Episode Transcript

[SPEAKER_00]: Today, on misunderstood with Rachel Yucatan.

[SPEAKER_01]: The inbilical cord was tied in a knot and around my neck.

[SPEAKER_01]: So had I been born naturally, I would have been dead.

[SPEAKER_01]: When I was about eight years old, my parents were told they needed to have me evaluated.

[SPEAKER_01]: So the woman said to my parents, it's very difficult to understand what's going on inside his head.

[SPEAKER_01]: A learning disability is a 20-point spread.

[SPEAKER_01]: I had a 70-point spread.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the doctor goes, oh my God, this is a lucky baby.

[SPEAKER_01]: The luckiest baby, the born lucky is the book.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's my story of growing up with autism and my dad quitting his job to adapt me to the world rather than the world to me.

[SPEAKER_00]: You've talked about moments where you're holding onto your beliefs and it carried professional consequences.

[SPEAKER_00]: Could you talk a little bit about that?

[SPEAKER_01]: I've had confrontational interviews with Democrats.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've had confrontational interviews with Republicans.

[SPEAKER_01]: That's what you want to have had to do.

[SPEAKER_01]: And we now know at that moment, Mofflin Murdoch sent an email to Jay Wallace and Suzanne Scotter that had a Fox News and said Lee Lens done.

[SPEAKER_01]: Feelin' pretty low and feelin' pretty started for myself and I was sittin' everyone night talkin' to my dad.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he looks at me and goes, feelin' pretty started for yourself, aren't you?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I said, I am, and he goes, all right, he goes, I get it, he goes, but you feel pretty started for yourself and eighth grade.

[SPEAKER_01]: And you got up every morning, you went back to school.

[SPEAKER_01]: You can do this.

[SPEAKER_00]: Welcome back to Ms.

[SPEAKER_00]: Understood, I'm your host Rachel Yucatel.

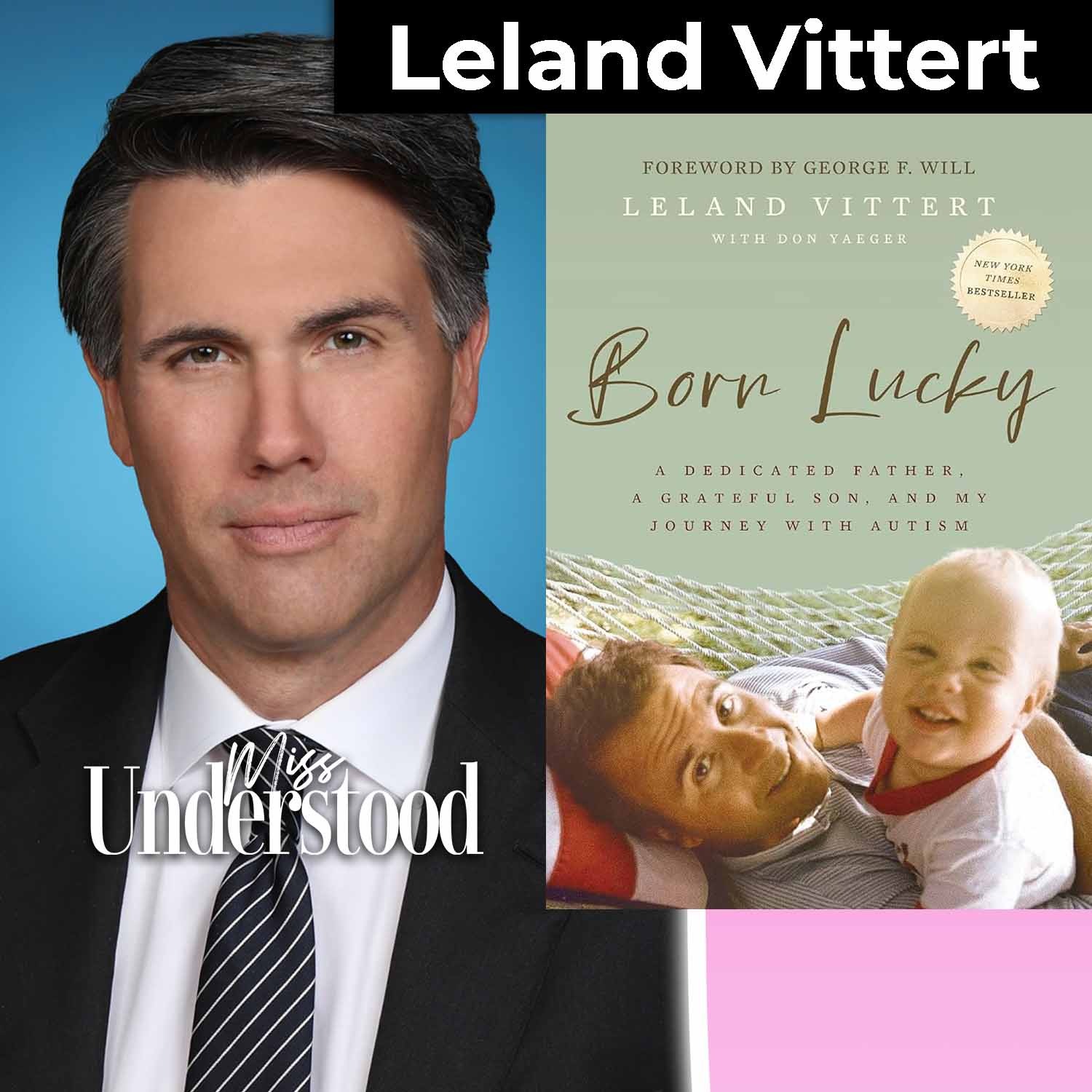

[SPEAKER_00]: You probably know Leeland Vittard from television, as a seasoned journalist, anchor, and national correspondent on News Nation now where he brings clarity to the chaos in the news cycle with sharp instincts and a steady voice.

[SPEAKER_00]: But what you don't know, what few people have known until recently, is the story that shaped the man that you see on your screen.

[SPEAKER_00]: Leeland has a new book out this year called Born Lucky, a dedicated father, a grateful son, and my journey with autism.

[SPEAKER_00]: And that title doesn't just hint a compelling read, it reveals a life few could have predicted.

[SPEAKER_00]: In Bornlucky, Leeland opens the door on a childhood marked by silence, isolation, misunderstanding, and relentless bullying.

[SPEAKER_00]: Long before anyone ever whispered the word's autism or being on the spectrum.

[SPEAKER_00]: He didn't speak until he was three, teachers didn't see a future, they saw weird.

[SPEAKER_00]: The world around him often didn't know what to make of him.

[SPEAKER_00]: But what did know him was one man, his father, a dad who quit his job who became his coach, his teacher, his guardian against a world that barely understood him, a father who lived by a set of principles that weren't in any textbook, but would eventually teach a boy how to look his challenges in the eye and thrive anyway.

[SPEAKER_00]: This is a book about what it was like living with autism.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yes, but it's also what every parent and every child who's ever felt misunderstood desperately needs to hear that there's hope that there's a path forward and your diagnosis does not define your destiny.

[SPEAKER_00]: Today you're going to hear a story of how a little boy who was written off became a man who speaks four millions and why one father's devotion still sounds like a love letter decades later.

[SPEAKER_00]: We'll thank you so much for joining me today on misunderstood how are you?

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh fantastic.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's great.

[SPEAKER_00]: So, I received your book a couple days ago and I've started reading it, I haven't been able to get through it yet, I will finish it.

[SPEAKER_00]: But I want to tell you, in reading this, you know, I don't have autism, I don't know anyone that has autism and I want to say that as a parent and as I guess a human that has felt misunderstood for most of my life, I was in tears very quickly in reading this because it resonated with me and [SPEAKER_00]: Like I felt like I totally get this person, you know, like a meeting you now, but as I was reading it, I was like I totally understand I understand those feelings, everything you were saying.

[SPEAKER_00]: And so I just want to tell you that, you know, right from the beginning because I think it's so interesting that it's a book about you and your relationship with your father and growing up different autism, but it's like a book for everyone to read because it's such a universal feeling and that comes across.

[SPEAKER_01]: really like you.

[SPEAKER_01]: The book ends pretty well, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: I won't spoil it for anybody, but I'm now happily married and have a wonderful wife and a great job, and it's proof as we like to say of what great parenting can do.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, born lucky is the book.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's my story of growing up with autism and my dad quitting his job to adapt me to the world rather than the world.

[SPEAKER_01]: To me, and I think Rachel, what you picked up on is that it goes way beyond autism, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: This is hope for every parent of a kid having a hard time.

[SPEAKER_01]: Doesn't matter why, doesn't matter if it's ADHD or anxiety or bullying or physical issue or just not understanding how to grow up.

[SPEAKER_01]: This is hope for every parent of a kid having a hard time about really what they can do and how the experts aren't always right.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, exactly.

[SPEAKER_00]: So, born lucky, it's a great name.

[SPEAKER_00]: Sounds metaphorical, but when you get into it, you quickly realize that it has something to do with your doctor and a nickname that you were given.

[SPEAKER_00]: Can you share that story?

[SPEAKER_00]: I thought it was so great.

[SPEAKER_01]: Sure.

[SPEAKER_01]: So 1982, my mother is 35.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's her first pregnancy, and that was high risk at the time.

[SPEAKER_01]: So her doctor sees on the ultrasound, before she sophisticated ultrasound, [SPEAKER_01]: And there I was upside down.

[SPEAKER_01]: So she comes out of the appointment that last appointment before she gave birth to see my dad.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad was a business guy.

[SPEAKER_01]: The time wasn't really involved in his wife being pregnant.

[SPEAKER_01]: And says to my dad, you know, I'm really concerned about this and the doctor thinks it should get a C-section.

[SPEAKER_01]: If the time having an actual birth was very much in Vogue and it was all this research, the doctors were having C-sections because it was more convenient on and on.

[SPEAKER_01]: And my mom and dad go back and forth and my mom finally decides, you know, if I'm not going to take my doctor's advice, I should find a new doctor.

[SPEAKER_01]: But if I'm going to have this doctor, I should take this advice.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I mean more advice via C section in the hospital and there's that like blue curtain separating from where I'm being born from my mom and dad and my my dad's holding my mom's hand and and everything's going fine.

[SPEAKER_01]: And then all of a sudden from the other side of the blue curtain, my parents here, oh my God.

[SPEAKER_01]: not what you want to hear.

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh my god, really not what you want to hear in an operating room.

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh my god, this is a lucky baby.

[SPEAKER_01]: And my mom's hand just like vise clenches on my dad's.

[SPEAKER_01]: And my dad sticks his head around and goes, hey, everything okay.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the doctor goes, give us a second of anything's fine.

[SPEAKER_01]: And they go, [SPEAKER_01]: like oh my god this is a lucky baby the luckiest baby.

[SPEAKER_01]: And what it happened was is that the inbilical cord was tied in a knot and around my neck.

[SPEAKER_01]: So had I been more naturally I would have been dead or had severe cervical palsy.

[SPEAKER_01]: So the next day the uh [SPEAKER_01]: Doctor who delivered me came up to the room that my mom and I were in and there was one of those little whiteboards outside the room that said like, you know, Leeland Vinter, how much I weighed when I pooped, whatever else it was, and he crossed out Leeland and he wrote, call him lucky.

[SPEAKER_01]: So from when I was a little boy, I introduced myself as lucky Vinter and I [SPEAKER_01]: actually came up with a title of the book sort of at the very beginning of just writing a few words about my dad and the reason I did is I wanted it to be so clear of how lucky I felt and in this age of victimhood and age of diagnosis and age that everybody is got a problem and needs to be met where they are and celebrated and what was me I really wanted to sort of acknowledge [SPEAKER_01]: what I believe to be true is just how lucky I am in so many ways.

[SPEAKER_00]: I love that.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's such a great story.

[SPEAKER_00]: So can you like you start the book off talking about how different you were, how different you came across to other people.

[SPEAKER_00]: And you know, if you can tell us a little bit about what you're, I don't want to call symptoms, but like what you, how you were and how others perceived you in your childhood and what that was like.

[SPEAKER_00]: Because I think there are some of the conversations about [SPEAKER_00]: autism and aspergers and all these things on the spectrum and people don't aren't sure about what symptoms are that are real that are fake, you know, all that stuff.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, no, I think the best way it was described once, and I don't remember if it's autism speaks or autism society, part of the way I grew up is my parents never told me that I was diagnosed with anything, they never wanted me to define myself as a diagnosis, they never wanted anyone else to define me by it, they never wanted me to have an excuse.

[SPEAKER_01]: But later on, I've learned in one of these groups says something along the lines of a few met one child with autism, you met one child with autism.

[SPEAKER_01]: So it's different for everybody.

[SPEAKER_01]: When I was about eight years old, my parents were told they needed to have me evaluate it, which is the worst thing in the parent can hear, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: So they take me one of those medical office buildings, little inflores, bad lighting, stale coffee, old magazines.

[SPEAKER_01]: They sit there for a couple of hours before cell phones, so they're pretty nervous.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the woman comes back and she says, boy, your boy's got a lot of problems.

[SPEAKER_01]: Big behavioral issues.

[SPEAKER_01]: I hadn't been invited to a play date or a birthday party for a long time at that point.

[SPEAKER_01]: But, you know, if somebody touched me in a classroom or in a lunch line or a movie line or a tour of wherever I was, I'd turn around in Sluggler.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I couldn't play on the playground.

[SPEAKER_01]: I really had no ability to interact with kids in my own age.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I was a fat little kid.

[SPEAKER_01]: So if I sluggged somebody, it was impactful.

[SPEAKER_01]: Uh, I had big sensory issues.

[SPEAKER_01]: Um, so if I was wearing socks, I didn't like that were roll, you know, that were on my calves or wherever I didn't like.

[SPEAKER_01]: I would melt down, same with a jacket that they would just sort of be over because I would lose it.

[SPEAKER_01]: And then what they discovered in this test was I had huge learning disabilities.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, and IQ test is two halves of, um, these tests and your scores are average together.

[SPEAKER_01]: Right.

[SPEAKER_01]: Uh, [SPEAKER_01]: So the woman said to my parents, this was the biggest spread they'd ever seen.

[SPEAKER_01]: And in her words, it's very difficult to understand what's going on inside his head, meaning my head.

[SPEAKER_01]: Now my wife would tell you it's still very difficult to understand what's going on inside my.

[SPEAKER_00]: I think all women say that about men.

[SPEAKER_00]: Don't worry about that.

[SPEAKER_01]: They may be right.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I believe it married for six months, so I'm learning.

[SPEAKER_01]: But [SPEAKER_01]: The, the woman said it's very difficult to understand what's going on inside his tent.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad goes, okay, what do we do?

[SPEAKER_01]: Any father would ask that.

[SPEAKER_01]: She goes, well, there's not much you can do.

[SPEAKER_01]: You kind of have to meet him where he is.

[SPEAKER_01]: And where I was was a disaster.

[SPEAKER_01]: But a total disaster.

[SPEAKER_01]: So that is where he decided he was going to have to try to adapt me to the world rather than the [SPEAKER_00]: Right, and not only that, I mean, you talk about in your book that you were born cross-eyed, you didn't speak until you were three.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, it's so interesting to look at you now, this handsome man who's in television and communicates as a profession and to think that you went through that.

[SPEAKER_00]: And that's what, you know, so many people do not understand about, you know, when you look at somebody today, you have no idea what they went through, whether it's that day or in their life.

[SPEAKER_00]: So it's fascinating to see that.

[SPEAKER_00]: So I want to talk about labels because you brought that up.

[SPEAKER_00]: Um, I have a, I don't know how I feel about labels because I do have somebody in my family who was bipolar or something.

[SPEAKER_00]: And when she was in her teens, she was diagnosed as that.

[SPEAKER_00]: She has meant the rest of her life acting that out.

[SPEAKER_00]: And, [SPEAKER_00]: to me, I was like, what do you mean?

[SPEAKER_00]: She just has a big personality.

[SPEAKER_00]: She's great.

[SPEAKER_00]: Stop medicating her, stop telling her that because she's just going to act that out.

[SPEAKER_00]: And that is how her life turned out.

[SPEAKER_00]: It didn't turn out great at all.

[SPEAKER_00]: What does your thought on labels?

[SPEAKER_00]: Because you weren't told until you were in college and wondering, do you think that made a difference?

[SPEAKER_00]: Do you think that you would have acted out a different way?

[SPEAKER_01]: I don't know any other way to be other than who I am, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: So people have asked me, well, what was it like growing up on the spectrum?

[SPEAKER_01]: What was it like dating on the spectrum?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I don't know how or what's like being a journalist on that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I have no idea, because I don't know what it's like to be anything different than me.

[SPEAKER_01]: What I can tell you is, is I think not allowing myself or not allowing me, I guess, my parents did, to have a excuse or a crutch.

[SPEAKER_01]: really important.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I'll give you an example.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that is that dealing with autism, the same is dealing with, for example, bipolar or anything else.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's a lifelong battle, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I've equated being autistic a little bit to being an alcoholic.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's something you have to work on every day.

[SPEAKER_01]: And there's a discipline to do it every day.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, you think about that, and a couple of months ago I was playing golf with my father-in-law, and we got teamed up, we're out west with this other older man, lovely round of golf at his club, and we finished playing, and I'm running late.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've got to be somewhere, and I'm trying to stuff my golf bag into the travel bag.

[SPEAKER_01]: And so we're out by the card barn, [SPEAKER_01]: I'm wrestling with it, and my father-in-law goes into the clubhouse to, I don't change issues or whatever, and the guy that we're playing with walks over.

[SPEAKER_01]: and says, hey, Leeland, and he's sort of looking down at me and I'm down on the ground trying to put the bags into the travel bag or the clubs in the travel bag.

[SPEAKER_01]: And what are the classic sort of symptoms or whatever you want to call characteristics of autism is you become very task-focused, just hyper-task-focused, which I did.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he kept saying, hey, Leeland, I go, aha, and I'm just putting the clubs in and wrestling with them.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I couldn't help myself.

[SPEAKER_01]: I couldn't stop.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I could hear my father in my head of eighth grade, lucky veteran or eight-year-old lucky veteran saying, okay lucky, you need to stop.

[SPEAKER_01]: You need to get up.

[SPEAKER_01]: You need to look Mr.

McGill Academy in the eye.

[SPEAKER_01]: You need to talk to him for a minute.

[SPEAKER_01]: Five minutes late is not going to change anything right now.

[SPEAKER_01]: Like you've got to sort of [SPEAKER_01]: breakout of how you are.

[SPEAKER_01]: I couldn't do it.

[SPEAKER_01]: I was so rude to this guy, eventually he just walked away because I couldn't stop and talk to him.

[SPEAKER_01]: It sounds weird, but that's what was happening.

[UNKNOWN]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: I found his phone number afterwards, and I wrote him a note just saying I would just want to apologize for being so phenomenally rude to you, I was late, didn't know what I was thinking, but just no excuse, I'm very sorry.

[SPEAKER_01]: What I didn't follow up with was, oh, by the way, that's my autism, or I have autism, or by way of explanation, or don't blame me, blame the autism.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: Because my dad never let me do that.

[SPEAKER_01]: He ever let me have extra time on tassie, never let me.

[SPEAKER_01]: have behavior modification plans.

[SPEAKER_01]: Whatever it was, the standard was the standard.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think that was a really powerful tool for me later on in life as to the agency tool.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think it was a great gift.

[SPEAKER_01]: It was much harder on him because he had to deal with all the issues that went along with his son having these issues and not getting accommodations.

[SPEAKER_01]: But not ever being able to be labeled and not ever being able to use that label as an excuse is really been powerful for me.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, it's one thing to what you're talking about.

[SPEAKER_00]: Now, use it as an excuse.

[SPEAKER_00]: But do you think it would have explained things to yourself a little bit earlier?

[SPEAKER_00]: So you could say to yourself, okay, well, I'm not, this isn't strange.

[SPEAKER_00]: This isn't me being different and weird.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's like I have something going on and I just have to figure out how to navigate it, which you eventually did with your father, you learned and you were coached.

[SPEAKER_00]: But do you think it would have helped you to understand you better?

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh, I understood I was pretty weird.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay, it makes a lot of sense.

[SPEAKER_00]: And but as you grew up, like explain to me what it was like inside your head, like where you lonely were you.

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh yeah, no, I mean, that pro look, you know, kids inherently know what's happening, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: You know what, I was in fifth grade.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've been to two or three schools.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad came over to this little, [SPEAKER_01]: grade school that I was going to went up to the PE fields because you know I was in PE and asked the PE teacher hey how's lucky doing?

[SPEAKER_01]: And the guy goes oh I think he's your better this month and my dad's a great look like that's go find him.

[SPEAKER_01]: And this guy was a big guy my dad knew him from football at a different school.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad was a great athlete.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the coach because I don't think that's a good idea.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad goes why not?

[SPEAKER_01]: Coach goes, well, kind of looking out over the playing fields says I had to put them with the girls, right, I goes, what?

[SPEAKER_01]: And the guy goes, yeah, I've put them with the girls for the past month because, you know, I had to protect them, the boys just bullied them too badly.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, you know, same school, I got pulled out of that school later, later on, I fifth grade year, but same school, [SPEAKER_01]: My sister was a kindergartener and when we were writing born lucky I asked her you know what are your first memories of me and she said oh that's easy and fifth group when you were in fifth grade I was in kindergarten You would walk down from your classroom Pick me up when we'd walk across the PE field so you go home every day because it was a path at the end of the woods and He And she said every day As we got to the woods you would start crying [SPEAKER_01]: Every day and I your sister would hold your hand.

[SPEAKER_01]: So yeah, I mean, I knew what was going on.

[SPEAKER_01]: I knew in eighth grade when there was a teacher who didn't think that I was going to become Picasso is an art teacher and they're in our class.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I guess he didn't like a drawing I made or whatever.

[SPEAKER_01]: I don't know.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he said for the whole class like 28th graders, hey, Vincent, if my dog was as ugly as you, I would shave its ass and make it walk backwards.

[SPEAKER_01]: and the whole class laughter, and then also if you understand if the teachers are doing that, what the kids are doing.

[SPEAKER_01]: So yeah, I knew I knew precisely what was happening and there was a there was an emotional cruelty and isolation that exists.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the boy lucky story is my dad taking the hard road with me, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: It's he chose to help me embrace the adversity and held my hand through it.

[SPEAKER_01]: So every night, [SPEAKER_01]: You know, he's been a couple of hours putting me back together and taking that social and emotional toll on him off of me and I would either yell or I would cry or I would you know talk about how unfair things were and he'd listen late into the night and I now know because my mom told me when we interviewed her for the book.

[SPEAKER_01]: That dad, often after he would leave my room, I'd start homework or go to sleep, whatever.

[SPEAKER_01]: He would come downstairs in our living room by himself and sit there and cry himself late at night.

[SPEAKER_01]: And one to a clock in the morning, my mom would find them.

[SPEAKER_01]: So that born lucky story is really apparent choosing to embrace adversity with their child and help their child through the adversity rather than take the adversity away.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, what's interesting to you about your book is that it's not just you writing the book.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's really, you talk so much about your father and what he did to get you through it.

[SPEAKER_00]: And what, I mean, it was just fascinating, the parts that I've read so far.

[SPEAKER_00]: And I will say I skipped to the end to read his was a called afterward is the thing he writes at the end.

[SPEAKER_00]: His afterward, yeah.

[SPEAKER_00]: Which?

[SPEAKER_00]: That was what had me in tears too, because it was so, first of all, I don't know if he's a writer, but it was so well written.

[SPEAKER_00]: And in a short, you know, whatever it was words, 500 words, whatever it was, he captured the most beautiful tribute.

[SPEAKER_00]: Not only to you, but to him, like to what he went through, but it sounded like he was a man.

[SPEAKER_00]: He wasn't this like pussy guy that was like, I had to give him my job and I had this weird kid.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, he was, I close the book and I started crying.

[SPEAKER_00]: I was like, wow, what a guy this was.

[SPEAKER_00]: Is.

[SPEAKER_00]: And so anyways, let's talk about your dad.

[SPEAKER_00]: So as we go through the book, we really see that your father has become this coach to you and coaches you through.

[SPEAKER_00]: your difficulties.

[SPEAKER_00]: Can you explain some of like what he was teaching you?

[SPEAKER_00]: Because I think a lot of parents these days would like go to a doctor and be like, what medication do I do, you know?

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, well that that is true and a couple of things I'll let your listeners do not know something that's not in the book.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think every one who reads born lucky will agree that the afterword is the best part, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: I the unviewable task, an unviewable task of filling [SPEAKER_01]: It was just tough writing, but dad, [SPEAKER_01]: Dad, as you read in the afterward, hates being called a hero.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he says, I just did what any parent would do.

[SPEAKER_01]: I just tried to help my boy.

[SPEAKER_01]: So the way that all came about is he really didn't want to do this book.

[SPEAKER_01]: He thought it could help people, which it has.

[SPEAKER_01]: And we've gotten hundreds of letters.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's just been phenomenal.

[SPEAKER_01]: But as we started writing it, every time we would begin a story or talk about something my dad would go, gee, I...

[SPEAKER_01]: You know, do we really want to say that?

[SPEAKER_01]: Do we really want to do this on and on and on?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I'd say, you know, finally, as a dad, like, look, we can't just adjudicate every story.

[SPEAKER_01]: Either we tell the story or we don't.

[SPEAKER_01]: So what we're going to do is we're going to write it, you're going to be as candid as you can.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'll give you the manuscript.

[SPEAKER_01]: And if you don't like it, I will not turn it into hypercolons.

[SPEAKER_01]: fine.

[SPEAKER_01]: So Tuesday rolls around, um, uh, of, of, of, of, of, of when we're the manuscript is due, and I have deadline week.

[SPEAKER_01]: And, [SPEAKER_01]: It's due on a Friday.

[SPEAKER_01]: So on Tuesday, I hand him the manuscript, and I say, take a look.

[SPEAKER_01]: He reads it on Thursday calls me, he goes, I don't know if I can do this.

[SPEAKER_01]: This is just too hard, it's too raw, it's too emotional, it's now exposing all these things we never told anybody about, you know, he never told his friends, obviously no teachers, counselors, therapists, nothing.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I said, all right, Dad, I said, how about this?

[SPEAKER_01]: If rather than told you there was no hope, the woman who diagnosed me, had instead handed you a copy of born lucky and said, look, this isn't a prescription, it's not a cure, but this is just what one father did.

[SPEAKER_01]: This is a love story of a father and a son.

[SPEAKER_01]: What would you have done?

[SPEAKER_01]: He said, I would have read it every week because it would have given people hope.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yes.

[SPEAKER_01]: Well, I think that's your answer.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he said, [SPEAKER_01]: Okay, but I don't like that it makes me a hero and you can't call me a hero and it makes me seem like I'm a hero I said, well, why don't you say that?

[SPEAKER_01]: He goes, what do you mean?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, why don't you write the afterward?

[SPEAKER_01]: Just write, just write how you feel right now.

[SPEAKER_01]: Just write what you're telling me and he goes, well, I only do whatever other father would do.

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, okay, write that and he said, when do I have to give it to you?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, well, it's Thursday at 10 p.m.

And this is due tomorrow at 9 a.m.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I'd say right now and he goes, [SPEAKER_01]: Okay.

[SPEAKER_01]: And about an hour later, he called me back and he dictated to me.

[SPEAKER_01]: He had written it down longhand.

[SPEAKER_01]: He dictated to me what is the afterward of the book?

[SPEAKER_01]: As you pointed out, it's the best part.

[SPEAKER_01]: And he wrote it in about an hour.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think in the edit, we changed in that whole five or six hundred words, one comma or one word, something like that.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that's just how what he felt.

[SPEAKER_00]: That was what was your reaction when he read it to you?

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh, I started [SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, I saw I just I lost it till you know he felt that way or had you ever communicated that to you [SPEAKER_01]: It's something interesting, you know, my dad lost his dad at 16, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: And in Bornlucky, we have the letter that was written to my dad that my dad got on the the night of his father's death, it was a surprise, his older brother, about 10-year-old, the brother came back to the house, more my dad was living with his parents, and my dad was shaving, getting ready for a date on a Saturday, and his brother came in the room and said, [SPEAKER_01]: and drove down to the family construction company office open the safe in my grandfather's office and pulled out this letter that had been written.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the letter talked about how a man is defined by his character, not by his accolades or his achievements or his net worth or anything else, but by defined by who he is a man is his character.

[SPEAKER_01]: And my dad's always tried to live up to that and always wondered if, you know, he made his dad proud, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: It was always this unattainable benchmark that my grant, he felt my grandfather and set.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've never had to deal with that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've always known my dad was proud of me because he's always told me that.

[SPEAKER_01]: He's always been my best friend and the most loving and loyal and kind and in generous father and friend anyone could have.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, [SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, did I know we felt that way about me?

[SPEAKER_01]: Sure.

[SPEAKER_01]: Do I still cry when, you know, I read inborn lucky?

[SPEAKER_01]: I did the narration for the audiobook, and I read the letter that my father read his grandfather wrote.

[SPEAKER_01]: I cried.

[SPEAKER_01]: I cried when I read the letter that my dad gave me before I went overseas to be a foreign correspondent.

[SPEAKER_01]: You know, trying to try to narrate that audio without, without crying was, was hard.

[SPEAKER_01]: But I think that's what the readers, I don't want to say demand, but I think the reason this book is resonated the way it has.

[SPEAKER_01]: Um, not, not measured by sales, but measured by the number of letters I've gotten from families who now say we're not alone, we feel hope we feel we feel like we have a chance on and on is because it's been so emotionally raw.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, yeah, and I love that part about your grandfather and the letter and I read that and it was so emotional to read it and it's the through lines throughout your book.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, that's that's how you grew up.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's very obvious and it was obvious that your father and still that in you too.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, you've talked about moments where you're holding onto your beliefs and it carried professional consequences.

[SPEAKER_00]: I know that that happened at the end of your fox curve.

[SPEAKER_00]: Could you talk a little bit about that?

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: No, you know, TV TV news is an interesting dynamic.

[SPEAKER_01]: The one thing my dad didn't tell me when I was in eighth grade and seventh grade ninth grade, whatever it was, having just the horrible time and the emotional cruelty was that this is going to be great training for a Washington newsroom.

[SPEAKER_01]: right, because middle school is by far the best training for Washington, New Zealand.

[SPEAKER_01]: But what happened was, I was at Fox, and it was clear that [SPEAKER_01]: I had, I had sort of been, I don't want to say push to side, but it was clear that I was no longer the flavor of the month in terms of doing real journalism.

[SPEAKER_01]: The management had changed, the person who had hired me in champion me had left, had been fired very wrongly.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I was still anchoring them on the weekends.

[SPEAKER_01]: And this was right after the 2020 election, Joe Biden had won Trump, had said it was stolen.

[SPEAKER_01]: And about two or three weeks after the election, I was anchoring on a weekend during one of what they called the stop, the steel rally.

[SPEAKER_01]: So it was big groups of people coming into Washington to protest.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I had one of Trump's spokespeople on.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I just started asking basic journalistic questions about, [SPEAKER_01]: where is the evidence of this being stolen?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think it's always sort of just insulted my sense of decency when people sit there and lie to your face, just because of what my dad taught me.

[SPEAKER_01]: And so I kept pushing back.

[SPEAKER_01]: And it got pretty confrontational, as I've had confrontational interviews with Democrats.

[SPEAKER_01]: I had confrontational interviews with Republicans, just sort of what I think a journalist's job is.

[SPEAKER_01]: And we now know at that moment, Lachlan Murdoch sent an email to J.

Wallace and Suzanne Scott, where the head of Fox News and said, Lee Lynn's done, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: So I didn't know that at the time.

[SPEAKER_01]: I was told the time you'll never anchor again.

[SPEAKER_01]: And so you think about what happened in that span, so that was the middle of November.

[SPEAKER_01]: Middle of December, I was told, I'll never anchor again.

[SPEAKER_01]: middle of December, I ended a long-term relationship that I'd been in with a pandemic, young woman for about eight years, and we were living together, weren't more engaged or married, but living together, and ended that relationship.

[SPEAKER_01]: And...

[SPEAKER_01]: So I had nowhere to live, no job, no significant other.

[SPEAKER_01]: And then early in January, I got COVID, no most died of COVID.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I was in the hospital for about a week and I end up now in my parents' house and Florida literally just with a backpack on my back of my stuff.

[SPEAKER_01]: And Fox was still paining me, but I had no job.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I, [SPEAKER_01]: feeling pretty low and feeling pretty sorry for myself and I was sitting there one night talking to my dad was almost like I was back in eighth grade and he looks at me goes feel pretty sorry for yourself aren't you and I said uh-huh I am and he goes alright he goes I get it he goes but you feel pretty sorry for yourself and eighth grade and you got up every morning you went back to school [SPEAKER_01]: and you can do this, you know, and it occurred to me that had I not had that really serene experience that I not walked through hell before.

[SPEAKER_01]: I wouldn't know the way to get out of hell is to keep walking.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that is a really, really powerful gift that parents can give kids and so many don't.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, wait, so what was that path out of there?

[SPEAKER_00]: Cause did you think your TV career was over?

[SPEAKER_00]: How did you get that next move?

[SPEAKER_01]: It's really interesting.

[SPEAKER_01]: Um, as chance would have it, um, right about the time that the, um, Fox situation was happening.

[SPEAKER_01]: I started talking to News Nation, News Nation wanted to launch.

[SPEAKER_01]: We wanted, they wanted to see the world right, verse wrong, not left first right, Sean Compton, who is the president of the network, had the idea of, of creating network with Midwestern values.

[SPEAKER_01]: Um, he's from the Midwest, I'm from the Midwest, and we started talking and then kind of one thing led to another and by May, I moved to Chicago to help effectively relaunch in his nation, uh, which was great.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's been a great experience.

[SPEAKER_01]: And you know, you think about what happened at Fox, which, [SPEAKER_01]: anyone would say was unfair, was wrong, was all these things, none of these great things would have happened.

[SPEAKER_01]: I would have never met my now wife because I met her on a blind date in Chicago the second day of work and I would have never married the love of my life and I never would have had this great new adventure.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, you know, good things happen out of really terrible adversity.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, I agree with that.

[SPEAKER_00]: I'm curious because communication is what you do for living and you're so good at it.

[SPEAKER_00]: I think people listening and hearing the story are like, yeah, but how did he do that?

[SPEAKER_00]: How do you go from someone who has autism?

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, isn't part of autism like the connection?

[SPEAKER_00]: It's hard to make connections with people like, [SPEAKER_00]: You have to look at people.

[SPEAKER_00]: You have even though we're on Zoom, like we have to look each other in the eye kind of and like be here and you're just as present as anyone else.

[SPEAKER_00]: So how did you get there and when did you learn that it was like, oh, I'm good at this and and I'm not trying hard.

[SPEAKER_00]: It just comes naturally or does it never come naturally.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's it's in every day battle.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's a minute by minute battle, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: It's a learned scale and I'll I'll back up this and this also is in the book.

[SPEAKER_01]: So for your listeners and viewers a little a little behind the scenes of born and lucky the reason this whole thing happened was exactly what you're talking about Rachel and you're so perceptive to pick up on it.

[SPEAKER_01]: I had gotten the job at News Nation, and I was starting to be a prime time anchor versus being a anchor, you know, weekend anchor and reporter.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I was working with this talent coach.

[SPEAKER_01]: And she kept talking to me about that emotional connection with people and how to match the emotional connection of what they call the two box.

[SPEAKER_01]: So if your producer puts it up, where we're both next to each other, they call that the two box and how to match the emotional energy of the person you're interviewing.

[SPEAKER_01]: So, she keeps talking to me about it, you know, session after session after session.

[SPEAKER_01]: And she finally sort of was like, do you understand what I'm saying?

[SPEAKER_01]: Right.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, I get it.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm working on it.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm working on it.

[SPEAKER_01]: She goes, is it hard for you?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, it's really hard for me.

[SPEAKER_01]: She said, well, why?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I said, well, I said, I'm autistic.

[SPEAKER_01]: Silence, for like 30 seconds.

[SPEAKER_01]: And she goes, what did she say?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I said, well, I'm autistic.

[SPEAKER_01]: She goes, you have autism, I said, huh?

[SPEAKER_01]: She was, I didn't know that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, well, nobody knows that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, I'm gonna pull the anybody.

[SPEAKER_01]: She was, you never told your bosses?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, no.

[SPEAKER_01]: Well, I mean, she sort of blew her mind.

[SPEAKER_01]: Right, right.

[SPEAKER_01]: And she goes, what is this?

[SPEAKER_01]: What is this?

[SPEAKER_01]: What are you talking about?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I said, well, this is sort of the boring lucky story, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm diagnosed when I was eight years old.

[SPEAKER_01]: My parents told nobody.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad tried to adapt me to the world on and on and on.

[SPEAKER_01]: And she goes, I don't believe this.

[SPEAKER_01]: Have you ever written anything about it?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, well, actually, I wrote about 700 words.

[SPEAKER_01]: Um, then I planned at some point to publish is like an op-ed like a father's day op-ed to thank my dad.

[SPEAKER_01]: He's actually titled born lucky.

[SPEAKER_01]: I literally wrote it one night after a few too many glasses of wine, um, and never looked at it again.

[SPEAKER_01]: If she was, could I read it?

[SPEAKER_01]: I said sure.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I sent it to her and she then sent it around to people unbeknownst to me and, uh, somebody.

[SPEAKER_01]: read it instead I really wanted to turn this into a book, but you very long answer to the sort of the understanding of the human equation that I have is a learned skill taught by my dad.

[SPEAKER_01]: So for example, when I was a little boy, he would take me to lunch with his friends, because I couldn't go to lunch with kids and I couldn't do play dates or anything like that.

[SPEAKER_01]: But if he was with me and he was my best friend, he would take me to a lunch or whatever.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the deal was, I could come and have these great interactions, but when he tapped his watch, I had to stop talking.

[SPEAKER_01]: So that was my message to A stop talking and be bookmarked the situation.

[SPEAKER_01]: So we'd be out to lunch with somebody and as soon as we'd sit down, I'd start hammering away about whatever the guy's business was or a profession or whatever it was.

[SPEAKER_01]: I was a kid in a thousand questions.

[SPEAKER_01]: My dad would tap his watch, I'd stop talking.

[SPEAKER_01]: And then later we would post game, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: So when Mr.

McGillacuddy was talking about his wife in her gardening, you interrupted Mr.

McGillacuddy [SPEAKER_01]: how you're trying to do 200 pushups a night to earn a trip to Disney World, which is something my dad would have me do.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I go right to that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I thought that was really interesting.

[SPEAKER_01]: He'd go, okay, what could we ask Mr.

McGill a cutty about his wife that would be interesting?

[SPEAKER_01]: And it was an role playing of that really intimate understanding of the human equation that that comes so naturally just so many, that for me is a learned skill.

[SPEAKER_00]: Right.

[SPEAKER_00]: So, it's interesting because I think back then, when you were growing up, it sounds like, and it's clear.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, you grew up and were successful despite whatever you were diagnosed with or labeled with, and it didn't really affect you.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, it affected you, but it wasn't an issue.

[SPEAKER_00]: You are where you are in very successful.

[SPEAKER_00]: Now a days and correct me if I'm wrong.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's because again, I'm not involved in the asked burgers, autism, whatever the labels are world, but it seems like we have the mental health days and everybody claims to be autistic when they don't want to do things.

[SPEAKER_00]: And or somebody acts bizarre or weird or different, you just say that's what they have.

[SPEAKER_00]: And the environment has to meet them where they are.

[SPEAKER_00]: Whereas back then, it seemed like, or at least for you, you rose despite it.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know what I mean?

[SPEAKER_00]: And you met the environment, the environment didn't have to meet you.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, and even back then there was offers for lots of accommodation sort of the late 80s into the 90s when I went to high school at the late 90s there was a lot of accommodations offered right so that that that that was beginning to be invoked.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think the fact that there were not meant that I had to learn to swim on my own, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: And as I've said, that was a lot harder on my parents because there would be a lot easier to say, hey, look, he's just him.

[SPEAKER_01]: He's just kind of kind of like, you know, let him be who he is, they didn't do that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think we now are learning the damage that has been done to generations of kids by embracing that.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I don't say that.

[SPEAKER_01]: likely, but you know, the Wall Street Journal out this month with the last month now for in December, huge article about the massive over-prescription of ADHD medication to kids at three years old and how that's changing.

[SPEAKER_01]: Breaking development and it's focusing it's forcing them to become dependent on other medications and then you've got kids in their early 20s who were on five or six different anti-psychotics.

[SPEAKER_02]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: The Columbia University teachers college out with this big study that we have created a whole new generation of kids who are anxious because they have been given accommodations for anxiety and they said the effectively the worst thing you can do is give accommodations for kids who are who have anxiety because it will just create more anxiety about whatever the thing is and you can't accommodate anxiety the rest of your life.

[SPEAKER_01]: Then there is the Atlantic, which is about as sort of classically sort of liberal and accommodating as you get with an article out called a combination nation.

[SPEAKER_01]: The 40% of the kids at Stanford University now claim some kind of disability and get a special accommodation.

[SPEAKER_01]: We had one of the professors on who was a [SPEAKER_01]: subject and highlighted in the article and he said, because if we are doing a huge disservice to the kids, but we're also a huge disservice to the country because suddenly I were creating this credentialed class of people who can't do the work.

[SPEAKER_01]: Right.

[SPEAKER_01]: Because when they get to whatever business they're in, the business, all of a sudden, is learning, well, yeah, this person got an A in physics, but only because it was graded on a curve and only because they got four times as much time as everybody else did on the test and only because they were allowed.

[SPEAKER_01]: to bring in all sorts of study material because they have a doctor's note that said they're not good at memorizing things.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, right, but also it seems like a world of excuses, too.

[SPEAKER_00]: I mean, listen, I grew up in a time where, you know, work ethic mattered and you had to go to work and you had to be there at on time and you couldn't make excuses or somebody would replace you.

[SPEAKER_00]: And nowadays, it's like, people go and they take off two weeks because they have this problem and not problem and they haven't been diagnosed, it's like anything.

[SPEAKER_00]: And that was my next question.

[SPEAKER_00]: Do you think that this self diagnosis is a thing or this is just an excuse?

[SPEAKER_01]: You know, I really am not an expert on this stuff.

[SPEAKER_01]: I, a lot of people have asked me to say, you know, what's your advice or what's this?

[SPEAKER_01]: What's that?

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm just a kid, I guess I'm 43 years old now, I'm not really a kid, but I just wrote a book about what it was like that growing up and a love letter to my dad.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I'm not wise enough for smart enough to, you know, oh, pine on what other people do.

[SPEAKER_01]: I can say that going to therapy on national television or podcasts is not really fun, you know, bearing your darkest secrets in the worst part of your life is really tough at times.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: You understand that.

[SPEAKER_01]: But if it can help other people, you know, if it can give other kids who are going through what I went through, whether it's because of autism or ADHD or just bullying and [SPEAKER_01]: the difficulties of growing up in social media, if it can give them some hope, and give families some hope, and let families know they're not alone, then it's worth it.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, then I want to talk to you about that.

[SPEAKER_00]: Watching your child struggle can be the most difficult thing and very confusing for a parent.

[SPEAKER_00]: I don't talk about this much, but even just because it was recent, but even just a few weeks ago, I have a 13-year-old daughter and she went from being like one of the most popular girls in eighth grade class to being bullied completely where no one in her class would speak to her.

[SPEAKER_00]: Without getting into all sorts of details, my question for you is, [SPEAKER_00]: as someone who was the child in the situation, but now has a bird's eye view because you've spent so much time with your father.

[SPEAKER_00]: I want to know from a kids perspective, what that pain feels like to go through the isolation and the emotions and be torn apart at school, and then come home and have a parent who just doesn't know what to do, and can offer so much like for me, I will, I got involved.

[SPEAKER_00]: I wanted to break an eighth grade or snack.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, I was in tears.

[SPEAKER_00]: I couldn't sleep.

[SPEAKER_00]: Just talking about it right now makes me cry because it's over, but I don't really know if it's over.

[SPEAKER_00]: And just watching the pain that your child goes through.

[SPEAKER_00]: Like, how does a parent deal with it?

[SPEAKER_00]: But what is that pain like for the kid?

[SPEAKER_00]: Because I don't understand because she won't tell me.

[SPEAKER_01]: Well, wow.

[SPEAKER_01]: I really feel for your daughter and I feel for you.

[SPEAKER_01]: If you read further into Bornlucky, you'll see there's a story that is almost identical to that.

[SPEAKER_01]: When I was in junior year of high school that I sort of started to figure out how to get along with people and then exactly the same thing happened overnight.

[SPEAKER_01]: No one would talk to me.

[SPEAKER_01]: The stories in Bornlucky, I won't bore you now.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'll answer what you asked.

[SPEAKER_01]: It's so crushing, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: And I was pretty used to it, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: Because by 5, 6, 7, 8, 9th grade, 10, like I had gotten used to that kind of isolation and bullying and difficulty, I really point you to what my dad had to say, and that afterward about telling your kids that [SPEAKER_01]: Um, it's going to be okay, um, middle school is not real life and the things that make you bullied and misunderstood and isolated and made fun of, um, when you're young, we'll, we'll make you successful later in life.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I'm proof of that.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm proof that if you fight through it and you don't change and you don't become one of them and you don't play their game, [SPEAKER_01]: that there is real rewards to be had.

[SPEAKER_01]: So I think that message is really important.

[SPEAKER_01]: And the thing that my dad did that was so remarkable and I think that was so much harder was, you know, he just spent hours with me listening.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that in a way was allowing me to unburden myself.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm starting to cry thinking about it and thinking about what you and your daughter are going through.

[SPEAKER_01]: So it's remarkable since I wrote this book.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've been asked to speak at different events and it's been lovely and I am at this one event now I'm doing it every event and I said, hey, I just want to understand how many of you have our parents, everybody's hand goes up fine.

[SPEAKER_01]: I said, all right, I said, if your child is.

[SPEAKER_01]: President of their class.

[SPEAKER_01]: capped into the football team or the field hockey team or volleyball team, 4.0 student has so many friends they need a Google calendar to keep everything straight and oh by the way I've never had any behavioral issues, never had any physical issues, things are just fabulous.

[SPEAKER_01]: Put your hand up.

[SPEAKER_01]: And normally in a room about 250 or 300 people, there's one person who puts their hand up and it's always a guy and I look at him and I say congratulations you have a great wife.

[SPEAKER_01]: the point being, I think you really don't understand how many families are really struggling and how many parents are going through this, how many kids are going through this.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that to me, I think, gives parents a lot of power.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think gives kids a lot of power to understand that this does get better.

[SPEAKER_01]: The part that I think is so hard now that even my dad noted, [SPEAKER_01]: who would have known how to do it, is the bullying comes home with social media, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: Oh, yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: And what I don't understand, and it's mind blowing to me.

[SPEAKER_01]: My parents don't let their kids drink, they don't let their kids use cigarettes, they say no marijuana, like all these things.

[SPEAKER_01]: But hey, here's your smartphone, and by all means, have Snapchat, it blows my mind.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, an interesting thing with that, though, is that you take Snapchat away and all the other stuff.

[SPEAKER_00]: And then they feel even more isolated, because all their friends are doing it, and they don't have it, and so now they're not part of that group.

[SPEAKER_00]: So even when I was like, okay, we're done, we're taking that all the way, so you don't see all this stuff, that almost was worse.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, because she felt like, well, I'm the only one that's now not involved at all.

[SPEAKER_00]: I have to come home and sit here and have a conversation with you.

[SPEAKER_00]: You know, but I love what your dad said because that is what I say to her, listen, high school is not going to last forever.

[SPEAKER_00]: And by the way, what a great lesson earnings Wyatt.

[SPEAKER_00]: What a great lesson Wyatt, because you now know what it's like to go through this.

[SPEAKER_00]: And sometimes it takes forever to learn how to get out of a hole.

[SPEAKER_00]: I can tell you, this has happened to me in eighth grade.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's happened to me half of my life where a lot of people didn't like me for different reasons.

[SPEAKER_00]: And I had to figure out how to be at rock bottom and climb out of that hole.

[SPEAKER_00]: And the value in that is knowing yourself, relying on yourself.

[SPEAKER_00]: You can do it.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, and know your friends are, but you can't rely on them for your happiness.

[SPEAKER_01]: Like, you know, in that knowledge because we will all end up, you know, down and whole to get down and whole again.

[SPEAKER_01]: The earlier you figure out, I can get out of this, even though it's hard, the better it is.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think the other thing for Wyatt to understand, and I've said this a lot, I've never liked anybody who liked high school.

[SPEAKER_01]: The values of high school are so screwed up.

[SPEAKER_01]: Maybe it's a little different for women than it is for guys.

[SPEAKER_01]: But the values are so screwed up.

[SPEAKER_01]: Did if you like high school, there's something wrong with you.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah, I get that.

[SPEAKER_01]: Now, I would say that that's also true about Washington.

[SPEAKER_01]: If you like Washington, the values are equally screwed up.

[SPEAKER_01]: I don't like you if you like Washington, but there's something to be said there.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's funny.

[SPEAKER_00]: Is there a piece of advice though that you would give to parents on how to react to the kid?

[SPEAKER_00]: Like you going through the bullying and all that stuff is it better for us to just sit and listen?

[SPEAKER_00]: Is it better for us to handle it?

[SPEAKER_00]: Take it to the school, figure it out for you or you just want us to be there.

[SPEAKER_01]: I wish I was good enough to give advice.

[SPEAKER_01]: I think the best advice is from my dad in the afterward that you read.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think probably given what was going on with why it had special meaning to you.

[SPEAKER_01]: to take what you can from just from the story.

[SPEAKER_01]: I've written a parenting book by a kid, and so I feel weird giving parenting advice or out of my depth, because I'm not a parent.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm a dog parent, but not a parent.

[SPEAKER_00]: Right, right.

[SPEAKER_00]: OK, speaking of which, you just got married this summer to a beautiful Rachel.

[SPEAKER_00]: And is it OK if I ask you, or kids going to be in your future?

[SPEAKER_01]: Well, you got to read the end of the book.

[SPEAKER_00]: Oh, okay.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, I'm not there yet.

[SPEAKER_01]: But I want you to get to read the end of the, I'll, that, that's it.

[SPEAKER_01]: I'm not going to give the ending of board and lock you away.

[SPEAKER_00]: Okay.

[SPEAKER_00]: Fine.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, all right.

[SPEAKER_00]: I will skip to that as soon as I get off here with you.

[SPEAKER_00]: I hope you do have kids that would be amazing.

[SPEAKER_00]: And like, are there, what are the, what are the lessons that you would take from your father?

[SPEAKER_00]: Or the things maybe that you know that you won't do going forward with your own kids if you plan on having them.

[SPEAKER_01]: You know, now I'm gonna, now you've asked a question that I have to answer and sort of give this away, right?

[SPEAKER_01]: For a long time, I told every woman that I ever dated, I didn't wanna have kids because I didn't think I could live up to what my dad was or is as a father.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that was always really hard because of how remarkable he was.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I think also because I understood, I understand even more so now having worked on the book and interviewed him, the enormous amount of work that he put in in the thousands of hours and the emotional toll and what he gave up and giving up his career and giving up really his life because for many years, [SPEAKER_01]: He was full time.

[SPEAKER_01]: It was more than full time.

[SPEAKER_01]: It was every night, every weekend.

[SPEAKER_01]: He was my only friend.

[SPEAKER_01]: He was just, he was there for me.

[SPEAKER_01]: As he said, I knew your only hope was for me to be there for you.

[SPEAKER_01]: So that is really front and center for me.

[SPEAKER_01]: That said, I just feel so privileged to have had [SPEAKER_00]: Well, it's funny because when I read the last part, the after, after word, after math, what I was called, I thought to myself, wow, isn't this interesting because people go into parenting, most many people, me, I'm speaking of me.

[SPEAKER_00]: Went into parenting, saying, I know exactly what I will do because I don't want to be like my mother, or I don't want to do what my father did to me.

[SPEAKER_00]: And so, when I read that, I thought, wow, this is interesting, [SPEAKER_00]: Leeland would never say that.

[SPEAKER_00]: Leeland, Leeland would say, I now have an example of who to be when I have.

[SPEAKER_00]: So that was what went.

[SPEAKER_01]: I mean, look, it's interesting.

[SPEAKER_01]: My wife, you know, [SPEAKER_01]: She was 35, I think when we got married 30, I can't remember when we met.

[SPEAKER_01]: Maybe she was 32 when we met, 35 when she got married.

[SPEAKER_01]: And I was 42 when I got married.

[SPEAKER_01]: Neither has been married, neither has been engaged.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that, [SPEAKER_01]: was because we both wanted to wait until we found a relationship like our parents had.

[SPEAKER_01]: Her parents have been married 43, mine have been married 53.

[SPEAKER_01]: They're still both each other's best friends.

[SPEAKER_01]: Now they're best friends with each other, but that's a different story.

[SPEAKER_01]: And that has been so important.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: That that we both have that really common understanding of what a marriage can be and what great parenting can be.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: Which is just phenomenal.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, I wish you the best of luck with that and that cannot wait to hear if and when you have children.

[SPEAKER_00]: My last question because I have to ask because it's the theme of the show.

[SPEAKER_00]: What do you think is the most misunderstood thing about?

[SPEAKER_01]: I think what I've learned when people have read the book or interview me about the book is there's this kind of idea that this is somehow a panacea or a cure or something like that.

[SPEAKER_01]: This is [SPEAKER_01]: just to father some love story and it's in every day struggle and I think that really is what I think has been what I didn't understand and what I do now having written the book and then gotten the feedback, the hundreds of letters and everything from all sorts of [SPEAKER_01]: different situations is just how many people feel so alone and feel so hopeless and how many parents just like you I mean you know who who would think that you with a beautiful daughter and honor would be struggling with this and struggling in this way and that's what I really learned is just how hard it is and how privileged I have been and honored I am to be able to give people a little bit of hope.

[SPEAKER_00]: Well, I absolutely wish you the best of luck.

[SPEAKER_00]: I want everyone to read Born Lucky, tell people where they can find the book and where they can watch you, or you nightly on.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, nightly on news nation, every night, at 9 p.m.

Eastern on News Nation.

[SPEAKER_01]: And then the books anywhere, you know, books Amazon, anywhere you wanna be, anywhere you get a book, so.

[SPEAKER_00]: What do you cover on News Nation?

[SPEAKER_00]: Is it everything or you, [SPEAKER_01]: Yeah, I mean, I mostly do politics and culture on it.

[SPEAKER_01]: So it's just a nightly cable news show.

[SPEAKER_01]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_00]: So amazing.

[SPEAKER_00]: OK, love it.

[SPEAKER_00]: Wish you the best of luck.

[SPEAKER_00]: Thank you.

[SPEAKER_00]: It's been an honor to have met you.

[SPEAKER_00]: And to hear your story, can't we to finish the book?

[SPEAKER_00]: And I wish you the best of luck.

[SPEAKER_01]: and we're what now two weeks from the wedding.

[SPEAKER_01]: Congratulations.

[SPEAKER_00]: Two weeks from yesterday.

[SPEAKER_00]: Yeah.

[SPEAKER_01]: Wow.

[SPEAKER_01]: What a what what what what an awesome time and all the best.

[SPEAKER_01]: Thank you.

[SPEAKER_01]: Thank you.

[SPEAKER_00]: Thank you so much for listening to Ms.

[SPEAKER_00]: Understood.

[SPEAKER_00]: I'm your host, Rachel, you could tell.

[SPEAKER_00]: Please be sure to subscribe to the show and give us a five-star rating and review.

[SPEAKER_00]: You can support the show by joining our Patreon at patreon.com slash Ms.

[SPEAKER_00]: Understood with Rachel, you could tell.

[SPEAKER_00]: Do you have ideas for the show or want to reach out email us at info, Ms.

[SPEAKER_00]: Understood podcast at gmail.com.

[SPEAKER_00]: That's spelled m-is-s-s-understood.

[SPEAKER_00]: Thank you so much, and I'll see you next time.