Episode Transcript

In March nineteen eighty four, coal miners in Britain walked out on strike against the pit closure plan of Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government.

Miners, wives and other women started support groups up and down the country which were instrumental in helping the workers hold out for nearly a year in an iconic dispute which changed Britain forever.

This is working class history.

Now, before we get into the main episode, some eagle eared listeners may remember hearing our episode about women in the minor strike before.

Now, like all of our original episodes, it was basically made up of raw audio from our interview so there wasn't any narrative to fill gaps or explain context and kind of draw the story together into a whole.

So, in addition to working on new episodes for you, we're also going back over our earliest episodes to re we edit and release them in the new narrative format we use for all of our later episodes.

So the interview audio today is going to be the same quality as before, but they'll be added narrative with better quality audio to explain things and hopefully tell the story in a more cohesive manner.

So we hope you enjoy it.

As a reminder, our podcast is brought to you by our Patreon supporters.

Our supporters fund our work and in return get exclusive early access to podcast episodes without ads, bonus episodes every month, free and discounted merchandise and other content.

For example, our supporters can listen to both parts of this double episode now.

So if you can, please join our community and help keep our collective history of struggle alive.

You can learn more and sign up at patreon dot com slash working class history link in the show notes.

We're working on a podcast mini series about the MINUS strike from the perspective of MINUS themselves at the moment, So for today, I'm just going to give a very brief bit of the historical background.

At the beginning of the nineteen eighties, coal miners in the National Union of Mine Workers NUM were the best organized and most militant section of the working class in Britain.

As detailed in our episode eighty one, miners had held successful nationwide strikes in nineteen seventy two and nineteen seventy four, when they won big pay increases and brought down the Conservative government of Edward Heath.

With the election of Thatcher in nineteen seventy nine.

Her Conservative Party were determined to reshape the UK from a more social democratic state with high levels of state ownership and where working people were organized and had some economic power, to a more neoliberal one where there was more widespread private ownership and there was a more atomized working class which wasn't able to exert its own power.

Thatcher's strategy was to isolate different groups of workers and defeat them one by one.

The most important group of workers they would need to beat were the miners, who up until that point had shown that they were willing and able to confront the state and win.

To do this, the government planned to provoke a strike at a time which would be favorable for them, so shortly after their election, when winter was almost over, coalstocks were high and energy use was low, because both the nineteen seventy two and seventy four strikes took place at the height of winter, when coalstocks were depleted and energy use was high, and most electricity at the time was from coal fired power stations, so they would announce a plan to close pits and layoff miners, to which the nun would have to respond with a strike.

The government's hope was that they'd then be able to sit out the strike until the miners and their families, not earning any wages, were basically stafved back to work.

To this aim, the government stoppard enough coal and coke to last six months and slashed state benefits that would have been available to strikers and their families.

But if the government thought that the workers would be forced back to work within six months, then they would turn out to be deeply mistaken, perhaps because they didn't factor in the support for miners which would come from their wives and other women.

Speaker 2I was a member of the Labor Party, quite active in politics, and I was working at the local council offices in the housing department, and my husband was a plumber who worked full time and we had two children.

Speaker 1This is Heatherwood, who was living in Easington, County Durham in the northeast of England and later became chair of the Easington Women's Support Group.

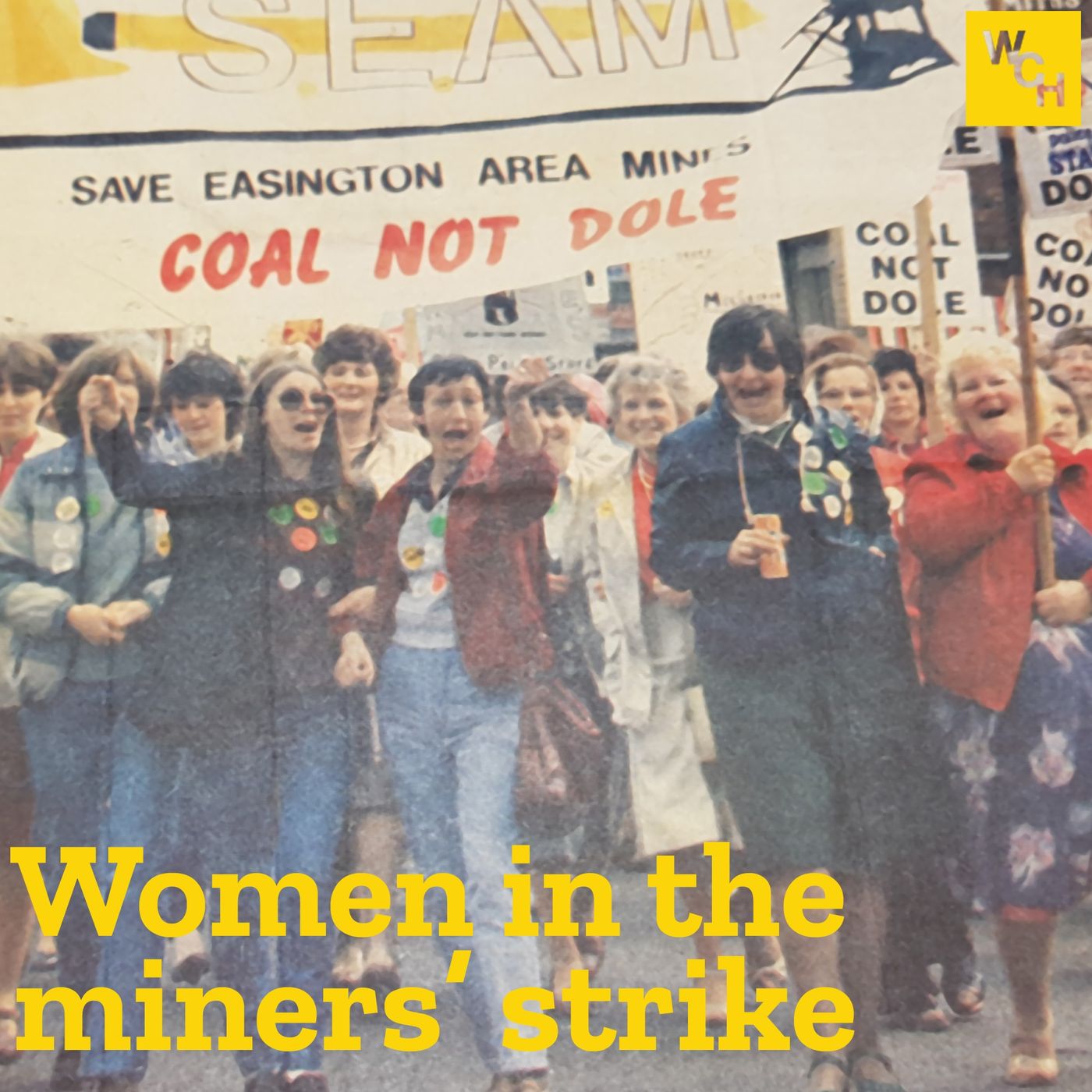

Speaker 2In the eighty three, I was chair of the constituency Labor Party and we had heard rumors that pitts were going to clause in our area and our district, so we decided that we needed to inform people and we set up the constituency had an open public meeting and we established how many people were interested in having to fight for the community and fight to say of jobs, and we set up an organization called Save Easington Area Mains.

We call it Scene for Shot and it was that same year eighty three when we had what were then the biggest rally of MINUS banners outside of the Doha Big Meeting, and it was in Easington.

Speaker 1This big meeting is also known as the Durham Minus Gala, a legendary gathering of miners and their supporters which has taken place almost every July since eighteen seventy one.

Speaker 2PATCHA that amazing and from there we just went on giving our public informations to what the cost to our villages would be if the mines.

Speaker 1Caused Around the country.

Miners and their supporters stepped up organizing campaigns against pit closures, and in October nineteen eighty three NUM delegates voted to fight all pit closures other than ones where coal at the pit had been exhausted.

In March nineteen eighty four, the government announced that collieries in Yorkshire would be closed and work that immediately walked out on wildcat strike.

They were soon joined by a majority of MINUS nationwide, and within a few days the NUM called an official national strike.

Right away, activists like Heather began supporting the strike and raising funds to help the workers.

Speaker 2Of course, along in early eighty four came the strike and my own village, the pitch voter to come out on strike.

My husband and I said, well, two things.

We wanted somebody to fight the government.

The second one and the main one was we want our community to remain as it is close in this community who help each other.

So we decided that we'd give five pounds a week to the fund.

But as with everything in my life, it was like topsy.

It grew and grew and grew, and I decided a couple of weeks into the strike, I mentioned at the scene meeting that we needed to get at the women in the mining communities because without the women, the men would not stay out on strike because, contrary to public beliefs, MINUS wives are not held down the rule and if their wives had said you go back, with the how to go back.

So what I said was all the literature that was coming out to the villages then to the houses as minus was from the union, so it was more than likely to be read by the men and not the women of the house.

So we got together three of us, Dave Temple, Brian Blanchard himselves in our house would put together a letter for every woman in Easington district.

We had to do that because there nobody had a list of where each miner lived in the district, so we just decided to live at every house.

We had a meeting of women in the council offices of Asent in village.

The council chamber was absolutely full with women.

It was wonderful to say that so many wanted to be part of and wanted to support and stand beside the husbands and or the brothers or the fathers.

And from there we formed the first Apartmentroup, which was in Easington Colliery.

Speaker 1In mining communities up and down Britain, other women, particularly miners wives, also started organizing groups to support the strike.

They were raising money, setting up soup kitchens and gathering and distributing parcels of food for strikers and their families.

The same happened in Easington.

Speaker 2I went to the miner's lodge at Easington, just to let them know what we were doing, and just as in a side, the two of us women had to sit outside of the meeting while the men decided whether a woman could come into the lodge meeting.

And after about half an hour the debate had gone on and came out and said we could enter.

And I remember saying too, while I'm coming into the secretary of the lodge.

Once I'm in, I'm not going back, you know, And he last, and it was true, because we went from strength to strength.

But we set up from there.

We went to all the different communities in Easington District and some beyond and had set up support groups there, and I attended lodge meetings to let the managers know what each of those groups were doing.

We ended off.

We set up in Easington District fourteen support groups which either provided food that by with a meal each day or food parcels where they couldn't provide a meal, but the would raise funds for food parcels.

And I'm pleased to say that I can now speak of my own community, Easington.

We had our free cast within Easington Collie Workman's Club and for a year we fed people one mile a day for five days a week, and during the school holidays, I wrote to the county council to ask you for good yuse yeah the school kitchens, and I'm police to say they said yes.

So that made life so much easier.

For instance, my mother was an ex cook for school meals, so she knew the school kitchen as well.

And for the six weeks we were able to provide a really good mail for those children, and the mom and dad used to pay for and my mom would make a dessert for the children, so the adults didn't go desert for that six weeks, but the children got looked after.

We raised funds from all over the world and in fact, in Babish Museum there is a section that's called the head of Wood collection and that has every photograph for every press cutting, every notice that we sent out to people about the striking, giving them information on where you could go to get this family other with regards especially to school uniforms after some holidays, so it was a busy year.

Christmas we did all sorts of Christmas and we kept going for a year, and I'm proud to say I was part of it.

Speaker 1Women all over the country were involved in support groups, organizing and also taking to the streets.

In May nineteen eighty four, up to twelve thousand women from support groups marched through the streets of Barnsley against the pit closures.

Speaker 2Were out actively working in the groups.

There were no more than a dozen women in each of the fourteen groups.

But the important thing to remember is it wasn't just the women who came out and did something in the support groups that kept the strike going.

It was the women in the houses where they had to keep the household going on very very little money, and that wasn't an easy task.

So you're I mean you talked about every miner's wife was involved and was active in the sense that they motivated their husbands to stay on strike.

The may have gone and stood to where the pigot buses off on a morning, or to welcome them back on a night.

So they were active even though they weren't out making meals being organized as far as fundraisings concerned.

But I have to say the women in the support groups, a lot of them weren't politically motivated.

When they started.

It was to save their communities and save their futures.

For their children and their grandchildren, so it was very difficult to talk to them about the political side of the strike.

But as the weeks went on and there was sort of drip said about what was happening, they started to ask questions, and they started to want to board a place where there was political discussion and to want to be on the pickup lines.

And some of them actually spoke in public meetings which they had never ever done before, gone on television and being interviewed.

Helped to put together a book, The Last quarterse of Spring, which was poems and songs and short stories written by the women of Easington.

They were approached by Northern Arts to have a right to be in residence.

Margaret Heine came and she wrote a play Not by Bread Alone about the minor strike, and that was performed around the Northeast.

Then it went to London, then it went to the Lamplish Theater in Germany and Oldenburg University.

So they were big things from women who came out to make a mail for a few hundred people.

They'd ended off organizing all this themselves.

Speaker 1Fantastic involvement in the strike started to have a transformative effect on the lives of many of the women.

Speaker 2Definitely.

It is as I say, At the beginning, they wanted to make males, which is very important.

But as time went on, they wanted to know more of what was going on with the strike, the political side of the strike, and they wanted to go and stand on the picquet line and fight for the jobs in the community.

That way, they didn't necessarily want to go and speak on television or in meetings.

They did it in the end because I was doing it all and I said, it's just too much.

You're going to have to have your names and I have to manage your turn.

You do it, and thank god they did.

One woman who was one of the quietest people you wished to meet.

She ended off with one of the biggest rallies in Middlesbrough, with Tony Ben on the platform with her and all she said was I work for British call im a cleaner, and I'm on strike.

My husband's a miner, he's on strike.

We have two children.

Can you help us now?

The crowd erupted.

It was obvious that woman wasn't used to being where she was.

But after that that woman went to Greenham Common.

She came on rallies with US.

I was on the pickup line.

She wasn't frightened to speak up.

Speaker 1Greenham Common was a women's peace camp set up in protest at US cruise missiles being stationed at the Berkshire Royal Air Force Base.

Speaker 2That made all the difference there.

So instead of coming out and doing a job and then going home quietly, you know, sort of it's a bit like they changed the world but hadn't realized that had so they just went back to what they were doing.

Where in the strike it continued on, it grew.

Some of them went on to be well.

Julianna Heaven she was.

I think she's been made twice.

She's from the South Heaton support group when she hadn't really been involved in politics before the strike, and she's still involved.

You know, the people like her who've continued on the fight.

There's women who went on to parish councils or who just became more active in the community, to involuntary work, fundrais and for whatever organizing.

And I think that's that's important to know that those women, although there were doing it before, they did things very quietly.

Now the shout more and said look this is what we do and you better write it all down.

It needs to be written for history.

Speaker 1In mining communities, women's activism contributed to a shift in family and gender and ynamics.

As a note here for non UK English speakers, bends is another word for children.

Speaker 2I think it was strange at first.

Nobody ever really said anything, but it was strange to something because it was out of the ordinary for them to do.

I mean, the hour hours, it was just something that happened.

I was always out doing something politically, but it was something that changed.

Now.

Got no doubt that it would have been difficult because of the men.

This is where it comes in the masculinity to me, because it's not even the masculinity, just the fact that they would normally be at work, but now we they had time on the hands.

So they were taking the children to school, they were staying at the school gates to pick the bends up.

You know, they were housekeeping because a lot of the women went and got part time jobs factories and in shops, so they were now looking after the household.

So there's boundary of being some because I mean, if it was in our house, I'd be saying with John, couldn't do it as well as our cou so there would be a grow there part from having no money.

So there's boundary of being.

And I know as we went into the strike, as the months went by, the women in our support group in Eavenson, that and fakeful.

Now they were getting quite despondent and the money was getting really short and bills were coming in, so tempers were getting fraught.

And I remember there were a few barneys just within the women, and I'd said, I'll tell you what when we meet every Thursday, which we did to organize the following week, just when you're at home, right down, how are you feeling about something, or just come and speak on it at our next meeting.

And they did that, and that's where and then there was some really humding arguments.

But what I said was, you do that in the meeting and then you walk out.

The cause is bigger than you and your argument with whoever.

We united when we walk out that job, and do you know what worked?

It actually worked.

And from there they did write songs, stories, poems and they were published.

So out of all that, Agro came something that was really good.

But the women were stronger, they worked better together and they put together a book which they would never have done.

Probably, So yes, I think there's been arguments.

I've got no doubt about that, because it must be strange you're changing roles completely.

They were divorces bought in the may and everybody was united, all stood.

Speaker 1Together despite the match.

How the image many people have of mining towns, women there have always played active roles in their communities.

Speaker 2I think that's a fallacy because, as I say, the women have always when you look back in the history of mining communities, it's always been the women who've come out to get things done.

For instance, we needed when I was a little girl, I can remember there were no indoor toilets and bathroom so it was the women who took to the streets and blockaded the men road to the pit with their pushchairs and prams and whatever to fight for the core board to fit bathrooms and indoor toilets to the Polly properties and the one.

Speaker 1Women also played important roles in previous big industrial disputes, particularly during the General Strike of nineteen twenty six.

Speaker 2I think because mine has come across as there were very strong men and the women don't necessarily come out and say, oh, we do this.

We do that.

It doesn't mean the we'ren't doing it, that we're doing it.

In the home, they looked after the money, the husband tipped the money up, They looked after all the bills and there were very few who didn't do that.

Speaker 1In addition to providing material support for the strike in terms of money and food, many women joined picket lines to help physically prevent scam replacement workers getting to work, including in Easington.

Often, mind bosses would make it difficult for strikers to effectively pick it, so they would mark mine property with yellow lines to allow space for scabs to get in.

Then if mine is trying to pick it cross those lines, they could be fired.

But the women weren't employed by the mines, so they couldn't be disciplined or sacked.

Speaker 2I used to go down every morning to my children down and as for instance, for August twenty fourth, nineteen eighty four, Easington was taken over by police and that was because on the evening of August twenty third, Peace Merchant Tory MP was on the news saying why is it Dome Constabulary.

It can't get one man in at Easington pit because there had been bring them to the village more or less in you know, you've tried and allowed just go home.

But the next morning after peace, Merchant said that I went to take my children to school and our village green, which is enormous, was with black It was full of place.

And we got further down the road and then with a police called, and so I had to stop and tell them where we were going.

And I said, I'm going to be mom to drop the children off, and he said, okay, you can go, and just as we were passing before I got the window wound up.

The younger son shouted, but ma'm you didn't tell them we were going to the picket lines first, and I could have killed him.

But that was me going to the picket lines.

But there were other women who went, and they went a lot more than maybe because I was working.

They went and stood and gid.

One of the things we always say is they were arrest women because we were shouting scab.

So we put half the women at one side of the road and half of the other, and one half shouted scaf and the others shouted ab.

So we've got it in news eventually, and we couldn't be arrested.

My mum was on the picket line the day the first man went back at Asington Colliery, who lived in Asington, and she saw the women would tell her maybe because I wasn't there.

She said, I can't shout scab, so she said she shouted, come on, bunny, lad, don't go back in, and as it happened, he didn't go.

And my mamma always says it's because she just shouted, come on, body, lad, don't go in.

But yeah, it was life changing.

I think paper funother side of life, and started to want to organize the pickets rather, you know, try to organize the men and get as much activity as we could along by the pit.

Speaker 1There were reports of some male and UM members turning women away from picket lines, believing that they were dangerous and no place for women, but still women continued to turn up.

Some women organized themselves into groups of flying pickets, traveling to working pits in places like Nottingham Sure where a majority of miners were scabbing on.

The strike responded to women pickets with arrests, violence, and frequently verbal abuse, which was often sexualized.

Speaker 2It was name calling that was the biggest thing I can't think.

I mean, I know there were women in different parts of the country, and there were a couple of women from Heaven Lawrence Vnson being born who were arrested.

But in Easington, it was name calling.

It was trying to put you down as a woman.

You know, it was weighing ten pounds notes in your face or in van windows as they were passing you.

You made to feel like, I'm very frightened.

I was frightened.

I'm no shame in saying that.

I was frightened because I'd seen what they could do, and I'm still frightened because I'd seen what the state can do.

They were an armored the state, and if the state can do that to people who weren't at risk to the state, what else can they do?

So so frightening.

Speaker 1Police were also happy to arrest and frame pickets and disguise their identities in order to brutalize strikers and their supporters.

Speaker 2They used to stand at the pitchyard outside the pit wall and there would be linked arm in arm and every now and again they would open up and just take one lad through and then they would arrest him and he would be charged with God knows what need be had caught, and then he'd be in prison and never done anything in his life.

You know, that keeps the en people's keep saying that kind of happened.

But I saw with my own eyes, you know, there was somebody last week said to me, all the reason the police didn't have numbers on the jackets was because they were torn off by the miners.

Where August the twenty four I watched them come into my village and they came in with no numbers on their jackets.

Also, there was no fighting, no problems as such, you know, no hand and fighting at that point in Easington.

That was not So it's a lie, it's a fallacy.

It's a misinterprets.

And what went on to say that the k me in with those numbers on the jackets they did.

Speaker 1Well, that's it for part one.

We'll conclude the story in part two.

You can listen to that now by joining us on Patreon and accessing loads of other great exclusive content.

It's only support from you, our listeners, which allows us to make these podcasts.

So if you appreciate our work, please do think about joining us at Patreon dot com.

Slash Working Class History link in the show notes.

Otherwise, the episode will be out for everyone else next week.

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about UK minus struggles, check out our episodes twenty seven to twenty nine about queer support for the strike, and episode eighty one about the strikes in nineteen seventy two and seventy four.

If you join us us on Patreon isn't an option for you at the moment, Absolutely no worries, but please do tell your friends about this podcast and give us a five star review on your favorite podcast app.

Thanks to our Patroon supporters for making this podcast possible special thanks to Jazz Hands, Fernando Lopez, a Haida, Nick Williams, and Old Norm.

Music in these episodes is courtesy of the Easington Colliery Band.

Learn more about them on the links in the show notes.

This updated episode was edited by Tyler Hill with original editing by Jesse French.

Thanks for listening and catch you next time.