·S1 E125

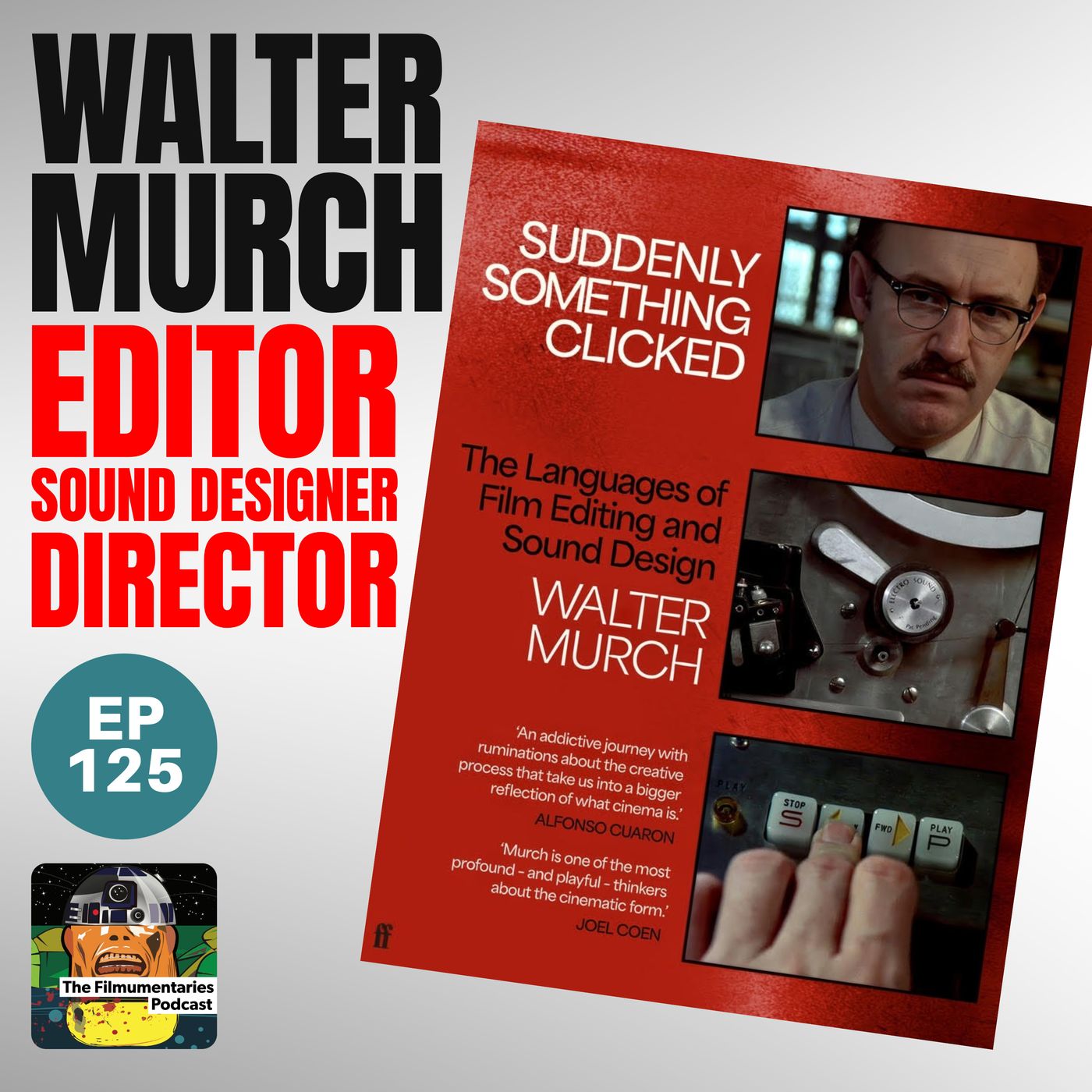

125 - "Suddenly Something Clicked" - With Walter Murch

Episode Transcript

Weirding Way Media.

Speaker 2Hello and welcome to episode one hundred and twenty five of The Film You Mentor's podcast.

I'm Jamie Benning and this episode is a bit of a milestone.

Not only is it the one hundred and twenty fifth episode, but it also marks five year since I launched the podcast.

A huge thank you to all of you who've been listening, sharing and supporting along the way.

And who better to celebrate this milestone with me than the legendary Walter Merch, a returning guest I think the most frequent one him man Doug Weir maybe of the BFI.

Walter is a true philosopher, practitioner of cinema, an Oscar winning editor and sound designer whose curiosity spans from Celli Lloyd to neuroscience.

And this time we speak about his new book Suddenly Something Clicked, which Fabri and Favor were kind enough to send me an early preview copy of thanks to Walter prompting them, and I'm very grateful to Walter and to the folks at Fabri and Favor for that.

The book is actually out on the eighth of May, and as you'd expect, it's full of the kind of insights that only Walter can offer, weaving together practical advice, film history, science, and the subconscious magic of cinema, that stuff that we love so much.

We covered so much ground in this interview.

It's a long one, so strap in.

Speaker 3You know.

Speaker 2We talk about biological editing metaphors to the surreal memory of misidentifying Carl Schultz on a New York street with George Lucas.

Walter even shared some thoughts on AI single shot dramas and how sound can be used most powerfully in a metaphorical sense.

So here's my third conversation with Walter Merch on this special one hundred and twenty fifth episode of the Filming Mentors podcast.

And I'll be back at the end for a bit more jabbering on and for some big news or a little tease of some big news.

Anyway, Awter, I appreciate you joining me again.

It's always great to have you on the podcast.

I think this is the third time, might even be the most.

Are you Have you been here the most out of all of my guests you may have done.

Actually, to me, you're like this philosopher practitioner.

You're a rare combination of technician artist and thinker.

I was trying to kind of trying to work out how best to describe you, and I think that's the best that I've come up with.

You think like a scientist, you kind of edit like a musician, and you write like a philosopher.

I love the new book.

Suddenly something clicked.

What was this sort of feeling behind making this book?

Like obviously link and I continues to kind of resonate with filmmakers and students today, so many people love that.

But what prompted you to return to the page with this book?

Was there a sense that the landscape had changed enough and the thinking had shifted in a way that called for a different kind of reflection.

Speaker 3Yeah, I think you know.

Speaker 4I've been working in film in one form or another for six decades, and the first three decades were analogue, and it was at the end of that period that I wrote In The Blink of an Eye.

So there have been three additional decades now which have been all where I've worked, all digitally.

So that was part of the consideration.

The other one was simply a prompting from Walter Donahue, the film editor at Faber and Faber, and he approached me a number of years ago and said, how about another book?

And I thought sure, and one thing led to another.

Speaker 2You've always had this kind of rare ability, I think to articulate the kind of paradoxes of cinema.

You know, there's sort of certainties and there's mysteries, and in this book you sort of present both those sides of an idea as potentially true.

Do you see this as a kind of central mindset for artists and editors in particular?

Speaker 4Yeah, I mean, cinema is very new in an experience compared to all of the other things that we do.

All of the other arts, the origins are lost in prehistory, and as Bella Balash says, cinema is the only art whose birthday is known to us and been around roughly for the length of one very very long human lifetime one hundred and twenty plus years.

So we're still discovering things about it, as you would expect.

And if you have the kind of the bend of mind, which I guess I do, you can look at it as this grand experiment in human perception.

Speaker 3What is it?

And the to put.

Speaker 4It bluntly, what can we get away with?

In the same sense, that a magician has to know what the magician can get away with in terms of tricking human perception to believe certain things and disbelieve certain other things.

And in that sense, cinema is a kind of magic trick.

And it's appropriate that one of the founders of cinema, George Milias, was a magician, and many others as too.

They were immediately attracted to the medium because of its similarity with magic, and I guess magic is an old art that we've been practicing for I don't you know, let's say ten twenty thousand years.

Speaker 3Who knows what it is?

But yeah, it's also.

Speaker 4That I almost uniquely, maybe not quite, I straddle two different universes in film, in that I'm both a film editor and a sound designer.

In parentheses, I've also written and directed films, so I know I have many kettles on the boil, and that allows me to see things from slightly different perspectives, which I guess encourages that kind of philosophical outlook.

Speaker 2It's funny you mentioned that the magic angle.

One of my most recent guests, Jeff Oaken, is a producer and a VFX supervisor, and he started off as a magician and sort of doesn't see that there's a disconnect between the two.

He sees it as a continuation.

Really, he kind of always regrets that he didn't become a sort of, you know, fully fledged magician performing in front of people.

But in many ways that's why his job entails, because you know, I've spoken to people like Ken Rauston who experimented in v effects with things like, you know, putting a potato on screen instead of a you know, like an asteroid in the Empire strikes back, putting a tennis shoe in a shot when it should have been a spaceship.

It's all about that kind of tricking our subconscious to kind of believe what we're seeing.

And I think all the way you bring you know, sound, you bring your sort of directorial understanding, you bring science, it's just it's just amazing to me how you can go in one chapter from this intensely practical kind of approach to.

Speaker 5Then the philosophical and even then the neurological.

Speaker 2You know, one page might be a hands on tip about editing rhythm, and the next will reference circadic eye movement and the subconscious.

Do you see filmmaking as and especially editing as sitting in that intersection between I guess, craft and cognition.

Speaker 4Yeah, that was one of the pictures that I gave to Walter Donaghue at the beginning of the project, apart from the fact that he initiated the idea of writing the book.

But he said, can you just write a paragraph of what the book will be like?

And I said, it's going to be a twisted rope with three strands in it.

Speaker 3One of them is.

Speaker 4Theory, the other one is practice, and another one would be history.

And I guess in addition to theory, you could you could talk about, you know, the neurology of what's going on.

And that's actually how it turned out to be.

And so I, yes, I jump one thing to another, but that's, you know, as the cowboys used to say, that's the kind of hairpin that I am.

It's also that I'm eighty now approaching eighty two years old, and at that age you also tend to look back on not only your own life, but the life of cinema.

And you know, if we could say that, you know, I am going frequently out on a limb and saying that cinema wasn't invented until the invention of editing, until we understood that you could break up the image into short clips, and then you could reorganize that like a mosaic, mosaic of two dimensions of space and one of time.

The cinema.

Motion photography had been invented, but cinema hadn't been invented.

And that means both the practical nature.

If I mean, imagine the dilemma of trying to make a film in nineteen and four without editing.

You know, it just there's a huge limit to that.

And so it meant that we could break down a screenplay, a scenario into fragments, and then we could reorganize those fragments into the most efficient shooting schedule, taking account of weather and the availability of certain props and actors, and whether it's an interior or an next you know, all of those things.

It made it conceivable to shoot a film of great length and ambition.

And then the editing itself allowed with the invention of continuity editing.

You know, somebody running out of one shot and running into the next shot.

But wait a minute, the second shot was actually photographed before the first shot.

But nobody cares.

You know, and then adding on top of that the I guess what you'd call the coolest Shauvian editing of banging one concept of an image right up against another one and presenting that to an audience as a challenge and a question.

That these are huge advances in the grammar of cinema, and we've just continued to investigate all of those avenues.

Speaker 2Yeah, that that grammar of film, like, as you say in the book, is you know, is once unknown.

Whereas children today, of course grow up kind of intuitively understanding cinematic language, especially now that you know screens are shoved in front of children from a very young age.

Do you think do you think that that language is learned through that exposure or do you lean towards the idea that it's somehow like a pre existing, hardwired thing in our perception.

Speaker 4I think it's it's both.

In early days, Jean Claude Carrier, the French screenwriter, learned from Luis Bounuel, who was a collaborator, that in the early days of cinema in Spain, there had to be someone sitting or standing to one side of the screen who was called an explicador, an explainer, and This was in the days of silent films, and he would provide a running commentary of what are you looking at?

Speaker 5Now?

Speaker 4So this is a this is a close up of somebody, and now we're going to cut to what that person.

Speaker 3Is looking at.

Speaker 4And because the audiences in the very early days of film were people probably in their teens or late twenties, thirties, who knows, but they had grown up without cinema and now they were being exposed to it.

Thirty years later, you didn't have to explain it anymore because the audience had already become from with all of the tropes of cinema.

But I think a more profound level is that many of the much of the grammar of cinema has evolved out of the grammar of dreams and been dreaming who knows for many, many millions of years.

And so in a sense, we are recreating a dreamscape in one form or another when we when we make a film, and we just have to allow the audience the freedom to tap into that.

And it took a while for people to understand that we could do this because the very earliest films, the trope that they were imitating was theatrical that it would be one big, wide shot and you would see people in full figure like you would see them on stage, and they'd be doing things.

And as valuable as that was, it it wasn't really digging into the potentialities of what has ultimately come to be.

Speaker 3Yeah.

Speaker 2I love that recurring thread throughout the book, the kind of biology of cinema and how it links with our biology.

Do you think the part of what makes editing kind of work viscerally is it mirrors something deeper that we have in our biological processes.

Because there's a one point in when there's one chapter where you're linking the kind of scientific with the kind of artistic the DNA and the RNA link.

Speaker 5I won't go too deep into that.

I mean, it's a hell of a chat.

Speaker 2I'd read it a couple of times to fully understand it, but just I always love the way that you strive to link kind of science and art.

Is there something deeper that we have biologically that helps us kind of process edited films efficiently?

Speaker 5Do you think?

Speaker 3Yeah?

Speaker 4I mean, at the first level, it's that what we were just talking about, the grammar of dreams.

Remember that frequently when you dream.

You see yourself in your dream, it's over the shoulder shot, almost literally sometimes, and of course you in real life have never seen yourself in an over the shoulder shot.

You from the moment you wake up, you removed the lens cap of sleep, so to speak, and the single shot, you know, a roving point of view shot for sixteen hours, and then you know you put the lens cap back on you sleep for eight hours.

But dreams are not that.

Dreams are not single point of view stuff, which is all that your whole experience of reality has been a single point of view experience.

But dreams are not that.

We have wide shots, we have over the shoulder shots, we have drone shots, fly shots.

Speaker 3You know, everything that's that.

Speaker 4The chapter you're referring to is something I didn't expect to write.

It's one of the wonderful things about the process is starting out on something and then suddenly getting hijacked by a subject matter and thinking, wait a minute, what's going on here?

And I won't say too much about it, but it's triggered by the discovery within the last couple of decades of a protein complex in the nucleus of every cell on Earth except for bacteria, but you know, pine trees have it, we have it, mushrooms have it.

And there's this protein complex called the spliceosome.

You can kind of see where this is going.

And it takes the copy of the DNA that's made ultimately to make a new protein, and it looks at it and literally says, hmm, there's some bad stuff in here which I have to get rid of, and there's some good stuff, but I can put the good stuff in a better order than it was in the DNA.

And it does that using these what we now call crisper scissors, and it reknits the DNA, which is now called RNA, this copy and pats it on the shoulder and says, off you go.

And this little strand of spaghetti wiggles through the wall of the nucleus out into the larger cell, and then it is in turn attacked, that's the only word I can use, by another protein complex called the ribosome that says, okay, I'm going to make a protein out of this ticker tape.

Basically, it's exactly what's going on, and it does so without the intervention of this spliceosome.

If that copy of the DNA was made.

Without re editing it, nonsense would come out.

And you know, if you look at the original negative of a film, you see the parallels because in the original negative or the digital equivalent of that, there's lots of nonsense in it, you know, stuff that's out of focus, or the clapstick which you don't need, and then run outs and the who knows what else, you know, failed the stunts.

They all have to be purged by the editor in order to make a coherent film.

And that's exactly what's going on inside every one of the trillions of cells in your body as we are doing this interview.

So it's thrilling realization to realize this almost exact similarity.

So how does that happen?

You know, that's another mystery that we're beginning to uncover.

Speaker 5Yeah, it's really is a fascinating concept.

Already kind of blew me away.

Speaker 2I just had to go back to the start of the chapter and start reading it again, because you know, part of my job as an editor is I'm alive editor.

So I'm taking stuff and editing it very quickly to get it back out to air in sports productions and live events and things, and that's something we do like on an instinctive level.

I'm not even that I'm not even intellectualizing it as I'm doing it.

There's just that feeling of what is right and what is wrong.

I love that you that you take those kind of physical moments in editing that have always existed, particularly in the sort of analog age, because I think some people assume that now the analog age is over and we're into the digital age, that you just kind of dismiss all of the kind of things that came before.

Are you talk in the book about physically screening dailies, you know, printing out scripts, annotating scripts, writing your notes and stuff and all of that sort of and even like the posture and the physicality in editing.

Speaker 5Do you think something gets.

Speaker 2Kind of cognitively or creatively lost when we kind of lose these practices and we're replaced by kind of purely digital ones.

Speaker 3Yeah.

Speaker 4I mean we're deep, deep, deep into the digital age now, and we'd be the sort of dip our toe into artificial intelligence.

On where that's going to go.

There's another mystery that will be revealed, but yeah, it's very much the same kind of paradox that you know, in the old days, you had a map, physical piece of paper, and you had to if you were driving somewhere, you had to figure out where you were on that map using coordinates and the things that you saw on the landscape and everything.

Now you just turn on GPS and it tells you what to do.

So I'm glad that I experienced the analog world because it rearranged certain or a arranged certain patterns in my brain that are still there and still active.

But by the same token, when we teach people to drive, we don't teach them Okay, you're going to have to learn how to drive on a model T forward in order to understand where how things.

You know, we just don't do that, and nor.

Speaker 3Should we do it.

Speaker 4It's interesting and curious and stuff can be learned from it, but on a practical level, we live in the GPS world now.

Oh and that's just how it is.

And yeah, and it's not going to go away unless there's some cataclism.

Speaker 3Yeah.

Speaker 2One of my friends said his ex wife was so used to the GPS that she put it on just to go to Tesco's, which was literally turn left, turn right, turn left.

Because we come to rely on these things.

I love that chapter about the Movieola.

I've seen the film as well, which I supported with Howard and yourself.

Speaker 5And Mike Lee in it.

Speaker 2You talk about in the chapter about the Movieola, her name was Movieola, the film that you were kind of surprised at how quickly that muscle memory returned those kind of big physical acts as opposed to these small kind of mouse and keyboard acts.

Do you think how surprised were you, like, and how quickly did it come back?

Was it a matter of just having the kit in front of you and putting your hands on it, or did it take a matter of hours or days even.

Speaker 3It was instant?

Really, it's not the slightest hesitation.

And well, why is that?

Speaker 4My experience, and this is an experience shared by everybody who works in editing, is that if you're working on a film using a certain brand of software, and then the film is over and you go to some island in the South Seas and you all about for a couple of months, and then you come back and oh, here's a new film, and you start using exactly the same piece of software that has not been updated.

It takes a couple of days or a week until you're really comfortable with it because the basic things name but a lot of the more recondite commands have evaporated, whereas with the Moviola system nothing evaporated.

It was all present, And I think that's because of its extreme physicality, and because there's a huge differfference between rewinding a reel and making a cut, whereas digitally, those are just two minor differences in which keystrokes you're using.

Plus fact that in your daily life, when you're not editing a film, you're sending emails and you're on TikTok and you're and you're still doing the same kind of little things with your fingers.

So there's a there's a pollution that enters in where everything gets kind of cross referenced and it's easy to get confused.

Whereas in your daily life back fifty years ago, there was nothing in your experience like rewinding a reel, you know, Plus it made a weird sound and it and some of the stuff you did with chemicals had a certain smelt, So there was a wide cross sensory thing that that really baked in the those impressions.

Speaker 2Yeah, it's interesting how I've really felt a lot of what you were saying links to my world.

I mentioned it earlier, So I'm in what's called in the TV industry and EVS Operator editor.

Speaker 3So.

Speaker 2EVS is a Belgian company that makes these big video servers that can record multiple channels of video.

So it's often used for things like doing replay, building highlights, building packages that go to a very very quickly.

Now, this system has been around since the late nineties and basically stayed the same apart from a few software changes, but the physical nature of it.

There's a remote controller, there's a you know, a jog wheel, and there's a lever for speed, and there's a bunch of buttons to store clips in.

That stayed the same for more than twenty five years and is only now kind of being reinvented in the last couple of years.

It's interesting how all of the systems that have tried to replicate it have always gone down that same route of kind of you know, the jog wheel and the lever and a series of buttons in roughly the same place.

Because experimenting with a mouse and a keyboard doing that job, you don't actually have a sort of visceral understanding of the passage of time that one turn of that jog wheel takes and you don't have the there's a clutch built into it as well, so you can't play it.

Speaker 5And rewind it at the same time, so you hear a click.

Speaker 2So when you queue it up at some point and let's say roll of replay, it clicks and you get this little kind of you know, tangible visceral feedback.

Some of the competitors didn't include that in the system, and it wasn't until we realize that it wasn't there how important.

It was just some of those little key indicators.

And we're probably never going to go to a system where we have a mouse and a keyboard to do those operations because you need those kind of big physical movements to kind of I don't know, it just becomes natural.

I don't ever find using a mouse and a keyboard natural as such.

Yeah, in some interesting parallels to my world, you also, and we kind of touched it already.

Speaker 5You evoke that beautiful sort of.

Speaker 2Image of letting things percolate, that moment in a screening where you, you know, make a note and then have some distance to help sort of clarify.

You seem to have these strategies to kind of deliberately not solve something too quickly, which I kind of admire in this more day where you know, we're responding to text messages instantly and I think emails are checked within nine seconds of them arriving on average.

Is that something that you always strive to do to allow yourself to sort of have these subconscious influences on your work.

Speaker 4Sure, but it also goes to the nature of how films are most films dot, which is in as we were saying earlier, they're shot in this fragmented way where maybe a week into shooting, there is a day where they shoot the beginning of them in the end of the film, and so you have to receive that information and imagine how that's going to work, even though all of the intermediate material has not been filmed yet, and so you have many things on the.

Speaker 3Boil which are all which are.

Speaker 4Influencing other and will continue to influence each other in this very extended process, very much unlike what the kind of work that you're doing, which is this live theater sort of experience.

This is, you know, if the film is being shot over sixteen weeks or in the case of apocalypse now over two hundred and fifty six days.

You have to kind of accommodate that that slowness into the way that you that you think.

Speaker 2How do you think though, that we can give this, you know, afford this to younger editors, given a the kind of world that we live in in terms of you know, the kind of you know, machine gun approach of information into our faces from our phones, but also schedules these days, schedules are seem to be a lot tighter and budgets seemed to be a lot smaller.

Had care can we kind of encourage people to make that kind of space.

Speaker 4I don't know, it's personality also, so and things were changing, uh, you know the how what was the shooting process on adolescence?

You know, well that's a completely different thing where at least if going with what they say, they did a huge number of rehearsals of each scene, and then on the day of shooting or the days of shooting, they said go and for one hour they shot the movie.

Every minute of shooting is a minute in the life of the film.

And then at the end of that they looked at whatever it was, you know, ten or ten or twelve takes and they said that's the one, and that's the one.

Speaker 3That we saw that.

Speaker 4That's a completely different process.

And somewhere in between is the process that Sam Mendus used on nineteen seventeen.

It gives you the impression that it's all continuously one shot, but it was in fact broken down into a series of shots that were then digitally knitted together to look like it's continuous.

So it's a moving target.

Speaker 3It's a.

Speaker 2What's your thoughts on Adolescence?

And I guess to certain extent nineteen seventeen in terms of what a lack of editing does to our subconscious and how we can kind of read the situation.

I mean, my experience watching Adolescence is by the time you reached the finale and he's there in his son's bedroom holding his teddy bear, I was kind of in pieces.

You know, it really to affect me emotionally because you really felt like you'd been part of their lives for that for that period of time, and it had that same thing that you know a lingering shot might do, where you just start to feel a bit uncomfortable and you know you just feel like, yeah, what's your take on adolescence.

Speaker 4Do you think no truth in advertising here?

I haven't seen adolescence, so just responding to the phenomenon of it and of other films that present a continuous reality.

It is great, I imagine for the actors because they are in control of things to an extent that they certainly are not when we shoot film in in the mosaic pattern where you know we're shooting the end of the film in the beginning of the film on the same day, and what emotional resources does that draw out of the out of the actor.

So on that level, it's it's good.

I think it as a way of doing things, it's certainly valid.

I'm giving a presentation in Paris at the Cinema Tech and they asked for a title, and I said, you know, it's in French, but I said, cinema without editing?

Is it cinema?

So it's a provocative answer, and what I plan on saying the first words out of my mouth are, of course it's cinema.

But what is a cinema that doesn't allow you to have the cut in Lawrence of Arabia from the match to the sunrise.

Now that is that's a dream cut and the difference I guess with adolescence is that it is not a dream in terms of those leaps of logic and surrealistic impositions that happen in dreams happen in cinema.

They happen in Lawrence of Arabia.

And if you could say a magic wand and say okay, from now on, all films will be shot like adolescents, we would be cutting off some part of our anatomy.

Do not have the ability to cut from the match to the sunrise.

Speaker 2It's interesting that it's still adolescent, still has to conform to many of the things we expect from cinema in terms of where the camera is positioned or where it settles, you know, or the transition from one to the other and over the shoulder shot in a conversation rather than cutting.

Speaker 5Of course, it has.

Speaker 2To move to show that and kind of changes the dynamic between the two individuals talking in that particular episode that's in just one room.

We're never going to get away from those kind of those tropes in cinema, even if there isn't editing.

I'm sure, and I like it as an experiment.

I just don't necessarily see that it kind of fulfills me artistically.

Speaker 3I don't.

Speaker 2I enjoyed watching it.

I thought it was interesting, but it seems like anomaly rather than something the points to a future.

Speaker 4Let's say, yeah, I would tend to agree in that sense.

It's different but similar to three D.

For a while in two thousand and nine, we were thinking, all cinema will now be three D.

Speaker 3Well, what happened?

You know?

Speaker 4That isn't the case.

But there's a chapter or a heading in the book that says, the cinematic cut cleaves the stone of time.

And that's what cinema does with the invention of editing, is that time itself becomes manipulatable, and what adolescence does is deny that.

It says no.

The thirtieth minute of this film is exactly thirty minutes from the beginning of the film, and it's it's valuable because it's this twilight one between the theatrical experience and the cinematic experience.

Francis Coppola wrote a book called Live Cinema number of years ago that gets into this exact area, and it's some area that he was very interested in.

Speaker 2Do you know that that was the same company that I talked about earlier that I work with Evs.

He did did a white paper with DVS making a live a live show like you know, walking continuously through one door.

He did some interesting things in that where he would do a rehearsal where somebody had to open a window and shout something out the window, but before they rolled, he'd go and lock the window to kind of invocus, sort of instinctive response to the situation.

Speaker 5So are you going to see adolescence before you give your talk in Paris?

Speaker 3Yes, I will see it.

Yeah.

Speaker 2You mentioned quite early on in the book about this particular moment where you're walking the streets of New York with George Lucas, somebody who'd been friends with for many years, and seeing what you thought was an old colleague of yours, Carl Schultz, and then realizing it was not Carl, and then seeing Carl later on so shortly after that, and it seems to be, you know, this perfect metaphor for cinema's relationship to you know, expectation and misdirection.

As an editor, are you, I guess you're always constantly managing what the audience expects to see versus what they're actually seeing.

Speaker 5Was that kind of a bit of an epiphany moment for.

Speaker 4You, Yes, Melby, it was a mutual delusion in the sub I was walking down Seventh Avenue in New York in nineteen seventy seven, shortly after Star Wars had come out.

I was in New York previewing Fred Zinneman's film Julia, which we were in the process of walking and ran into George at We were at the same hotel, and we were ambling down Seventh Avenue, and I looked ahead and saw, Look, it's Carl Schultz, who was the general manager at Zeotrope four years five years earlier, and he had had that job for six months or something, and in the intervening years there was probably no reason for George or I, either of us to think of him.

But we both looked and said, yes, that's Carl, and we maintained that illusion until the kind of the last possible minute, when he was only six feet or eight feet away from us, when he suddenly morphed into not Carl.

All of the key parameters, his his shirt, the kind of shirt that he wore, the way he walked, his beard, everything fit until he got so close that the details of this real person overwhelmed the details that we were projecting onto him.

There are many analogies to make with the process of filmmaking.

Is that great quote from John Houston that says the real projectors are the eyes and ears of the audience, and that the film itself is just a pretext for that projection to take place.

And in an ideal sense, I guess we as editors want to control and anticipate the reactions of the audience, but not too much in advance, or not too little in advance it Ideally it would be to kind of get them to have a sustained deja vu experience where they're feeling, I don't know what's going to happen next, and then it happens and they said, of course that's what.

Speaker 3Had to happen, you know.

Speaker 4So there's a mixture of surprise and self evidence that you know, if you have too much of either of those, then the audience gets bored.

If everything is surprising, it's like chaos.

If everything is self evident, it's like why am I watching this?

Speaker 3Yeah?

Speaker 5And it's a soap opera.

Speaker 2The first time I had that sort of understanding of perception versus reality, I was in my twenties and I was walking up Victoria Street in London, and I was waiting at a crossing with a load of people on one side, load of people on the other side, and of course nobody had pushed the button to actually activate the crossing lights.

But I remember looking across the road and I saw this school kid in a little cat and a blazer and shorts and kind of shiny pattern leather shoes.

Speaker 5And I looked at my watch, thinking, oh, yeah, it's half three already.

Speaker 2You know, the day I kind of got away from it, all scores are checking out, and just at that moment, a bus turned the corner heading down horse Ferry Road and it's kind of wiped the frame and instead of the kid, there was this like ancient Chinese woman standing exactly where this kid had been, wearing a little hat and a blazer and shorts and little pat and shoes, and I just I actually sort of staggered backwards.

I couldn't believe that my mind had tricked me into thinking this was a Schul kid.

But in the same way that you know, you saw the gate and the shirt of car, I saw what I assumed was a Schul kid because it was that time.

It kind of fit with the parameters of where I was and really changed my sort of understanding of how we can be falled and how our vision really is perception, it's not you know, it's not accurate, let's say.

And of course that lends itself to many the things that you've done in the industry in terms of, you know, trying to trying to kind of misdirect people and change expectations.

Speaker 5Not a question, just a statement.

Speaker 4The weird thing about the Carl experience is that I wouldn't have remembered any of this with the exception that George and I walked for another block and then we turned right and bumped into the real Carl Schultz.

It was so much of a hole in one that you kind of accepted it as well.

Of course this had to happen, Yeah, Carl, we were just thinking about you.

So no, had we turned left instead of right, we wouldn't have bumped into Carl, and I wouldn't be retelling this story, let alone writing it as the first chapter of a book.

Speaker 2Yeah, it's crazy that even the fact that you and George bumped into each other at that point in a way, but we accept those kind of coincidences, but then having this shared experience of both thinking it was Carl and then seeing Carl.

Speaker 5It just kind of boggles the mind.

Speaker 2There is there are many mysteries that we still don't understand, and that's what I've always liked about your writing as well.

Speaker 5You know, you can have, like I said earlier.

Speaker 2Like a practical tip that works for you, but you also kind of acknowledge that a lot of this is still mysterious.

You know, we can continue to try and pin these things down, but we still have to acknowledge that, you know, we're probably not going to reach a point where we can pin everything.

Speaker 3Down, Thank goodness.

Speaker 5Yeah.

Absolutely.

Speaker 2I also like that early sort of mention in the book about the fresco versus all painting analogy analogue versus digital.

It really stuck with me.

The fresco is sort of being you know, immediate and irreversible to a certain extent, but then oil paintings being more adjustable.

Do you do you think that that sort of flexibility that we have with digital now has improved the storytelling or is it sort of weakened our instincts?

Speaker 4Hm, hard to say, hard to say it.

I mean, in comparison of of course, even mechanical analog editing.

There was a lot of the oil painting in that in that you could choose things.

It was it was more awkward than it is now, and it took time to work it out and to physically do it.

But you know, we could swap out shots, we could make Reel two become real one.

You know, it's all relative to the film that you're working on, I think.

But we're, as I said, we're so we're now three decades in digital filmmaking and we're at the brink of this new experience with AI, which is both a continuation of digital it's enabled obviously by by digitization, but at the same time, we're going to find surprises in there that we haven't anticipated.

You you could, He's obviously with AI, you can make a film without any edits in it.

Speaker 3Oh is that good?

You know?

Who knows?

Yeah?

Speaker 2That's my kind of worry about AI in a way is that it kind of removes that spontaneity that we have.

Speaker 5As humans.

Speaker 2And you know, I spoke to a couple of people on this podcast who had very kind of different views.

Not necessarily a question about AI, but one of the designers Neilo Rhodis Jamiro who worked with Lucas, sort of talks about, you know, there's nothing more daunting than that white page and you know, a pencil or in his case of pen in his hand and just having to draw a form and just letting the form kind of mutate into something.

Whereas then I spoke to Nathan Crowley's production design who just won the Oscar for Wicked.

He uses AI to kind of leapfrog that iterative process to get to a place quicker.

But in a way, I guess he kind of questions whether he's losing something by the by leap frogging.

But I guess ultimately a lot of it comes down to these days, as I mentioned earlier, budget and schedule and all of those things.

But there's no right or wrong way to do it, I guess.

But I do wonder if even if AI could mimic spontaneity.

I don't know if we even accept it as real.

I don't know, there's something there's still that Uncanny Valley thing going on.

Speaker 4Yeh, the great But at the same time, the awkward thing about filmmaking is that it's such a collaborative art.

Every one of the people who works on a film, particularly the heads of departments, has a vision, some of which is articulate, some of which is not of what this film is going to look like and feel like, and those are frequently at slight odds with the vision of the director.

More power to it, because what that does, if harnessed correctly, is those slight differences add facets to the diamond of the film, which allows the light of consciousness to bounce around in it.

Because they're all slightly contradictory.

But that's like life, if it's all the product of a single human mind.

There's a kind of airlessness that the danger of that is this conceptual airlessness, which is this is everything that I conceived exactly the way that I wanted it achieve, you know.

On the other hand, that's kind of the way digital animation is done.

In a sense, every Pick and a Pixar film has been consciously or unconsciously blessed, you know, that's right, and to the extent that in later versions they've tried to introduce mistakes, you know, artificial stakes into the process.

But there's nothing like the reality of a conflict between the vision of the production designer and the vision of the director, and the vision of the cinematographer, and the and the vision of the actor, you know, all kind of swirling around.

A great example of that is in Godfather, when when Gordie Willis saw the makeup that was being done, he to by his own admission, he said, this is a disaster.

You know, how can I.

Speaker 3Work with this?

Speaker 4And his solution was to light from above so that the eyes were cast into shadow.

I mean, you can see this brilliantly in the opening scenes of The Godfather in the office, right.

And when al Pacino saw this lighting, he didn't have much experience in film at that point, and he said, what is this weird lighting?

But that choice of that weird lighting gave him an insight into his character, which is, my character is being followed by a spotlight, the spotlight of fate from above, and I'm constantly, as a character trying to get out of that spotlight.

I don't want to be part of this family, you know, and spotlight would find him again, and then he'd have to find a way to get away from it again, and it would find him again, until finally he got into the match, you know, and he became the godfather, you know, rather than you.

He completely failed at getting out of the family.

But you know, it's almost one hundred and eighty degree opposite.

He became who he was trying to escape.

That was all an interaction of the makeup choices, the lighting choices, and the acting choices.

But those were three different people.

Dick Smith did the maker, Brody Willis did the photography, and al Pacino was the actor.

Speaker 2Yeah, we're not going to have that when we just write a text prompt.

There is a chapter in the book that isn't written by you, and it's Paul hersh Forber guests on this podcast as well.

Had a great time chatting to Paul about the Droid Olympics, and that's something I only found out about recently.

Speaker 5Relatively recently.

Speaker 2I think it was in Michael Rubin's book Droid Maker, where he talks about Lucas's work and kind of rare for editors to be well a together, be and outside.

They sounded like some fun times that you had there doing those events.

Speaker 4It was triggered by the fact that my wife had just put on a Jim Kanna with kids riding horses and you know, doing all these slightly dangerous and slightly silly things and getting blue ribbons as a result.

And I was editing Apocalypse at the time, this is nineteen seventy eight, and my assistant, who ninety percent of the time, was reconforming daily, which is about mind numbing and experience as possible, but you have to pay great attention.

And to relieve his frustration, he somehow got hold of a superhero character at the time called Stretch, who was a plastic plastic man tybole person, and he had put wire on stretches hands and feet and then lamped Stretch into the synchronizing machine, rewinding back and forth.

And I said, Steve, what are you doing?

And he said, Stretch has to suffer.

And that's when I thought, Okay, these guys need some fresh air.

So we set up out of our house in the country just north of San Francisco, the Droid de Catalon, the Droid Olympics.

We called it Droid because that's what all of the editorial assistants on Apocalypse called themselves, because they felt they were just robots doing this, reconforming all the time.

And so how fast can you do a splice?

How fast can you rewind a thousand feet.

How accurate is your sense of time to blindfolded stop a movieola exactly forty five feet from the beginning, You know, those kinds of things, and you know, everyone got a medal who won, and then there was a super you know, got the most points.

So and we did it three times, I think, the seventy eight and eighty two and then eighty seven, I think.

But it's kind of like the what happens in lumberjacking contests where you do all of these old type lumberjack events that nobody does anymore.

They're very visual and visceral experiences that are just didn't there denied us in the digital world.

Speaker 5Yeah, that was going to be my next question.

Speaker 2You know, what is the how can we get editors outside and kind of a chance to kind of vent?

Speaker 5Maybe there isn't an answer to that.

Speaker 2In part two of the book, you talk about sound design and how sound went from this kind of you know, powerful king in its inception in cinema to often being forgotten about because there's a sort of I thought that it's inevitable and therefore it's an afterthought.

Do you think that you know cinema during that transition kind of suffered in that regard as to where and how film ends up in a sound ends up in a film.

Speaker 4Yeah, it was particularly the case when I started working professionally because of something that this was in the late sixties, early seventies, but because of something that had happened in the early fifties.

The sound was still reeling from that experience, which was the transition from optical to magnetic sound.

And in nineteen fifty two, let's say, when that transition was in full force, sound had been around for twenty five years, I think the math is correct, from twenty seven to yeah, forty seven to fifty two, and so many of the guys who started film sound were near retirement age, and they looked at magnetic sound and they said, I'm out of here, you know, I don't want to make this leap.

And so there was a crisis.

This is in Hollywood, where doors that had been formally firmly closed in terms of union representation were suddenly open.

Anyone who wants to can become a sound editor now because of all of this mass retirement.

And so a lot of people went into film sound.

Not everyone by any means, but a lot went in simply to get a union job, which was like a miracle opening up.

And then when the roster had been completed, there was the clanging of the door shut and a lot of people realized, oh, I don't really I'm not really interested in sound.

I just wanted a regular job.

And so there was a period where sound was kind of low on.

Speaker 3The totem pole.

As a result.

It was just.

Speaker 4Something that had to be done, but very few people put a lot of heart and soul into it, comparatively speaking.

And by the early seventh is that, in turn was beginning to change, I guess, and I represented the next generation of people who really thought sound could be great, that it was an unexplored area, and you know, we stormed the barricades trying to force it to be better than it was.

And then thankfully along came Dolby and made this technical leap, so that the experience in the nineteen fifties, say, was that unless you were going to a big road show of a film with seventy milimeters with magnetic sound, you were listening to films that sounded exactly the same as Gone with the Wind in nineteen thirty nine, there had been no technical advance, and then suddenly.

Speaker 3With Dolby there was this leap.

Speaker 4But in the fifties you could listen to an LP and hear the full sonic range from whatever it was thousand forty cycles per second to sixteen thousand.

But you go to the cinema and you couldn't hear anything more than eight thousand cycles, and Dolby fixed that, Thank goodness.

Speaker 2I often think with sound.

I was thinking this as I was reading part of the Sound chapter this morning.

Similar to the way visual effects has tried to replicate life and be photorealistic, it feels to me sometimes that sound is thought of in the same way by some practitioners, and that they're not really using sound to its fullest extent, you know, in terms of its power of using it in a metaphorical way to invoke, like, you know, certain emotional response.

Rather, they seem to be layering sounds to such an extent that we just end up with that sort of muddled confusion that we have in life, where we you know, there are footsteps and there's a plane going over and a bus going by, and but do you feel that sometimes that that is forgotten about the kind of way we can use sound in a metaphorical sense to you know, evoke those emotional responses above.

Speaker 4The film reviewer presently he was at the La Times, he's at the New Yorker.

Now we're getting his first name, David Chang.

Chang something he said, a film can be so realistic that you don't believe a moment of it.

That's I think the essence of what you're talking about.

And it just goes back to the dreamscape that we were talking about earlier, that in dreams, the thing that makes dreams memorable is what did.

Speaker 3What was going on there?

Yeah, this is weird.

Speaker 4And so what I try to do in sound is used, as you put it, used sound metaphorically, which is to say, you're looking at an image and the sound you're hearing does not seem naturally to go with that image, and so it poses a question to the audience, and the person in sitting in the audience consciously or unconsciously completes the circle.

It's kind of a gestalt moment where what's implied is rendered complete by the imagination of the viewer.

The miracle and greatness of that is that everyone will complete that question in a slightly different way, and then they project that completion onto the screen, imagining that it comes from the screen, but it's not.

It's kind of like us seeing Carl Schultz.

We project Karl onto this screen of reality anyway.

But as a result of that, the film talks to you in a way that seems very personal, because you have projected yourself into the film to resolve certain questions that the film is posing to you, either editorially or in terms of script or in terms of the acting performance, and in terms of sound.

I mean, the classic example for me was the roaring of the train in Godfather.

Was not in the screenplay, it wasn't in the book.

It came about as the result of the fact that Francis and Nino Rota had decided they were going to have a big music cue after the killing, so they didn't want any music leading up to it, no suspense music.

But the scene is in a foreign language, a third of it with no subtitles, so it needs something.

And because of where I grew up in New York, I knew that the Bronx had these elevated trains.

So let's put the sound of an elevated train.

It must be one in that neighborhood, and it comes and goes and comes and goes and builds in intensity until it starts screeching in the moments before Michael pulls out the gun and shoots Slotso but the audience, some people in the audience don't even hear that sound, you know, they interpret it as what's going on inside Michael's head making up He's trying to decide should I really kill this person at point blank range.

One of the nice, mostly unremarked twists is that Clemenza, in a couple of scenes previous, said, once you've got then come out of the bathroom blasting.

In other words, he said, as soon as you come out, start shooting.

Speaker 3But Michael doesn't, you.

Speaker 4Know, he comes out, stands there for a few seconds and then comes and sits down.

And so the question the audience is asking is is he not going to do what's going on?

And then the sound comes in and it intensifies the moment.

Anyway, that's a metaphorical sound that is based in some reality.

Speaker 2Yeah, And as I think I heard you say in a lecture in North London once, and I think we might have talked about it previously in a sort of Carl Schultz coincidence, there was actually an l train right outside that shooting location as well.

Speaker 3Right, I got a great email.

Speaker 4From the sound recordist on Godfather, who said he went to see the film in Minnesota.

He was visiting relatives and he heard the sound of the train and he thought, w tf.

I there was the train, and I did everything to get rid of the train.

Speaker 3What's happening?

Speaker 4And then of course he began to realize with the rising intensity that it was put.

Speaker 3There on purpose.

Speaker 4But yeah, as it turns out that they're just outside the door of this real restaurant was an elevated train track, and which I didn't know.

You know, it's a real call, short moment, and in the shooting of the scene, they were doing everything they could to try to squeeze in dialogue between the passing of the train.

Speaker 5Amazing.

Speaker 2I love just how all the confluence of all these different things coming together to make that what it is.

Speaker 5This is a bit of a weird assign.

Speaker 2This is I spoke to a live television sound supervisor recently, and usually when I chat to them, you know, I asked them about what kind of sound set up do they have at home?

And is there a favorite cinema of there as they like to go to.

But this particular guy said, I've never understood surround sound.

Cinemaon TV is a flat medium.

What are your thoughts on what surround sound actually does to the audience?

So I can go back armed with a good answer to that kind of flip and throwaway comment.

Speaker 4I mean, it was particularly pungent aromatic question when we were fixing Apocalypse Now because none of us working on the film had ever worked in stereo, let alone stereo with surround alone surround that was split stereophonically.

We were creating what is now known as five point one sound, but we had all worked in mono, so we were simultaneously excited and petrified by the working in this new format.

So we came up with a list of dues and don'ts.

Don't do this, try to do this.

One of the don'ts is don't put any dialogue into the surrounds unless the scene is completely chaotic, such as the Playboy Bunny concert.

You know, when that gets intense, then there some dialogue that creeps in.

You can put a little reverb of the dialogue into the surrounds.

Those kind of decisions.

But as an example, if I this is just personal.

If I have a sound that is fading in is going to become loud.

When it fades in, I put it.

I keep it in the center as mono, because center is a neutral place.

You know, none of the spatial neurons are being activated as it gets louder, and this is just a creative intuitive moment.

At a certain point, I will put it where it should be in terms of the image to the left, say, or left back or something.

And then as it gets even louder still, then I will move it in the direction of whatever the sound might be doing.

And then as it fades out, I bring it back to the center again, which is this neutral point, and paid it out.

So those kind of things are happening.

There's a weird example of this where I kept running into it and then it really became pointed in.

There's a scene in Cold Mountain.

They're having a party and Stowbroad is playing the violin and he's moving around the scene and people are talking and playing an instrument at the same time, And what worked was to put the dialogue only in the center, even though the person is on the left side of the screen, so the dialogue is coming out of the center only, but the sound of the violin is moving left and right depending on where he's going.

So you get this complete paradox moment where the violin and Stowbrod is over on the left hand side, the violin is on the left, but his dialogue is coming out of the center, and it seems absolutely normal.

In fact, it would seem wrong if we put his dialogue over there.

Speaker 3So what's going on?

Speaker 4I think it's because music is experienced directly.

It's not a code that you have to break.

It's a sound pure in itself, whereas dialogue has to go through the language part of your brain to quote it what is he saying and then you understand it.

But that's a very complex pattern.

And so basically the brain says, as far as dialogue goes, I will ascribe source to where the image is because it's too complicated for me to decode the language and assign sources to it.

So those kind of stuff, and if you just use those kind of decisions and extend them into the complexity of surround it begins to get at the nature of the craziness of this medium.

But I'm slightly suspicious that you know, I'm eighty two s or or almost atmost to me is a bridge too far, you know, because we are looking at the screen.

It is even in three D.

It's two dimensional in the sense that it's they were in a box and one wall of that box is luminous, so we're oriented that way, and you have to be careful about pulling attention to the behind.

There's a great cartoon in the book at the beginning of the sound thing, where there's a personal screening in the audience around looking what screaming at.

Of course nobody does that when watching movies, unless the scream is coming from the surround it would turn around.

But then that just reminds you that you're in a box watching a painted wall, you know, and you don't have to happen.

You want people to be immersed in the world of the film.

Speaker 2So my colleague Dave was kind of right in a certain way.

I guess I'll play your answer to that.

Speaker 5Today.

Speaker 2I was delighted to read that this is there's going to be a second volume of the book, and you talk about can cinema solve a problems?

What can we expect in volume two?

Is it going to have the same title and just be volume two or is there a new title of the book.

Speaker 4Well, actually, the original conception, which is still to be revealed, that it was three volumes.

Suddenly something clicked.

The second volume is focused on production, which is to say, writing, I include that in the process, writing, casting, directing, And there's a section on my own experiences directing Return to Oz and what was involved in making that film.

The fact that I was fired six weeks into production and then rehired a few days later, and why did that happen?

And how did I Houdini like escape from eternal punishment.

So that's that's volume two.

Let's say three gets into even some more philosophical things, which is where are we going with cinema?

The fact that actually twenty twenty five is the two hundredth anniversary of motion pictures in the sense that the Thelma trope, which was this simple two image device, was invented in eighteen twenty five, and then the ootrope, phoenixistoscope, they were they came along in the eighteen thirties, and so here we are two hundred years later, are are we Are we going to continue to evolve or you know, or are we going to be diverted into this artificial intelligence path, and how does how does cinema deal with the fact that among all the arts, it's the one that accesses more parts of the brain than any of the other arts, that, because of its visceral nature using image and sound, can directly address what's called the brain stem part of us, the instant reaction to something, the so called reptilian part of our behavior, fight or flight.

The middle part of the brain, which is mainly mammalian in evolution, is the fact that we suckle our young and we educate our young, some more than others, but that's a notable difference from most reptiles, who simply have babies and let them go out into the world.

So the emotional component of mammals is very different than reptiles, and that's part of us obviously, and can directly access the emotional part.

It has to, really in order to have an effect.

But then there's this other part, which is the logical part, the neocortex, the little linguistic part of our brain that says, wait a minute, that doesn't make sense.

He wouldn't have gone, he wouldn't have grabbed the knife before seeing her, because she knows that you know, all of those kind of if then clauses where you can lose an audience because of a logical contradiction.

So there's a plea I guess to say film at its maximum, pushed to its fullest, it can in a symphonic way or a novelistic way.

It can simultaneously talk to and choreograph the reactions from all these different parts of the brain.

And most of the time, when we're in our ordinary life, those three parts of the rain or talking to each other, but they're usually in some kind of conflict.

I don't know what came over me, Why did I do that?

Speaker 5You know kind of things.

Speaker 4But a film allows for the duration of the film, if it's a well made film, and if it has ambition, it can choreograph those three different areas and we come out of the film transformed in a way because of that experience.

It's similar to you know, what happens in a well written symphonic situation any piece of music, but symphony is relevant because so many people are involved.

You don't want all of the instruments to be playing the same thing all of the time.

You want the violins to be having one sort of discussion, and the Woodwinds are saying yes, but something else.

The Timpanie are doing something else yet again.

Speaker 3And that's.

Speaker 4You know, the wonderful thing about those experiences when they work, is that bilogue that's going on.

There's a great line in the book I forget which chapter it's in, where Mike Nichols says, when I go to a party, what's interesting to me is to watch people.

They're doing one thing, they're saying something else, and they're thinking something else yet again.

And film has the ability to choreograph that that.

You can have an actor say I love you to the girl, but he says it in a way that says, I don't really love you.

It can be photographed in a way that says, but he really does.

You get this interweaving of these three things and those areas are just very provocative and exciting and reveal the depth and possibilities of cinema when it's pushed.

Speaker 3To the wall.

Speaker 4I mean not in a positive sense, straining every sinew to deliver what cinema can deliver at its best, and by no means should all cinema be that way.

And it would be intolerable if every cinematic experience was like that, you want the equivalent of chopin preludes in cinema, where it's just, you know, we're examining one thing and it's my dinner with Andrea or whatever, God bless it.

You know, it's a smorgas board of different things.

But at the same time, what I was trying to investigate is just answer the question what is it that it can deliver like no other art form.

And certainly, you know Richard Wagner in Opera had this idea of the total artwork in German gesampt Kunstbach.

I'm sure had he been born one hundred years later, he would have been a filmmaker.

There's another chapter, a series of chapters.

Actually, again I was very surprised to be writing about this, but it happened.

Speaker 3Which was.

Speaker 4The uncanny persistence of framing that puts the eyes of the actors in close up along the golden ratio of the vertical dimension of the frame.

And I try to demonstrate that this is in fact true and has been true for at least one hundred years, if not longer, and then try to answer the question why is this?

And what I came up with is that it has to do with the main features of the human face, begging in a golden ratio, that the line through the eyes compared to the line through the nose compared to the line through the lips, that is a golden ratio.

And it also applies to the hairline and the chin.

So anyway, I have to get those kind of areas.

Speaker 2What I like about the book as well is that you've got these QR codes throughout which are links to some of the videos that you've made and clips from things that you're talking about, so we're able to sort of read your understanding, your explanations, but then see them have a visual representation of them.

I really enjoyed the chapter in which talk about rearranging the conversation and just what scenes were missing, which one shot, and how you had to reconfigure the film to kind of make sense of it.

Speaker 5Is that something you're going to continue through the next few villions?

Speaker 3The other everything is written, it's just waiting to be published.

Speaker 5Okay, okay, cool?

Speaker 2Well, an any film nerd friends of mine listening that have birthdays coming up soon, this is going to be this is going to be their gift.

I love the book Walter, and I really appreciate you know you and what you do, and I really appreciate you giving your time today to talk to me about the new book.

Speaker 3Wait absolutely, thank all.

Was a pleasure to talk to you, Jamie.

Speaker 5Thanks Walter.

Speaker 2That was the brilliant Walter merch and what a pleasure it is every single time I get to chat to him.

I'm really grateful to Favor and Favor for the early copy of Suddenly Something Clicked, which, as I mentioned, is out on the eighth of May twenty twenty five.

If you're a film lover or just fascinated by how we see and hear cinema, I highly recommend picking it up.

Speaker 5It's fantastic.

Speaker 2I finished it and then I just started it again, and we've got more volumes to come, which is exciting news.

Thanks for joining me again on this one hundred and twenty fifth episode and for five years of film youmentaries.

Whether you've listened to a handful of episodes or you've been here since the start, I truly appreciate it, and you know, it's been a genuine joy to share these behind the scenes stories with you, and there's plenty more to come.

Please support the podcast.

I need at least one hundred more patrons of you to do so to make this financially viable.

Otherwise it's just a hobby that stops me from spending time with my family.

Patreon dot com forward slash Jamie Benning.

I hope you enjoyed the recent bonus episodes with Vicky Sampson talking about the day some vital return of the Jedi reels got stolen from her car, and also the bonus episodes from Rachel Pearson reporting some news from the floor of Star Wars Celebration Tokyo.

So the next location for Star Wars Celebration has been announced as La and it's going to be the fiftieth anniversary of the Star Wars or Star Wars as I call it.

Maybe I'll go, Maybe I'll find a way of doing something for ILM again.

That would be fantastic.

I'd love to do that another panel maybe or maybe present something we'll see.

But thank you to both those amazing women, Vicki and Rachel for their contributions on those bonus episodes.

Okay, the big news that I promised at the start of the episode here you may have already seen that an original nineteen seventy seven die transfer print of Star Wars is being screened here in London at the BFI.

It's on the twelfth of June, and tickets can be bought on the following dates, so listen up.

So if you're a BFI patron, which will probably not, that's Tuesday, the sixth of May, from twelve o'clock you can buy tickets.

If you're a BFI member, it's Wednesday, the seventh of May, from midday.

I would say, get a membership.

It's not that expensive and it will mean you've got a much better chance of getting the tickets.

They're going to go very very quickly, I'm sure.

So yeah, BFI members Wednesday, the seventh of May, and then the general sale is Friday, the ninth of May, from midday.

By then, I would imagine that quite a lot of tickets will have gone.

So and I'm very pleased to say that my friend and previous podcast guest Doug Weir, we're going to do something related, is all I'll say.

On the same day as the screening at the BFI.

We're just finalizing things, so there'll be more details in the coming days and weeks, but it's exciting as always.

You can find more info about my films, the podcast, and anything else film mementitories at filmmentaries dot com.

In fact, you can sign up there for a monthly newsletter so that you don't miss a thing.

I'll be back with another great guest on the thirteenth of May.

In the meantime, enjoy Light in Magic Season two.

That's just come out this week and it's fantastic.

It's only three episodes, but Joe Johnston and the team have done a great job.

I ended up sending Joe an email just to thank him, and also to Rob Coleman as well to say it was great to see him featured so heavily.

I spoke to Rob RECs for an article that I'm currently writing for ILM.

Really good guy, really really good energy and just a sweet sweet man as well, and also super talented of course Autogum.

As always, lots of interviews lined up, hopefully trying to get a few more bonus episodes going this year as well.

In the meantime, take care thanks again for listening.

Five more years, five more years, five more years.

This podcast is produced and edited by me Jamie Benning.

Music is by Michael Hewitt Brown of MBI Music five more years.

Speaker 1Yeah, weirding wave media