Episode Transcript

Some stories were never meant to be told, Others were buried on purpose.

This podcast digs them all up.

Disturbing History peels back the layers of the past to uncover the strange, the sinister, and the stories that were never supposed to survive.

From shadowy presidential secrets to government experiments that sound more like fiction than fact.

This is history they hoped you'd forget.

I'm Brian, Investigator, author and your guide through the dark corners of our collective memory.

Each week, I'll narrate some of the most chilling and little known tales from history that will make you question everything you thought you knew.

And here's the twist.

Sometimes the history is disturbing to us, and sometimes we have to disturb history itself just to get to the truth.

If you like your facts with the side of fear, if you're not afraid to pull at threads others leave alone, you're in the right place.

History isn't just written by the victory.

Sometimes it's rewritten by the disturbed.

The Disturbing History Podcast exists because some truths demand to be spoken aloud, no matter how uncomfortable they make us feel.

We explore the dark corners of our collective past, the chapters that textbooks gloss over, the atrocities that governments would rather we forget.

We believe that confronting these disturbing histories is not just educational, but essential, because a society that refuses to examine its sins is doomed to repeat them.

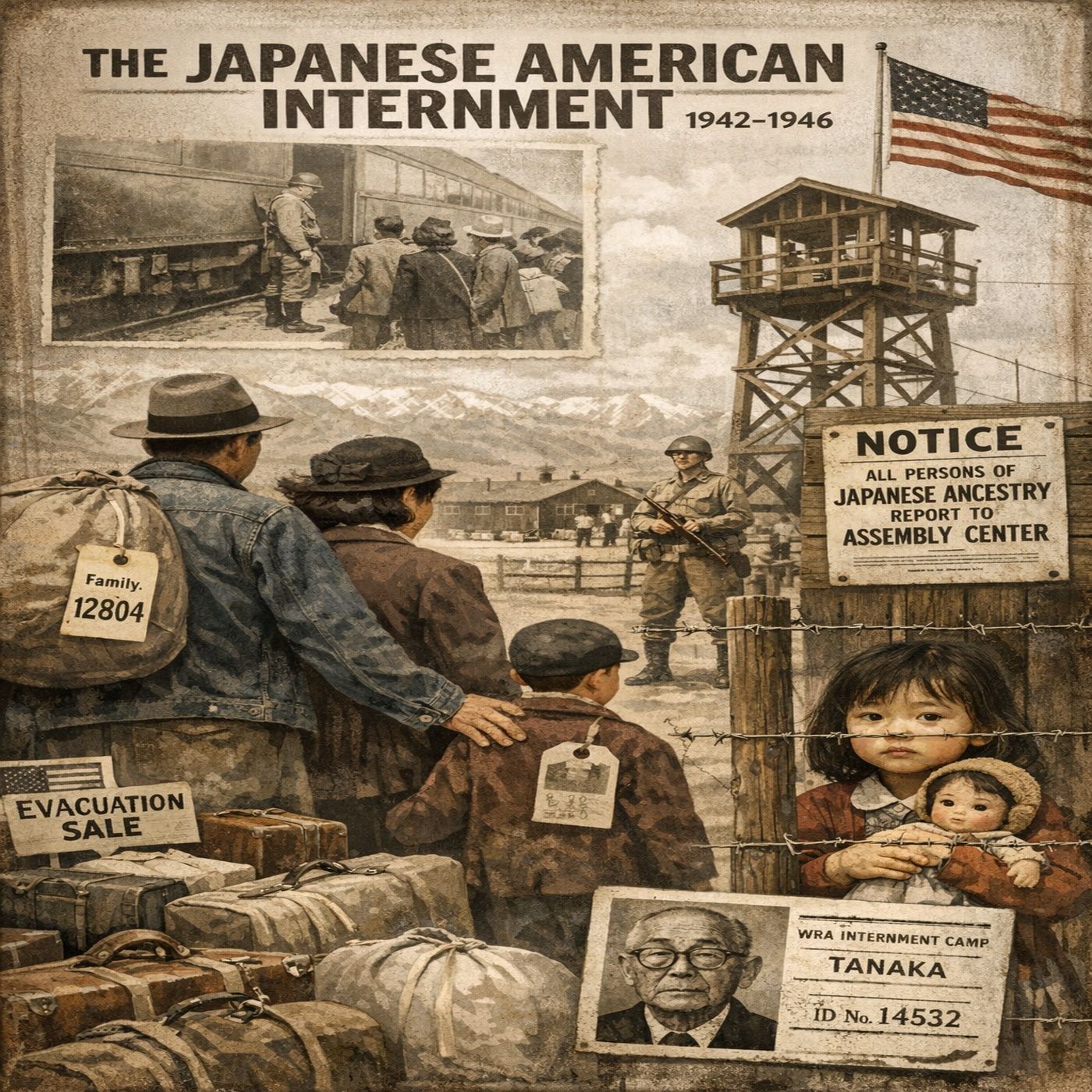

And tonight we're going to talk about one of the most disturbing chapters in American history, a chapter that should shake every single one of us to our core, A chapter that proves that constitutional rights are only as strong as the people willing to defend them, and that fear and prejudice can transform a democracy into something unrecognisable almost overnight.

Imagine this.

It's a cool spring morning in April of nineteen forty two.

You're an American citizen.

You were born here, your children were born here.

You've never committed a crime in your life.

You pay your taxes, your kids recite the Pledge of Allegiance every morning at school.

You own a small business, maybe a farm, maybe a fishing boat.

You've built something from nothing through years of backbreaking work.

And then comes the knock at the door.

A soldier stands on your porch, rifle slung over his shoulder.

He hands you a piece of paper.

You have seventy two hours to dispose of everything you own, everything you've spent your entire life building, your home, your business, your car, your furniture, your photo albums, your children's toys.

You can bring only what you can carry in your hands.

Where are you going?

You don't know for how long?

Nobody will tell you what did you do wrong?

Speaker 2Nothing?

Speaker 1Absolutely nothing.

Your only crime is the face you were born with and the ancestry you inherited from your grandparents.

This isn't fiction, This isn't some dystopian novel.

This is American history.

This happened right here on American soil to American citizens in the twentieth century, and over one hundred twenty thousand men, women, and children experienced exactly this nightmare.

They lost everything, their homes, their businesses, their farms, their boats, their dignity, their faith in the country they loved.

Some of them lost their lives, many lost their minds.

An entire generation was traumatized in ways that would echo through their families for decades to come.

And here's what makes this story even more disturbing.

It wasn't carried out by some rogue military command or gone mad.

It wasn't the work of a few bad actors.

It was official United States government policy, authorized by the President, upheld by the Supreme Court, supported by the majority of the American public, and executed with cold bureaucratic efficiency.

The United States of America, the self proclaimed beacon of freedom and democracy, the nation that would later condemn Nazi concentration camps with righteous fury, built its own concentration camps, and we put American citizens in them.

Let that sink in for a moment.

Tonight, we're going to tell this story in full.

We're going to examine how it happened, why it happened, what life was like inside those camps, how the government defended the indefensible, and how the survivors fought for decades to receive even a modicum of justice.

We're going to look at the heroes and the villains, the resistance and the collaboration, the lawsuits and the legislation, and we're going to ask ourselves a question that should trouble every American.

Could it happen again?

Because, as we'll see, the conditions that made this c atrocity possible have never fully disappeared.

This is the story of the Japanese American Internment, and it begins long before Pearl Harbor.

To understand how the United States government came to imprison over one hundred and twenty thousand of its own people, we have to go back decades before the first bomb fell on Pearl Harbor, because the internment didn't spring from nowhere.

It was the culmination of more than half a century of anti Asian racism that had been building, codifying, and intensifying on the American West Coast.

The first significant wave of Japanese immigration to the United States began in the eighteen eighties, following the Chinese Exclusion Act of eighteen eighty two.

That law, which banned Chinese laborers from entering the country, was America's first significant restriction on immigration, and it established a precedent that would prove catastrophic.

It demonstrated that Congress was willing to single out an entire ethnic group for exclusion based purely on their race.

Japanese immigrants, known as Essay meaning first generation, came to fill the labor void left by Chinese exclusion.

They worked on railroads, in mines, on farms, and in fishing industries.

They were willing to do backbreaking work for low wages, and like immigrants throughout American history, they dreamed of building better lives for their children.

But from the very beginning they faced hostility.

White workers saw them as competition, politicians saw them as convenient scapegoats.

Newspapers portrayed them as an invading horde, the so called Yellow Peril, threatening to overwhelm white Christian America.

In nineteen oh five, the Asiatic Exclusion League was formed in San Francisco with the explicit goal of extending Chinese exclusion to the Japanese labor unions.

Politicians and newspapers joined forces in a campaign of vilification.

The San Francisco Chronicle ran a series of inflammatory articles warning of the Japanese invasion and demanding action.

The pressure worked.

In nineteen oh seven, under the so called Gentlemen's Agreement between the United States and Japan, the Japanese government agreed to stop issuing passports to laborers seeking to emigrate to America.

It was a face saving arrangement that allowed both governments to avoid direct confrontation while effectively shutting the door on Japanese immigration.

But those already here weren't safe either.

In nineteen thirteen, California passed the Alien Land Law, which prohibited aliens ineligible for citizenship from owning agricultural land.

This was a legal euphemism targeting specifically the Japanese, since existing naturalization laws from seventeen ninety limited citizenship to free white persons.

The easy couldn't become citizens, so they couldn't own land.

It was that simple, and that deliberately cruel.

The Supreme Court made this ease more explicit in nineteen twenty two with the case of Takau Ozawa versus United States.

Ozawa had lived in America for twenty years.

He had graduated from Berkeley High School and attended the University of California.

He spoke English fluently, had raised his children as Christians, and had never once visited Japan As an adult.

He applied for citizenship and argued that he met every qualification except the racial one.

The Supreme Court unanimously rejected his petition.

Writing for the court, Justice George Sutherland declared that the term white person in the naturalization statute meant what it said, and that Japanese were not white.

It didn't matter how American you acted, how perfectly you assimilated how completely you embraced American values.

If you were Japanese, you could never become a citizen.

You would forever remain a permanent foreigner, a resident alien in the only country you knew his home.

This had cascading effects.

In nineteen twenty four, Congress passed the Immigration Act, which completely barred immigration from Japan and other Asian nations.

The message couldn't have been clear.

Japanese people were not welcome in America period.

But here's what makes this even more tragic.

By nineteen forty one, there were approximately one hundred twenty seven thousand people of Japanese ancestry living in the continental United States, mostly concentrated on the West Coast, and of these, roughly two thirds were nise second generation Japanese Americans born on American soil.

They were citizens by birth.

They had never known any other country.

Many of them spoke little or no Japanese.

They went to American schools, played American sports, listened to American music, and dreamed American dreams.

Their parents had been told they could never belong, But these young Americans believed in the promise of their country.

They believed that being born here meant something leave the constitution applied to them.

They were about to learn how wrong they were.

The attack on Pearl Harbor killed two thy four hundred three Americans and thrust the United States into World War II.

It was a genuine national trauma, a bolt from the blue that shattered any remaining illusions about American in vulnerability.

Fear and rage swept the nation, but on the West Coast that fear and rage quickly took a specific and ugly direction.

Within hours of the attack, the FBI began arresting Japanese community leaders.

By the end of December seventh, they had detained seven hundred thirty six Japanese nationals designated as dangerous enemy aliens.

By the end of the week, that number had grown to over twelve hundred.

These weren't random arrests.

The FBI and Naval Intelligence had been compiling lists of Japanese community leaders for years.

Buddhist priests, Japanese language school teachers, newspaper editors, business leaders, members of cultural organizations, anyone with ties to Japan or positions of influence in the Japanese American community.

They were taken from their homes, often in the middle of the night and held without charges and detention facilities.

Their families frequently had no idea where they had gone or if they would ever see them again.

For the Essay community, this was devastating.

These were their leaders, their elders, the people they looked to for guidance, and they had simply vanished into government custody.

But the arrests were only the beginning.

In the weeks following Pearl Harbor, hysteria gripped the West Coast.

Rumors of Japanese sabotage ran rampant, despite the complete absence of evidence.

There were reports of Japanese farmers planting crops and patterns to guide enemy aircraft, of fishing boat signaling submarines offshore, of domestic servants poisoning their employer's food.

None of these rumors were true, not a single one.

In the entire course of World War II, not one Japanese American was ever charged with espionage or sabotage, not one.

But truth didn't matter.

Fear had taken hold, and fear doesn't respond to facts.

Newspapers whipped up the frenzy.

Columnist Henry McLemore of the San Francisco Examiner wrote and I'm quoting here.

I am for the immediate removal of every Japanese on the West coast to a point deep in the interior.

I don't mean a nice part of the interior.

Speaker 2Either.

Speaker 1Hurt them up, pack them off, and give them the inside room in the bad lands.

Let them be pinched, hurt, hungry, and dead up against it.

That wasn't a fringe opinion.

That was a mainstream newspaper columnist advocating for the mass deportation and suffering of American citizens, and his readers largely agreed.

Politicians sensed which way the wind was blowing and rushed to outdo each other in their denunciations of the Japanese.

Congressman leland Ford of California demanded that all Japanese, whether citizens or not, be placed in inland concentration camps.

Note that he used the word concentration camps.

That wasn't a term imposed later by critics.

That was what they called them at the time, before the word became associated with Nazi death camps.

Attorney General Earl Warren, who would later become Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and author the landmark Brown Versus Board of Education decision, was then California's Attorney general.

He testified before a Congressional committee that Japanese Americans posed a unique threat precisely because none of them had committed any acts of sabotage.

Their very quietness, he argued, was evidence of a coordinated plan.

They were waiting for the signal to strike.

Think about the diabolical logic of that argument.

If Japanese Americans committed sabotage, that would prove they were dangerous.

If they didn't commit sabotage, that also proved they were dangerous.

There was literally no way for them to demonstrate their lawyer loyalty.

Their guilt was predetermined by their ancestry.

The military authorities on the West Coast added their voices to the chorus.

Lieutenant General John L.

DeWitt, commanding General of the Western Defense Command, made his views crystal clear in a report to the Secretary of War.

He wrote, the Japanese race is an enemy race, and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become Americanized, the racial strains are undiluted.

He went on, it makes no difference whether he is an American citizen.

He is still a Japanese American.

Citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty.

There are indications that these are organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity.

The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.

There it was again the same poisonous life guilt presumed because of race innocence transformed into evidence of conspiracy.

Meanwhile, Italian Americans and German Americans faced nothing comparable.

Stay tuned for more disturbing history.

We'll be back after these messages.

There were roughly six hundred thousand Italian born residents in the United States and about three hundred thousand German born residents.

Some faced restrictions and a small number were interned, but there was never any serious discussion of mass incarceration.

Why Because they were white, because they looked like real Americans, because their ethnic communities had political power and representatives who would fight for them.

The Japanese had none of those protections.

They were few in number, concentrated in a small geographic area, politically powerless, and visibly different.

They were in short perfect targets, and on February nineteenth, nineteen forty two, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order nine zero six six.

With a stroke of his pen, he set in motion one of the greatest violations of civil liberties in American history.

The text of Executive Order nine zero sixty six was deceptively bland.

It didn't mention Japanese or Japanese Americans by name.

It simply authorized the Secretary of War to designate military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded.

It delegated to military commanders the power to determine who could live where, and it established penalties for violating their orders.

This was legal slide of hand.

By not naming a specific group, the order avoided the most obvious constitutional challenges, but everyone understood who it was targeting.

Within weeks, the entire West Coast, including all of California, Western Oregon, and Washington and southern Arizona, had been declared a military zone from which persons of Japanese ancestry were to be excluded.

Did General de Witt wasted no time.

On March second, he issued Public Proclamation Number one, which established military areas one to two, covering the Pacific coast states.

Two weeks later, he created the wartime Civil Control Administration, the bureaucracy that would manage what the government euphemistically called evacuation, but which was in reality forced removal and imprisonment.

The process began with curfews.

All persons of Japanese ancestry were required to be in their homes between eight pm and six am.

They were prohibited from traveling more than five miles from their homes.

They were barred from possessing firearms, cameras, shortwave radios, or anything else deemed potentially useful to the enemy.

Then came the exclusion orders posted on telephone polls and bulletin boards in Japanese neighborhoods.

They informed residents that they had to report to assembly centers by a certain date.

The time frame was typically one to two weeks, sometimes less.

Families had mere days to dispose of everything they owned.

Think about what that meant in practical terms.

You have ten days to sell your house, your car, your business, your furniture.

Everyone knows you're desperate.

Everyone knows you have no choice.

Bargain hunters and profiteers descended on Japanese communities like vultures.

Farms worth hundreds of thousands of dollars sold for a few thousand.

Businesses built over decades went for pennies on the dollar.

Precious family heirlooms, irreplaceable photographs, treasured keepsakes, all of it sold, given away, or simply abandoned.

The government assigned storage facilities where evacuees could lead belongings they hoped to reclaim after the war.

Many did so, only to return years later and find that their possessions had been stolen, vandalized, or destroyed.

Some Japanese Americans tried to comply with the spirit of the exclusion orders by voluntarily relocating inland before the mandatory removal began.

A few thousand managed to move to states outside the exclusion zone, but they found that their new neighbors didn't want them either.

Governor Chase Clark of Idaho declared that Japanese were rats and threatened to throw them in concentration camps if they tried to settle in his state.

Nevada's attorney general announced that Japanese attempting to enter the state would be japped up and sent back where they came from.

There was nowhere to go.

The exclusion zone hemmed them in on one side, and hostile inland states blocked them on the other.

They were trapped, and so in the spring and summer of nineteen forty two, over one hundred and ten thousand men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from their homes and transported to assembly centers.

These were hastily converted fairgrounds, racetracks, and livestock exposition halls, nowhere near adequate to house tens of thousands of people.

Families were given numbers like inventory items or livestock.

They wore these numbers on tags attached to their clothing and their luggage.

They boarded buses and trains under armed guard, not knowing where they were going or what awaited them.

Mary Tsukamoto, who was removed from her home in flor in, California, later recalled the scene at the train station.

She said, when we got on the train, the shades were drawn.

The train was going, but we didn't know where we were going.

We didn't know where we were being taken.

It was one of the scariest parts of the evacuation because we didn't know.

No one told us anything.

We had no idea whether we'd be shot, whether we'd ever see our friends again, whether we were going to be put in prison.

These were American citizens being transported like prisoners of war, with no trial, no charges, and no idea of their fate.

And this was only the beginning.

The first stop for most evacuees was an assembly center.

These were temporary holding facilities while the permanent camps were being constructed in remote desert and swamp locations across the interior West.

The largest assembly center was at Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, California.

At its peak, it held nearly nineteen thousand people.

The Tan Foreign Racetrack in San Bruno housed over seven thousand.

Pomona Fairgrounds held about five thousand, Portland's Pacific International Livestock Exposition Facility, Payalop's Western Washington State Fairgrounds, Fresno's Fresno Assembly Center.

The list went on and on.

The conditions at these assembly centers were atrocious.

Santa Anita is perhaps the best documented because of its size and because several evacuees kept detailed diaries and later wrote memoirs.

When families arrived, they were assigned to housing.

For some, this meant hastily constructed barracks with tar paper walls and no insulation.

For others, it meant horse stalls.

Yes, horse stalls.

Families were housed in the same stone that had held horses just days before.

The stalls had been whitewashed, but that did nothing to cover the smell of manure that permeated everything.

Flies swarmed hay from the previous occupants, poked through mattresses.

The walls didn't reach the ceiling, offering no privacy whatsoever.

Families of five, six seven people crammed into spaces designed for a single horse mine.

Okubo, an artist who would later create a graphic memoir of her internment experience, described her quarters at Tanforon.

The stall was about ten by twenty feet and was our living quarters for the duration.

We were given army cots, mattresses, and blankets.

We were housed in a stable, the smell of which was overwhelming.

The mattresses were filled with straw, and the stalls still had horse hair everywhere.

We could hear the whispers and movements of families next door through the thin partitions.

Food was served in mess halls.

Long lines for institutional meals that were often inedible.

Rice was poorly cooked, vegetables were overcooked into mush.

Meat was scarce and of questionable quality.

Dysentery outbreaks were common due to unsanitary conditions.

Privacy was nonexistent.

Latrines had no partitions between toilets, showers had no curtains.

For the essay the elderly first generation immigrants who maintained traditional Japanese values of modesty and decorum, this was profoundly humiliating.

Many older women tried to use the facilities only in the middle of the night to avoid being seen.

Medical care was inadequate.

Hospitals were understaffed and undersupplied.

Women gave birth in these conditions.

People died.

At Santa Anita, evacuees established a makeshift cemetery, and yet within these hellish conditions, the Japanese American community tried to maintain some semblance of normal life.

They organized schools for the children, They created recreational activities, They publish camp newspapers, they held church services.

They found ways to maintain their dignity even as the government tried to strip it away.

But the assembly centers were only temporary.

After a few weeks or months, evacuees were loaded onto trains once again and transported to their final destinations.

The permanent camps the concentration camps.

The War Relocation Authority or WRA, established ten permanent camps in some of the most desolate locations in the American interior.

These weren't chosen for their hospitality.

They were chosen specifically because they were remote, inhospitable, and far from any strategic military installations.

Let me describe these camps and their locations, because the geography tells you everything about the government's intentions.

Manzanar, California, located in the Owens Valley at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

It was a desert of extreme temperatures bitter cold in winter, scorching heat in in summer, constant wind and dust storms that could last for days to Lake California, in the far northern part of the state, near the Oregon border.

It was built on a dry lake bed where temperatures plummeted in winter and dust clouds blotted out the sun.

Posting Arizona on the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

It was one of the hottest places in the United States, with summer temperatures routinely exceeding one hundred and twenty degrees fahrenheit.

Gila River, Arizona, also on a reservation, also brutally hot, with poisonous snakes and scorpions for neighbors.

Minnidoka, Idaho, on a sagebrush flat, where winter temperatures dropped well below zero and summer brought clouds of mosquitoes.

Heart Mountain, Wyoming at the foot of the Absaroka Range, where winter blizzards could dump several feet of snow and temperatures hit forty below.

Granada Amacha, Colorado, on the high plainanes of southeastern Colorado, where dust storms and rattlesnakes were constant companions.

Topaz Utah in the desert west of the Sevier River, where the alkali soil created a permanent white haze and respiratory problems were endemic.

Rower, Arkansas in the Mississippi Delta swampland, where mosquitoes, chiggers, and snakes made life miserable and humidity in summer was oppressive.

Jerome, Arkansas, also in the swamps, with conditions similar to Rowar.

These locations weren't selected despite their harsh conditions.

They were selected because of them.

The camps were intended to be unpleasant, they were intended to be inescapable, and they were intended to be invisible to the rest of America.

Each camp was laid out in a similar fashion, blocks of barracks surrounded by barbed wire fences, guard towers at regular intervals, manned by soldiers with machine guns pointed inward, lights that swept the grounds at night, armed patrols walking the perimeter.

The barracks were hastily constructed and poorly insulated.

They had gaps in the walls where wind and dust came through in winter.

Potbellied stoves provided inadequate heat.

In summer, the tar paper roofs absorbed the sun and turned the buildings into ovens.

Each family was assigned a single room, typically about twenty feet by twenty five feet, regardless of family size, a family of two got the same space as a family of eight.

The only furniture provided was a cot and a mattress for each person.

Everything else tables, chairs, shelves, room dividers.

Evacuees had to make themselves from scrap lumber.

Bathrooms were communal mess halls served institutional food to hundreds at a sitting.

The lack of family meals had a profound effect on Japanese American family structure.

Children ate with their friends instead of their parents.

Parental authority eroded.

The traditional family dinner so central to Japanese culture simply ceased to exist.

But the physical conditions, terrible as they were, might not have been the worst part.

The worst part was the psychological devastation of being imprisoned for no crime, stripped of your rights, and told in a thousand ways that you weren't really American despite what your birth certificate said.

What was daily life like in the camps?

It was monotonous, humiliating, and punctuated by moments of genuine trauma.

Work was available, but the pay was insulting.

Camp jobs ranged from kitchen help to teachers to doctors.

The wra classified jobs into three pay grades.

Unskilled workers earned twelve dollars per month.

Skilled workers earned sixteen dollars.

Professional and technical workers, including doctors and dentists, earned nineteen dollars for context, an army private earned fifty dollars per month.

The government justified these wages by noting that evacuees received free room and board as if imprisonment could be considered compensation.

Some evacuees worked as agricultural laborers on farms near the camps, helping to harvest crops that would feed the same nation that had imprisoned them.

Others worked in camp factories that produced goods for the war effort, again contributing to a country that denied their loyalty.

Education continued after a fashion.

Camp schools were staffed, initially by evacuee teachers and later supplemented by white teachers from outside, but the conditions were terrible.

Classes were held in barracks or mess halls.

Supplies were scarce, and what exactly do you teach children about American democracy when they're learning it from behind barbed wire.

One young evacuee later recalled being asked to recite the pledge of allegiance in class.

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible with liber liberty, and justice for all.

Stay tuned for more disturbing history.

We'll be back after these messages.

Liberty and justice for all.

While armed guards patrolled outside and barbed wired defined the boundaries of her world.

Religion continued as well, though the Buddhist community was particularly hard hit since so many Buddhist priests had been arrested in the initial roundups.

After Pearl Harbor, Christian churches, particularly Protestant denominations, organized to provide support to the camps.

Some white clergy came to live and work in the camps, one of the few groups of outsiders who showed genuine solidarity with the evacuees.

Despite everything, cultural life flourished in remarkable ways.

Artists created works that documented their experiences.

Poets wrote, musicians performed sports.

Leagues organized baseball and basketball games.

Evacuees created gardens in the desert, coaxing flowers to grow in soil that seemed to support nothing but sagebrush.

These acts of creation were themselves acts of resistance.

They were assertions of humanity and conditions designed to dehumanize.

They were declarations that, even in prison, even stripped of rights and property and dignity, the human spirit could not be entirely crushed, but the trauma was real and deep.

Suicide rates increased, depression was endemic.

Alcoholism, to the extent that alcohol could be obtained, became a problem.

Domestic violence, rare in Japanese American communities before the war, increased behind barbed wire.

The elderly suffered, particularly.

Many Issi had spent decades building lives in America.

They had started with nothing, worked harder than anyone should have to work, and created farms and businesses and families, And now it was all gone.

Everything they had sacrificed for stolen.

Some simply lost the will to live.

Children suffered differently, but no less profoundly.

Young children didn't fully understand what was happening or why.

Older children understood all too well that their country had betrayed them.

The message was clear, no matter how American you feel, no matter how loyal you are, you will never truly belong.

You are forever other, You are forever suspect.

This internalized shame would haunt many for the rest of their lives.

Psychologists who studied the long term effects of internment documented high rates of what would later be called post traumatic stress disorder.

Many survivors never talked about their experiences, even to their own children.

The silence itself became a form of trauma, passed down through generations.

In early nineteen forty three, the government decided to address what it saw as the problem of camp security and military manpower by administering a loyalty questionnaire to all evacuees over seventeen years of age.

This questionnaire would prove to be one of the most divisive and damaging episodes of the Internment experience.

The questionnaire was officially titled Statement of United States Citizen of Japanese Ancestry for citizens and Application for Leave Clearance for non citizens, but everyone called it the loyalty questionnaire because of two questions that would become infamous questions twenty seven and twenty eight.

Question twenty seven asked are you willing to serve in the Armed Forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?

Question twenty eight asked, will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, And for swear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government, power or organization.

These questions might seem straightforward, but they were anything but, especially for the essay for the elderly first generation.

Question twenty eight was a trap.

If they forswore allegiance to Japan, they would be left stateless.

Since American law prohibited them from becoming citizens, they would be people without a country.

For many, the answer was impossible.

They had no allegiance to the Japanese emperor to forswear, but they couldn't make themselves stateless either.

For the nise, the questions raised different problems.

How could they pledge to fight for a country that had imprisoned them without trial?

How could they swear loyalty to a nation that had stripped them of their constitutional rights.

Some felt that answering yes would validate the government's treatment of them.

Others felt that answering no would confirm every racist stereotype about Japanese disloyalty.

The questionnaire tore communities apart.

Families were divided, bitter arguments erupted in mess halls and barracks.

The government had demanded that imprisoned people proved their loyalty to their jailers, and no answer would be correct.

Those who answered no to both questions, or who refused to answer, were labeled disloyal and segregated at Toule Lake, which was converted into a maximum security camp for so called troublemakers.

By the end of nineteen forty three, Tuley Lake held over eighteen thousand people, making it the largest of all the camps.

Conditions at Tull Lake were the harshest of any camp.

Security was tightened, armed patrols increased, A stockade was built to hold prisoners within the prison.

Beatings and abuse by guards were reported.

A general strike in October nineteen forty three led to martial law and the deployment of additional troops.

Some of those segregated at Tule Lake eventually renounced their American citizenship, a decision they made under conditions of duress and psychological pressure that would have invalidated any contract in a court of law.

After the war, these renuncients faced deportation to Japan, a country many had never seen.

It took years of legal battles to restore their citizenship.

The Loyalty questionnaire accomplished nothing positive.

It didn't identify actual threats because there were none.

It didn't improve camp security because there were no security problems.

All it did was deep in trauma, divide families, and create a permanent record of government coercion that would haunt survivors for the rest of their lives.

The popular narrative of Japanese American internment sometimes portrays the evacuees as passive victims who accepted their fate without protest.

This narrative is false.

Resistance took many forms, from the dramatic to the everyday, from legal challenges to work slow downs to outright refusal to comply.

Three legal cases in particular challenged the constitutionality of internment and made their way to the Supreme Court.

The first was Hirabayashi versus United States, decided in nineteen forty three.

Gordon Hirabayashi was a senior at the University of Washington when the exclusion orders came.

A Quaker with deep pacifist convictions, he decided to challenge both the curfew and the exclusion order as violations of his constitutional rights.

He turned himself into the FBI and was convicted of violating both orders.

His case reached the Supreme Court, which ruled unanimously against him.

Chief Justice Harlan Fiskestone wrote that in times of war, the government could impose restrictions on specific groups if military necessity required it.

The Court deferred entirely to the military's judgment about that necessity and declined to examine whether the restrictions were actually justified by facts.

The second case was Yasue versus United States, decided the same day.

Minoru Yasue was a lawyer, a reserve officer in the United States Army, and the son of a respected community leader in Portland.

He deliberately violated the curfew to create a test case.

Like Hirabayashi.

He lost.

The Supreme Court again upheld the government's power to impose discriminatory curfews in wartime.

The third case was Korramatsu versus United States, decided in nineteen forty four.

Fred Kooramatsu refused to report for evacuation.

He had a white girlfriend he didn't want to leave.

He underwent minor plastic surgery to alter his appearance and tried to pass as Mexican American.

He was eventually arrested and convicted.

His case presented the Supreme Court with the most direct challenge to the exclusion order itself, and in a six to three decision, the Court upheld the order.

Justice Hugo.

Black wrote for the majority that while restrictions based on race were suspect, and subject to strict scrutiny.

The military necessity of protecting against espionage and sabotage justified the exclusion, But this time there were descents that would echo through history.

Justice Frank Murphy called the exclusion the legalization of racism and wrote that it fell into the abyss of racism.

Justice Robert Jackson warned that the Court had created a precedent that lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.

Those descents were prophetic.

The Kooramatsu decision would become one of the most criticized in Supreme Court history, condemned by legal scholars as a shameful abdication of judicial responsibility.

There was also a fourth case ex parte Endo, decided the same day as Kooramatsu.

Mitsuye Endo was a nise woman who had worked for the state of California before the war.

She filed a habeas corpus petition challenging her continued detention after she had been cleared as loyal.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in her favor, holding that the government could not continue to detain a conceitedly loyal citizen, but notice the timing.

The ENDO decision was announced on December eighteenth, nineteen forty four, one day after the w the War Department announced it was ending the exclusion.

The Roosevelt administration had known for months that the court was going to rule against continued detention of loyal citizens.

They timed the announcement to make it look like a voluntary policy change rather than a court ordered one.

Politics and public relations even in constitutional law.

Beyond the legal challenges, there was resistance within the camps.

At Manzanar.

Tensions over suspected informers led to a riot in December nineteen forty two.

Military police fired on the crowd, killing two and wounding at least ten others.

At postin a general strike in November nineteen forty two shut down the camp for days.

At Tule Lake, resistance was continuous and often violent.

There were draft resistors, young men who refused to serve in the military until their constitutional rights were restored.

The most organized group, the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee, argued that the government couldn't imprison their families as disloyal while demanding that they fight and die as loyal Americans.

Over three hundred NISSE across the camps were convicted of draft resistance and served time in federal prison.

And there was everyday resistance, the maintenance of dignity and community in the face of dehumanization.

Every flower garden planted in the desert, every baseball game organized, every graduation ceremony held behind barbed wire was an act of defiance.

It said, you may have imprisoned our bodies, but you cannot destroy our spirits.

While resistance took many forms, one of the most remarkable responses to internment was the military service of Japanese American soldiers who fought and died for the country that had imprisoned their families.

In January nineteen forty three, after months of debate, the War Department announced that NISE men would be allowed to volunteer for military service.

They would serve in a segregated unit.

Of course, the military wasn't ready for integration, but they could prove their loyalty on the battlefield.

The response was overwhelming.

Over twelve hundred men volunteered from Hawaii, where the Japanese American community had not been subjected to mass incarceration, and from the mainland camps from behind barbed wire.

Nearly three thousand young men stepped forward to fight for the country that had imprisoned them.

Think about that for a moment.

Your government has imprisoned your parents, your siblings, your grandparents.

It has stripped you of your rights, taken your property, and confined your family to a desert prison camp surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers.

And when that same government asks you to risk your life in its defense, you say yes.

Speaker 2Why.

Speaker 1The reasons were complex.

Some believed that military service would prove Japanese American loyalty and lead to better treatment of their families.

Some saw it as a way to escape the camps.

Some genuinely believed in the American ideals that their country had failed to live up to.

And some were motivated by the Japanese concept of geary obligation and on debt, feeling that they owed something to the country of their birth despite its betrayal.

The four hundred forty second Regimental Combat Team, combined with the one hundredth Infantry Battalion from Hawaii, became the most decorated unit in American military history for its size and length of service.

Their motto was Gopher broke, a gambling term from Hawaiian dice games, meaning to risk everything, and risk everything they did.

The four hundred forty second fought primarily in Europe, in Italy and France, they sustained extraordinary casualties.

In October nineteen forty four, they were assigned to rescue the Lost Battalion, a unit of Texans surrounded by German forces in the Voges Mountains.

The rescue succeeded, but at horrific cost.

To save two hundred eleven Texans, the four hundred forty second suffered over eight hundred casualties, including one hundred eighty four dead.

By the end of the war, the four hundred forty second had earned over eighteen thousand individual decorations, including twenty one Medals of Honor, with more awarded posthumously in later decades, fifty two Distinguished Service Crosses, five hundred sixty Silver Stars, and over nine thousand Purple Hearts.

These men fought with the ferocity born of having something to prove.

They could not be accused of disloyalty, They could not be called cowards.

Whatever racism America threw at them, they answered on the battlefield, but their heroism did not free their families.

While they bled and died in Europe, their parents remained behind barbed wire.

Some soldiers received letters from home describing the dust storms, the inadequate food, the humiliation of prison life.

Some learned that parents or grandparents had died in camp while they were fighting overseas, and when they returned home as decorated heroes, they often found that their families had nothing left.

The farms were gone, the businesses were gone, the homes were gone.

They had given everything for a country that had taken everything from them.

Stay tuned for more disturbing history.

We'll be back after these messages.

There's a famous photograph of Sadau Munamori's mother receiving his posthumous Medal of Honor at the Mansanar camp.

Her son died throwing himself on a grenade to save his fellow soldiers.

She received the medal in a prison camp surrounded by barbed wire, honored for her son's sacrifice, even as she herself remained a prisoner.

That photograph tells you everything about the contradictions and cruelties of this chapter in American history.

By nineteen forty four, the Tide of war had turned decisively in the allies favor.

The threat of Japanese invasion, which had never been realistic, was now laughable, and the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, which had never been justified by military necessity, was becoming increasingly indefensible.

Within the government, some officials began pushing for an end to the exclusion.

The War Department's own assessments concluded that the Japanese American population posed no security threat.

Secretary of the Interior Herald Ikeys, whose department included the wra urged Roosevelt to end the camps, but nineteen forty four was an election year.

Roosevelt was running for an unprecedented fourth term.

His advisers feared that releasing Japanese Americans before the election could cost votes on the West Coast, so the decision was postponed.

After Roosevelt won reelection in November nineteen forty four, the exclusion was finally rescinded.

On December seventeenth, nineteen forty four.

The War Department announced that the exclusion orders would be lifted effective January two, nineteen forty five.

Japanese Americans would be permitted to return to their homes, but return to what The camps began closing, some immediately, others over the next year and a half.

The last tool Lake didn't close until March nineteen forty six, almost a full year after Germany surrendered and six months after Japan did.

Some evacue's had to be essentially pushed out.

They had nowhere to go and no means to get there.

The government provided each release to vacuee twenty five dollars and a one way train ticket.

Speaker 2That was it.

Speaker 1After two to four years of imprisonment.

After losing homes and businesses and life savings, they were given twenty five dollars and told good luck.

Many returned to the West coast to find their properties vandalized, stolen, or sold.

Farms that had been left in the care of neighbors had been mismanaged or stripped of equipment.

Stored belongings had disappeared.

Communities that had once been home now felt hostile and unwelcoming.

Some returnees faced violence.

Shots were fired into homes, arson destroyed property, Threatening notes appeared on doorstet no japs wanted signs were posted in store windows.

Rebuilding took decades.

Many families never recovered the essay.

The elderly first generation were often too old and too broken to start over.

Many lived out their remaining years in poverty, dependent on their children.

The American dreams they had sacrificed everything for reduced to ashes the nise.

The second generation bore the burden of reconstruction.

They worked multiple jobs, they put their children through school, they rebuilt businesses from nothing, and many of them never talked about what had happened.

The shame of imprisonment, even though they had done nothing wrong, was too great to bear.

Silence became a survival mechanism.

This silence had profound effects on the Sanse, the third generation, who grew up knowing something terrible had happened, but not understanding what.

The trauma passed down through generations, manifesting in anxiety, depression, and a diffuse sense of shame with no clear source.

After the war, the government wanted to forget that the camps had ever existed.

There was no official acknowledgment of wrongdoing, no apology, no meaningful compensation.

The Japanese American Claims Act of nineteen forty eight allowed former evacuees to file claims for property losses, but the process was deliberately difficult.

Claims required extensive documentation, which many evacuees no longer had.

Government bureaucracy delayed processing for years, and in the end, the total amount paid out roughly thirty seven million dollars to approximately twenty six thousan five hundred claimants, represented only about ten cents on the dollar of actual losses.

The legal challenges continued as well.

Gordon, Hirabayashi, Fred Kooramatsu, and Minoru Yasue had all served their sentences and gone on with their lives, but their convictions remained permanent marks on their records legal validations of their unjust treatment.

Then, in the nineteen eighties, researcher Peter Irons discovered documents in the National Archives that changed everything.

These documents revealed that government attorneys had suppressed, altered, and destroyed evidence in the original wartime cases.

They showed that intelligence reports contradicting claims of military necessity had been deliberately concealed from the Supreme Court.

In other words, the government had lied the cases that had sent these men to prison and validated the internment of over one hundred twenty thousand people had been based on fraud.

Armed with this evidence, Kooramatsuhirabayashi, and Yasue filed petitions for korum nobis, a rare legal procedure to vacate convictions based on fundamental errors or government misconduct.

In nineteen eighty three, Koramatsu's conviction was vacated by Judge Maryland Hall Patel, who declared that the case stands as a caution that in times of international hostility and intactaganisms, our institutions legislative, executive, and judicial must be prepared to protect all citizens from the petty fears and prejudices that are so easily combated.

Hirabayashi's conviction was vacated in nineteen eighty seven.

Yasui died in nineteen eighty six before his case could be fully resolved, but the koram Nobus petition had already demonstrated the government's misconduct.

These legal victories were symbolically important, but they didn't help the survivors.

For that, the Japanese American community would need congressional action.

The campaign for redress had been building since the nineteen seventies.

Japanese American activists, many of them Sansei, who wanted to understand what had happened to their parents and grandparents, began pushing for an official investigation and formal apology.

They faced resistance not only from the government but from within their own community.

Many Nisi felt that speaking up would only draw unwonted attention that the Japanese conscient of Chicataganai meaning it cannot be helped, counseled acceptance rather than protest, but the activists persisted.

In nineteen eighty, Congress created the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate the internment and its effects.

The Commission held hearings across the country where survivors testified about their experiences.

For many, it was the first time they had ever spoken publicly about what had happened.

The testimony was devastating.

Elderly survivors broke down in tears describing events that had occurred forty years before.

They spoke of the shame, the humiliation, the loss, and the lasting psychological damage.

For the first time, their stories became part of the official record.

In nineteen eighty three, the Commission issued its report, titled Personal Justice Denied.

Its conclusions were unequivocal.

The promulgation of Executive Order nine zero sixty six was not justified by milli military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it detention, ending detention, and ending exclusion were not driven by analysis of military conditions.

The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race, prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership, not military necessity, not security concerns, just racism and fear and cowardice.

The commission recommended a formal apology and individual payments of twenty thousand dollars to each survivor.

It would take five more years to translate those recommendations into law.

The Reagan administration initially opposed monetary compensation.

Many in Congress argued that the government shouldn't pay for past wrongs, but the Japanese American community persisted, joined by civil rights organizations and veterans groups and religious denominations.

Finally, on August tenth, nineteen eighty eight, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of nineteen eighty eight.

The law acknowledged that a grave injustice had been done to Japanese Americans.

It formally apologized on behalf of the people of the United States, and it authorized payments of twenty thousand dollars to each surviving ATTORNEE.

Reagan, speaking at the signing ceremony, said, what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor.

For here we admit a wrong.

Here we affirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.

The first redress checks were mailed in nineteen ninety, forty eight years after the internment began.

Many survivors had already died.

Many more would die before receiving payment, But for those who lived to see it, the acknowledgment mattered as much as the money.

Their government had finally admitted what they had always known, that they had been wronged.

The Civil Liberties Act of nineteen eighty eight provided a measure of closure, but it did not heal all wounds.

The effects of internment continued to ripple through the the Japanese American community to this day.

Psychologists have documented the intergenerational trauma passed from survivors to their children and grandchildren.

The sanse and Yonsey the third and fourth generations often struggle with issues they can't fully explain anxiety, depression, a sense of not belonging, difficulty trusting institutions.

They inherited trauma that was never fully processed because it was never fully discussed.

Economic effects persist as well.

Studies have shown that Japanese American families lost in today's dollars between two and five billion dollars in property, income and opportunity.

The twenty thousand dollars paid in redressed was a fraction of actual losses.

Entire family fortunes accumulated over generations were wiped out.

The wealth that would have been passed down simply didn't exist.

There are cultural effects too.

Traditional Japanese American communities were destroyed by the internment and never fully rebuilt.

Before the war, Japanese Americans lived in concentrated neighborhoods japan towns where cultural traditions could be maintained and passed down.

After the war, many dispersed to avoid the discrimination that came from visibility.

The dispersal accelerated assimilation, but at the cost of cultural continuity, and there are ongoing debates within the Japanese American community itself.

How should internment be remembered, how should it be taught?

Is it better to focus on resilience and recovery or to dwell on injustice and trauma.

Should the community's energy be directed toward commemorating the past or engaging with present day issues.

These debates intensified after September eleventh, two thousand and one, when many Japanese Americans saw disturbing parallels between the treatment of Muslim and Arab Americans and their own history.

The surveillance of mosques, the detention of immigrants without charges, the rhetoric of disloyalty and suspicion directed at entire communities, it felt terribly familiar.

Japanese American organizations have been among the most vocal critics of post nine to eleven policies targeting Muslim communities.

Survivors of the internment have spoken at rallies and hearings, warning that the same fears and prejudices that led to their imprisonment could lead to similar injustices today.

The Internment, they argue, is not just history, it's a warning, and the legal precedent of Koamatsu has never been formally overruled.

In twenty eighteen, in the case of Trump versus Hawaii, the Supreme Court finally repudiated it, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing that Kooramatsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and, to be clear, has no place in law under the Constitution.

But even this repudiation came in a case that upheld a different form of exclusion, president Trump's travel band targeting predominantly Muslim countries.

The dissenters in that case, particularly Justice Sonya Soto Mayor, argued that the majority was deploying the same logic of deference to executive claims of national security that had enabled Kamatsu in the first place.

Justice Jackson's warning echoes still the President lies about like a loaded weapon.

What should we learn from this shameful chapter of American history?

The lessons seem obvious, but our failure to heed them suggests they need repeating.

First, constitutional rights are only as strong as our willingness to defend them, especially for the vulnerable and unpopular.

The Japanese American community in nineteen forty two was small, politically powerless, and visibly different.

When fear swept the nation, no one with power stood up for them.

The President signed the exclusion order, Congress funded the camps, the Supreme Court validated the imprisonment.

Every branch of government failed.

This wasn't a rogue operation.

This was official policy, approved at every level.

It was democracy choosing oppression.

And that's what makes it so disturbing.

We can't blame a dictator or a rogue general.

We did this to ourselves, we the people.

Second, claims of military necessity should always be viewed with skepticism, especially when they target specific ethnic or religious groups.

The government claimed that Japanese Americans posed a security threat.

It was a lie.

There was no evidence of disloyalty.

Intelligence agencies knew this, Military commanders knew this, but the lie served political purposes, so it persisted.

Every generation since has faced similar claims.

Communists are infiltrating our institutions, Refugees are terrorist sleeper cells, immigrants are invaders.

Each time fear is used to justify suspending rights.

Each time we later discovered that the threat was exaggerated or invented, and yet we keep falling for it.

Third, racism doesn't disappear, it goes dormant.

The anti Asian racism that enabled internment had roots going back decades.

It had been encoded in law through exclusion acts and alien land laws.

It had been validated by Supreme Court decisions.

It was always there, waiting for a crisis to bring it back to the surface.

We've seen this again and again.

After nine to eleven, hate crimes against Muslims and Sikhs spiked during the COVID nineteen pandemic.

Hate crimes against Asian Americans surged again as the same old Yellow Peril rhetoric resurfaced in the form of the China virus and Kung flu.

The virus was just the trigger.

The racism was always there.

Fourth Once rites are suspended for one group, they can be suspended for others.

The legal doctrines developed to justify Japanese American internment didn't disappear after the war.

They were available to be used again.

The executive authority claimed by Roosevelt was expanded by later presidents.

The judicial defference shown by the wartime Supreme Court became a template for future courts reluctant to second guest claims of national security power once seized is rarely relinquished.

Precedents, once set are rarely undone.

Every exception to constitutional protection becomes a tool for future exceptions.

And fifth, ordinary people can enable extraordinary evil.

The soldiers who guarded the camps, the bureaucrats who processed the paperwork, the neighbors who bought Japanese property at firesale prices, the politicians who whipped up fear for electoral advantage.

None of these were cartoon villains.

They were ordinary Americans doing what they believed was right, or at least what was expedient.

That's the most disturbing lesson of all.

This wasn't done by monsters.

It was done by US, people who considered themselves good Americans, by people who went to church on Sunday and loved their children and believed in the Constitution.

They did it because fear and prejudice are powerful, and because doing the right thing often requires courage that most people don't have.

The last surviving residents of the internment camps are now in their eighties and nineties.

Soon there will be no one left who remembers what it was like to be loaded onto a train and shipped to a desert prison for no crime at all.

But their stories live on in memoirs and oral histories, in museums like Mansinar and Heart Mountain, in documentary films and academic studies, in the activism of their children and grandchildren.

Japanese Americans have worked tirelessly to ensure that this history is not forgotten.

They have built monuments, They have organized pilgrimages to the former camp sites.

They have testified before Congress.

They have spoken in schools and churches and community centers.

They have insisted that America rem what it did, because memory is the only real defense against repetition.

We would like to believe that it could never happen again.

We would like to think that we've learned our lesson, but the conditions that made internment possible have never fully disappeared.

Fear is still weaponized, Racism still festers, politicians still scapegoat vulnerable communities for political gain, and constitutional rights are still treated as luxuries that can be suspended in times of crisis.

Every generation must choose whether to uphold the promises of the Constitution or abandon them when they become inconvenient.

Every generation faces tests of its commitment to liberty and justice for all, not just for those who look like us, not just for those who pray like us, not just for those who were born here, for all The people imprisoned behind barbed wire in those desert camps were Americans.

They were our fellow citizens, they were our neighbors, and we failed them.

We failed them not because we were uniquely evil, but because we were human, Because fear and prejudice are human.

Because the courage to stand up for the rights of the unpopular is rare and precious and easily overwhelmed.

The only way to honor their suffering is to ensure it never happens again, not to Japanese Americans, not to Muslim Americans, not to any group targeted for who they are rather than what they've done.

That's the challenge that this history leaves us.

That's the question that echoes across the decades.

When fear comes calling, when politicians point fingers, when the drums of hatred begin to beat, well, we have the courage to say no.

The people in those camps couldn't answer that question for us.

They could only show us what happens when the answer is wrong.

The rest is up to us.

This has been disturbing history, reminding you that the past is never really passed, and that the arc of the moral universe doesn't bend towards justice.

On its own.

It bends because people push it, because ordinary people find extraordinary courage, because we refuse to look away from the darkest chapters of our history, and we resolved to write a different future.

Until next time, take care of each other and remember never again means never again for anyone.

Speaker 2My sad, your ski, health, God, a taste fun, your shame, m sie, war child and calm fun.

You better know from moon is out.

Now you're gonna hear money, home, home, lard, sky red ice, KNKEI love father, my drinks.

You're not.

You'll see the come and full came and full you.

You better from movies out.

Now you're gonna hear my ho ho ho.

Speaker 1You You better run now.

Speaker 2Slason, Now you're gonna hear my cat