard labor and church going.

The Bible wasn't just a book, It was the center of life, the lens through which every drought, death, and hardship was explained.

He was raised in the Church of God, a Protestant denomination with roots in the holiness movement known for its literal interpretation of scripture and its emphasis on moral purity.

For a young boy like Hawkins, this strict faith offered both structure and promise, the idea that the world might be redeemed if only the faithful lived according to God's true law.

By his teens, Hawkins had become known for his intelligence and confidence.

He spoke with authority, often quoting long passages of Scripture from memory.

Those who knew him described a boy already can convinced that he was destined for something greater.

He began preaching informally in his youth and later trained under various ministers in the Church of God network.

But even then Hawkins stood out not for humility, but for a growing belief that the truth had been corrupted.

In the late nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties, the American religious landscape was shifting.

The postwar boom brought prosperity and optimism, but also a wave of new spiritual movements, from pentecostal revivals to apocalyptic sex warning that the end was near.

Amid this ferment, Hawkins developed an obsession with what he saw as a fundamental error in Christianity, the use of the names God and Jesus.

In his view, those words were mistranslations, pagan impostors, replacing the true names of the divine.

He argued that God was a generic title, not the name of the creator, and that Jesus was a Greek distortion of the Messiah's real Hebrew name Yeshua.

To Hawkins, this was no small matter.

It was evidence that the entire Christian world had been deceived.

The more he studied, the more radical his conclusions became.

He came to believe that all modern churches, even his own denomination, had strayed from the path.

The true faith, he said, could only be restored by returning to the Hebrew names and laws of the Old Testament.

This belief would become the foundation of his future empire.

By the nineteen seventies, Hawkins's religious intensity began to divide those closest to him.

He clashed with other Church of God ministers, accusing them of hypocrisy and compromise.

His sermons became more confrontational, and his focus shifted increasingly toward prophecy, especially the coming end of the age.

Meanwhile, his personal life grew strained.

Family members later described him as charismatic but controlling a man whose certainty left little room for dissent.

He preached long hours, studied deep into the night, and began drafting letters to church leaders accusing them of hiding the truth.

Eventually the split became complete.

Hawkins left the Church of God altogether, convinced that God had called him to start anew.

He was not the only one.

Across America, similar breakaway sex were forming, often led by men who claim to have received divine revelation about the true church.

For Hawkins, though, this wasn't just about doctrine, it was about identity.

In leaving the church, he left behind the last tie to his old self.

He began calling himself y Israel, a Hebrew transliteration of Israel, meaning he who struggles with God.

It was both a name and a declaration that he alone had wrestled with scripture and emerged with truth.

In nineteen eighty, Hawkins settled in Abilene, Texas, a conservative town in the heart of the Bible Belt.

It was here, among cattle ranches and Baptist churches that he founded in the House of Yahweh.

At first, it was a modest congregation, a few families gathering in a rented space to study the Hebrew scriptures and listen to Hawkins's teachings.

He preached that humanity was living in the end times, that the beastly system of false religion was about to fall, and that only those who used the true name of Yahweh would be saved.

To his small but growing flock.

His words carried an electric urgency.

He promised that they were part of a sacred restoration, the rebuilding of the original faith of the Patriarchs, stripped of centuries of corruption.

He quoted scripture constantly, warning that the world's churches were deceived by Satan's translators.

He pointed to every natural disaster, every war, every moral panic as proof that prophecy was unfolding before their eyes.

By the mid nineteen eighties, the House of Yahweh had established its own compound on the outskirts of Abilene.

There were houses for members, small farms, a print shop, and a sanctuary where Hawkins preached each Sabbath.

Members wore modest clothing, used Hebrew phrases, and followed Old Testament dietary laws.

Hawkins transformation was complete.

He now spoke not as Buffalo Bill, the preacher from Oklahoma, but as Yesfrael Hawkins, the Witness of Revelation.

He claimed that God had chosen him to warn the world of its impending disc instruction and to prepare a faithful remnant for the coming Kingdom.

He began publishing newsletters and booklets filled with his unique interpretations of scripture, focusing heavily on the use of sacred names and the importance of following the six hundred and thirteen Laws of the Torah.

He argued that Christianity had been hijacked by Rome and that his church alone represented the restored path of salvation.

To followers, he was a visionary reclaiming ancient truth.

To critics, he was a preacher turned prophet by ego and obsession.

But one thing was certain.

The House of Yahweh had arrived, and what began as a small gathering in rural Texas would soon grow into an international movement, one that combined Old Testament law, apocalyptic prophecy, and authoritarian control in ways that would unsettle even the most devout believers.

Part two.

A Name above all names.

By the mid nineteen eighties, the House of Yahweh had become more than a church.

It was a movement with its own language, laws, and vision of salvation.

In Abilene, Texas, the compound grew into a small kingdom, surrounded by fences and faith, governed by one man who claimed to speak for the Creator himself.

At the center of it all was a single idea.

The name of God had been hidden, and only y Israel Hawkins had restored it to outsiders.

Hawkins's sermons sounded familiar at first.

They quoted from the same Bible as every other preacher in the Bible Belt, but the words he spoke carried a crucial difference.

He replaced God with Yahweh and Jesus with Yeshua.

These weren't just stylistic choices.

To Hawkins, they were the difference between salvation and damnation.

He taught that the names God and Lord were of pagan origin, deceptive substitutions introduced by Satan to lead humanity astray.

Only by using the true names, he said, could one connect to the Creator.

In his writings, he declared that all major Christian denominations were false churches, worshiping a counterfeit deity.

The Catholic Church, in his view, was the beast of revelation.

Protestantism was a splinter of the same corruption and modern Judaism, he claimed, had lost touch with its own divine hairline.

Only the House of Yahweh, he said, stood apart, the one body that had rediscovered the sacred key.

For his followers, this teaching created a powerful sense of exclusivity.

Every prayer, every conversation, every greeting became infused with meaning.

Praise Yahweh replaced praise God.

Yashua's Peace became a common farewell.

To use any other name was blasphemy.

The theology was simple but absolute.

If you didn't call upon Yahweh, you weren't calling upon the true Creator at all.

Alongside the restoration of the divine name came the restoration of the law.

Hawkins insisted that Christianity's focus on grace had corrupted the faith.

The law, he said, was never done away with.

Members were expected to obey the six hundred and thirteen commandments of the Torah, dietary laws, Sabbath observance, dress codes, and purity rituals.

They were forbidden to eat pork or shellfish, to wear blended fabrics, or to participate in holidays like Christmas and Easter, which Hawkins called pagan abominations.

The calendar of the House of Yahweh followed a ancient Hebrew reckoning, with feasts timed by lunar cycles.

Every seventh day was the Sabbath, a period of strict rest and worship.

Women were told to dress modestly, covering their hair and arms.

Men grew beards as a sign of obedience.

The community's daily life was governed by ritual, from morning prayers to communal meals to sunset devotions.

But these outward signs mask something deeper, a system of control that reached into every part of life.

Hawkins interpretation of scripture left no room for personal interpretation.

To question his teachings was to question Yahweh himself.

Followers were told that disobedience was rebellion against the Creator, and that those who left the faith would face divine punishment in the coming apocalypse.

This combination the sacred name, the ancient law, and the authority of one man created a theology of total submission.

By the late nineteen eighties, Hawkins had taken on a new title, The Witness of Revelation.

He claimed that the Bible foretold two witnesses who would rise in the last days to warn humanity before the final judgment.

One would come from the East, the other from the West.

In Hawkins's view, he was that Western witness, the one chosen to deliver Yahweh's message to a dying world.

He wrote in his books that he had been shown these truths through divine inspiration, that every event in world history, from the Gulf War to the fall of the Berlin Wall was part of Yahweh's unfolding plan.

He warned of nuclear destruction, famine, and disease, all of which he said would strike unless humanity repented and returned to the true name.

Followers saw him as more than a teacher.

They called him the Overseer, a title implying both spiritual and practical control.

His word carried divine weight.

The compound outside Abilene became the physical embodiment of this theology.

It was both sanctuary and fortress, a place set apart from what Hawkins called the sinful world.

Members gave up their old lives, jobs, and often family ties to join.

Many lived on or near the property, working in communal businesses, publishing literature, or tending the gardens and livestock that sustained the community.

Inside the compound, the atmosphere was one of constant devotion.

Children were taught Hebrew words alongside English.

Members studied hawkins books with titles like the Mark of the Beast, Unveiling Satan, and the Two Witnesses as though they were Scripture themselves.

Everything revolved around preparation.

The world outside was doomed, Hawkins said, but the House of Yahweh would endure.

He promised that those who kept the laws and honored Yahweh's name would survive the final war and inherit the new kingdom on Earth.

Over time, the House developed its own social order.

Marriages were arranged through leadership approval.

Members were encouraged to cut ties with unbelieving relatives.

Even medical care was subject to Hawkins's interpretation of scripture.

Vaccines, blood transfusions, and certain medications were discouraged or forbidden.

For followers, these restrictions were justified by faith.

To live within the laws was to live in truth, to disobey, to betray Yahweh.

But for ex members the same system looked like psychological captivity.

Former followers later described an environment where every action was scrutinized, where fear of punishment, both spiritual and social, kept them silent.

One ex member told reporters that even thoughts could feel dangerous, you start to police your own mind.

You're always asking would this thought please Yahweh?

Would this make the overseer angry?

Inside, obedience was equated with salvation outside, disobedience meant death, if not by divine wrath, then in the nuclear fire that Hawkins said would soon consume the world.

By the nineteen nineties, the House of Yahweh had become a self sustaining society with its own calendar, economy, and moral code.

Hawkins's sermons were broadcast through newsletters, recordings, and later television and the Internet.

The compound drew converts from across the United States, as well as from Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Outsiders saw a tight knit religious community, but to those within, it was a total world, one where every truth, every command, every breath passed through the filter of one man's interpretation of Yahweh's will.

The theology of Sacred Names had begun as a call for purity, it ended as a doctrine of control.

Part three Life in the House.

By the time the nineteen nineties arrived, the House of Yahweh had evolved into a world unto itself, closed, disciplined, and loyal to one man.

Behind the gates of the compound outside Abilene, Texas, life was built around ritual law and surveillance.

Disguised as spiritual care, members believed they were living the way of the Patriarchs, restoring the purity of ancient Israel.

In truth, they were living under the complete authority of Ysrael Hawkins, a man who had become both profit and ruler.

The first thing newcomers noticed upon arrival was the isolation.

The compound sat in open country, quiet, dry, and far removed from the noise of city life.

Members referred to it as the House, and within its boundaries Hawkins laws replaced those of the state.

Houses were modest, often built repaired by the members themselves.

The community shared meals, prayed together, and followed a calendar of sacred feasts that mirrored the Old Testament.

But for every public show of unity, there was an unspoken division the inside world and the outside world.

Outsiders were seen as of the nations, corrupted by false religion and destined for destruction.

Members were taught to minimize contact with anyone who didn't share their faith, even family letters from ex members describe how parents were urged to cut off children who left the group, and how spouses who doubted hawkins teachings were seen as spiritually diseased.

To remain pure meant to remain separate rules for every breath.

Every part of life inside the compound was regulated by law, not civil law, but what Hawkins called Yahweh's law.

Dress codes were strict.

Women wore long skirts, sleeves past the elbow, and often covered their hair in public.

Makeup and jewelry were considered signs of vanity, condemned as remnants of Babylonian culture.

Men wore beards, simple shirts, and loose fitting pants.

Any form of adornment was discouraged.

The only beauty worth displaying was obedience.

Dietary laws were equally detailed.

Pork, shellfish, and processed foods were forbidden.

Members observed the biblical distinction between clean and unclean animals, and food preparation was done according to levitical guidelines.

Some former members later recalled that even the way utensils were washed could become a test of piety.

Sabbath observance was absolute.

From sundown Friday to sundown Saturday, no work was done Members gathered for worship, listened to Hawkins's recorded sermons, and read his writings aloud.

Children were taught to sit still for hours, their small voices joining in the rhythmic chance of Hebrew prayers.

If you followed the rules, life was simple, predictable, even but for those who questioned them, there was no safe space.

Hawkins ruled at the top of a carefully teered system.

Beneath him were elders, men handpicked for their lawy, loyalty, and obedience.

Beneath them were overseers and teachers, responsible for guiding the rank and file.

Every action, from marriage to medical care passed through this chain of authority.

When members sought guidance, they weren't encouraged to pray privately or interpret scripture for themselves.

Instead, they went to an elder who relayed hawkins teachings.

The prophet's words were final.

To disagree was to reject Yahweh's appointed messenger.

Members often addressed Hawkins in reverent tones.

His followers saw him as more than a pastor.

He was a living vessel of truth in community meetings.

His image was displayed on banners and booklets.

His writings were quoted like scripture.

Even his mannerisms, the cadence of his speech, the turns of phrase he favored were mimicked by followers inside the house, individuality faded quickly.

Marriage within the group was tightly controlled.

Members couldn't marry without leadership approval, and unions were often arranged based on status and spiritual standing.

Women were expected to submit completely to their husbands, who in turn were expected to submit to Hawkins.

By the late nineteen nineties, allegations began surfacing of polygamy marriages sanctioned by Hawkins, in which men, including leaders, took multiple wives.

Some women described being pressured into relationships they didn't want, told that their submission would please Yahweh.

More disturbing were reports of child marriages.

Former members and investigators alleged that girls as young as fourteen were promised to older men under the banner of biblical marriage.

These unions, though secretive, were justified by references to Old Testament precedent.

There were also claims of sexual coercion within the leadership, though few reached public courts.

Former members said they feared both divine and earthly punishment if they spoke out in a system where every aspect of life was labeled as sacred.

Even abuse could be disguised as obedience.

Money, too, flowed upward toward Hawkins.

Members were expected to tithe not just ten percent of income, but often more through special offerings or labor donations.

Some sold property or emptied savings accounts to support the church's expansion.

Those who questioned where the money went were reminded that Yahweh saw generosity as faith.

Those who hesitated were told they lacked trust in his profit.

The House of Yahweh built businesses and publishing ventures, from printing operations to farms.

Much of the work was done by unpaid members who believed they were serving the creator.

The result was a self sustaining economy, one that kept followers physically and financially tied to the group.

Survivors describe a quiet, ever present fear that governed life in the House.

The fear wasn't of violence, at least not physical, but of eternal loss.

Members were taught that leaving the House meant forfeiting salvation.

Hawkins warned that those who departed would be destroyed in the nuclear war he said was imminent.

In one sermon, he described defectors as walking dead souls who had cut themselves off from Yahweh's protection.

This fear kept many inside long after doubt began to grow.

Families stayed together, but love was conditional, always tested against loyalty to the prophet.

By the early two thousands, the House of Yahweh was a world sealed tight.

Members wore the same clothing, spoke the same phrases, and read only approved materials.

The compound had guards at its gates and cameras monitoring the perimeter.

To outsiders, it looked like an eccentric but harmless sect.

To insiders, it was the universe.

Everything outside was Babylon, corrupt, doomed, and lost, And at the center of it all stood Ysrael Hawkins, his authority unquestioned, his sermons broadcast to every corner of his small empire.

What began as a search for the true name of God had become a system of spiritual captivity.

Part four.

The end is always near.

For most of the outside world, the year two thousand passed with little more than fire works and a sigh of relief.

But inside the fenced in world of the House of Yahweh in Abilene, Texas, it was no ordinary turning of the calendar.

It was supposed to be the end of days.

At least, that's what Usrael Hawkins had preached for years, and for his followers the message was clear.

The world would end soon, but they would survive it.

The obsession with prophecy had been part of Hawkins's teaching from the beginning.

Ever since the nineteen eighties, his sermons had been steeped in numbers, scripture, and predictions of destruction.

He claimed to decode hidden timelines from the Book of Daniel in Revelation, arguing that the Bible contained mathematical clues to the exact hour of the world's judgment.

Each war, each drought, each political shift became a sign.

Hawkins would cite headlines about the Soviet Union, the Gulf War, or the spread of disease as proof that humanity was sliding toward catastrophe.

Nuclear fire, he said, would cleanse the earth.

In nineteen eighty seven, he declared that the nuclear holocaust prophesied in Revelation would begin in that same year.

It didn't, but rather than back away, Hawkins simply reframed the prophecy.

The destruction had been delayed by Yahweh's mercy.

He explained, a test to see who would remain faithful.

It was a pattern that would repeat again and again over the decades, prophecy failure, revision, and renewal a timeline of doom.

By the early nineteen nineties, the House of Yahweh's apocalyptic narrative had become its heartbeat.

Hawkins published booklets detailing how ancient prophecies aligned perfectly with modern events.

He calculated dates using Hebrew calendars, lunar cycles, and obscure numerology.

In nineteen ninety nine, he predicted that nuclear war would erupt within two years, the ultimate fulfillment of his decades long warnings.

Members prepared by storing food, purifying water, and rehearsing survival plans.

The compound buzzed with urgency.

When nothing happened, the disappointment was quietly redirected.

Hawkins told followers that Yahweh had granted a brief extension, a divine reprieve, to allow more people to repent.

Those who doubted were accused of lacking faith.

By two thousand and seven, a new date emerged, September twelfth.

This time, Hawkins said the evidence was absolute.

Nuclear war is coming, he warned, and only those who are sealed by Yahweh will be protected.

Followers sold property, cut ties with family, and weighted.

Some even withdrew their children from school to stay inside the compound.

The Texas heat bore down, the world kept turning, and nothing happened again.

But rather than break the spell, the failure only deepened it.

Hawkins announced that his prophecy had been misunderstood, that the war had begun spiritually and would soon manifest physically.

The apocalypse, he insisted, was unfolding on a higher plane.

In the House of Yahweh.

Disbelief was more dangerous than failure.

Every mist prophecy became a tool of reinforcement.

The closer the deadline, the stronger the control members who hesitated to follow rules were warned that their disobedience might cost them Yahweh's protection.

When disease outbreaks hit the news from Stars to Ebola to COVID nineteen decades later, Hawkins's sermons returned to the same refrain see the prophecies are true.

He spoke of plagues as divine punishment, nuclear weapons as Yahwe's instruments, and economic collapse as proof of the world's corruption through repetition, fear became faith.

Followers came to see the world's suffering as validation of their beliefs.

When disasters struck elsewhere, they saw it as confirmation that Yahweh had chosen them to survive.

Every world event was a mirror reflecting Hawkin's truth.

Every headline became scripture fulfilled.

These apocalyptic teachings served another purpose.

They sealed the walls of isolation.

If the end of the world was always imminent, then there was no reason to engage with it.

Outsiders, whether family, reporters or investigators, were portrayed as tools of Satan trying to pull believers away from safety.

Members were told that leaving the house meant certain destruction.

Only those inside would be spared when the bombs fell and the nations burned.

This belief turned doubt into danger.

To question Hawkins wasn't just to disagree with a man.

It was to jeopardize one's eternal survival.

Many who wanted to leave stayed out of fear, not of retribution from the church, but of divine annihilation.

As one former member later recalled, you stop thinking about tomorrow, you start thinking about the end.

Every day feels borrowed, so obedience feels like protection.

The House of Yahweh's services became increasingly theatrical.

Hawkins delivered marathon sermons, some lasting hours, filled with apocalyptic rhetoric and elaborate charts predicting nuclear trajectories and timelines.

He pointed to ancient prophecies as though they were news reports.

Yahweh showed me this before it happened, he would say, linking passages from Daniel to modern politics, revelation to radiation, Zachariah to climate change.

To his followers, this was revelation.

To skeptics, it was manipulation cloaked in scripture.

When television crews visited the compound in the two thousands, they often found followers quietly confident that the end was coming any day.

Yahweh's time is not man's time, one said, smiling at the camera.

But his word is sure.

For those within the cycle of failed prophecies wasn't evidence of deceit.

It was proof of testing a divine rhythm of warning and mercy.

Each disappointment reaffirmed that they were living in sacred times.

Through the twenty tens, Hawkins's predictions continued.

He tied world events to his timelines with practiced certainty.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, terrorist attacks, environmental disasters, even the rise of global pandemics, all were stepping stones toward the final judgment.

And still the apocalypse didn't arrive.

But it didn't need to.

The fear itself was enough.

It kept members loyal, isolated, and obedient.

It justified the sacrifices, the poverty, the distance from family.

As long as the end was near, life inside the house made sense.

In sermons near the end of his life, Hawkins softened his tone, but not his message.

Yahwa's prophecy never fails, he said, only man's understanding does.

It was a final safeguard, a way to ensure that, even after death, his word would remain unchallenged.

The doomsday clock in Abilene never struck midnight, but for the people inside the House of Yahweh, it never stopped ticking.

Part five, Law and Judgment.

By the early two thousands, the world outside the compound had started to take notice.

For two decades, y Israel Hawkins had preached the end of days, claiming to speak for the Creator himself.

His followers believed the apocalypse was always moments away, that the chaos of the world confirmed his divine vision.

But beyond the barbed wire fences of the House of Yahweh and Abilene, Texas, questions were growing louder.

What really went on inside the community that claimed to be the last refuge of truth on earth.

The answers would come slowly through court filings, police investigations, and the voices of those who had finally found the courage to leave.

In two thousand and five, local reporters began publishing stories about the insular world Hawkins had built.

Former members spoke of losing their families, their money, and their sense of self.

That same year, the Texas Department of Child Protective Services received reports alleging that underage girls had been married to older men inside the group, marriages sanctioned under the banner of biblical law.

Officials investigated, but many members refused to speak, citing religious freedom.

Then in two thousand and six, state and federal authorities began looking into the group's finances.

Questions were raised about unpaid taxes, property ownership, and whether members ties were being used for Hawkins' personal benefit.

The compound remained quiet, its gates closed to outsiders, but the image of a self sufficient faith community was giving way to one of a secretive sect operating under its own rules.

In two thousand and eight, hawkins carefully maintained authority faced its greatest test.

He was arrested and charged with bigamy and child sexual abuse following allegations that he had taken multiple spiritual wives, some under age.

Within the community.

The charges sent shockwaves through Abilene and beyond.

For years, local residents had seen the group as eccentric but harmless, a collection of religious separatists clinging to their own interpretation of scripture.

Now, the charismatic man who had claimed to be Yahweh's messenger stood accused of exploiting his followers in the most intimate ways possible.

Court records detailed stories of coercion and grooming.

Women said they were told that resisting marriage arrangements was rebellion against Yahweh himself.

Some were pressured into spiritual unions with men chosen by Hawkins.

Others claimed that the prophet used his position to manipulate them sexually under the guise of divine command.

Hawkins denied everything.

He called the accusations lies from bitter ex members, and insisted that all marriages within the house were lawful and consensual.

He was ultimately acquitted of the most s serious charges, with other cases dropped or reduced, but the damage was done.

The image of the pious teacher had been replaced by that of a man who had turned scripture into a shield.

The legal proceedings brought national attention.

Journalists descended on Abilene filming outside the compound gates, interviewing neighbors and pressing members for comment.

Inside, Hawkins used the scrutiny to tighten his grip.

He told followers that the government and media were agents of Satan, trying to destroy Yahweh's work.

They persecuted the prophets before me, he said in a sermon, and they will persecute the witness of Yahweh now.

The message worked.

Members closed ranks.

Interviews with defectors only deepen their conviction that outsiders couldn't understand the truth.

Hawkins's voice echoed louder than ever across the compound's loud speakers.

His image projected during Sabbath gatherings as he warned of spiritual war for followers.

The prophet was being tested for critics.

The cult was circling the wagons despite the investigations.

The House of Yahweh survived.

Its membership shrank but remained loyal.

The compound expanded modestly, adding new buildings and expanding its publishing operations.

Hawkins continued to preach every week, delivering long sermons full of charts, timelines, and warnings about the coming destruction.

In the following years, new lawsuits emerged, some from former members claiming financial exploitation, others from ex wives alleging that Hawkins had manipulated property and tides for personal gain.

Most cases were settled quietly or dismissed, often due to lack of cooperation from those still inside.

What made the House of Yahweh so durable was in its theology, but its structure.

Hawkins had built a system that sustained itself through fear and faith.

Even after the legal battles, Hawkins remained at the center of everything.

His face was on every publication, his words quoted in every lesson.

Members continued to refer to him as the Overseer, the one through whom Yahweh's voice still spoke.

As the years passed, a growing number of former members began to speak out.

Some had spent decades inside the House before leaving, others had been born there.

Their stories, told through interviews and documentaries, revealed a common theme, the slow erosion of autonomy.

One woman described how her entire life had been dictated by hawkins teachings what to eat, what to wear, who to marry, what to think.

You stop being you, she said, you become part of him.

Another recalled being forced to choose between her family and her faith.

When my husband left, they told me he was damned.

I stayed because I thought Yahweh would kill us all if I didn't.

Psychologists studying the group compared its structure to other high control religious movements, rigid hierarchy, isolation, and a closed belief system that made leaving almost impossible.

By the late twenty tens, Israel, Hawkins was an old man, but his power inside the house remained absolute.

He continued to deliver sermons, sometimes seated, his voice softer but still commanding.

His followers called him the last true prophet, the man who had brought the name of Yahweh back to earth.

Outside observers saw a different story, a community shaped by decades of control, fear, and spiritual dependence.

When Hawkins died in February, twenty twenty one.

The announcement was brief.

The House of Yahweh called it the passing of the Overseer into Yahweh's rest.

There were no public funerals, no acknowledgment of controversy, only promises that his mission would continue through the elders he had trained.

Even in death.

His teachings lived on the sermons he recorded, the books he wrote, and the fear he instilled kept his followers within the walls he built.

Investigations into the group's practices still surface from time to time, but the House of Yahweh endures quieter, more secretive, and still claiming to hold the key to salvation.

Hawkins's prophecies never came true.

His apocalypse never arrived, But in another sense, it did not through nuclear fire, but through the destruction of trust, autonomy, and belief that his followers endured in his name, Part six The Legacy of Yahweh.

When Ysrael Hawkins died in twenty twenty one, the House of Yahweh didn't crumble.

It didn't reform, repent, or fade into history.

It simply adjusted.

The same machinery can turn, guided now by the men he had trained to sustain it outside the compound, Hawkins's ideas continued to influence other fringe religious movements, especially within the Sacred Name in Hebrew roots communities.

Some leaders borrowed his teachings about divine names and end time prophecy, while rejecting his authoritarian structure.

Others quietly adopted his tone, the certainty, the suspicion of outsiders, the framing of obedience as salvation.

This diffusion made the House of Yahweh both less visible and more enduring.

It wasn't just a single church anymore.

It had become a worldview shared by small groups and individuals scattered across the Internet, convinced that the world was on the brink and that only they knew the truth.

In the end, The House of Yahweh stands as a stark example of how belief can become captivity.

It began with a preacher who wanted to restore the Sacred Name of God and became a movement where control was mistaken for holiness.

Hawkins' legacy isn't just the fear he instilled, but the structure he perfected, a theology that turned language, ritual, and prophecy into tools of obedience.

It's a blueprint that has been replicated by countless groups since, some open, some hidden, all sustained by the same equation of faith and fear.

For the followers still inside, Hawkins remains the prophet of the Last Days.

For those who left, he's a warning that when one man claims to hold the only truth, the first thing he takes is your ability to question it.

In the next story, we move from the deserts of Texas to the mountains of Utah, where prophecy took on a different form, not just spoken, but acted upon in blood, a revelation, a murder, and the chilling conviction that God, God had commanded it.

That's next time, m HM.