·S1 E377

378: When Bad Companies Buy Good Carbon Removal

Episode Transcript

Hey, thanks for listening.

This is Ross Kenyon.

I'm the host of Reversing Climate Change, the podcast you are listening to right at this very moment.

Before we get into the bulk of today's show, I'd love to tell you about our sponsors, Absolute Climate and Philip Lee LLP.

I've made great radio with both of them.

They should be familiar to you if you listen to this show, but I want to tell you about why you should learn a little bit more.

The first sponsor is Absolute Climate.

I did a show with their founder Peter Miner few months back and a lot of people love that show.

I was asking a question of can registries design their own methodologies for carbon markets without it being a conflict of interest?

An absolute climate's thesis is no, they shouldn't be in the business of doing that.

We actually need to disintegrate functionality within carbon markets even further.

They are literally the only independent standards body for carbon removal that exists.

Their name is very well chosen.

I think they are some of the most aggressively idealistic people within carbon removal.

It's come up on reversing climate change so many times about how and why there's tension between commercial teams and science teams within carbon markets.

There's some fundamental tension between the rules of running a business, or I should say the rules of running a profitable business is maybe a better way to put that and climate impact.

And I think Absolute is one of those companies that, at least from my experience of what I know of them over there, I think they're going to be some of the staunchest holdouts just trying to make sure that there can be a justified true belief that a ton purchase is a ton truly removed.

They're betting big on not compromising.

It's a bold strategy.

I respect the absolute hell out of that.

Absolute is very much doing things their own way, and they stand out to me and I will never mistake them in a lineup.

Go check them out.

I really am endlessly fascinated by what they're doing.

And that's also true of our other sponsor, Philip Lee LLP.

In fact, I told him to pitch me on some weirder legal shows.

I really like doing shows about the law.

I think the law is such a fascinating part of our shared social life.

It structures so much of it.

It's badly understood by most people.

Just structuring deals within carbon removal is hard.

I'm talking grown up deals here, like when you're trying to put together an enormous package, complicated structuring, a lot of money, changing hands, The stakes are high.

You really do need a good lawyer.

I'm sorry to tell you that if you are a startup out there in carbon removal, you're going to probably pay a fair amount of money to lawyers.

There's just no way around it.

Your choice is basically do you get a bad lawyer or a good lawyer.

One really cool thing I can say on Philip Lee LL PS behalf.

Well, one Ryan Covington and I did a very fun show about how basically no one except for an elite few really know what bankability and project finance even mean.

And he lays it out very clearly.

If you'd like to go listen to that show, it's awesome and it's LinkedIn the show notes.

And also we end up talking about Ernest Hemingway for him not to.

So it keeps with the tradition of reversing climate change.

One also really cool thing is that they just won Environmental Finances VCM Law Firm of the Year.

They put it three years in a row, 2023-2024 and 2025.

It's the only award for legal teams operating in the VCM, and they have offices in the US, Europe and the UK.

You should check out Philip Lee LLP.

Thank you from the bottom of my heart for listening to this and thank you to our sponsors.

You really make this so that it's something that in a busy life with lots of competing priorities, I'm able to keep coming back and making more.

Reversing Climate Change, thanks so much for what you do.

And now here is the show.

so much for listening to Reversing Climate Change.

I'm Ross Kenyon, I'm the host of the show and a carbon removal and climate tech entrepreneur.

I can't sugarcoat it.

I have a doozy of a show today.

This is not an easy show to make.

I'm going to attempt to treat the topic with a great degree of care because it is not a straightforward question.

Some of the best shows of reversing climate change, in my personal opinion, are ones where I'm able to contrast a couple different points of view that I think have a part of the puzzle.

I'll tell you more in just a second.

In the meantime, if you could open up your podcast app right now, give the show 5 stars on Spotify on Apple Podcast.

Please do the same.

Write a quick review on Apple Podcast and say how much you love the show.

It helps so much more than you know.

It would be so appreciated by me if you could please do that.

There's also an option for $5 a month to become a paid subscriber.

It gets rid of all the ads that I don't read myself.

And you get bonus content, special episodes, extended conversations that didn't make it into the main show.

You'll get those and no one else will the link to become a paid subscribers in the show notes if you'd like to.

There's an expression that I think explains the tension within carbon markets very well.

In fact, I often come back to it, and if you know me personally, you've probably heard me say it.

The line describes the Catholic Church, and it says the church is not a club for Saints, but a hospital for sinners.

The goal of carbon markets is not to get together with all the companies that are already doing more than most and to pat ourselves on the back and talk about how great we all are.

That's not the work you need to be out there with the sinners, with the companies that really do need to decarbonize, really do need to be funding carbon removal.

And that means working with companies that aren't necessarily the most environmentally friendly, maybe even those who are recalcitrant.

Those are the ones who need it.

The line itself, I always thought it was Pope Francis, and it turns out it's not.

And in fact, the original quote is something like the church is a hospital for sinners, not a museum for Saints.

I like Club for Saints because that makes it feel like something that we believe ourselves to be a part of rather than a museum where we're looking at it.

So I'll actually like my little what I think was maybe my twist.

I don't know, I associated this with Pope Francis.

Maybe it's not.

It seems like someone else who originally said this, and this is very clearly a riff from the Gospels of it is not the health that you need a doctor, but the sick that the job is to go and sit with the Pharisees and tax collectors.

And those are the people that need the attention, not the people already in the flock.

I like this line.

When I say this line, people connect with it.

People understand what it means, it's clever, it's wise, and I think it's true.

If you can bring a company into climate action, even if it is nowhere close to what is truly necessary, that action on the margin was additional.

Good job.

That's an impressive thing, and I'm always happy to see stuff like that.

But there are also companies that participate in carbon markets and maybe even carbon removal.

They don't feel as good for me.

What would you do if there was a company that you felt like the world might be better off if they didn't exist at all and you knew they were in the market for carbon removal?

They either have an RFP out where they've already bought some carbon removal and you're looking at this RFP and thinking, well, I sure would like to have a prestigious customer like this.

What can I do to get this deal?

You might privately find this company to be distasteful, to put it lightly, and yet commerce pushes you together.

Sometimes people who have a free market orientation see this is one of the benefits of capitalism.

People like Deirdre McCloskey are famous for talking about the bourgeois virtues.

There's actually an essay I really like by Bart Wilson, who's an experimental economist, and he wrote about the difference in The Wire between Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell.

Avon Barksdale represents the aristocratic way of interacting with the world, and Stringer represents the bourgeois way of dealing with the world.

So Avon and Stringer are both part of the same drug dealing gang in Baltimore.

Avon came from the streets, is someone who is comfortable with violence, cares about honor, and is willing to defend the corners that his gang fought and died for.

Even though Stringer suggesting that it may be better off to trade some of those corners for peace, for greater access to their product.

And that with everyone agreeing and having a contract with one another, they could all be wealthier, safer, better off than they were previously.

Avon does not like this because it goes against the old school aristocratic, honor based way of understanding oneself and one's relation to others in a power based system.

And Stringer is commercially minded, he's bourgeois, he doesn't care about honor so much as does this work, is this safe?

Are we making money?

Can this persist?

And I've always really liked that way of understanding that tension in the Wire and between bourgeois and aristocratic values.

It's a great illustration of it.

And so if we take that lesson to carbon removal in carbon markets, we might say that these bourgeois values allow people who may not even like each other that much to work together.

So if, for instance, you do not like a major purchaser of carbon removal, but you work at a project developer and you need to sell to them, Commerce has effectively goaded you into baited you into those all sound pejorative.

It helped you give up your previous distaste to find a system of mutual advantage that was better off than the alternative, at least on some metrics.

But I think there's some part of your heart that might have some aristocratic leanings in it, because it also just feels weird to put pecuniary interests above something like honor.

That's a a virtue that's potentially higher than mere commerce.

And I'm trying to make sense of how I actually feel about this because it is really complicated.

I ended up thinking about the very famous political essay The Power of the Powerless by Vaclav Havel.

This essay may in fact be what he's most famous for.

He's a playwright and an author, and he is president of Czechoslovakia after independence from the Soviet Union.

And then when I converted into Czech Republic, he was president then.

And this essay is very, very famous.

And in fact, it's so good and so worth reading that I'm going to have to read several excerpts to explain why this is necessary and may help us unpack whether or not carbon removal is a club for Saints or a hospital for sinners.

Because he talks about what it's like being in the Soviet system and he he deemed that to be a post totalitarian system where in the old days of dictatorship it required quite a lot of overt coercion.

And Havel's writing after the thaw.

So Stalin's dead in 53, Khrushchev gives his famous 1956 speech where he denounces Stalin in 1956.

And so Basil Pavel is coming of age in a post Stalinist Soviet Union.

So there's a period called the Khrushchev Thaw, and there's a period where it swings back the other direction after Khrushchev is replaced.

Leonid Brezhnev came afterwards.

And there's also sort of a swing back towards Stalinist policies.

And OK, it's more than you need to know here, but so Basil Havel is coming of age in a time when we're past things like the great purges of the whole lot of more cat in the gulags are active.

But actually a lot of people came back from the gulag during this time.

But yet the system of the things that we all have to say to make nice in the world persist.

Within any society, there are things that just cannot be said.

There are things that we must say in order to make the nice, to make our lives go along and be easy.

It's true under communism, It's true under capitalism, it would have been true in Hobbiton.

It would like it will likely be true 1000 years in the future.

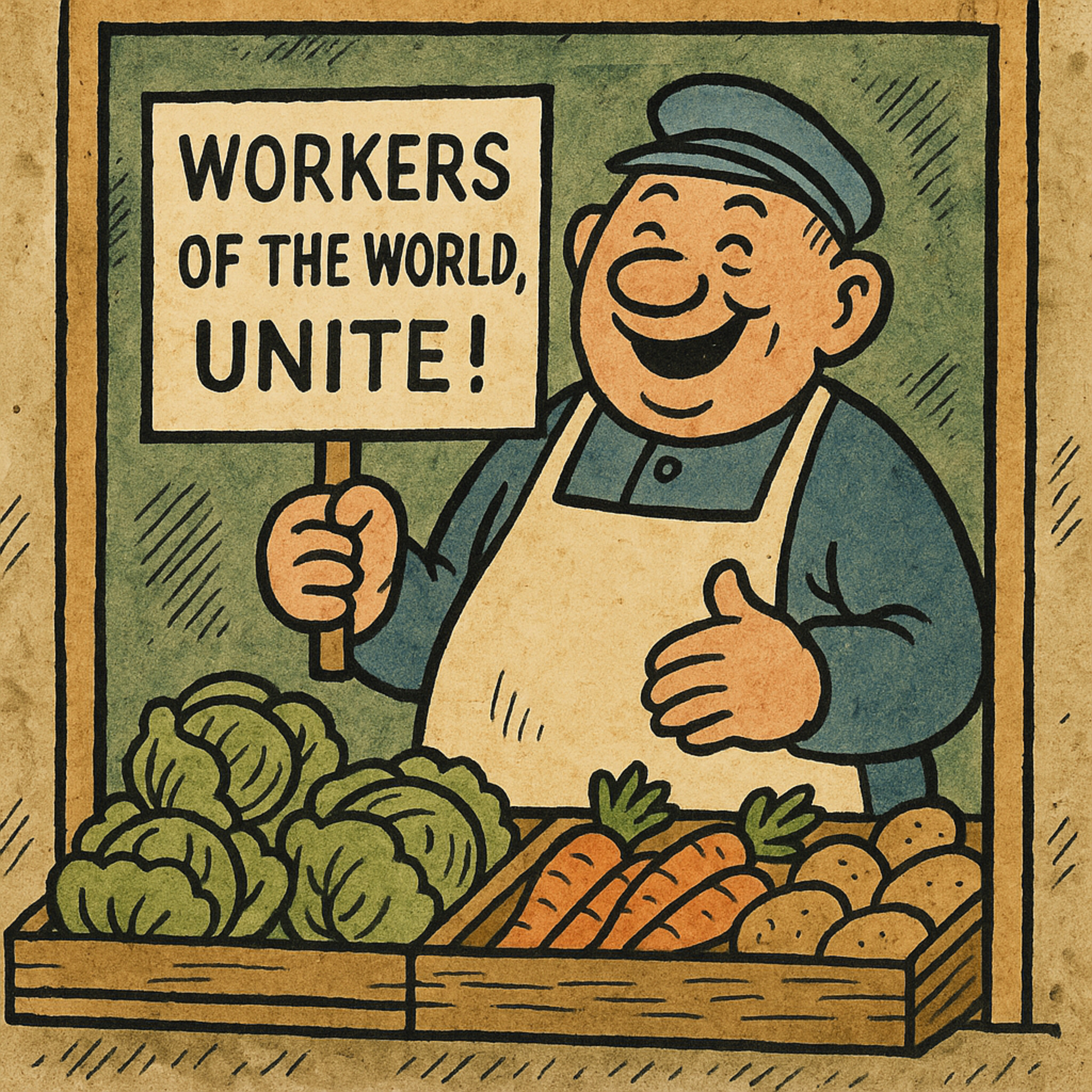

Wassup Hobble has this idea in mind when he weaves this story of a greengrocer.

The anecdote, the thought experiment, whatever it is, is good enough.

I'm just going to read it because I don't think I can improve upon it at all.

The manager of a fruit and vegetable shop places in his window among the onions and carrots.

The slogan Workers of the world unite.

Why does he do it?

What is he trying to communicate to the world?

Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world?

Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals?

Has he really given more than a moment's thought to how such a unification might occur and what it would mean?

I think it can safely be assumed that the overwhelming majority of shopkeepers never think about the slogans they put in their windows, nor do they use them to express their real opinions.

That poster was delivered to our greengrocer from the Enterprise headquarters, along with the onions and carrots.

He put them all into the window simply because it has been done that way for years, because everyone does it, and because that is the way it has to be.

If he were to refuse, there could be trouble.

He could be reproached for not having the proper decoration in his window.

Someone might even accuse him of disloyalty.

He does it because these things must be done if one is to get along in life.

It is one of the thousands of details that guarantee him a relatively tranquil life in harmony with society, as they say.

Obviously, the greengrocer is indifferent to the semantic content of the slogan on exhibit.

He does not put the slogan in his window from any personal desire to acquaint the public with the ideal it expresses.

This, of course, does not mean that his action has no motive or significance at all, or that the slogan communicates nothing to anyone.

The slogan is really a sign, and as such it contains A subliminal but very definite message.

Verbally it might be expressed this way.

I, the greengrocer XY, live here and I know what I must do.

I behave in the manner expected of me.

I can be depended upon and am beyond reproach.

I am obedient and therefore I have the right to be left in peace.

This message, of course, has an addressee.

It is directed above to the greengrocer superior, and at the same time it is a shield that protects the greengrocer from potential informers.

The slogan's real meaning, therefore, is rooted firmly in the greengrocer's existence.

It reflects his vital interests.

But what are those vital interests?

Let us take note.

If the greengrocer had been instructed to display the slogan I am afraid, and therefore unquestioningly obedient, he would not be nearly as indifferent to its semantics, even though the statement would reflect the truth.

The greengrocer would be embarrassed and ashamed to put such an unequivocal statement of his own degradation in the shop window, and quite naturally so, for he is a human being and thus has a sense of his own dignity.

To overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on his textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction.

It must allow the greengrocer to say what's wrong with the workers of the world uniting.

Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power.

It hides them behind the facade of something high, and that's something is ideology.

That's a lot to read, maybe more than I've ever read in a single block quote.

But I think it's such a profound statement here.

I can imagine this happening.

I don't have a discrete moment of this in mind, but I have seen certain purchases within carbon markets where some company will cut a deal with a big company that is not necessarily a responsible global citizen is someone that in the sober light of day, when we are not trying to receive commercial benefit from this company, we would all agree is not doing things the way that it should be done.

That we're not proud of the way that they conduct themselves in business.

And yet one has to make the nice.

I will see people who have concluded a deal talk about what great leadership this certain company or companies might be showing by their purchase of some carbon credits and how important their support and leadership is for this space.

There's a part of me that always feels humiliation by proxy in this when I see a company saying thanks of elevating them and their leadership to such an extent and is offering them some degree of moral sanction.

And I always wonder when I see this how sincere it is when people are allotting these not so nice companies, let's just call them bad companies in public.

Is this like hanging up the Workers of the World Unite sign when you don't really care about them uniting nor even really know what that would mean?

Are you just saying the thing to make business easier?

Do these companies actually need a stronger sense of moral disapprobation to steer them in the right direction, giving them approbation in this way?

Does this alleviate their desire or felt need to change because those who care about the environment have applauded their leadership in this way?

Does this result in additional climate action by encouraging them?

Or does this confuse matters by making us less serious and how we view things?

This came up a lot when Germany was closing down nuclear facilities and reopening coal facilities, or even recently with Bill Gates's essay, which independently of what he actually said, it doesn't really matter.

I'm talking about the discourse about it rather than the thing itself, because we live in the Society of the spectacle, and that's it's Beaudry Yard all the way down.

It's just we're living in the discourse.

The discourse of the Bill Gates piece to conservatives was that Bill Gates said in public that climate change is not really that big of a deal.

Or when the nuclear facilities get shut down in Germany and Cole opens up, conservatives look at that and think, like, was climate change a really super big, existentially catastrophic event that we need to deal with?

Or is it something that we can make weird decisions about and close down clean energy nuclear facilities in favor of coal because apparently it's not that big of a deal.

It just like looks like, is this a big deal or is it not?

And I wonder if that same dynamic happens here too, where if there is a company that we're considering to be a bad company buying good carbon removal or good carbon credits and one is blessing them with what is often a rather small inadequate amount of carbon credits being purchased.

Does that show that we aren't that serious about climate change that we consider it to be something that can be addressed in and he's really minor, frankly inadequate ways?

I think the answer to that could potentially be yes.

And if the answer is yes.

That doesn't feel very good to those of us who work on the side of different types of carbon credits, carbon removals, trying to make climate action work and trying to get voluntary carbon market activity going.

Because then we're we're in a position of cloaking bad behavior that if we didn't need the support of these organizations that we thought are not super ethical, wonderful organizations, we would never consider endorsing in this way or praising them for their inadequate climate action.

But because we are in a commercial relationship or seek to be in a commercial relationship with these entities, we essentially have to.

And how does that feel?

I'm going to go back to the Vasov Havel right now.

He illustrates this so well.

And the parallels between these two situations, I think, are so apartment that I'm just going to let him carry it from here.

Let us now imagine that one day something in our greengrocer snaps and he stops putting up the slogans merely to ingratiate himself.

He stops voting in elections he knows are a farce.

He begins to say what he really thinks at political meetings.

He even finds a strength in himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support.

In this revolt, the greengrocer stepped out of living within the lie.

He rejects the ritual and breaks the rules of the game.

He discovers once more his suppressed identity and dignity.

He gives his freedom a concrete significance.

His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth.

The bill is not long in coming.

He will be relieved of his post as manager of the shop and transfer to the warehouse.

His pay will be reduced.

His hopes for a holiday in Bulgaria will evaporate.

His children's access to higher education will be threatened.

And on and on.

You should read the essay in its entirety.

It's totally worth it.

But that's how I feel about this too.

Even in publishing a podcast on this topic makes me wonder, am I harming my own career prospects by saying this by even speaking in a way that doesn't name any specific company?

Because it's really not about a specific company.

It's more general thought of integrity and how we should behave given that climate action is so important and time is seemingly not on our side right now.

And I don't want to live in a lie.

And there are sometimes when I might like to more strongly call out behavior of certain companies that I'll see.

But I get the sense that doing so might make it harder for me to work in carbon removal.

I think that's a that's weird.

I find that to be a real downside to the VCM orientation of carbon removal and carbon markets generally.

You have to make the nice you're trying to solicit customers and your customers don't want to be called out for being horrible actors on the global stage.

Having to do a song and dance that that makes everyone feel happy and smile for the cameras is something that's that's really difficult to live with.

And to, to speak honestly about this, I think puts one in a really difficult position.

I mean, one example of this that I've seen was the way that Will and Holly Alpine started the enabled emissions campaign against Microsoft, talking about to what degree AI tools at Microsoft may be used to enable increased fossil fuel production and whether or not that's in line with Microsoft's other values.

They had to give up really cushy jobs and put themselves at risk to even bring up a topic like this.

And even me pointing to these principal people doing things like this, it it gets to another point of this essay that I wasn't even prepared to to read about, which is that Basil Havel talks about how when someone decides not to live within the lie anymore and to say these things out loud, essentially everyone is put in a position to have to punish this person and to cast them out.

He talks about why Alexander Sultan eats in the novelist was forced out of Russia.

And it's because having anyone who's willing to engage on this level sort of puts everyone else's charade into question.

Like me making this podcast now I'm like, oh, am IA coward.

Like, why don't I just like, start naming companies where I've seen these things where, like, I don't really like that this company is engaged in VCM work.

And just just bringing up the Alpines makes me feel like a coward in comparison.

Doing a podcast about this in such a big, kind of funny way.

Wow.

That's how good of an essay the power of the powerless is.

Didn't even expect to be feeling that or talking about that as vulnerable of me to even bring it up.

But it's the truth.

There's one other angle here.

Maybe this lets everyone off the hook, but I think it puts everyone on the hook in a productive way.

I said recently that books often find me, and they probably find you at exactly the right time.

I recently read my first Bosley Grossman novel, Everything Flows.

I think it's just wonderful book.

It's short, posthumously published.

It's about the the people who lived through the time period after the Revolution itself, but into the time period where Lenin is dead, Stalin is in power.

We're talking about like the 20s through the 30s and some of the 40s.

But really most of this is in the 20s and 30s of the whole lot of more.

The great famine in Ukraine and the purges and the 30s and just how many people were sent to the gulag or killed, starved, tortured.

And what it was like for them either to be on the side that sent people to their fates and protected themselves.

The people who didn't speak out about it, even though they they may have been able to.

And what it was like for the survivors of such a violence and having their lives ripped away in this astonishing fashion.

And he has this imagined scene of a court case, litigating informers who informed against their fellow Soviet citizens and sent them to terrible fates, and the prosecutor trying to get them to admit that what they did was unacceptable or morally wrong in some way.

And the defense counsel and the defendants are able to successfully voiced away these moral accusations and just say things like in Stalin's day, you yourself, comrade prosecutor, would have been accused of underestimating the role of the state.

Do you not understand that the force fields generated by our state, it's heavy multi trillion ton mass.

the Super terror and super submissiveness that it evokes in a speck of human dust are such as to render meaningless any accusations directed against a weak, defenseless individual human being.

It's absurd to blame a particle of fluff for falling onto the earth.

That's true.

Like, there is this, this prisoner's dilemma, literal prisoner's dilemma here, of being in a position where you're able to defend yourself or your family by ratting on others, even those who don't deserve it, might put you in better standing with the authorities and protect you from that same terrible fate.

What I like about Bosley Grossman is that he's so careful in his judgement of others.

His life did not go exactly according to plan.

He is persecuted for being Jewish in the Soviet Union.

In fact, there was about to be an enormous pogrom against the Jews in the Soviet Union in 53, but Stalin died just in time to prevent it from happening.

Grossman had books that the names were changed against his will that were kept from being published.

Not exactly easy to be him.

And as time went on, he drew more and more parallels between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in ways that obviously the Soviets coming out of the Great Patriotic War against the Nazis did not appreciate at all.

And yet he's so careful and so merciful.

He'll say things like, but here, too, we must stop and think it is a terrible thing to condemn even a terrible man.

He'll ask questions like, who is guilty?

Who will be held responsible?

This question needs thought.

We must not answer too quickly.

And he'll describe so many people in his book, so many anecdotes that I imagine many of them are based in reality or stories that he's heard of people who ratted on their neighbors.

The system as a whole just encouraged us.

And how much can we blame people for participating in a system like this that opting out of faces enormous personal cost.

You will internalize the cost of that yourself.

The world may not change.

And that's a really scary thing to be exposed in such a way.

And that's an extreme example, but compare it to my plaintive screech just now that I I would like to have clients full time work, continue working in carbon removal and thus have to participate in a system that I might occasionally like to call foul on.

But I also don't want to be seen as difficult.

I also don't want to be seen as naive or that's just not how business gets done or that's a childish way to participate in climate action.

Everyone knows that you go in through the front door with a suit, not in the back door with a picket sign.

That's sort of like the dynamic of I Heart Huckabees.

I don't know if you've ever seen that movie, but you know it's less Jude Law and more Jason Schwartzman here as being the environmental activist.

The pressures to conform here are really great.

One thing I love about the Bosley Grossman here too is that there is a really powerful sense of mercy.

This book, Everything Flows, could have been written in such a more mean spirited way.

The stories that he shares of the people's lives and why they made the decisions that they did, I feel like he honors them even though he is pointing to their moral frailty.

And I think I can offer that same thing to people who are put in a position of working in these organizations.

I was telling someone about this podcast that I was trying to make.

I've been thinking about the show for a while, like how do I even want to do it?

I was telling someone about it and they told me that an organization was hiring that I, I felt like kind of weird about wanting to work for, but I still had the doubt like, Oh yeah.

I mean, I, I might not be bad to have a job there.

I could probably change things like kind of nudge things on the inside.

It's like even me, I'm like aware of this dynamic.

I feel this.

It's like I care about this a lot.

And even still it's capable of acting even on me.

So how high of a standard should I hold others to if I feel that inside me?

I think this is one of the reasons why I love a mercy based paradigm because if you don't have it, it's so easy to put yourself above everyone else on earth and to think that you are the pure one and you're so much better than everyone else.

But then you'll see something like that and think, wow, actually I am.

You know, with the right opportunity in front of me, I might take that same job that I would have made a podcast against as well.

That's one of the fun things about living long enough to reflect on your life.

So much of what you thought you were better than comes back to you in disguise.

And you realize, wow, I was so judgmental.

I understood little, but I judged much.

And the longer you live, the more of an opportunity I think there is to understand, forgive and focus on the equality amongst people rather than one's own purity.

It's also one of the reasons why I love films like Bicycle Thieves, the Italian neorealist film from the 40s.

Sorry it's going to be spoiled, but this film's again nearly a century old.

It's one of those considered to be one of the best films of all time.

A working class Italian man gets a job predicated on him having a bicycle.

His bicycle gets stolen and he's desperately trying to find his bike and cannot do it and decides to steal someone else's bike.

The film is called Bicycle Thieves.

I didn't really know that much about it before I saw it, but the name of it made me think like, OK, there's going to be more than one bicycle thief.

And the person who stole his bike was singular.

So I imagine he might be put into the position of having to steal a different bike, might be put in a position to do the same.

And even though this man is a family man with integrity and just wants to get his stuff back, is put into a position where he feels like his best option is to steal someone else's bike.

And I think this is just great Christian symbolism about the universality of sin, about how we could find ourselves in these positions.

And so much of how decisions get made are about circumstance and not always about character.

Obviously those things count for a lot too.

And there are even stories inside the vastly Grossman about character and people who made the right decision or more correct decisions than others.

So character does count on the margin.

But some of these things, when you see them enacted at scale, it shouldn't be surprising when you see outcomes that feed the things like bicycle thieves, people taking cushy jobs about changing the world and helping certain companies go net zero, net negative, just buying carbon credits of any kind.

And of course, we somehow seemingly like never get any closer to dealing with climate change before we go deep into overshoot in an attempt to come back and answer this original question of whether or not carbon markets are a club for Saints or a hospital for sinners.

I think that's your call.

Putting it that way leads one to the answer that it's the latter.

I think if you can bring someone into climate action that wasn't already doing climate action, that's in many cases probably on that powerful thing to do.

I think there are versions of it that probably slow down climate action by greenwashing, by giving moral cover to organizations that frankly don't deserve it, while also having mercy for the people in Bosley Grossman's Everything Flows, who don't make the best decisions about how to behave with their time on Earth.

I think if you're still coming back to this podcast hoping for really clear answers, at some point, you should give up on that hope, because I'm not sure that I do either.

I'm trying to grapple with this.

And at the very least, what I might say is I'd like to have a space where some truth telling is possible, where it's not all performative, where it's not all about what's going to lead to the next job, what's going to make sure that my career is secured, my position in society is secured.

You might say, if this was Edwardian England, what a funny way to put it.

But hopefully that makes you think these are the kinds of questions that one's life should have the space to answer.

I'm not telling you what to think.

You can draw your own conclusions.

You are responsible for your actions even though you deserve mercy, your decisions are your own and it's important to think about how to live life given that time here is limited.

Our time to address climate change is limited, and we need to be real.

We need to be asking the serious questions and not only to leave these conversations to the wee hours after the conference we find one another app.

Thanks for listening.

I hope you'll be thinking about it in the days and weeks after this show.

Best