Episode Transcript

As we come marchin marchin in the Beauty of the Day, A million darkened kitchens, one thousand mil last graye are breden by the beauty is Sun, Sun discloses, and the people Heresy and Bredden, Roses, Bredden and Roses.

Speaker 2Hi, everyone, and welcome to another episode in our Radical Read series, where we talk about historical and political texts that we think are important for workers and organizers to read, discuss, and inform our activity.

Just a reminder that our podcast is brought to you our Patreon supporters.

Our supporters fund our work and in return get exclusive early access to podcast episodes without ads, bonus episodes, free and discounted merchandise, and other content.

Supporters also get access to two exclusive podcast series, Radical Reads, as well as fireside chats.

Join us and find out more at patreon dot com slash Working Class History.

Usually this series is actually available exclusively for our supporters on Patreon, but in this case we're releasing this entire episode for free for everyone.

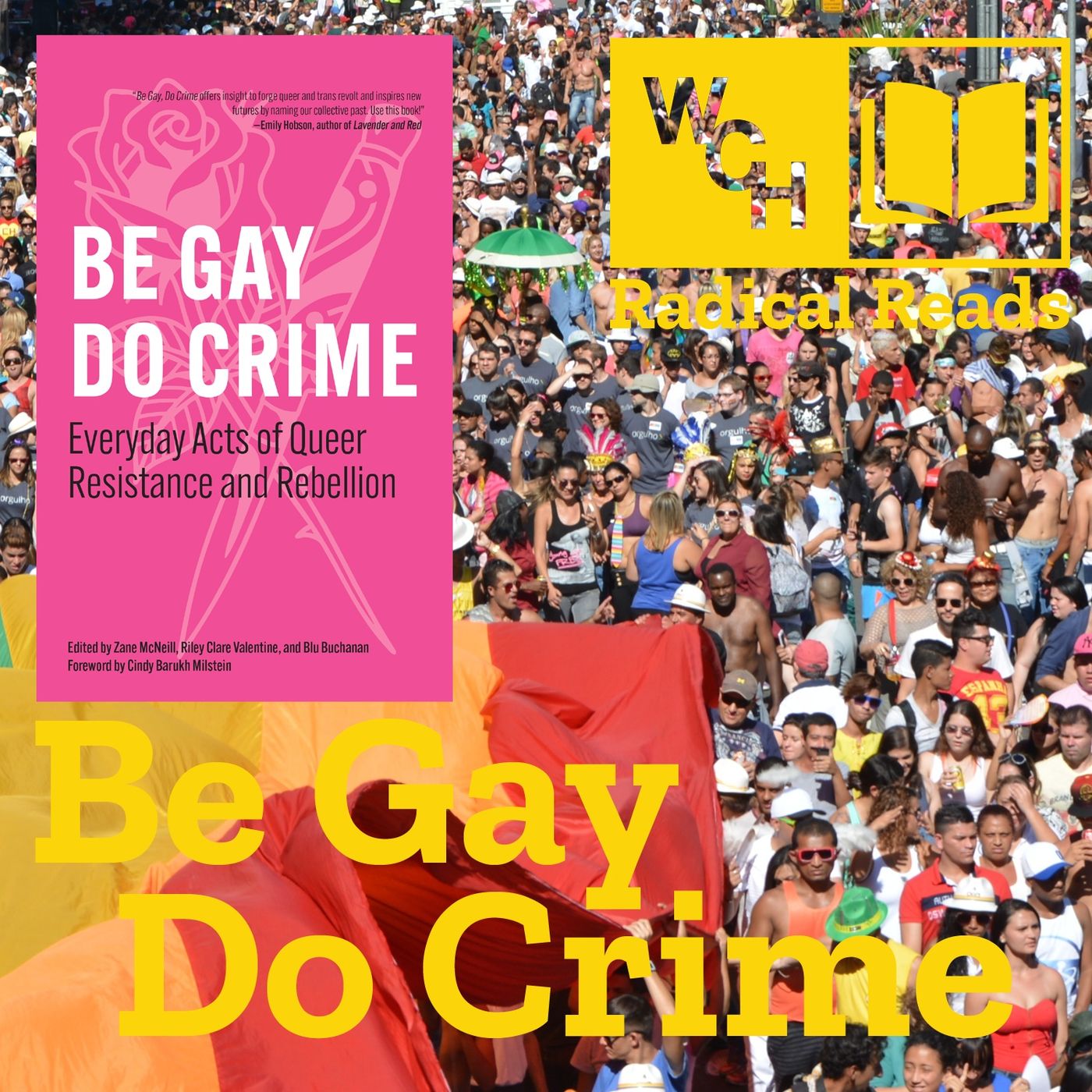

Today's book is Bgay Do Crime, Everyday Acts of Queer Resistance and Rebellion, edited by Zaine McNeil, Riley, Clare Valentine and Blue Buchanan.

It's the second book in our Everyday Acts series published by US Working Class History alongside our friends at pmpress.

The books full of hundreds of stories of LGBTQ people's history for every day of the year, and so giving the widespread assault against queer and trans riotes going on around the world, we wanted to get together with Zain, Riley and Blue to discuss the book learn more about queer history and its relevance to our current moment.

The book is out now available with global shipping in our online store, so do make sure you get hold of a copy today at shop dot work Classhistory dot com link in the show notes you can also get ten percent off using the discount code wh Podcast.

Before we get into the discussion, I just wanted to take a moment to explain some of the terms and concepts that come up in the episode.

So, for instance, pink washing refers to the use of gay and trans rites as a smokescreen for various nefarious practices, for example, the current genocide in Gaza.

Compat is short for compulsory heterosexuality and refers to heterosexuality being generally assumed as the default and contemporary patriarchal societies.

P COSE or PCOS stands for polycystic ovary syndrome, a common hormonal disorder in people with ovaries, which has symptoms including things like the growth of facial hair.

Speaker 3Roe v.

Speaker 2Wade was the US Supreme Court legal case which resulted in the establishment of a constitutional right to abortion, which has since been reversed with the Dobbs decision of twenty twenty two.

Anyway, with that out the way, I hope you enjoy the episode.

Speaker 4It's really cool to meet you all.

Thanks for doing this and for like doing the book.

You know, I really love it.

Excited to have it soon to be going out into the world.

Would you be able to kind of go around and introduce yourselves in a bit about your personal activist work backgrounds.

How have you want to do it?

Speaker 5My name is Nay McNeil.

You see him and they've done pronouns.

I have really specialized in Queer Appalacha.

I'm from West Virginia and also have done different advocacy work around anti carcial work and being an advocacy and animal rights.

I've just graduated law school and I am super excited.

I'm currently working on a book around ANERCR coomitism right now as well.

Speaker 6Hi, y'all, my name is Blue Buchanan.

I'm an assistant professor at unc Asheville.

So speaking of Appalachia, I'm over here in the web eastern part of North Carolina in the Blue Ridge Mountains, originally from the Midwest.

I sort of came to this project through two main ways.

One because of my research sort of what I look at, the kinds of historical work that sort of rejuvenate me.

And the other part is really through direct action stuff.

I've been taking part in labor trans black organizing, primarily in the Midwest and West Coast since about twenty twelve, so I'm sort of coming at this from both a scholarly and organizing perspective.

Speaker 3So I guess that leaves me Riley Valentine, Hey Thom, I'm from the Deep South.

I'm from Georgia and my family's all from Louisiana, and I grew up in a household that was very dedicated to Catholic social teaching.

So I remember, you know, talking with my parents about anti war activism and how it fit into theology.

We did a lot of work around poverty, immigration, and my mama did a lot of work in pushing for abortion rates, and she was born in the nineteen fifties, so this was like in the sixties and seventies in Louisiana, and I guess I became really involved in direct action more so during occupy when during Occupy Atlanta, I was on a group of organizers who helped start like I revived the Atlanta medic Collective, which was really which was really exciting.

And as life has gone, it's also kind of dovetailed with my academic interests, which are largely focused in care ethics and how we can rethink and reorient society from a more neoliberal focus to something that's more based upon like we toy careful one of them.

Speaker 4All Right, well, thanks for the introductions all.

Really nice to meet you, because up until now it's just been the odd email going back and forth.

And yeah, it's very different to meet people in person.

But could you maybe tell us, like how did you come to collaborate on be Gay Do Crime?

Speaker 3So there's a network actually of like trans academics at all like help each other and collaborate and I know, like through like my PhD journey, like it was invaluable having other trans academics to talk with, and that's how I got to know both Zain and Blue.

Speaker 6Yeah, just to dovetail off of that, it's because I know Zaan.

Zain was the one who reached out, was like, hey, there's this opportunity.

And in part it's because Zain and I had already worked around topics around activist history.

So we had worked together on stuff for the Activist History Review and so Yeah, Zain had reached out was like, you know about some additional communities this project, Really we want to be as intersectional as possible, and so they asked if I could participate and really bring some of the again stuff around black history, some of the postcolonial stuff that I had learned about in grad school into the project.

So really Zain was out here organizing the people.

Speaker 5Yeah, and I had worked with pm Press previously on a collection around Queer Appalacha Callediolomys All the Emerging Voices Queering Appalachia.

And I'd worked with Steven from Pmpress and he had reached out to me right before I started law school actually like three years ago now, and I was like, hey, we want to work on this project.

We want to do a kind of collection where we're able to put all of these really rich and diverse moments and queer history together.

And even though the project itself has been through multiple iterations and really shifted, that kind of rooted in movement is something that I wanted to bring to this And because I knew Blues work, like Blue said, and A knew Riley's work later on, it is really, like I've said before, like a monolithic project, I think, broader and richer and more than any of one of us could have done.

And so all of us as well as other queer entrance people in the community, helped us to try to make this collection as authentic reflection of where we come from as possible.

Speaker 4Yeah, because I wasn't really sure how it came about, because I think that Stephen at PM Press and we I'm not even sure who mentioned it first to the other, but we both kind of had the same idea that following our kind of first book, Working Class History, every day Act of Resistance and Rebellion wanting because that was a broad book about a little bit of everything, and we couldn't do justice to any of these kind of particular different types of intersecting struggles in kind of single volumes, and I guess they had the same thought that it would be great to produce more volumes, you know, even with any other topics like quite history or black history or anything like that.

On their own, one book can't do anything but provide the tiniest snapshots.

But I think the book does a great job of providing these snapshots, and then people can look in the references and learn more sort of from there.

And so in terms of the book, how is it kind of put together and how do you hope that readers are going to use it and relate to it.

Speaker 6Well, The way that we structured the book was chronologically, right.

We start off with our readers on January first and only basically work our way through the calendar year.

And we thought about this with a lot of intention, because the goal was to make the book a part of people's everyday lives, right, a sort of everyday meditation and everyday activity where folks could gather with friends, family to think about how sort of radical queer history impacts them and what lessons they can take into the present moment.

I know that one of the things I imagine we'll talk about is our current political environment.

The idea was structuring this in a way that made it easy to feed folks, feed their spirits and get them to really engage in taking what they learned about history and making it their own.

Speaker 5I think for me, something that was really important for me is especially when I started, both of my siblings were in like middle school and elementary school, and both of them were also queer, just a different kind of flavor of queer than I was.

And I always want to be the person in their life that I wish I had that was able to give them the space to grow into who they were, to experiment, and to feel safe in doing so.

And I think this is the book that I wish I had had in middle school and high school, and I throughout college too, and now to be able to know that not only am I not alone, but I come from a long lineage, a global lineage of resistance and community and joy that made me feel safe, and I want to make sure that they also have that experience.

Speaker 3So I'm actually I'm a high school teacher and I get a lot of kids come into my classroom to talk about a lot of thoughts and feelings, and I teach history.

And so for me, like I have you know, kind of alternative like alternative history books in my classroom so that students who are curious can pick them up.

And a lot of students have asked about having you know, LGBTQ pluss history, where's queer history?

And in my curriculum.

We tried to make it as intersectional as possible, but there's not a lot necessarily there that's written in a way that's really accessible, especially for young people.

So this book is something that I'm excited about because I could see my students being really excited to read it.

And I think that's really meaningful because a lot of our history books are written for you know, academic audiences and are in textbooks, so there's not as much as accessible for younger people.

Speaker 4Yeah, and I you know, I think that is how a lot of people are going to use it.

I know we've heard from our first book quite a few people that used it, and I'm sure we'll do the same with this one.

Are people like parents of young kids to kind of go over at the breakfast table or the dinner table, and teachers and things like that.

And I think dates and anniversaries are funny because they're so arbitrary and they don't kind of mean that much.

But like a lot of people, when you relate to things that happened in the past, it seems kind of very distant, and perhaps a link with the present isn't always that obvious, but just something being the same date as today, if something happened on it's the eleventh of July.

Today, just something that happened on the eleventh of July, it does kind of pull it into them and it's like, oh, today, isn't you know something just like that could be today or whatever.

But if it's an everyday book going by the year, I mean just having a look at the very first day, I mean, and from the title of the book as well, Be Gay Do Crime, you can immediately see that state repression is a feature here because well, I mean, the title is it's fun and its provocative, but I guess also it's not even so much about being going queer just has been a crime and indeed is criminal in so many ways.

And from the first of January it's very clear, with multiple stories about police and state repression of queer people.

And you've got examples in the book going back literally hundreds of years.

Could you maybe say a bit about how LGBTQ plus people have been criminalized sort of historically, and how does this criminalization also relate to other concepts like class and race and disability and things like that.

Speaker 3Well, particularly when it comes to disability, because I do a lot of work in disability.

I have epilepsy, chronic pain, and various things, so a lot of my work is in disability studies.

And the crossover between the control of bodies that we see with disability also is there with queerness.

And typically you see people who their bodies are being surveiled are always have other intersectional identities.

It's very rarely people who are wealthy, who are white, who are fully able bodied, who are the ones who are being examined and are being persecuted.

And oftentimes these histories dovetail with histories of colonialism, with the theories of racism, and with the stories of disability enableism.

So all of these things coal is together so that it's impossible to examine queer history, kind of as you said, with working class history without looking at other histories and other systems of oppression and structures.

Speaker 5Riley and I are working on a book right now, that's really on this idea of how laws will change.

But the idea is to control bodies and control relationships and sexualities, whether that looks like surveillance in different ways or the actual incarceration of certain kinds of bodies, and how these laws might change.

But whether it's you know, the gender affirming care bands that we see right now or the different kinds of dress laws from fifty sixty seventy years ago, the idea is over surveilling populations, controlling the way people gather and love and fuck, you know, in different spaces, and then really making it so that they're able to coercively either incarcerate or control or create this idea of what family values are for the state.

And I think we see that a lot through this collection of moments right that these are people whose identities are being criminalized, like you said, whose way of engaging in community, of just having a body of performing gender is criminalized.

And so what does that mean when existing is a criminal behavior but also a way to create spaces of joy and community and resistance and liberation.

And I think something really difficult, it's mean we really wanted to do in this book is show not only the harm that happens from these systems, but also how people chose to exist, how they wanted to exist and able to thrive and love despite that.

Speaker 6Yeah, so often queer in trans life is only recorded or only talked about in those moments of like death and violence.

Right, people are only remembered when they are sort of recipients of harm.

Part of what we wanted to do with this book was to both note that harm and that people are living through alongside what's happening.

June Jordan has a great collection of essays called Some of Us Did Not Die, and it's sort of in a similar vein in which we're trying to emphasize that, yes, we aren't unmarked by these histories of violence, but we're also not contained by and only limited to those experiences.

I think to answer sort of the broader question about queer and trans people being criminalized historically, it's important to recognize that queer and trans folks really experience a new moment within society with the emergence of the nation state.

Right.

There's lots of different formations of statehood before then, but the idea of the nation state is relatively new, and it really put queer and trans people in a new position to be criminalized, right, or in a new position to be visible, right, because the nation state has always been interested in creating populations of people, people who are biologically a particular way, who need to be controlled and managed or excised, right.

And so when we think about it that way, we get into the fact that homosexuality is really coined in the mid eighteen hundreds, and so this concern about populations becomes really important.

And this connects deeply to class, race and disability, right, because the nation state is increasingly interested in trying to figure out how to homogenize its populations to better control them, and in order to do that, it has to identify people.

And so the fact that queer and trans people have been part of this identification process and also resisted that identification is important.

So yeah, class race disabilities, certainly, I think we also need to connect the fact that queer and trans people, when we're thinking about who's vulnerable are sort of multiply compounded along the lines of class, race, and disability.

And I also just want to point out, in addition to sort of thinking about disability from some of these other lenses, really talking about how disability can be created by structures of violence, right, that sort of social model of disability.

Thinking about the fact that, for instance, if you have an anxiety disorder, as I do as a black person in the United States, that makes sense.

There is a lot of reasons to be anxious, right, And so realizing that not only is it that our struggles are interconnected, but that the forms of control and violence that produce quote unquote different populations are also interconnected.

Speaker 1Right.

Speaker 6The things that create disability also create these other categories.

The last thing, just as an example that I wanted to share, right in Germany, you had the creation of sort of heterosexuality and homosexuality, and this led folks like Magnus Hirschfeld to say, look, we need to decriminalize both sexuality and gender identity.

The danger that came along with this was in participating in that nation state project of creating populations, because folks like the Nazis turned around and said, well, if we can't re educate them out of this, and if they're just a part of the biological population, then we need to get rid of them from that population.

Speaker 5Right.

Speaker 6So, again, just speaking to our current moment to where we're at It is also important to recognize that we have strategies to address the violence that comes with visibility.

Speaker 4For listeners wanting to know more.

There's more about the specifics about Hirschfeld and the Institute of Sex Research and what happened with the Nazism in the book.

So it's also very timely given them many aspects of the current situation.

And yeah, I mean just an anecdote about the aspects of criminalization and class referring to some of the things you mentioned about kind of stories about bad things happening.

Is also a bit of a problem with historical records because often when you're looking back, especially looking for specific dates, you know, like this project, there are dates for when people were executed or for when people are arrested and things like that.

Whereas you know, so many, especially because of the criminalization of queer life for so long, many these moments of joy they weren't written down, they weren't recorded because they were you know, illegal.

But you know, it's a testament to the work you've done that you know that the sense of community and joy really comes through.

In the book.

You highlight a lot of kind of I guess you could call it like political acts of resistance or you know, quite deliberately political, like specific demonstrations or things like that.

But could you maybe say a bit how some of the less obviously political acts of resistance, like forming communities and survival strategies, how that's played a role in queer resistance through time.

Speaker 6Yeah.

So there's actually a really great quote by a black trans artist called Juliana Huxtable who had been asked by an interviewer, what's the nastiest shade that you've ever thrown?

And she responds by saying existing in this world?

Speaker 5Right?

Speaker 6And So I say that in part because I also want to give a shout out and recognition to folks who didn't survive.

Speaker 2Right.

Speaker 6Some of the framework that even the book sort of wrestles with is talking about surviving as an act of resistance.

But in some ways that can also sort of negatively shade, right, those folks who haven't managed to survive the various forms of violence that they've experienced.

So I just also want to give a shout out that it is about the living that is the act of resistance rather than the survival.

And I think that's part of what Huxtable is pointing out is that it is the act of existing, It is the act of relationship that is the political act itself.

And I think that that drives a lot with my own perspectives as a black trans organizer.

And I think, as you had pointed out, it's difficult to put that in a book with dates because it's something that is every day but community formation and survival.

I mean, I think that's as deeply political as you can get.

Right.

The moments that we try to highlight are just that there are moments that highlight a lot of work that has happened way before that moment.

And I think that this is especially highlighted when we see folks like Miss Major, who's a black transfigure who talks a lot about the care work that is required in spaces, pushing back against the disposability that is often imposed on queer and trans folks to say that you don't have to like everyone.

The point of doing the political work is not that we are best use.

It is to recognize that when we change our conditions for the better, when we make sure that we all have our basic needs met, it becomes possible to do something new or to do something otherwise.

And I think that a lot of the insights of these black trans organizers come not just from the experiences of violence, but from leaning on one another.

So yeah, I would say that survival is what makes those more overt acts of political resistance possible.

Speaker 4That's a really great answer.

Something that we sayh have focused on in terms of our research is the role played by the Empire in propagating homophobic values and laws around the world.

In most countries today where homosexuality is illegal, were part of the British Empire, and in most of those places it's British colonial era laws still on the books.

You've mentioned already about the creation of the nation state and the need to create and manage populations.

So in terms of that project, you know, what do you think is about queerness that you think authorities government states finds so threatening in terms of creating these manageable populations.

Speaker 3I would say, don't forget the Labor Party has just signed on to throwing trains people under the bus, much like the Democrats in the United States.

Words of a flother do flock together.

Martha Nusbahan has this amazing tact.

She writes about how discussed, particularly when it comes to queer people revolves around the idea that we exist in aminality.

And so when you take that within the nation state and in more of a political science perspective, just like Blue is saying, if your body can change genders or exist between genders, if your family doesn't necessarily have to follow the way a heteronormative family looks like it's necessarily have to involve children, thinking of Lee Edelman here, like the death drive right, So queer people in a lot of ways challenge the ability of the nation state to exist and to function, and so our existence is in a lot of ways, like the quote you know that Blue gave right, existence is a huge way of just addressing and refuting the ability of the nation state to control bodies, to control identities, and queerness is I like to think of it as like a positive force of destruction.

Speaker 4And I suppose this is something which affects the you know, states which call themselves socialist or communists as much as kind of capitalist ones, because once they find themselves in the position of actually managing an economy, especially if we look a bit further in the past through the twentieth century, the kind of economic cornerstone of capitalist society including in countries that didn't call themselves capitalist with the nuclear family and the reliance on unpaid labor of women workers in the home and in terms of childcare, and so I suppose so even that's obviously the case in places like the UK and US, but even in places like the Soviet Union, where whereas like Carl Marx wrote about the need to abolish the family, the government that called itself Marxist was like, no, the family is the center of everything, and you've got to get rid of abortion and ban homosexuality and you know, create this little new clear family where the woman does the work of reproducing the labor power of the male worker and also the future generations in the home.

I suppose that's why in recent years there's been an attempt to I guess you could call it co opt LGBTQ people into the status quo, allowing gay marriage and even encouraging it, and you know, spreading that idea of the core nuclear family.

Speaker 5I wanted to just say that one of the most surprising parts of this project was how queer labor history is for me, especially when we think of FDR in the US.

Right, Really, the success of the labor in his government was because of Eleanor's lesbian community who she brought into be part of the Department of Labor.

And so a lot of the success of what we think of the Golden Age of labor comes from queer lesbian feminists and so that I think has really changed the way I think through labor organizing, both in the community micro labor work as well as in federal organizing in the US, because a lot of that came from her friends, which is something that I didn't know before I started this project.

Speaker 6Yeah, I just wanted to add alongside that a few things.

One is just to give a shout out.

A book recommendation in addition to ours, is called Transgender Marxism and Transgender Marxism Fabulous right also talks about how trans folks are situated within exactly that kind of like material reproduction process, and I definitely think that part of what queerness does is it challenges the basic bio essentialism that rests at the heart of the Name State project as well.

So just wanting to sort of draw that out.

I sort of also want to point out for folks who may not be as familiar with some of the controversies within the community, the difference between talking about queer community as like Riley was pointing out, and like LGBT as like a sexual or gender community, and really trying to differentiate between the two of those, particularly because I look at right wing gay men, I see folks who identify themselves as part of a minority sexual community, but that sees the state and its violences as something that they have to participate in in order to get recognition or protection.

And I think that whether we're talking about those right wing identity groups or whatever state government authorities system those systems are inimical to queerness because at their root, part of what queerness does is say you don't need to take the terms of that sort of Faustian deal right, you don't have to participate in nationalism, patriarchy, domination in order to live fulfilled and again relational lives.

So, just as Riley was pointing out that you can have a family and it doesn't have to look exactly the way that the nation state wants that family to look, I think that what causes concern for the nation state is that queerness disrupts important structures of socialization, the kind of socialization that makes violence natural or normal or just a biological requirement.

We have so much social Darwinism into the nation state as well, and queerness says we don't have to fuck with all of that in order to be human, right in all of the complex and messy ways that being human manifests.

Speaker 4Yeah, I think that's a really interesting point.

Going back to the book and the very first page of it, we've spoken about the themes of state repression, but another thing which is immediate on the first page is the connection between queer liberation and other types of liberation, specifically black liberation.

I wonder if this is something that you were kind of deliberately trying to communicate or is this something that just emerged naturally through the history and what happened.

Speaker 5I think it's both.

I think that there obviously is a really rich history of black queer and trends organized at the same time really sort of historically tense between black organizers who are queer in like a Black Panther Party and other things in this rights movement who also ended up being sort of marginalized in that space, and so very like messy but really rich history there.

And so I think partially it's because we wanted so much of the Archive.

You know, we've been talking about the Archive.

I always have a huge issue with the Archive because so much of our history is race, and those stories that are told are either these really heinous stories written by the state or really reflect the wealthiest, whitest property owning histories, right, And I think that's what Worker History in People's history really tries to challenge about what this idea of history really even is and who is profiting off of the way our histories are told as truth.

And so we really wanted to challenge a lot of the Archive that really reflects that those kind of marginalizations and erasures while uplifting other parts of queer history.

At the same time, we're limited.

So even though we tried really hard to bring in these stories as some way, it was still difficult because of the limited archive we are working with to really do as much justice as I think we wanted to.

Speaker 6Yeah, just to go back to something that you had pointed out earlier, sort of about Britain's involvement in sort of global homophobia and transphobia for that matter, I think just going along with what Zain said, there there were two sort of separate aspects.

One was a subject position question, right, So part of this volume emerged from our own subject positions.

We sit at a number of different intersections, and so we were bringing our own knowledge of our own communities, histories and events that we wanted to see, right And certainly again as a black trans person, that was important for me to share out.

And I do think that that lends the book a through line that is focused around sort of black liberation efforts, because that is an important intersection for myself.

So part of that is there.

I think that we also can see that the construction of what it means to be all of these categories is about who is entitled and who isn't right, who's entitled to the freedom of private property, who's entitled to the freedom to express themselves in particular ways?

And while that has caused some problems, it also means that, for instance, black people, as c Riley Snorton says, right, that maybe being black is a trans experience, right, and vice versa.

So I think that part of what also emerges from this in some ways is a breakdown of those categories, right to say that, actually, if you want to know about black history, you're gonna have to know about queer and trans history, right and vice versa.

So I think that part of it is that because we are trying to read against the grain with these archives, that means that we're going to come up with stories that are centering folks who are multiply marginalized, I will say, and Zaan pointed it out as well, though, that we ran into a lot of limitations.

So we were familiar with certain archives, right.

I have been to archives in Germany, the UK, Canada, and the US, but like that is by no means the breadth of the archives around queer and trance history that exist around the world.

And despite purchasing as many books on queer history from as many people as possible, I mean, there's also language barriers right.

Speaker 5There.

Speaker 6I was struggling to learn German so that I could read some of the primary materials, right, So there absolutely are difficulties when trying to engage with I mean counter history right in many ways.

One of the ways that I think Riley, Zaane and I sort of dealt with that ambiguity or that tension was to say, this is an invitation, right, like this is a starting place.

It's a it is a starting place, show knowing how we took our intersections and turn that into a series of stories.

But it isn't an end.

Speaker 3Yeah.

I think Blue's comment, especially about language is really important can't be understated as well, because also like whose stories get written down, like the practice of a story innography.

You know, there's languages that die out every single year, and a lot of them are indigenous languages, and so then we end up lacking those histories.

So, like Blue said, this is an invitation and hopefully we're going to see more intersectional queer history.

Speaker 4Yeah, definitely, And you know that is an appeal to listeners and readers of the book as well, to make more history and write it down somewhere in the book.

It doesn't look like a coincidence that quite a lot of the stories are from the nineteen sixties and nineteen seventies.

We did podcast recently about a wave of workers' strikes in the US during the Vietnam War, and kind of that wave of worker militancy basically in the US emerged as a direct result of the civil rights movement and struggles against colonialism, for example in Vietnam.

You know that kind of fed into this just general atmosphere of workers rebellion.

Would you think that the same is also true for the queer liberation movement around the same era.

Speaker 3I would say absolutely.

And within this moment, you know, you have mainstream organizations like the Gay Liberation Front, but you also have breakoff organizations like the co He River Collected right, made up of black queer women who were Marxists, who are like, we don't feel represented in the mainstream Black civil rights movement.

We also not feel connected to the women's rights movement.

So you see queer people well really taking advantage of this massive energy happening and creating these movements that have long lasting legacies.

Speaker 5And I had brought this up a little bit before, but like you mentioned, a lot of these movements were training grounds right where queer folks also face marginalization.

Right the Black civil rights movement, a lot of queer black activists face similar marginalization from their comrades in that space and then moved into other spaces.

The same thing with vin m war activists.

A lot of the people learn the tools and tactics from these movements and then use those later because they felt alienated.

A lot of the same thing and the communist movement there are a lot of queer activists and the communist movement who then faced a lot of homophobia and were sort of forced out, but use those tactics to fight for other movements, fight for themselves, and so like for me personally, I come from a sort of orientation and consistent anti oppression where if you're fighting for queer liberation, you also have to fight for every other kind of liberation because the state, right, like Blue had mentioned, uses the same tactics and tools to control all of us, And so you can't really fight for one liberation without the liberation of another or group of people, or the environment or animals.

And I think that because of we usually sit at a multiplicity of marginalizations right that are sometimes forced onto us.

Right you were talking about class.

Some people won't understand why queer and trans people have a lot of issues with housing, right with access to food, why so many of us are living in poverty, right that are pressured or move into sex work that therefore leads to criminalization and realvize right.

But a lot of that is a state putting onto us these not having access to other kinds of different kinds of work or capital, our property right so and then, like we mentioned disabling, and so a lot of us sit in a space where we're finding for a lot of different groups, and we have a lot of identities that we want to fight for.

And so after being trained in these movement work and then being alienated disillusioned, a lot of those tools, I think we're used for the queer liberation movement.

Speaker 6Yeah, just to build off of that and maybe be a sociology nerd for like just a second.

But like in social movements research, they talk about isomorphism, which is basically that coming up with strategies that work for a social movement, right, that like effectively manage to maybe persuade your audience or win concessions.

That takes work, right, And oftentimes it's easier to look to see what has worked for other people and adapt that to your own particular issue or concern, right.

And so there is a lot of social movement isomorphism, a lot of transfer between different social movements because when you find tactics that work, you make use of them.

I also just wanted to pick up on something that Zaane talked about, which is like we are all often connected to multiple movements, right, but we can't do everything.

So like, maybe I'm out here being like I'm going to focus on trans housing.

That's gonna be my thing, and sure, absolutely these other problems equally important.

But I can't do everything or be everywhere.

But I do know the trans girl down the way who is working on a different issue we talk, right, And that's also where maybe a strategy or tactic that we learned about in our organizing space can be adapted by somebody who is working on the same issue, but just from a different sort of entry way.

So again, almost like a dandelion model, right, we don't have to be everywhere and do everything, but when we strengthen our relationships with others across those lines, we transfer forms of knowledge and organizing in faster and more flexible ways.

Speaker 4So while a majority of the stories that you feature in the book are about the Western world, they are a good number from the global South and from countries which have been formally colonized.

What sort of like similarities and differences did you notice in terms of the repression and the resistance of queer people in those different places.

Speaker 5I feel like, again that's something we're really conscious of within our limitations, is there is this sort of majority narrative discourse where oh, the quote unquote global West is so great with queer people.

Of course they'd be a little less so now, but that was like the main narrative, right, and then like, oh, the global South, this is a horriblace for queer people.

And again we've talked a little bit about what empire means with that, right.

But at the same time, we really were conscious of this idea that, even though it's sort of sorts snippets into different kinds of history, that we might accidentally reify this discourse if we just sort of reflected you know, Canada and the US and the UK.

And even though I think we did that a little bit, because like Riley and Blue set our limitations and our archive and then language, were really really wanted to focus on broadening what queer history looks like, and in the moments I think we brought in, I would say a lot of it that I've noticed were similarly trying to get some kind of legal recognition, whether that looks like being safe, or being able to change your name or access gender firming care, or if there is some kind of harm, having the state try to rectify that harm instead of criminalize you.

And so I think a lot of the same struggles are ones we see that were previously done in the US and being able to just have you know, like your your gender marker or your name or be safe.

Right, It's like what people need ends up being very similar, and the tactics I think are similar, right, whether that looks like trying to go to the parliament or lobby different officials, or march right or create community spaces.

Like a lot of the same tactics that we saw in the US are things that we also saw in other countries.

Speaker 6Yeah, just to add to that, well, maybe it bears mentioning that like the US and Canada are also part of the colonized world, right.

I know that certainly.

It is difficult when we're talking about like the global South versus the global North, and that there are for example, say, there's a lot of discourse happening among black Americans right now about are we American?

But when we're talking about sort of colonized folks, particularly indigenous and black folks in say the United States, we are also colonized, right.

And I say that because I do think that again, at least something that I've tried to bring forward in consistently in our discussions is the impact of the black radical tradition on thinking through some of these questions, not just taking colonization seriously as something that happens out there, but something that is sort of part and parcel of that nation state building process, part of empire.

As Zay had mentioned before, and I would say that when we're looking at the differences and similarities across these contexts in terms of proximity to the benefits of colonization or proximity to repression and violence caused by colonization, what I noticed in terms of responses is less that it's a whole different toolkit, but in many ways that the tools are being adapted for the particular set of harms.

Right, we can see harm reduction strategies.

Folks who are like, yeah, we know that, say, looking for this legal representation is buying into all that British colonial nonsense.

But we also need access to our healthcare.

Right, So if the differences are really about answering the particular structures of violence, the similarities is as Zay was pointing out, that fundamentally these are about meeting basic human needs, and if we're not getting them through some places, How do we get them through others?

Speaker 4Right?

Speaker 6Some of what we're seeing is differences in the public visibility of those resources.

Is it more of a whisper network right in which folks are sharing resources or is there more public visibility or institutional investment and so Yeah, I would say that the biggest difference is in like where folks are at in terms of their visibility, And I would say the biggest similarity is that across the board, what folks are organizing for is the meeting of their basic human needs.

Speaker 2We'll be right back after these messages.

If you want to listen to our podcast with our ads, join us on Patreon, where you can also listen to all our other Radical Reads episodes, as well as our other Patreon only series fireside Chats.

Support from our listeners on Patreon is the only way we're able to devote the time and money it takes to make this podcast, So learn more and join us at patreon dot com slash working Class history link in the show.

Speaker 4Notes, How did you work together?

How did you find that process?

And deciding on what stories you were going to include?

Speaker 3Isn't that Internet a beautiful thing?

Speaker 7I believe we had at one point three Excel sheets with like changing entries as a way to also keep track, because it was helpful for us to make sure we could go through we had like a short summer to be like, okay, what's this about.

That way it helped not get too redundant as well, and to make sure that we could, oh, like this is a huge gap geographically or this community we haven't necessarily talked about, So that was really helpful for tracking.

I've never used Excel sheets more in my entire life, but I found it to be a really easy way because we're all incredibly busy, you know, Blue and Eye.

Speaker 3We teach, and we're researching Zane doing law school.

Like having like consistent meetings is that's almost impossible with all of our schedules, so we were I think we were able to coordinate really well, especially given how busy we were.

Speaker 5I was gonna say this project, since I mentioned, has gone through so many re iterations and has shifted a lot and expanded and brought in a lot of ways.

I think it was very queer and the way we went and a very messy in that too.

Like I had my backgrounds mostly working on ended collections, and I wanted to facilitate as many voices as possible, but then that didn't work in this kind of collection because it got way too big and it was I wanted to bring in more voices and more experiences, but at the same time we had to limit it.

I wanted to bring in different scholars and activists who could look over and review what we were doing, and I did some calls at different scholars, like, hey, did you look at this?

How are you to this book?

Like Blue said, And We've I read probably like fifty different queer history books and was able to talk to or email a lot of those different scholars and would share, you know, the s Excel sheet with them, like where are the gaps?

Where are the problems?

Speaker 7Right?

Speaker 5And then those reiterations would change what the project look like.

And like, I think we've really gone over as we were all very conscious about what we didn't want to reify to cause harm.

We had challenges around whether we were bringing in someone who was harmful in one way but still important to queer history and another way.

You know, I think all three of us a lot of our work is challenging assimilationist LGBT rights movement, but at the same time, one legal history is much easier to find than a lot of other kind of history, and some of those if you need something for every date, you know, is just having a certain law in place?

Is that problematic?

Is there other things we could bring in?

Is it's still the work that people put in for that, you know, really important to queer history, even though it's not what we consider protest work.

And so the book itself has just so much labor in it from the three of us, like a wild amount of work has been put into it, from the editors, from PM Press, from working class history, and all of that is very conscious conversations going into every single moment about why is it important?

How does it reflect working class or people's history, or what is protests or what is queer right?

How could someone who wouldn't identify as queer because, like Blue said, gay and lesbian and queer were more sexual activities, not identities until later on.

What does it look like if as three Americans we are focusing more on America, Canada and the UK, how do we really challenge this idea that queer history isn't white and rich at the same time, like that's what the archive reflects, and so the whole process was very queer itself, I think, and just us trying to navigate a very large project and at the same time stay true to the moments we wanted to have it reflect.

Speaker 6Yeah, this was my first like time doing a book editor position, so I was coming into it with fresh eyes.

I'm a first gen academics, so like, I do not have a sort of lineage to draw on when it comes to putting together something like this.

And as part of that, it was a learning process and sometimes a rocky one.

See those Excel sheets, Oh my gosh.

And also part of what both Zane and Riley sort of pointed out, which was, turns out, not every month is the time when queers are at their busiest, you know, doing revolting things.

So like June chock full, so many all of the entries, but like, turns out, like February is kind of a down month for the quick year in trance folks.

So like, it definitely became difficult when you're like, hey, I need to find something for February twenty eighth.

That's not really the way that our social memory works, right, And so that became became difficult.

There was also just uncertainty around dates.

One source says that it happened February sixteenth, and another source said that it happened two days later.

How to reconcile those dates?

What source do you privilege?

And I also think just to name you know, Zan was talking about this sort of queer experience, it was also a labor experience, right, I think for all of us thinking through division of labor, how do we make sure that things are equitable?

What does it mean to do equitable work from different subject positions?

Speaker 3Right?

Speaker 6All of that was a much bigger part of the process than I expected.

But one of the things that I appreciated was that it was out in the open, like those conversations were happening, and they weren't always comfortable, but they were being talked about, right, And so it was particularly coming from academia where so much of this stuff gets swept under the rug about differences in labor and work.

I appreciated that.

With the co editors, a lot of it was about being very upfront, being very clear about what our limitations were and where we were at with the project.

Speaker 4Yeah, that's really interesting and it does reflect some of the same kind of issues that we had doing the first WH Every Day act book, and especially with all of the spreadsheet and Google sheets, like wh kind of runs off if ever, like Google sheets goes down where screwed?

And yeah, with the dates as well, and February twenty ninth is a tricky one to fill as well, because we do like to kind of fill every twenty ninth as well, and thankfully we're able to with this one.

Yeah, in terms of there being busy months and not busy months, Yeah, this totally happened with the general history as well, and even some dates, Like we've got some individual dates with like twenty five stories and then some dates with like two.

I think sometimes you can kind of like be a bit flexible about Often stories include multiple dates, so maybe if you've got one a little bit missing, you can pick an aspect of the story for this date or what have you.

Yeah, But so, were any of the stories that you put in here ones that you were kind of personally involved because some of them are pretty recent.

So were any of them ones that you were kind of personally involved in?

Speaker 5I donot know if I was personally in any of them, but I certainly was tangentially connected and a lot of it.

A lot of those moments that I brought in were like ones for my high school right that, like other people who aren't from Morgantown, West Virginia wouldn't know, we have Firestorm in there in Asheville, a queer bookstore and collective that I've been going to since I was like fourteen or fifteen.

After at LOSCA, I worked at Truth Out as a breaking news writer, and so some of those stories are ones that I was able to write about when the news was breaking, and so like, I feel like, I'm not sure if I was particularly in any of the resistance movements that are are brought in, but I certainly was in community or touched them in some way.

Speaker 6So the June ninth, twenty nineteen was actually an event that I took part in.

The entry is for the Sacramento Pride shut down, So that was something that I was directly a part of.

It was an effort by black and brown particularly folks, to say that we can't have pride while participating in forms of violent oppression, and in particular, the issue was around the inclusion of police in pride.

So that was one that I was excited to get into the collection in part because again those smaller cities not to call Sacramento a small city, but like it's not the San Francisco's or Las of California.

Speaker 3Right.

Speaker 6It shows that like again, those working class folks, those folks of color that are in these other places are also doing this work, and sometimes they are in fact leading the way in doing that work.

Only to have those bigger places practice the same tools, tactics, techniques and get more visibility.

I'm not going to say I'm a little shady about it, but like just it's it felt very important to see that work amplify it.

Speaker 3Yeah, honestly, there's so much in there it's really difficult to remember.

But there were things like all my families from you know, Louisiana, like Lawtel, Small Bayou and getting to write about the Upstairs Lounge bar, I was really excited.

And there were some things that we had that like we were kind of talking about whether or not to include, like the anti Kkak protests in Atlanta, which I was a medic of, and there was like this joyous Hire Radio dance party during it that was really amazing.

That was all largely organized by black queer organizers and I can't remember we included that or not, but there were moments like that where we were going through I was like, oh, yeah, I think I've been there.

But there are so many entries.

I can't remember how long the book ended up being.

It's like over three hundred pages.

It was so many things.

Speaker 4Yeah, you know, so it is good value for money as a as a plot, you know, stories for your buck.

You are getting a lot.

I mean, maybe you could ask this question of each of you kind of individually.

Were there any that you put in that like particularly kind of resonate with you or particularly important to you on some level.

Speaker 6Yeah.

Two of the entries that I thought were really important to me personally.

The first is from June sixteenth, eighteen thirty six, was about marrying Jones, and particularly as a black trans person, seeing a story about Mary Jones, black American sex worker in the eighteen hundreds, one of the first trans folks ever recorded in an official capacity in the United States, was really important.

One we have images of her.

She is fabulous.

But also because again when we talk about these archives, especially archives that involved black folks, slavery did a lot to sort of erase the gender subjectivity of black folks, because, as so many scholars talk about, black folks were reduced to their flesh or reduced to their labor potential rather than having an internal subjectivity.

Seeing someone like Mary Jones, who is sort of owning and crafting her own subjectivity in the pre Civil War period was really important.

The other entry is from April twenty sixth, nineteen sixty eight.

Kiyoshi Coromea basically held a demonstration against the use of Nepal in Vietnam.

And what they did was they announced plans to burn a dog alive with napalm in front of the university library.

It got thousands of people to gather together in a protest, and instead of like engaging in this burning, they were leafloted saying congratulations on your anti napalm protest.

You save the life of a dog.

Now, what about the lives of tens of thousands of people in Vietnam?

Why does it feel so important as an entry to me?

So much of where we're at in this current moment, and particularly with the rise of fascism, has been the normalizing of violence and this idea that as long as we engage in acts of dehumanization, violence is fine and I think part of this has grown in my analysis with my connection with Zane, thinking about like those species boundaries, right, and thinking about that contentious relationship.

In particular, I think black folks have with some of the anti speciism language that's like, hey, yeah, we don't want to say that people are better than animals, but also we're often treated so much worse than animals, right, And so thinking about those instead of as like tensions that keep us apart, thinking about them as productive spaces to keep building forms of like CROSSBC solidarity.

So just something that's really sat with me pretty heavily from the entries that we collected.

Speaker 5For me, something that I really wanted to be able to include this book was activism that we could learn from and relatively recent activism, especially in other countries.

Because I lived in Budapest, Hungary for two years.

I went to Central European University for my masters, which is pushed out of the country by urban and the fit does government, and so I was there really at a point in time where like my queer friends were, you know, getting beat up that the secret police were knocking on your doors.

There weren't any gay clubs at the time, but if you're going into queer spaces.

They were like salons and sellers, right.

And I've always been very vocal that the US is always just like five years behind Hungary, maybe six or seven behind Turkey, and then you know, a handful more behind Russia.

And so a lot of the moments we included were things from the twenty tens and early twenty twenties from these countries, because these are activists that we can talk to.

You know, these are the same laws that are being ripple effect by international afar right actors that are being shipped to the US, shipped to the UK, shipped to Canada like in the US.

You know, Spack literally has been in Budapest.

You know, Victor Urban's talked to Jatie Vance and Trump.

Ronda Stantis was one of the first governors bringing in the Fidesque laws that were based on Russia's laws that we're now seeing go national and so recently, you know, the Fidez government in Hungary passed this law that was going to cancel pride survey everyone and use that as a way to increase the surveillance state and limit the rights to privacy that they were going to use this huge surveillance apparatus that anyone was going to march would be fined under.

And it was one of the biggest protests I think in the country, and the biggest Pride protest, and a lot of my tattoo artists, my friends were there, right, And so a lot of people, maybe for like the first time, have been really excited about Budapest and Hungary and activists there.

But I've been saying for years, like, let's talk to them, right, Let's talk to people in these countries where the governments are talking to each other.

Let's learn from these tactics that the queer activists are using.

Because I've lived in countries that are to my existence, and I know people who continue to live, but I still have had some of the most joyful moments of my life even in these hostile countries.

And I think that's what has led me to be very rooted and steadfast in this moment where the government, you know, has always sort of wanted us not to exist, but is increasingly more hostile.

Speaker 3Yeah, I love that.

Uh, for me A big thing was including moments where pride similar to what Blue is saying with their direct involvement, but other moments Pride has become a protest again.

We talked about prides where it became protests about the treatment of Palestinians, you know, and protests against pink washing, which now I think is more relevant than ever.

So are these intreues now about recent protests, recent things that have been going that people can trace to what's going now, and people can make those connections and hopefully find in spread and the fact that pride as a protest is something that's never ended.

There are always opportunities to take these moments where queer people are coming together and to channel that energy into a broader liberation and into refuting any sort of pink washing and any usage of our identities as a way to further or allow genocide, colonialism, or any form of violence and dehumanization.

Speaker 4Yeah, well, and all those concepts.

I think you did really get across with the selection of stories saying I think that thing you just mentioned I hadn't really sort of struck me before.

But I think certainly myself a decade ago, I wouldn't have thought, you know, if someone had said, oh, in ten years time, when we're thinking about what will be happening to people in the US or UK will be looking at places like Russia, Turkey and Hungary to see what sort of policies and change are going to be being introduced.

That's at least a good thing about looking back and doing history.

You don't have to make predictions for the future and then look like a ball.

But I would not have seen that.

But that is very much kind of where we are.

And so I think this kind of maybe transitions into the next step of questions, which is we are seeing this populist far right backlash and the new wave of repression against queer people in general, but trans people in particular.

What do you think of the primary reasons for this.

Speaker 3I think trans people similar to other minority groups in general.

I think it's an easy testing grown for further dehumanization.

Like if we can stop giving passports to trans people with the correction de marker, then who else's bodies can we start to regulate.

We see this in various other histories happening again, you know, I do a lot of disability.

Carrie Buck a white woman, She had a disability, and they the Supreme Court legalized sterilizations, which they used for Native people, they used for black people.

They continue to use that, and you know so, I think also because we're such a small minority, I think we're a testing growl.

And I think we've seen that in the United States as attacks against citizenships is, attacks against who can enter and who can leave are increasing, and you see that time and time again, particularly with the rise of authoritarianism.

Speaker 5One of my favorite Hungarian scholars is named Andrea Pato, and I was lucky enough to take a few of her courses, and I've gone to quote her and a lot of the pieces I've written, and she is like a woman gender sexuality scholar who was really focused.

Her academic work is really focused on how Italian women and Hungarian women really benefited from Nazism, actually, because I think usually in these frames there's this idea that women were oppressed, right, but at the same time of being a certain kind of oppressed, was also able to gain a lot of power, and a lot of her work currently because Hungary when I was there in like twenty seventeen twenty eighteen, was putting academics on lists right like they're doing now in the US, and she was on those lists, and a lot of her understanding of why Hungary if one of the first things it did was changed its constitution right packed its courts, changed the way the media works, continued the project of harming and exploiting roma populations, and then used this idea of gender and anti semitism really and anti mimigrants because this is around the same time that there was a lot of refugees coming through Hungary as ways to mobilize its population.

Right, like Riley was saying, queer and trans people are an easy testing ground as ways to then contain power over larger populations.

And what they saw a Hungary, So if they went out and closed the gender studies departments and changed it into like family studies, right when after queer scholars and women's studies scholars pushed universities out of the country and then at the same time did a lot of the laws that harmed the trans and queer populations and pushed them out as well.

And then overseeing now with these laws to expand the constitution, expand the surveillance state, using gender and trans and queerness as a way to use that to kind of close can veil the actual goal of fascism, right, and so queer entrance people in this system are used as a way to gain greater control, not over like over every single person, over every citizen, and really erase us from public life.

I will say that even though we see this as far right populism across the world, at least in the spaces I know, like the US and Hungary, it's very tactful, right.

It's a move towards autocracy and oligarchy, and by attacking the media and it slidifying control in like parliament, you know, putting different judges in places, you therefore control the information and control the people, and really control the vote because voting doesn't mean as much anymore.

So I have more faith in the people than our government structures.

Speaker 1Yeah.

Speaker 6Same, Uh So I do want to say maybe to start with that, I think naming that it is a spread of fascism is important because we've had a really hard time calling the spread of fascism over the past decade or so what it is, and I think that as a person who studies right wing social movements, it's important to name it so that we can do exactly what Riley and Zane have done, which is identify, Hey, these are the common tactics of this particular political culture, so that we can see the ways in which many of these things are not new.

And I think that that's especially important for obviously all of us as sort of historically minded thinkers, because you know, you pointed out that you know, you don't have to predict, right when you are a historian.

I'm a historical sociologist.

So my sort of training is in some way slightly different.

Speaker 3Right.

Speaker 6The goal is certainly to say, here are the past events, but it's also to say those things don't disappear right when tactics or strategies, as Zain was pointing out, when they work, they don't go away, right, And in particular, when we think about things like white supremacy, other forms of sort of fascist organizing, there are moments in time where they go into what social movement scholars call abeyance, meaning like they're not a hot commodity at the moment, right, Oh no, it looks bad to be called a racist.

But they don't go away, right.

They sort of get stored in our cultural memory.

They get stored in underground practices that folks engage in all those dog whistles, right, that continue to persist.

And so it does give us the ability in some ways to think about the future and to see, hey, you know what happens when certain conditions are met.

Just to play off of what Zain was talking about, and we discussed Magnus Hirschfeld before.

If we want to understand where trans folks are situated in our current moment, looking at the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany is a helpful comparison.

I think a lot of folks don't know that that really popular picture of the book burning that happened as part of a stormtrooper rally was actually the burning of books from the Institute of Sexual Research, which was Magnus Hirschfeld's work, which again was documenting all these various ways that folks experienced a variety of gender and sexual expression.

So to go along with what Riley was talking about with like we are small, a small group, and that enables folks to do violence, it is also about seeing how far knowledge can be shaped through violence.

And again this goes back to fascism's obsession with the idea of violence as the necessary sort of function of politics.

It also says might makes right right is such an essential part of this authoritarian and fascist organizing.

But to go back to an earlier part of what we discussed.

It goes back to this idea of bio essentialism.

If the foundations of fascism make the argument that the reason why government should be structured the way that it is is because there is a natural or quote biological reason for its foundations, trans people, queer people serve as an essential remind that it doesn't have to be that way.

That doesn't mean that queer people or that trans people or at least LGBT people as communities, can't participate in those forms of fascism, but rather that the underlying logic is still about saying that certain bodies should and have to act certain ways right, And a lot of this comes up with this idea of like women's rights versus trans rites.

Instead of dealing with the patriarchy, it's about reframing the question to say, don't look over here at these structures of violence, but instead take the scraps of what that system, the proximal benefits that Zayin was talking about with women and fascism, and make it so that the only way that you get those proximal benefits is by turning on folks who have less structural power.

And like, this is something that gram she talks about.

Right, He's sitting there in prison wondering why did like the communist revolution that happen?

How did Italy end up with fascists instead?

And a big part of this is about redirected attention, right and redirected focus.

Speaker 4Yeah, and I think there's also something with trans people being such a small minority.

These populist and far right parties, they often talk about economic concerns, from Trump talking about the cost of eggs and groceries to wanting to bring back manufacturing to the US and all that, which, of course is never going to happen these far right people.

If anything, all their policies will lead to lower wages, worsening conditions, and impoverishment of working people and poor people.

So they're never going to do anything to make any of that better.

But they can point to this very small group of people that a lot of people won't even know one individual, because you know, bigots often hold ideas about groups in their heads, but when they know members of that group, they kind of think, well, this member I know is different or whatever.

But you know, a lot of people won't even know a single trans person personally.

But you know, these far right, people can at least point to this group that they've harmed to be like, well, at least I've had done something, you know, like as you said with women's rights, that the Republicans in the US, who are very open about their hatred of women, you know, and have been for decades, can now say about how they're protecting women and girls by maybe they've banned one trans girl from a sport or something in a sport of fifty or sixty thousand people.

And you know, in the UK this is happening as well, with the support of a lot of the political left.

I mean, the Tory Party initially banned gender affirmation treatments for miners and labor.

Now they're in power have made that van permanent and under labor well.

A completely ridiculous Supreme Court ruling has basically established that a lot of protections which had been understood to be in law inequalities law to trans people actually don't apply.

And a bunch of this is being supported by people that call themselves feminists, socialists, communists and even some anarchists in the UK at least arguing that trans rights are coming at the expense of women's rights.

How would you respond to that argument.

Speaker 3I would respond that the improvement of life for one group always includes the betterment of life for all people, and that these fears and concerns that women have for safety, those are very real concerns.

You know, in the United States, domestic violence is not taken seriously.

You know, it's really hard to prosecute someone for rape, even when it's videotaped like we've seen.

You know.

I feel like when I was in college, there were time and time again of like violent campus rapes that just were not being prosecuted, and it was and it was horrible.

And those things are happening and they're not they haven't ended.

And the rollback of Roe v.

Wade and Dubs is forcing women, particularly impoverished women, women of color, women in the South, Native women.

They're limiting their rights, they're limiting their access, and so women are being harmed absolutely, But it's not by trans people, but by making trans people kind of like this phantom in in me, it allows people to have something to concretely channel their anger towards.

Even though our lives together only make one another safer and better, but it can feel so much more.

I think overwhelming to tackle a system of patriarchal violence when you've grown up and have seen all of those attempts to address those harms fail repeatedly, and so for sometimes this feeling of almost like a win is a win even though it's not, and it will in the end only serve to harm women.

We're seeing that women who are gender non conforming are being harassed when in states that have tried to pass bathroom bills, So these laws are actively hurting women.

And as Blue said, like the larger problem is, it's patriarchy.

It's not trans people, it's not us.

But tackling patriarchy is so much more daunting and requires it would require an overhaul of the entirety of the United States, not just the United States.

It's not like the UK, Canada.

All of those things would have to be addressed, Like I would say, a global politics would have to be prodressed in a way that most people, people empowered, do not want to do.

So if they can shift shift the target from themselves, then why not.

Speaker 4Yeah, I couldn't agree more.

And the fact that some people are buying it, I just find completely unfathomable.

How just completely I mean, how does completely stupid some people are especially like these groups that are funding these so called women's rights organizations in the UK fighting for single sex spaces in quotes, and they're all these US based evangelical anti abortion groups.

That's who's providing the money, you know.

And if you look at their addresses, their office space are being provided by these anti abortion groups.

Speaker 6Well anyway, Well, I was just wondering you were pointing out this idea of like even these folks who ostensibly have like a good analysis in other places, seem really drawn in right by this narrative around quote unquote protecting women.

And I just wanted to say, alongside what Riley had added before, this idea of protecting women quote unquote, how that can still be a sort of patriarchal call to action, because especially if we look for example, at the history of like anti black racism, right when we look at these other histories that are so intimately bound up the idea of in particular protecting white women has played an important role in legitimizing violence against other groups of people, while simultaneously laying the work to say that those other groups, particularly racialized groups, don't have women, that those folks aren't women in the first place.

So I think one of the reasons that even folks who ostensibly right like have this well developed political analysis, are willing to buy into it is because protecting women, as Biley said, doesn't require addressing the patriarchal reasons why women quote unquote need protecting.

Instead, it says, yeah, you can feel like a strong man, you can feel like all of those things that a good Republican wants to feel, by basically advancing an argument that as long as you're keeping other people that aren't you say, as a powerful person, right, as long as only you can harm women, then it's okay, right, you're protecting women from the ability of others to harm them.

And so, in part I say this because black trans feminism, one of the basic parts of this is recognizing that black women, even if they were defined as cis, had a very tenuous connection to the state of womanhood itself, right, And that doesn't mean that some black women still haven't like, participated in this right wing politic by doubling down and saying, well, the reason why were women is because of all these biological reasons.

But part of what black feminism tells us is that the state of womanhood is also a state of exception, and it's a state of exception that can be rescinded for all kinds of reasons, including being trans.

But I think Riley you pointed out that like all you have to be is like look outside of a norm in order to suddenly be kicked out of bathrooms, right, what about folks who have like pecos right, oh my gosh, a little chin hair, Suddenly like you're kicked out.

Like, part of what this does is it's trying to stake out a claim about womanhood.

But the only function of womanhood that it's protecting is the function of womanhood that is deemed valuable not to women but to men right and to patriarchy more generally.

And I just wanted to say, like, this is also meant that we have Republicans, for instance, calling for like genital checks on you, right, like things that But I feel like many of those anarchists or those leftists would say that's wild, right, like that, like we that would absolutely be an infringement on anything a feminist would claim is important.

But the moment that it's framed as protection, folks seem willing to overlook the fact that what it does is it puts one's gender expression within the realm of property rights and the state right saying that the state has a vested interest to protect you, it needs to have a say over altering shaping defining who deserves to have protection and who doesn't.

Speaker 4And I think you're referencing of both the kind of racial connotations of protecting women dating back to the lynchings of of black men.

Point is very valid.

And also I don't think it's a coincidence that so many of the controversies recently about quote women's sports have been around questioning the womanhood of black women athletes.

And I think that, yeah, what I was trying to say earlier, you've kind of explained my kind of blown my mind at how these people can can buy into, as you say, thinking that some people like Fox News commentators, as if they genuinely care about women's sports, as if we haven't heard the jokes that right wingers have made about women's sports for the past fifteen twenty years, that you know, they've been very clear that they do not care.