Episode Transcript

Hi, and welcome back to part two of our double episode about the fight against the polt Taks in the UK in the late nineteen eighties and early nineties.

If you haven't listened to part one yet, I'd go back and listen to that first.

Speaker 2Alamatina happenalta ah be la child, be la child, the larchild chow chow Alamatina I'm penala.

Speaker 1Before we get started, we just wanted to remind you that our podcast is brought to you by our Patreon supporters.

Our supporters found our work and in return get exclusive early access to podcast episodes without ads, bonus episodes every month, free and discounted merchandise and other content.

So our supporters can listen to an exclusive bonus episode about this topic with more information.

So if you can, please join us and help us preserve and promote our history of collective struggle.

Learn more and sign up at patreon dot com slash working Class History link in the show notes.

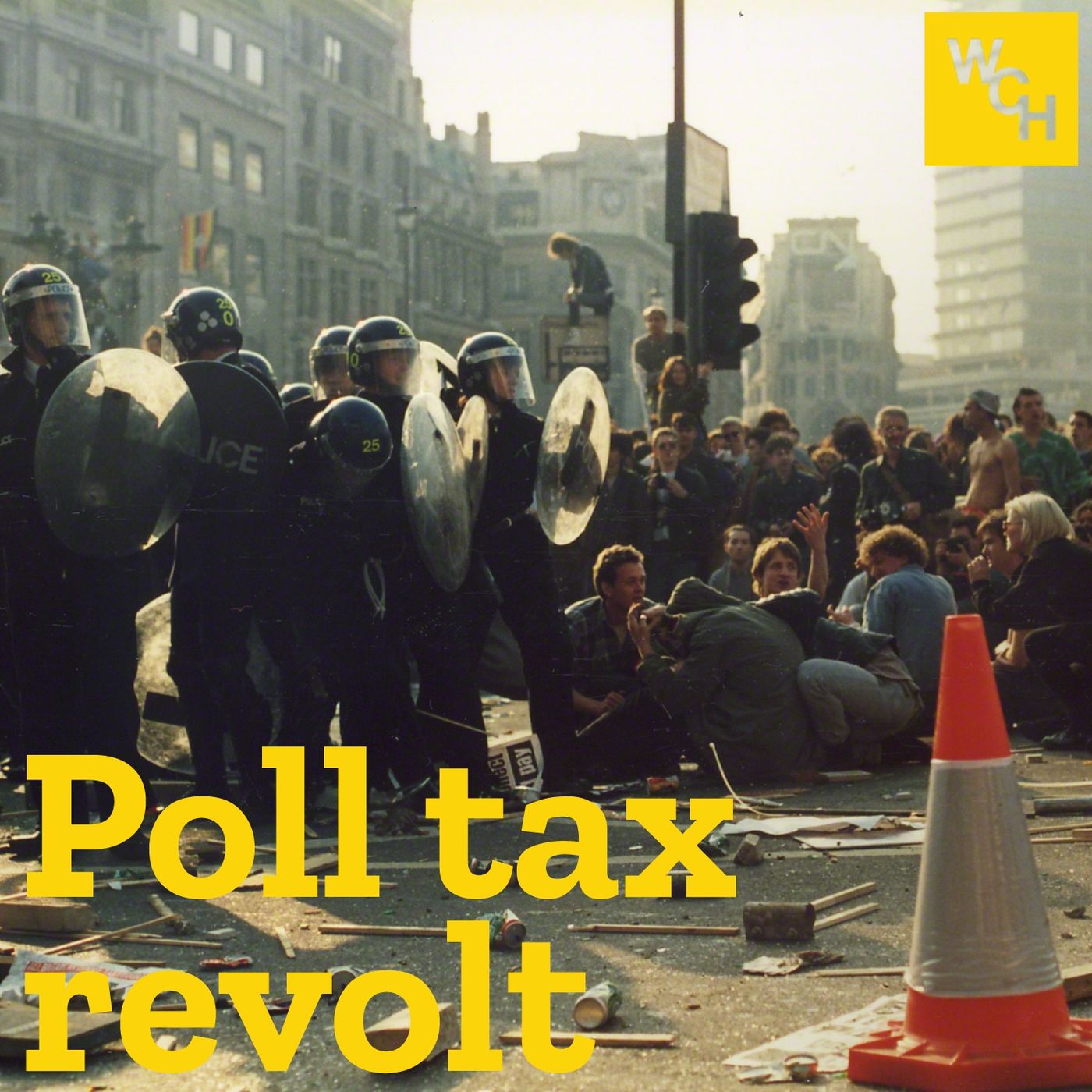

We left off last week on the thirty first of March nineteen ninety after a police attack on tens of thousands of anti poll tax demonstrators backfired, resulting in heavy rioting on the eve of the introduction of attacks on the first of April.

Speaker 3So everybody, all the police, the media, the government all laid into the demonstrators.

They all immediately blamed the devonstrates as the Labor Party.

Everybody headed in for the devonstrades.

Speaker 1As a reminder, this is Dave Morris of the Tottenham Anti poll Tax group in London.

Speaker 3They thought this was a very strong, well roots said, determined movement that was determined to defy the law, so that in their eyes, the establishment, you know, everyone was a radical, but we're talking about millions of people.

They thought they could just attack, insult the intelligence of the whole anti pol tax movement.

And I remember speaking to a journalist TV cameraman at Travalga Square during the whole battle, and you wants to know what do you think about what's happened, and I gave my opinion.

I said, you know, you're only put the opinions down that the media want to put over.

He said, yeah, that's true, because I wasponed to seventeen people, you know, seventeen people on this issue, and nobody is willing to condemn the demonstrators.

Yeah, and of course what will appear in the news that evening ordinary member the public or demonstrators will say, oh, it's all some troublemakers or something.

Speaker 1Indeed, in the wake of the riot, the British press was incensed and called on members of the public to turn on the writers.

They worked with police to identify suspects and appealed to readers to quote hunt the rioters and quote shop them I eat informing them to the police.

The People newspaper, for example, displayed a mugshot of one man it described as a quote swarthy Latin or Mediterranean type with a high forehead end quote, who was wanted for allegedly throwing a scaffold pole through the front window of a police car like a spear.

But the propaganda didn't.

Speaker 4Really work, and the reality was there was massive support for people's right to defend themselves and against the police and against the governments.

Speaker 3Because the tax was so hated.

But also I think people realized that this was a provocation.

I think the aim of the police and the government was to try to split the movement into respectable and and you know, they thought it would work.

It worked in terms of all the official establishment media and whatever slamming the demonstrators, but also Militants or the All Britain Federation main organizers, who of course wanted to stay in the Labor Party because that was their long term strategy of trying to take over the Labor Party.

They said that they would organize an investigation and name names of the people behind the violence.

Speaker 1As a reminder, Militant was the largest revolutionary left group in the UK at the time.

Under huge pressure from the press, two Militant activists, Steve Nally and Tommy Sheridan, who were both leading officials within the All Britain Anti Pol Tax Federation known as the FED, appeared on news programs to condemn the rioters.

The general line adopted by Militant at that time was that around two hundred and fifty individuals quote intent on causing trial end quote, had sabotaged the march.

Sheridan said the FED quote condemned it totally end quote, and Nally said that they would quote conduct an internal inquiry to try to root out the troublemakers, which will go public and if necessary name names.

Speaker 5End quote.

Speaker 3So the organizers of the demonstration were backed into a corner where they were condemning the demonstrators for defending themselves against police violence.

This completely outraged everybody within the anti Poul Sax movements, and the organizers of the demonstration had no contingency plans, no legal defense contingency pairs if anyone was arrested, no solicitors' numbers, no advice on what to say if people were arrested.

No, you know, there was no pre thinking about what advice people might need.

But also there was clear going to be no follow up because they were actually condemning people for defended themselves.

Speaker 1Now, in the end, this promised internal inquiry never happened, and no officials in the FED did name any names.

But with the help of the media, the police started identifying more suspects from the riot.

In particular, they wanted to catch three hundred people they claimed had been caught on film committing serious crimes.

Now, in reality, all they needed to do was catch people who looked like those three hundred people, and they used the riot as a pretext to raid large numbers of homes, particularly of people involved in local anti pol tax groups.

Officers smashed down doors, attacked activists, ripped flats and houses apart, and seized things like address books, pamphlets, and leaflets.

Dave and others in the grassroots three D network felt they had to support those arrested.

Speaker 3Some of us involved with the three D Network, who of course were involved with the demonstration, we said we've got to do something immediately because I think three hundred and forty people got arrested at the demonstration, but one hundred and fifty got arrested in the following weeks.

There was this hysteria in the media and police raids, particularly around London, but all over the country.

There was clearly going to be a really quite serious crackdown against the anti pol tax movement, and we had to defend everybody that was arrested.

So within forty eight hours or something, we started having small meetings.

You know, we didn't know who had been arrested, where they were being kept, so we had to start going to all the police stations courtrooms to track people down, to give them information and contact numbers of solicitors.

It was a real uphill battle which could have been much better prepared for before the event.

So we organized a defendants meeting pretty soon after the demonstration.

About sixty people who had been arrested came along and we decided to set up the Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign.

Speaker 5This became really important.

Speaker 3So the aim of the campaign support those arrested, get them legal advice, raise money so that people could if they were being held in jail or whatever without bail, they could get visits.

But maybe as importantly, to get the whole anti pol tax movement to commit to supporting the Trafalgar Square Defendants campaign.

The All Britain Federation didn't like kids, they didn't want an independent national body, and I think they called their own meeting which only two defendants turned up to, and basically they had to abandon their kind of attempts to create something in petition with the Travago Square Defendance campaign, and gradually over the following months, every federation of anti poll tax groups signed up to support the Travago Square Defendants campaign, which was really important.

Speaker 1Legal support for arrested participants is a vital but often neglected part of any social movement which wants to be successful, and the Trafalgar Square Defendants campaign set a great example of how to organize it.

Speaker 3It wasn't just moral support, it wasn't just money, it wasn't just it also involved the whole movement in tracking down people that had been defendants, witnesses to what had happens and to keep the movement united was the most important success of the Trafago Square defendants campaign.

So the attempt by the authorities to divide and rule by splitting people into respectable and radical was countered effectively, so the whole movement remained united.

I was heavily involved in that Travance Square Defendant's campaign for the following year.

In fact, actually we also as a campaign was supporting anybody that was arrested on local protests, as well as Pavada Square getting the whole movement to take a principal position that they would support anyone arrested in their local areas or even jailed, because some people were being jailed for non payment eventually, and we thought it was very, very important that the whole movement supported those who were, you know, subject to police or bailiff's action for being part of the movement.

Speaker 1The Defendant's campaign put on dozens of benefit gigs to raise money, and they put together a team of solicitors.

This lawyer's group helped do things like gather police video evidence and pass it onto the campaign, which then went through them, looking for relevant evidence for different defendants and editing particular portions for use in different people's trials.

The campaign also on advice sessions about prison and held weekly meetings, mailing them minutes out to all of the over two hundred and fifty defendants they were supporting.

The Trafalgar Squared Defendants campaign liked the movement against the poll tax itself was also infiltrated by undercover police.

You can learn more about that in the bonus episode with Dave, available for our supporters on Patreon on the link in the show notes.

Some defendants did end up getting convicted or taking plea deals where they pled guilty to lesser offenses than what they were initially charged with in order to get lighter sentences, but the campaign and their lawyers did help numerous defendants get off At trial, multiple people ended up being found not guilty or having their cases dismissed because they were able to prove that the police blatantly lied and falsified evidence.

A mister Hanni was acquitted after police statements were proven to have been falsified and also later edited to match his description rather than the actual perpetrator of the offense.

Duras in the court room burst out laughing when they saw the police notes, which originally described a man with a shaved head.

After Hanni was arrested who didn't have a shaved head, the officer crossed that out and instead wrote in close cropped hair.

One defendant, a former miner named Michael Conway, was charged with violent disorder.

He did admit throwing rocks at police, but he stated that he did so in order to protect the crowd from violent police attacks.

He was acquitted by the jury.

The day after the riot, the poll tax officially came into force, and so the most crucial phase of the campaign began non payment.

Actually following through with refusing to pay the tax would be the most difficult and frightening part of the campaign for participants, so we asked Dave how the movement tried to repair people for taking this step.

Speaker 3It was really important to get out mass information, encouragements, advice, support, neighborhood by neighborhood across the whole country, so that people felt part of something.

It wasn't just something you read about in the media or had a few celebrities or leaders.

It was something that had a mass, grassroots character.

So obviously we encourage people not to pay.

People started, you know, challenging the bills saying they'd not received them or or they weren't the person that named on the bill.

If they didn't pay the bill, they got a summons to attend court, which would result in a court ordering them to pay.

Speaker 5So there was a whole block for court's.

Speaker 3Kind of campaign, you know, because normally if people don't pay their local council rates or tax, they wouldn't attend court.

They'd just wait until they got an order through the post.

So we were saying, well, let's go in en mass to the courts.

So hundreds were turning up.

Because of the scale of it.

Local councils saying harringey, they might try and deal with three thousand court cases in bulk on a day, but if someone turns up then they had to have a proper hearing with that person.

Are you that person?

Do you owe this money?

You know, why haven't you paid its?

So we were advised to turn up.

We were advising people how to challenge the bills basically take as much time assumingly possible.

Speaker 5And this was happening all over the country.

Speaker 1This was causing problems with the courts because there had never been the need to have so many court cases around non payment before.

As some examples, Bristol City Council issued one hundred and twenty thousand summonses to people in Leeds, it was one hundred and ten thousand people, with similar numbers in other cities.

Councils were regularly issuing summonses to three thousand people or more on a single day, which of course wouldn't be possible in a courtroom in the alloted time.

Demonstrations were held by local antipol tax groups on court dates as well.

In Warrington, for example, in June nineteen ninety one thousand protesters took over with the court, forcing all cases to be postponed.

In Southwark.

In London, fifteen hundred protesters appeared at court, overwhelming the police.

They refused to budge until the court agreed to adjourn all five thousand of its cases.

Speaker 3So the entire court system was kind of clogged up and really struggling, I mean seriously struggling.

It's something like fifty percent of the summons is you know, that were challenged or that people turned up then they couldn't enforce them.

Speaker 1Local groups also worked with sympathetic lawyers to train their members to support non payers in court, which they were able to do in some cases.

As Mackenzie friends a role in which non lawyers can provide advice and assistance to defendants.

We discussed this role in more detail in episodes eighty three to eighty four of our podcast about the Angry Brigade and their trial.

A poll Tax Legal group was established and in total over one thousand people in England and Wales were trained in poll Tak's law by the movement.

They also produced dozens of easy to read leaflets and bulletins, as well as a book full of tips on how to disrupt or delay court proceedings from anything like asking for water, demanding to see ID documents of everyone in the court, or even having people set off fire alarms in the building.

Defendants were also helped by the incompetence of local councils who didn't have previous experience dealing with this kind of situation.

Medina Council on the Isle of Wight, for example, sent out court reminded notices using second class stamps.

This meant that by the time they arrived, defendants didn't get the advanced notice period they were legally entitled to, so the court throughout all nineteen hundred cases and the Council had to go back to the drawing board at this point.

It's worth stressing that the movement against the poll tax was overwhelmingly a working class movement.

Speaker 3The majority of people who weren't paying were people who couldn't pay, so the big slogan was can't pay, won't pay.

Really that was the core of the movement.

It wasn't necessarily the core of those who regularly attended the local groups.

I would say it was a predominantly working class movement, and radical activists probably had an influence beyond their numbers, but the power of the movement was a whole mosaic of informal networks in pubs, in streets, in workplaces, which should never be underestimated.

It's not just the people who've signed up to become a member of a campaign, but if it's a genuinely mass campaign, it kind of reaches very very widely through informal conversations and word of mouth.

Speaker 5And so when we had five hundred street reps at.

Speaker 3One point in Haringey, it's not necessarily that everybody in that street was feeding back to that street rep.

But somehow they became a conduit for you know, people thought they were expert just because oh, you're the street rep for the campaign, so you must know everything about the polls.

You know, maybe they didn't know that much about it, but they'd volunteered to at least give out leaflets or something, so you know, and then people felt linked into that kind of coordinated network.

But the strength of it went far beyond the formal organization.

And I would say ninety five percent of the non payers were people who just couldn't have fall to pay.

I mean, for working class people not paying a bill, it's quite a big step because you know there's going to be enforcement down the line.

Yeah, so you know, often you hear people calling there should be rend strikes, and there should be this, and people shouldn't pay their electric bills because they're too much.

You know, this is quite a challenge for people.

I mean, obviously a lot of people just can't pay anyway, but then they get into debt and that leads a serious trouble.

Speaker 5But this was for the first time, possibly.

Speaker 3In history, you know, there was a collective non payments widespreads so that people felt confident that they can take parts.

Speaker 1In some areas, local newspapers published lists of the names of non payers, trying to shame them into paying.

This strategy backfired spectacularly because organizers used them to contact nonpayers to advise them of their rights, and some people who hadn't been included on the lists wrote into papers to complain that they were proud nonpayers, upset that their names had been left out.

In addition to the courts, local councils used bailiffs to try to enforce payment of the poll tax.

Speaker 3The next stage is that people would be sent orders that if they didn't pay within six weeks or something, bailiffs would come.

Bailiffs were like, you know, official thugs that would come around if somebody has a debt and basically say we're going to if you don't right now on the doorstep.

You know, we're going to come in and take your goods, take your computer, take your whatever.

You know, it wasn't computers at that stage, but you know, we will take them and then we will sell them.

The council will sell them to raise money to pay your debts.

Speaker 1The situation with bailiffs was worse in Scotland than elsewhere.

In England and Wales, councils can only send around the bailiffs after courts have granted liability orders and then they can only enter your home if you let them in or if they find an open window or door.

But in Scotland, sheriff officers can be sent to seize property without court hearings and they're allowed to break into your house to seize your property and auction it off.

Speaker 3So there was a whole period of advising people about the powers that bailiffs have if you don't let them in, if you don't open your door, and they can't get in their power lists, so don't talk to them, don't collaborate.

There were sort of owned trees and mobilizations if bayliffs were in an area, because they would try to do you know, like fifty homes in one go in a particular area.

People would have whistles and try to mobilize people because probably a majority didn't want to pay the pull tax.

Even if they felt they had to pay, they were still against it, so people would mobilize and if bailiffs were spotted an area, people would make loud noises and gather at houses that were being targeted.

This is quite a systematic, extensive solidarity movement at the grassroots in Scotland.

Speaker 1Because of the different legal situation where bailiffs could break into your house, physical defense of homes was much more important.

The first attempt of sheriff to raid a property in Glasgow was at the home of Jeanette McGinn.

Over three hundred people assembled outside her house and the sheriff never even ended up trying to get inside.

Local antipol tax unions issued guidance advising people facing visits from sheriffs to move their cars away from their homes and move possessions to friends houses.

Sometimes they would help them move the goods as well.

In Edinburgh, organizers set up a group called Scumbusters with cars and CEBE radios to monitor bailiff's movements and mobilized defense of homes.

Activists in Scotland also held multiple occupations of sheriff's offices.

In one instance, protesters demanded that sheriff's abandon an auction of goods seized from a local woman One Missus pattern, and this was successful, with sheriffs abandoning the case.

Other groups around the UK used tactics like telephone trees and spied on bailiff companies to identify their car number plates, which would be circulated in local areas.

Some cars had their tires slashed, and sometimes entire towns were blockaded.

In the tiny village of Bishop's Lydard, with a population of fewer than three thousand people, one day, significant numbers of residents took the day off work, organized themselves into small groups, and built barricades, setting up checkpoints into the village to stop vehicles and ask them about their business.

Speaker 3You know, I'm not saying it happened in every case, but it happened enough that the Pultex.

Speaker 5Was becoming unenforceable.

Speaker 3I when we're talking about millions were getting summons is millions were getting bailiffs notes.

Speaker 5Hundreds of thousands were getting visits from bailiffs.

Speaker 1Protesters were demonstrating outside the homes of owners of bailiff companies, and many of the companies were getting into financial difficulty, some of them going bankrupt.

Bailiffs are only paid on a commission basis, so they only get a cut of depths they're able to recoup.

So if they don't recoup a debt, they don't get paid, and they were not doing a great job of recovering debts.

In Bristol, for example, in a whole year, bailiffs had only managed to get fifty four thousand pounds from over one hundred and twenty thousand people who weren't paying.

And in Scotland, a survey by Labor Research showed that after forty thousand visits to seize property from homes, sheriffs hadn't managed to sell the property of a single person.

In Scotland, the government resorted to trying to deduct money directly from the bank accounts of non payers.

So organizers invised nonpayers to withdraw money from the four major banks and instead used building societies or smaller banks.

Bank bosses complained to councils about this, and so this option was never implemented in England or Wales.

Another option for councils trying to get their money was wage arrestment, taking money directly from people's pay packets or state benefits, but this wasn't very successful either, firstly because councils had to get a legal judgment beforehand.

Secondly, if they managed to get that, there were limits on how much could be deducted from someone's wages or benefits.

So even if deductions occurred, they still weren't enough to cover the poll tax.

And finally, many people refused to comply with the process.

In order to deduct wages, councils had to find out who people's employers were, so they sent people reforms demanding to know where they worked.

Now, technically it was a criminal offense not to fit in the form, but the punishment was only one hundred pounds fine, which of course was considerably lower than the poll tax.

People were already refusing to pay, so in Scotland, after a couple of years of the tax, councils had only managed to implement wage arrestments for fourteen thousand people and a little under fifteen thousand seizures directly from people's bank accounts.

Now, this might seem like a lot until you realize that over a million people in Scotland were refusing to pay.

So the only other stick authorities had to compel payment was imprisonment.

Speaker 3And then the next stage was if the bailiffs couldn't enforce the debts and they were threatening people with jail, you know, and there was ways of the heads out of a court hearing disrupt those you know, you can always pay at the last minute if of all else fails.

Speaker 1So as the last resort.

If people could afford the tax, then they could always just decide to pay it.

But a good number of people refused to pay on principle and were imprisoned, and of course those who just couldn't afford to pay were jailed as well.

Speaker 3I mean, some of the Trafalgar Square defendants had gone to jail, but we were also helping them challenge the police, you know, account of what had happened.

And many people who were arrested on anti poltex protests at Travalgar Square or elsewhere were being found not guilty by juries.

Juries were generally sympathetic, but in local areas some people did.

Speaker 5Go to jail for non payment.

Speaker 3So it was a complex, constantly developing movements.

Speaker 1The first person to rend with imprisonment was a seventy four year old pensioner in Northampton called Cyril Mundin.

He was arrested by bailiffs in October nineteen ninety and threatened with fourteen days in prison if he didn't pay his tax.

Local residents occupied the office of the City treasurer in protest, holding him inside for over an hour.

In the end, a tabloid newspaper paid his tax and he wasn't jailed.

The first person actually jailed was a man called Brian Wright in Grantham, who got a three week sentence.

Hundreds of people wrote him letters and cards of support, and hundreds more demonstrated outside his prison.

Council officers were flooded with hate mail, and activists also visited politicians, including his local Member of Parliament MP and the government minister.

Following the intervention of his local MP, Wright was allowed visitors in prison every day and he got released after just two weeks.

Speaker 3You know many people did go to jail, Nott sure how many?

I heard one estimate of two thousand people.

Speaker 1We'll be right back after these messages.

If you want to listen to our podcast without ads, join us on Patreon, where you can also listen to an additional bonus episode with more information about Dave's life, activism and connection with our current Prime Minister, Keir Starmer.

Support from our listeners on Patreon is the only way we're able to devote the time and money it takes to make this podcast.

You can learn more and join us at patreon dot com slash Working Class History link.

In the show notes, chaos in the taxation system was mounting, and so grassroots campaigners wanted to up the pressure.

Speaker 3The unease began to grip the Conservative Party and there were mutterings against Margaret Thatcher, I mean all around the world.

The Trafalgar Square battle had got massive publicity and that undermined the kind of Thatcher, kind of iron lady kind of propaganda about the ladies not for turning and all that kind of stuff.

So really the last gas, apart from the local struggle and non cooperation campaign, was the Trafalgar Square Defenders Campaign was calling for another national demonstration because Conservative MPs were calling for demonstrations in central London to be banned or at least the police have the power to do so, which they've never had.

So we said it's really important to get back to a mass protest in central.

Speaker 1Love The National Federation didn't want another mass protest.

They wanted a symbolic march of just seventy five people across the country, consisting almost entirely of members and supporters of militant but the Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign and numerous local antipol tax groups and federations insisted that they wanted a mass protest which would also rally support for those in prison on the twentieth of October nineteen ninety and the FED decided that it wouldn't oppose such a move.

They've talked in detail about the debates and preparations for this protest and what happened afterwards in the bonus episode for this one, available for Outpatriot supporters.

The day before the protest, supporters of the campaign protested in fifteen countries around the world, including Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Austria and the US, and protesters in France occupied the British consulate.

On the day itself, twenty five thousand people rallied against the poll tax, of whom around three thy five hundred people marched off to Brixton Prison, where many poll tax prisoners were being held.

They were met by three thousand police in riot gear and they clearly wanted revenge for the march riot.

They piled in attacking the crowd.

Speaker 3At a certain point the police just waded in with batons.

I got trunson on their heads.

I had to go to hospital and the whole demonstration was broken up.

Speaker 1This was despite the fact that Dave was clearly marked as a protest steward wearing a pink fluorescent hives vest.

Other demonstrators tried to defend themselves and by the end of the day and unknown number were injured.

One hundred and thirty five were arrested and forty police were injured.

But this time, unlike in March, the police weren't able to control the narrative of what happened, which was reported in the media.

Because of preparation undertaken by the organizers, including putting together a video crew, which Dave discusses in detail in our bonus episode for our Patreon supporters, campaigners were able to show that the police were the aggressors who launched a premeditated attack on a peaceful march.

Speaker 3That was really the last attempt, I think by the government and the police and the media to really.

Speaker 5Undermine the movement.

Speaker 3So it was announced that, you know, at one point that winter, fourteen million people weren't paying out of you know, something like fifty percent of the adults in the country weren't paying.

The Conservative Party began to implode on the issue in early ninety ninety one, the Conservative Party lost some super safe seats you know, with massive majorities, were being overturned and they were losing to the Labor Party and the Liberal Democrats.

Speaker 5And the general.

Speaker 3Feeling was the poll tax, which had been portrayed as the flagship policy of the Conservative government at the end of the nineteen eighties, was actually becoming, you know, the millstone around its neck, and there was talk of challenging Margaret Thatcher to leadership battles inside the Tory Party.

Some people were saying it's all down to the poll tax.

We've got to get rid of the poll tax.

Speaker 1Opinion polls were showing Labor as being hugely ahead in national polls fifty five percent compared with twenty eight percent for the Tories, although this lead was hugely reduced if people were asked if Michael hessel Teime were Tory leader.

Hessel Time was a government minister who'd consistently opposed the poll tax.

Eventually, with pressure mounting on Thatcher, the Deputy Prime Minister Jeffrey Howe attacked her position on Europe and on her autocratic style, Sensing blood in the water, Other leading Tories joined in attacking her and the poll tax, and so the party was forced to hold a leadership election between Thatcher and hessel Tyne, with the poll tax being the primary issue at play.

Thatcher did come out ahead of hessel Tyne in the first ballot, but she didn't win an outright majority, which dealt a death blow to her leadership.

On the twentieth of November nineteen ninety she was forced to resign.

John Major was elected to replace her, and he appointed Hesseltyne to be in charge of the poll tax and to undertake a review of the policy.

But importantly, he was not authorized to abolish it, so the campaign against it continued.

In a desperate attempt to save the tax, the Conservatives tried to lessen the blow to taxpayers by offering rebates to half of all payers, which was a move which was mocked by the newspaper of Business to Financial Times, pointing out that even Major admitted that quote there must be something wrong with a tax which starts with the principle that everyone should pay and ends with a system under which eighteen million out of thirty six million people have to be offered rebates end quote.

Then they announced that they would reduce the poll tax for everyone by one hundred and forty pounds per person, with the difference to be covered by an increase in sales tax vaight of two point five percentage points.

But this wasn't enough for opponents of the poll tax, who continued to insist it be abolished completely.

In early March nineteen ninety one, the Tories suffered another devastating by election loss, losing their fourth safest seat in the country to the Liberal Democrats.

With the poll tax clearly shown as the overriding issue at stake, organizers planned another mass protest to coincide with the anniversary the Trafalgar Square riot.

Speaker 3So we planned an anniversary demonstration.

The Trafergo Square Defendance Campaign and the All Britain Anti pol TAC Federation.

Speaker 5Planned an anniversary demonstration.

Speaker 3It was March the twenty third, nineteen ninety one, because don't forget, councilors were meeting to set the following year's rate all over the country.

You know, it was the same thing again in the build up to the next financial year.

There were protests all locally, so we said, of course there must be a national demonstration through central London, not a rally as in October and this was extremely tense.

We bought Trafalgar Square the Travgo Square defendant's campaign, but this time the police conceded that the march should go to Hyde Park.

I was involved with the meetings with the various least senior police officers involved with the demonstration, and it was extremely tense.

Nobody wanted to be blamed if the whole thing degenerated into a battle, and as it got closer and closer to the dates, it became a big political issue in the media and in Parliament.

Speaker 1In the end, though the demonstration proved to be unnecessary.

Speaker 3Two days before the anniversary demonstration, John Major announced the poll tax was going to be scrapped.

Speaker 5He said, it's unenforceable.

It's going to be scrapped.

Speaker 1Michael Heselteiin stated that the poll tax would be replaced in nineteen ninety three by a council tax, a banded tax based on property value, more similar to the old rates system.

But of course they did still intend to keep the poll tax for a further two years.

Speaker 3Following that, you know, the poll tax administration kind of carried on, but you know, the stuff it had been knocked out of the whole administrative drive to enforce it.

Councils couldn't cope anyway.

The registration kind of system was in chaos, and eventually what was announced was that if bills weren't well.

It wasn't so much announced but we announced it was that there's a statute of limitations.

If the bill is not collected within six years, it has to be written off.

So we were just calling everyone to hold firm, don't pay, and millions and millions of people never paid a penny.

Speaker 1In loading in Scotland alone.

In nineteen ninety four, while the new council tax had mostly been paid, there were still nearly one hundred and twenty four million pounds in arrears from poll tax non payers, and the Finance Officer for the Authority complaint of a hard core of people who still weren't paying.

By the time the six years was up, councils in England and Wales had to write off and estimated five billion pounds in unpaid bills from four million people.

In Scotland, the debt didn't expire in six years, so the non payment campaign technically continued up until twenty fifteen.

Then the Scottish Parliament passed a law writing off the last remaining debt from the tax of around four hundred and twenty five million pounds, in a move which was still condemned by the Conservatives.

Speaker 3I think they eventually, you know, a couple of years after that victory demonstration, they had to bring in a little alternative tax called the council tax, which was based on households and homes rather than individuals.

Speaker 5So it was a big success.

Speaker 3I'm not saying that the council tax wasn't oppressive, you know, but it wasn't as bad as the poll tax.

Speaker 1Now this touches on something which unfortunately people comment regularly on our social media posts about the fight against the poll tax.

A typical comment says something like, then the poll tax was just replaced by the council tax, which was exactly the same.

But this is just completely wrong.

As we discussed earlier in Part one, the poll tax was a charge on every individual in a household.

So a household of two parents and two children over eighteen living in a small flat would pay four times as much as a billionaire living in a mansion.

So in Haringay, for example, this hypothetical family would have to pay two two hundred and eighty eight pounds a year, worth over six thousand pounds in real terms today, compared with only five hundred and seventy two pounds for the billionaire.

The previous system domestic rates was based on household paying a single rate based on the rental value of their home, so a billionaire in a mansion would pay much higher rates than our example household of four.

The current system of council tax is more similar to the old system.

It's based on households paying a single rate, but this time based on the sale value of their home.

So again, our billionaire would pay higher rates than our family of four in Harngay.

That was oney three hundred and sixty three pounds a year when it was first introduced, with a family in an average flat paying four hundred and eighty four to six hundred and sixty five pounds.

The council tax is still a regressive tax because it's not proportional to people's ability to pay.

However, it is a lot less bad than the poll tax, so claiming they're the same is not only wrong, but it does a real disservice to one of the most important working class movements in British history and all of the millions of people who participated with the poll tax defeated.

Dave and other grassroots activists tried to strategize about how they could keep momentum going to take on other issues in their communities.

Speaker 3So as the anti Poultex campaigning began to wane the necessity for it, we and Haringey were saying, well, you know, how can we build on this, How can we learn from what we've achieved, And we encouraged anti poll tax groups to transfer into general solidarity organizations, supporting a wide range of campaigns, supporting industrial disputes, supporting you know, clayments and struggles and whatever in local areas, because that's really what's needed.

It's ongoing solidarity and mutual aid and support for protests before making society better.

That's what we did in Harringay.

All the groups transformed into solidarity groups and then eventually coalist into one Harringay Solidarity Group, which still exists today.

So we've carried on having monthly meetings since nineteen ninety two and we've supported wide range of different movements, not ess campaigns, but also initiatives independent cinema.

We do a newsletter which we distribute for free to the public, and we've initiated various different housing action groups and so on.

So I don't know if the same thing happened inywhere else in the UK, but certainly it's something essential that every area needs, every area in the world needs that people there's a network of support for challenging those in power and supporting each other and trying to make society better.

So I think that's the lesson in real life that we learned from that movement.

But the lesson, I think the wider lesson is that people power is unstoppable.

If it has enough kind of public involvement in public supports.

Speaker 2They luck out.

Speaker 5They luck out.

Speaker 1That brings us to the end of this double episode, but we've got a great bonus episode where Dave talks more about some of the different left strategies within the campaign, how protesters organized the October nineteen ninety demo to monitor the police and push back against their lies, and about the activities of the Haringey Solidarity Group.

This is available for our supporters on Patreon and make our work possible.

It does take a lot of time and money making these podcasts and running the rest of the Working Class History Project, researching stories and reaching an audience of between fifteen and twenty five million a month.

So if you do appreciate our work, please do sign up to support us and listen to that bonus content now.

Just go to patreon dot com slash working Class History link in the show notes.

If you don't have the money right now, absolutely no problem, but please help us get the word out about this podcast.

Tell your friends and colleagues about here, and take a second to give us a five star review on your favorite podcast app like Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

As always, we've got more information sources and eventually a transcript on the web page for this episode link in the show notes.

One of the main sources we've used for these episodes is the excellent book Poll Tax Rebellion by Danny Burns.

You can get hold of it on the link in the show notes.

Thanks to our patron supporters for making this podcast possible special thanks to Jazz Hands, Fernando Lopezo, Haeda, Nick Williams and Old Norman.

Our theme tune is Bella Choo.

Thanks for permission to use it from Disky Dead Soiler.

You can buy it or stream it on the links in the show notes.

This episode was edited by Ingin Haasan.

Thanks for listening and catch you next time.

Speaker 2Manto belli, mondo bellida